For more than 60 years -- from 1860 until the 1920s -- San Juan County was the principal lime-producing area in the state of Washington. The San Juan Islands were ideal for the manufacture and transport of lime. Large deposits of high-quality limestone were located right on the shoreline with good deep-water harbors protected from prevailing winds. Largely by gravity, quarried limestone was shunted downhill to the top of kilns, fired with high-temperature-producing old-growth Douglas fir, and then drawn out from the bottom of the kilns as lime. Packed in barrels, the final product was transferred to warehouses built on or close to wharves. Fleets of ships, both sail and steam, regularly transported the lime to Puget Sound, West Coast, and Pacific Rim markets, where it was in demand as a building-construction material and as an important ingredient for several growing regional industries, including smelting and papermaking.

Valuable Deposits

Used for centuries as the main mortar for masonry buildings and as a plaster covering for walls, lime (CaO) is produced from limestone, a sedimentary rock composed primarily of the mineral calcite, or calcium carbonate (CaCO3). San Juan County limestone beds used in the quarry industry date from two periods. The older are the 246-to-248-million-year-old limestone layers at Lime Kiln Point State Park, known geologically as the Deadman Bay Volcanics. The beds at Roche Harbor, known as the Orcas Chert, date from around 200 million years ago, though there is some controversy as to when exactly they formed. Both rock units consist of basalt inter-fingered by thin beds, or lenses, of limestone, which is what is quarried. A modern analogy to how these ancient rocks formed is the seamount/atoll system of the tropical Pacific, where lava erupts, cools in the ocean, and tumbles down deep into the water, where it is covered by limey mud and reef invertebrates, which eventually becomes limestone.

Neither layer formed near its present location. Both are part of what is known as the Deadman Bay Terrane. (A terrane is a discrete fault-bounded layer of rock that typically formed in one location and was transported by tectonic movement to another.) Eastward movement of the Farallon Plate carried the basalts and limestones of the Deadman Bay Terrane and attached, or accreted, them to the North American Plate between 84 and 100 million years ago. Evidence for this comes from fossils in the limestones, in particular, single-celled invertebrates known as fusulinids only found in place in rocks around Japan.

Limestone is found in the older rocks forming the central portion of the San Juan archipelago. This forms a belt extending from the northeastern portion of Orcas across that island to the northern and western portions of San Juan, and includes the smaller islands in between such as Crane, Jones, and Shaw. The U.S. North West Boundary Survey first discovered and tested limestone on the west and north side of San Juan Island in 1859:

"The value of these discoveries can better be appreciated from the fact that up to the time of the discovery of limestone on this island it was not known to exist at any point on Puget Sound, within United States territory, and for building purposes it was necessary to procure all the lime used, from California or Vancouver's Island" ("Geographical Memoir").

Quarrying and processing lime began on San Juan when the British Royal Marines occupied the north end of the island as part of the 1859 agreement between the United States and Great Britain to jointly occupy the disputed islands until the resolution of the territorial dispute known as the Pig War. They used the lime for paint, whitewash, and mortar in the construction of their buildings.

Early Lime Companies

The next year Lyman Cutlar (d. 1874), whose shooting of a Hudson's Bay Company pig had touched off the Pig War standoff, partnered with E. C. Gillette and Frank Newsome to produce lime on the west side of San Juan near Deadman Bay where Lime Kiln Point State Park would be established more than a century later. Gillette sold his interest to Augustin Hibbard (d. 1869) after the first winter of operation, and the new trio formed the San Juan Lime Company in 1861. Eureka, located north of Friday Harbor on the east coast of San Juan, was founded around this time by an Englishman named Roberts; it was later owned and operated by Daniel and William McLachlan and their cousin by marriage, Thomas Lee. Port Langdon, on the east shore of Orcas Island's East Sound, was first quarried in 1862 by George R. Shotter; in 1874 it was sold to Daniel McLaughlin and Robert Caines.

At the San Juan Lime Company, Hibbard bought out Cutlar and Newsome at the end of 1864, and continued operations until the following year, when George R. Shotter and Company bought in. In 1868 Hibbard borrowed $1,500 for operations from Catherine McCurdy of Port Townsend, secured through a mortgage on the land, and bought out Shotter. A year later, he formed a partnership with Nicholas C. Bailey, Charles Huntington, and Charles Watts. This agreement was shattered three months later, when Watts murdered Hibbard. Court-appointed appraisers prepared inventories of the property, and the heirs petitioned for distribution of the estate in 1871; the court eventually ordered the sale of the property to cover numerous debts and the mortgage held by Catherine McCurdy.

The property was sold in 1873 to none other than Catherine McCurdy for $1,500. She turned it over to her son, James, to operate with former San Juan Lime Company partner N. C. Bailey. Within a few years, they had expanded production to 20,000 barrels per year. Then Bailey died, leaving his half of the company and property to his wife, Jane, and their two children. Within a few years, Jane Bailey married James McCurdy, thus uniting their ownership of the operations as "McCurdy's."

A review of the 1870 and 1880 federal censuses gives a general sense of early lime production in the islands, as well as the typical business operations of these small kilns. As recorded in the 1870 federal census, the San Juan Lime Company produced $26,000 worth of lime -- 13,000 barrels -- and employed 18 men for six months of a year for a total payroll of $11,000. Port Langdon, listed as "Shotwell & Company," had $7,000 in capital, 25 employees ($2,000 in wages), and produced 8,000 barrels in six months, for a value of $16,000 at the going rate of $2/barrel. By the time of the 1880 census, McCurdy's was producing only $18,000 of lime, and paid $6,000 to the 21 employees who worked there nine months of the year. The typical work day was 10 hours, 9 in the winter; a day's wage for an "average day laborer" was 75 cents, but a "skilled mechanic" could earn as much as $3.50.

Most of the product during this period went to regional cities and towns: Victoria, 14 miles west across Haro Strait on the southern tip of Vancouver Island, and Puget Sound ports such as Port Townsend, Seattle, and Tacoma. According to an 1878 newspaper article, of the 8,000 barrels produced through August of that year, two-thirds had been shipped to Tacoma and thence to Portland via railroad, while another 1,000 had been sent to other Puget Sound ports and to British Columbia.

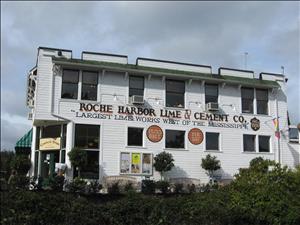

In 1879, Robert and Richard Scurr bought property at Roche Harbor on the north end of San Juan Island and, in conjunction with brothers Alexander, Colin, and Donald Ross, developed two kilns. John S. McMillin (1855-1936) bought the property and works in 1886 from the Scurr and Ross brothers, establishing the Tacoma and Roche Harbor Lime Company. During the early 1880s, McCurdy's operation at Lime Kiln on the west side of San Juan began to slip. Production dropped to 7,000 barrels per year and McCurdy began borrowing heavily from several sources.

McCurdy's mother sold her latest promissory note and mortgage to McMillin, who then leased the property from James and Jane McCurdy for three years, beginning in September 1886. One month later, the McCurdys sold their property to Henry Cowell (1819-1903) of San Francisco. Cowell refused to pay the mortgages on the property, forcing foreclosure by the Tacoma and Roche Harbor Lime Company; he then picked up the property at the subsequent bankruptcy sale. McMillin responded by filing suit against Cowell and others, claiming that they were depleting the resources on land leased to McMillin. In this, the first of several legal battles between McMillin and Cowell, the judge eventually found for the defendants and dismissed the case.

Economics of the Lime Industry

The production of lime in the San Juan Islands reflects the economic development of the Puget Sound region, as well as trade with California and Hawaii. Puget Sound cities such as Bellingham, Everett, Seattle, and Tacoma witnessed extraordinary economic growth after the arrival of transcontinental railroads. The railroad spurred development of industries such as mining, smelting, and papermaking, which in turn fueled the lime industry in the San Juan Islands. However, the Panic of 1893 soon dragged the local economy into another depression, from which it did not recover until the stimulus of the Klondike (Yukon) Gold Rush of 1897. Another boom period followed until the Depression of 1907. These economic booms and busts contributed to the formation, rise, and decline of many small companies of one or at most two kilns. Eventually, the economics of the lime industry led to the gradual consolidation and aggrandizement of these smaller operations into ownership by either Cowell or McMillin.

James McCurdy together with Nathan Gregg and J. C. Brittain filed for incorporation of the McCurdy Lime Company, headquartered in Eastsound, in July of 1888. But by September Gregg and his wife Maggie had filed suit against the others for not fulfilling their investment. What subsequently became known as "Gregg's Lime Kiln" lasted only a few years. Nearby, an 1892 map indicates operations run by the Bowen Bros. & Jamieson and Dailey & Boyd. Port Langdon, on the east shore of East Sound, also passed through the hands of several owners. On the west side of Orcas, at least two small operations flourished for a brief period: the Eagle Lime Company (1900-ca. 1910) and the Island Lime Company (1900-ca.1907).

Lime was used in several budding Puget Sound industries. Quicklime was used as a flux in smelting steel and other metals to remove impurities. The Port Langdon quarry was reworked in 1898 to provide rock for the Tacoma Smelter. Begun in 1888 as a lead smelter, the Tacoma Smelting and Refining Company reorganized under William Rust (1850-1928) in 1890, eventually becoming the largest on the Pacific Coast. In 1905 Rust sold the Tacoma property to the American Smelting and Refining Corporation (ASARCO), which turned it into a copper smelting and refining plant. In Everett, a smelter had been built by Rockefeller interests as part of the Great Northern Railway's development of the city as the "Pittsburg of the West." In 1903, this smelter was also sold to ASARCO, which operated the facility intermittently until 1912.

"Paper rock" was used for processing pulp (cellulose) in the papermaking process. Several pulp mills were established in the Puget Sound region; one of the earliest was the Puget Sound Pulp and Paper Company mill, constructed in 1889 in Lowell (Everett). This was joined by the Soundview (1931) and Weyerhaeuser Mill A (1936) to form the 'Big Three' pulp and paper producers in the city. To the south, the Crescent Boxboard Company, which began operations in Port Angeles in 1919, was joined a year later by the Zellerbach Company's Washington Pulp and Paper Corporation (later to become Crown Zellerbach). To the north, in Bellingham, the Puget Sound Pulp and Timber Company was assembled from pulp and timber companies throughout the Puget Sound; during the Depression the plant was sold to Soundview Paper Company. In the 1950s and 1960s, several of these companies merged into larger corporations such as Scott Paper, Crown Zellerbach, and Georgia Pacific. All of them used San Juan County lime or limestone.

Hawaiian plantations used San Juan County lime as 'sugar rock' in the refining process. Lime was also used as a source of fertilizer in the sugar cane fields. Ships bearing barrels of lime for the sugar plantations sailed from the San Juans to Hawaii on a regular basis.

Work and Life at the Lime Kilns

Quarrying, firing, and barreling lime was hard and dangerous work. "Powdermen" blew the limestone free from the cliffs with explosives and then "breakers" split the larger boulders. Men who "broke rock" were described as solidly built with sinewy arms, able to wield jackhammers skillfully and repeatedly, knowing where the fissures were and how to strike them just right so as to split the rocks into the right size pieces (usually eight to 12 inches in diameter). One twentieth-century innovation was the compressed air (pneumatic) drill, which was used to drill holes for the explosive charges, as well as to break up the large boulders. Then workers had to haul the rock to the top of the kilns, which involved either leading a team pulling carts on rails or sending the ore in buckets down a funicular. The quarried limestone could either be shipped unprocessed or burned in the kilns to produce lime. It was heavy, loud, and dusty work that required a great deal of strength and endurance.

Wood -- principally old-growth Douglas fir -- was the fuel used to "burn" limestone. Cut into four-foot long split logs called cordwood, it took about three to four cords to fire a kiln continuously through a 24-hour period. Wood was supplied by woodcutters and farmers clearing their land on Lopez, Orcas, and San Juan, as well as many of the nearby smaller islands, and hauled by wagon or shipped by scow to the kiln sites. Every kiln operation had several wood cutters who provided fuel for the kilns. Wood cutters made from $1.50 to $1.75 per cord, and a good woodman could cut 1.5 cords a day.

Quarrymen loaded the stone -- about 15 tons at a time -- into the top of the kiln, while firemen, working twelve-hour shifts, fired the kiln and maintained the proper temperature, keeping it hot but not too hot. The wood did not come into contact with the limestone; hot air passed upward through the stones, driving off the carbon dioxide (CO2) from the calcite (CaCO3) to form lime (CaO). It was about 24 hours from the time lime passed the firebox to when it was drawn from the bottom of the kiln. Workers drew about every three or four hours, with the average draw being 12 to 15 barrels.

The "burnt" rock, which was still in large chunks (six to eight inches in diameter), was raked out of the bottom part of the kilns by means of long (10-to 20-foot) rods and channeled into a chute. From there it would be packed in barrels and the heads sealed in order to keep the lime from hydrating once again. Barrels were usually assembled at a cooperage located within easy distance of the kilns, so that they would be ready at hand for packing. The barrels, weighing between 200 and 250 pounds each, were then put on a funicular or loaded on a flatbed wagon that was drawn by horses along tracks to warehouses near the wharf, where they could be stored until shipped to market. Workers took great pride in being able to stack the heavy barrels three layers high.

The men who did all these jobs were of mixed ethnicity and nationality. Industrialists took advantage of the various immigrant groups that came to America for work, so the limekiln populations changed over time. Early on, the majority of workers were English, including a strong contingent of quarrymen from Cornwall; Irish; or Welsh, with a few Chinese working as cooks. In the 1890s and early 1900s, many Japanese worked at Roche Harbor. However, by 1910 the nationalities of the workers had shifted: census takers enumerated many "Austrians" -- actually from Croatia, part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire at the time -- at Lime Kiln, and Scandinavians and Russians at Roche Harbor.

Because most lime kilns were located in areas that were not near other settlements in the islands, companies often provided housing and meals for the men working there. The boarding house at the San Juan Lime Company works at Lime Kiln was typical: a large, two-story frame building that included a kitchen, dining hall, store, and superintendent's residence downstairs and bunk rooms upstairs. Several limekiln operations served as community centers by providing stores for supplies and post offices for mail. Eureka on the east shore of San Juan had a post office, named Werner, for the brief period from 1890 to 1892, as well as a hotel, saloon, two bunkhouses, and several cabins. Roche Harbor became a small village, including residences for the McMillin family as well as management and workers, a hotel, store, church, school, and doctor's office. Lime operations were at the forefront in adopting technological innovations such as electrical power and telephone systems.

Depression and Decline

Except for Roche Harbor, the kilns at most limestone operations in San Juan County were shut down permanently in the 1930s. The kilns' closure coincided with the Great Depression, when the demand for lime declined severely. Also contributing to the closing of the lime works was antiquated or outdated technology. Since the processing of lime in San Juan County had not changed significantly in almost 60 years, it was inefficient, labor-intensive, and therefore not cost-effective to continue operations. Moreover, the deposits of high-quality limestone located in the quarries near most of the kilns had been exhausted. The lower-grade rock was too far away from the kilns, requiring more labor and materials to haul it to the kilns.

Shipping costs rose, and fewer ships sailed the waters of Puget Sound. Freight bound for West Coast cities was primarily being sent by rail. There was some market for agricultural lime in Eastern Washington, which meant it was packaged in sacks and hauled by barge or scows to Everett, where it could easily be transferred to rail cars. The remaining lime was destined for pulp mills in Puget Sound. Lime manufacture continued until the onset of the Depression, reaching a nadir in 1933. During the 1940s and early 1950s, production gradually shifted to paper rock. Operations lasted the longest at Roche Harbor, continuing until 1956, when the property was bought and converted it into a resort.

By the time geologist Wilbert R. Danner surveyed kiln and quarry sites in San Juan County for his Limestone Resources of Western Washington (printed in 1966, with field work conducted in 1959-1960), none were actively producing lime and only a handful were being quarried, mostly for paper rock. On San Juan, 10 quarries were identified, but none of them were operational; on Orcas, of the thirty or so known quarries only three had been active during the recent past; and the scattering of quarries on Cliff, Crane, Henry, and Shaw islands had ceased operations decades before. What remains is a legacy of the extensive lime industry that was so vital to the economy of the San Juan Islands and the Pacific Northwest.