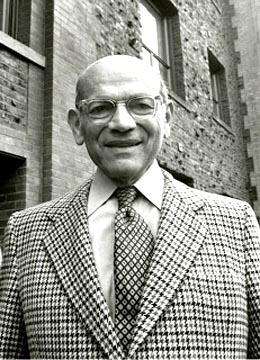

Jesse Epstein was the primary force behind the creation of the Seattle Housing Authority and was just 29 years old when he was appointed its first director in 1939. He was working for the University of Washington's Bureau of Governmental Research when the federal Housing Act of 1937, which subsidized the construction of low-income housing, was passed. It presented a huge opportunity, and Epstein took full advantage. He shepherded the necessary enabling laws through the 1939 legislature, then took the leadership of the Seattle Housing Authority in April that year. Seattle's first low-income-housing project, Yesler Terrace, used $3 million in federal funds and was, at Epstein's insistence, well built, of appealing design, and racially integrated. During World War II, all federal housing funds went for defense workers and military families, but in Seattle several such projects were later converted to low-income use. Epstein led the SHA until 1945, and by 1947 was the Federal Housing Authority's regional director for nine Western states. He was briefly tainted during the anti-communist hysteria of the post-war 1940s, left government to return to academia, and then practiced law in Seattle. He remained involved in civic affairs until his death in 1989.

Born in the USA?

Jesse Epstein (there is no evidence of a middle name) told an interviewer in 1973 that he was born in Great Falls, Montana, but other sources put his birthplace in Russia, and the 1930 U.S. Census named Poland. On balance, it seems most likely that he was born on July 18, 1910, (some sources say 1911) in what is today Poland, but was at that time ruled by the Russian tsar. According to census records, Jesse's first language was Yiddish, although he surely mastered English at an early age.

His parents, Joseph H. Epstein (1876-1945) and Bertha Epstein (1880-1950), moved to American in 1912 with 2-year-old Jesse and his older sister, Rosie, born in 1908. They settled in Great Falls, where Joseph opened a second-hand store. Two more daughters, Esther and Lillian, were born there in 1913 and 1916, respectively.

There is little information about Jesse Epstein's early childhood in Montana, but by his teen years he was demonstrating an interest in civics and skill at debate. By 1927, his senior year, he was a respected leader among his peers. Under the motto "My mind to me a kingdom is," yearbook editors wrote of him: "Among the gems in our class there is one who can stand alone -- Jesse Epstein. He is an excellent student, a prominent speaker, and a talented essayist" (The Roundup, 1927). Among other listed activities, he was in the Honor Society, president of the Student Council, president of the senate debate team, and president of the Business Club.

The Great Depression and the New Deal

Epstein entered the University of Washington as a freshman in the fall of 1927. It was the year Charles Lindbergh (1902-1974) made the first solo flight across the Atlantic and the year of the first transatlantic telephone call; the year the first full talkie, The Jazz Singer, was released and the year Henry Ford retired the Model T and introduced the Model A. It was the era of the flapper, speakeasies, and bathtub gin, a frenetic time that concealed from most the early signs of an impending, worldwide economic disaster.

Epstein majored in political science and soon picked up where he had left off at Great Falls High School. Although the record is sparse, a local newspaper reported in May 1928 that he was named president of the university's Badger Debate Club, one of five (three for men, two for women) that debated among themselves and with teams from other schools. In the 1920s, formal student debates were a major campus attraction and filled the main floor of the university's Meany Hall when teams from other universities came calling.

Then, in the early weeks of Epstein's junior year, came the catastrophe that darkened the future of the United States along with most of the industrialized world. America had endured economic meltdowns before, but this one, unprecedented and as yet unequalled, would forever be known as the Great Depression, and it gripped almost the entire globe. For more than three agonizing years after the New York Stock Exchange collapsed on Black Tuesday, October 29, 1929, the U.S. government seemed paralyzed, unable to reverse or even slow the nation's descent into a chasm of closed factories, failed banks, and crippling unemployment. Human misery was widespread, exacerbated by the man-made ecological catastrophe known as the Dust Bowl. It was a crisis of faith as much as finance, bringing into question whether a democratic government dedicated to a free-market economy could adequately feed, clothe, and house its citizens.

Epstein earned his bachelor's degree and in 1932 enrolled in the university's law school. Later that year, Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882-1945), a Democrat, was elected president, winning 42 of the 48 states. In the closing words of his speech accepting his party's nomination in July 1932, Roosevelt had promised "a new deal for the American people" ("Address Accepting ..."), giving name to what would become the most aggressive and pervasive intervention by the federal government into the economic life of the nation since its founding.

Soon after his inauguration in March 1933, Roosevelt won passage from a largely compliant Congress of a panoply of remedial programs that would be modified and supplemented as conditions demanded. These forever changed the role the federal government would play in securing the necessities of life for its citizens, and they dovetailed nicely with Epstein's idealism and aspirations.

The Bureau of Governmental Research

Epstein may have been inspired by Roosevelt's words, but he had his education to complete, and at that he continued to excel. In 1933 he was one of two UW men invited to take the final qualifying exam for a prestigious Rhodes scholarship, and although neither was selected, just being in the final grouping was a significant academic honor.

Epstein received his law degree in 1935 and went to work as a teaching fellow and research assistant for the Bureau of Governmental Research, housed in the university's political-science department. The bureau had opened on July 1, 1934, as the research arm of the Association of Washington Cities, a private, nonprofit corporation established just a year earlier to coordinate the activities of and provide a variety of services to local governments throughout the state. (The Bureau of Governmental Research was later renamed the Municipal Research and Services Center [MRSC].)

One of Epstein's jobs was to comb through congressional enactments, presidential orders, and federal regulations in search of policies and programs that could help Washington's counties, cities, and towns pull themselves out of the morass of the Depression. It must have been tedious, mind-numbing work at times, but the stakes were high; only the federal government had demonstrated the means, the moral authority, and the regulatory might to slow the economic decline.

In 1937, Epstein found what he was looking for, a cause that would engage him for more than a decade and change the face of Seattle. In September of that year, Congress passed the Housing Act of 1937, also known as the Wagner-Steagall Act, the first law in the nation's history to provide federal funds directly to local governments for the construction of low-income housing. The law was laden with politically necessary declarations about reducing unemployment and stimulating business activity, but its fundamental goal was to get the federal government deeply involved in providing affordable housing for low-income Americans. A United States Housing Authority was established in the Interior Department, funded initially with $500 million. Local governments that committed to building public housing were eligible for low-interest loans equal to 90 percent of project costs and given up to 60 years for repayment on very generous terms.

It was just the sort of program Epstein had been looking for, but he couldn't move on it at once. The Housing Act required the existence of local housing authorities to administer the federal funds. These could not be established in Washington without a grant of power from the state legislature, which then met only on odd-numbered years. It had adjourned the 1937 session months earlier, and any attempt to get the necessary laws enacted would have to wait until early 1939. This turned out to be a good thing.

Lining Up the Locals

By 1937, much of the nation's economy, including that of Washington state, had started to recover, due almost entirely to federal interventions and programs. There was a brief recession that year when the Roosevelt administration tightened the purse strings in an attempt to balance the budget, but renewed spending soon brought things back on track. Now heated political debates about the proper role of government, which had quieted somewhat during the most desperate years, were rekindled. Many believed that the Housing Act of 1937 and similar laws were simply socialism disguised, and not very well disguised at that.

Epstein had a selling job to do, and all his training in debate and oratory would come in very handy. His credibility was enhanced with an appointment in March 1938 to a panel of "relief judges" whose job it was to "to review all federal works activities in the state and judge their comparative values to the communities in which they were performed, or are being performed" ("Works Judges Are Named"). At almost precisely the same time, Seattle Mayor John Dore (1881-1938), who was in perilous health, decamped to Arizona and was briefly replaced by Acting Mayor James Scavotto (1910-1990), the city council president.

First, Epstein had to demonstrate that Washington cities and towns had the political will to act. He quickly persuaded Scavotto to establish a seven-member "civic committee to make plans for a federal-aid housing program." Epstein represented the Association of Washington Cities; other members represented architects, realtors, other interested groups, and the city's Federation of Women's Clubs, always active in social-welfare work. The members were to survey Seattle's housing needs and determine how best to "take advantage of the Wagner-Stegall [sic] Low-Cost Housing Act if the State Legislature passes an enabling act" ("Five Named to Housing Board"). The all-volunteer group was called the City Advisory Housing Commission and later was given $25,000 with which to do its job.

Mayor Dore died on April 18, 1938, having been replaced permanently five days earlier by Arthur B. Langlie (1900-1966), a city councilman who had won the March mayoral election and was appointed by the council to fill the remainder of Dore's term before starting his own. Langlie was a different political animal than Scavotto, much more conservative, a foe of government spending (he had run on a pledge to cut city taxes by 40 percent), and a harder sell for Epstein's plans. But by stressing the slum-clearance and job-creation benefits of public housing, Epstein was able to win Langlie's necessary, if wary, support. It helped that the day before Dore's death, Washington Governor Clarence D. Martin (1884-1955) announced a meeting with the head of the U.S. Housing Authority in Washington, D.C., and in a telegram to Epstein pledged "full cooperation in housing legislation at the next session of the legislature" ("Martin to See Housing Chief").

With the city and state chief executives on board, it was the city council's turn, and on April 20, 1938, the council unanimously adopted a resolution pledging to create a Seattle Housing Authority once the state legislature granted the necessary powers. The resolution also asked the federal government to earmark money for Seattle despite the fact that the city still had no legislative authority to proceed. (Washington would be the 35th state to draw on the federal housing funds, and there was fear the pot would be empty by the time the legislature next met, in January 1939.)

Tackling Olympia

State legislators held a wider range of political views than did Seattle's elected officials, and some were deeply hostile to anything that smacked of government interference in free enterprise. To secure passage of the needed legislation, Epstein toured the state, persuading many doubters that having government finance the building of low-income housing would not endanger the private sector, but would in fact create for it new and lucrative opportunities. In between speaking engagements, he met with cooperating legislators of both parties to help draft the necessary enabling acts. They smoothed out as many philosophical differences as possible, but success was by no means assured. Two housing bills were in the legislative hopper: the Housing Authorities Law and the Housing Cooperation Law. Together, they would empower local governments to create local housing authorities and grant them the powers necessary to do their jobs.

The 1939 session of the Washington State Legislature began on January 9, and two days later Governor Martin urged passage in his official message to lawmakers, pointing out that "while we do not have the slum problems of the older cities ... it may be possible to adopt this federal plan to the housing needs of some of our communities" ("Text of Governor's Message ... ."). State senators, more liberal than their House counterparts, passed the two bills on February 2, 1939, by handy margins. The senate bills then became bottled up in the rules committee of the House of Representatives. Strong conservatives held a majority there, but King County Democratic Representative Michael King shook things up when he made a motion to strip the rules committee "of further responsibility in the consideration" of the two housing bills ("House Liberals Plan New Fight"). His motion was soundly defeated by the full House on February 21, but the Democrats picked up more votes than expected. It also helped that the legislature was at the same time considering increases in the very-popular old-age-assistance programs. The two housing bills managed to squeak through the House the next day and became law on February 24, 1939, when Governor Martin signed them.

Meanwhile, Back in Seattle . . .

Much had been going on in Seattle while waiting for the legislature to act. The commission appointed by Acting Mayor Scavotto the previous year had operated on the optimistic assumption that the housing bills would pass, and it had already completed its survey of the city's housing needs by the time they did. Speaking before the Seattle Realty Board on November 17, 1938, Epstein reported that the survey had found that 28 percent of Seattle's residents paid less than $15 a month in rent, and several thousand city residential units did "not meet adequate-housing standards" ("Public Housing Plans Outlined"). More than 17,000 dwelling units in the city lacked baths or private toilets. In a speech given to a group of educational workers on December 22, he went straight at a main argument of his opponents:

"Some deny, of course, that we have slums in Seattle, but a survey has disclosed that there are many sub-standard houses. That is to say, thousands of homes, found in this survey, are unfit for human habitation. The reason they are unfit lies in the menace to health, susceptibility to disease and in lower moral standards" ("Slum Clearance Bill Forecast").

Seattle wasted little time once the go-ahead was received from Olympia. On March 13, 1939, three weeks after the housing bills became law, the Seattle City Council created the Seattle Housing Authority. One week later, Mayor Langlie appointed an unpaid board of commissioners to direct the new agency: George W. Coplen, a builder and developer; Charles W. Doyle (1874-1958), secretary of the Seattle Central Labor Council; Metta Henderson (1892-1976), from the Seattle Federation of Women's Clubs; Kenneth J. Morford (1897-1961), a mortgage broker; and, as chairman, Jesse Epstein.

Just seven weeks after the legislature had passed the necessary laws and 30 days after the SHA had been created, a $3 million federal loan was announced on April 13, 1939. Epstein, just 29 years old, stepped down as chairman of the SHA and was appointed executive director, a salaried position.

Yesler Terrace

For its first project, the Seattle Housing Authority had selected 43.5 acres just east of downtown at the southern end of First Hill in an area then called Yesler Hill. A thousand people lived there in 471 separate dwelling units, fewer than 5 percent owner-occupied, almost all ramshackle. The few once-grand Victorian homes dating from the city's earlier days had been chopped up into ratty boarding houses; most of the later-built duplexes and row houses were left unmaintained and unimproved by absentee landlords. But there were good things about the site, too -- it was close to King County's public hospital and several schools, an easy walk from downtown, and blessed with magnificent views that it was hoped would help give future residents "pride of place" (Sale, 165).

Low-income families of a wide range of backgrounds -- whites, African Americans, Chinese, Japanese, Filipinos, along with "a smattering of Indians, Greeks, and Eskimos" as a report put it at the time (Miller, 1) -- lived in the old buildings, and all had to be relocated. Existing residents were given priority in the new development, but only households headed by U.S. citizens and able to meet strict financial-need requirements (no more than $1,200 annual income) would be eligible. And housing in what would be called Yesler Terrace was specifically limited to families; unmarried men and women were excluded.

Early in the process, Epstein made two very important and almost entirely unilateral decisions, one based on aesthetics, the other on his notion of simple justice. The first was a rejection of the U.S. Housing Authority's sample plans, which were intended to expedite the design process and limit construction costs but suffered from a drab, unimaginative sameness. Epstein instead hired a team of five local architects -- William Aitken (1889-1971), William J. Bain (1896-1985), John T. Jacobsen (1903-1998), J. Lister Holmes (1891-1986), and George W. Stoddard (1896-1967) -- to plan the project and the dwellings within it.

Epstein's second decision was, for its time, daring and controversial -- Yesler Terrace would be fully integrated; eligibility standards would be applied without regard to race. It may well have been the first integrated public-housing development in America. Certainly, many other such projects around the nation were strictly segregated, and the federal government neither required nor forbade integration. But Epstein believed that the right of all citizens to benefit equally from government-funded low-income housing was self-evident and debate unnecessary. As he explained in a 1973 interview:

"So far as racial composition or considerations were concerned, I made the decision administratively, early, that there would be no discrimination, no segregations, and, to me, that particular approach or way of handling the matter was so obvious that I did not ask the board to declare a policy in writing. I felt that it could be handled administratively and I was also a little concerned that if I raised the question there might be some consideration given to such matters as quotas, maybe even segregation" (Epstein interview).

With these decisions made, Epstein tended to a personal matter. On December 5, 1940, he married Sylvia Wolff (1905-1992) in Grays Harbor. They would remain together until his death in 1989.

On February 28, 1941, the Seattle Housing Authority signed a contract with the J. C. Boespflug Construction Company of Montana to build a total of 690 dwelling units at a price of $2,176,000. Construction began in April 1941 and was completed in little more than a year. Victor Steinbrueck (1911-1985), noted Seattle architect and preservationist, later described what the tenants found when they moved in:

"Each family unit has its own private sitting-out area and yard and is afforded a view by the terrace site planning and flat shed roofs. The design and color of the well-arranged buildings ... make this good contemporary architecture. Only in such a public project has it been possible to provide play areas and community social and recreational facilities giving a most complete environment" (Seattle Cityscape, 159).

Sidetracked by War

When the Seattle Housing Authority received the funding for Yesler Terrace in April 1939, it could not foresee that providing places to live for low-income families would soon no longer be even a small part of its mission. But in June 1940, with American industry arming Britain and eventual U.S combat involvement no longer unthinkable, Congress amended the Housing Act of 1937. Henceforth, any federal low-income housing money allocated but not yet spent was to be used to build accommodations for defense workers and military families.

Just a few months later, in October 1940, Congress passed the Lanham Act, which completed the redirection of money from the needy to the needs of war. Seattle was a major center for defense industries -- Boeing, Issacson Steel, and Todd Shipyards, to mention just three -- and the city was laboring under a severe housing shortage. Just one week before Pearl Harbor, The Seattle Times (a consistent critic of expenditures for low-income housing) acknowledged the crisis:

"Auto and trailer camps, jammed to overflowing and with their 'no vacancy' signs out; newcomers actually sleeping in automobile garages, not knowing where to look for better shelter; dark, windowless attics of old houses, crammed with ten or twenty defense workers' cots, or as many as they will hold" ("City Housing Shortage... ").

After such an auspicious start, Jesse Epstein now had to turn his attention away from those in want. He must have been disappointed by the interruption, but he carried out his new responsibilities with the same skill and drive that had led to the creation of Yesler Terrace.

Rainier Vista, Holly Park, High Point, and More

On July 4, 1941, Epstein announced that the Seattle Housing Authority had been selected to build and manage Rainier Vista, a $1,750,000 housing development for defense workers on city-owned land at the north end of Rainier Valley. Seattle architect B. Marcus Priteca (1889-1971) and architect/engineer A. M. Young (1884-1954) were hired to design 500 housing units in 231 one-story buildings on 90 acres. Construction was completed in less than a year.

About a mile and a half south, on the eastern slope of Beacon Hill, a second defense-housing development, considerably larger, was soon underway. This project, Holly Park, opened 300 housing units in September 1942, and when completed nearly a year later covered 108 acres with 339 one- and two-story duplexes and four-plexes -- 900 total living units.

By the time the United States entered World War II as a combatant in December 1941, the Seattle Housing Authority was building housing at a furious pace. In January 1942 a 178-unit expansion of Yesler Terrace was funded to house defense workers. In West Seattle, construction on High Point was underway, planned for 950 units, the largest SHA development yet. The paint was not yet dry there when an adjacent 37 acres was condemned for an additional 350 units. Additions were being made to other developments as well, and by the end of 1942 the Seattle Housing Authority had completed or was nearing completion on 3,768 housing units. All but the original 690 in Yesler Terrace were reserved for defense-industry workers and military families.

It was not nearly enough. The housing authority responded as best it could, building temporary accommodations that included 700 units at the Duwamish Bend Development, a 122-unit expansion at Rainier Vista, a 100-unit addition at Holly Park; a new 40-unit development on Minor Avenue; 450 units at Delridge (in West Seattle); and 416 units in a project called Stadium Homes near Sicks' Stadium. By the end of the war in 1945, the Seattle Housing Authority was managing more than 8,400 units of housing, most of them meant to be temporary.

Race, Again

In the northern states, at least, poor people of all colors had often lived in close proximity to each other, but the same was not true of the nation's Depression-depleted middle class, from which many defense workers and military personnel were drawn. Racism, which Epstein had so quietly outmaneuvered at Yesler Terrace, reared its head again in the wartime housing developments. As he would later recall, race did not become a major problem

"until we built other projects, especially in areas that had never been mixed, such as West Seattle, Holly Park, Rainier Vista, and Sand Point Homes. The pressure on me was terrific ... . I had many meetings, many pressure groups, many phone calls, some threats ...." (Epstein Interview).

A potential flashpoint was the temporary, dormitory-type housing for single people. The defense industries that were drawing thousands to the city feared that racial unrest would disrupt production, and criticized Epstein in Washington, D.C., for using defense housing for "social experimentation" (Epstein Interview). Even Boeing pushed strongly for segregated housing, telling Epstein that without it, the company would have trouble recruiting workers from the Southern states.

Epstein was more than willing to play his part in the war effort, but he was not willing to surrender on basic questions of equality. When the first integrated dormitories were about to open, he was asked to provide extra police protection. He refused. When extra police showed up anyway, he contacted city officials and had them withdrawn. It was a gamble, but a largely successful one, as Epstein later noted:

"This is not to say that there were not incidents in the dormitories, there were. But ... I think I can say in all cases where there were flare-ups, they were the flare-ups that might occur in any dormitory, and really did not have, so far as I was aware, any racial overtones ... . As is so often the case, these fears were more in anticipation than in reality. As soon as the people moved in, things seemed to go very well" (Epstein Interview).

Moving On

By June 1945 Germany was defeated, the greatly diminished Empire of Japan was on the ropes, and both Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal had passed from the scene. The end of the war was in sight, and plans were being made to convert much of the defense housing built in Seattle and elsewhere to low-income use once peace finally came. It was a process would end up taking nearly a decade.

Jesse Epstein would play little further role in the operation of the Seattle Housing Authority. It was an agency he brought into existence almost single-handedly, nurtured through its crucial first years, and impressed with an ethos of racial equality that was not at the time widely shared. On June 2, 1945, he was named regional director of the Federal Housing Authority in Seattle, and replaced at the Seattle Housing Authority by Charles W. Ross (1903-1982), who would ably lead the organization for the next 23 years. Epstein was soon promoted in the federal ranks, and in August 1947 was named the FHA 's West Coast director. His jurisdiction now covered nine Western states and was administered from San Francisco, so he and Sylvia moved there.

Epstein would deal with many of the same issues in his new post, but lacked the near-absolute authority he had wielded as head of the Seattle Housing Authority. One troubling and seemingly intractable problem was the de facto segregation that had developed in many wartime housing projects, even some in Seattle. He found that this problem was almost impossible to eradicate without strong backing from his superiors in Washington, D.C., and that backing was not forthcoming. In Seattle, Mayor William F. Devin (1898-1982) had formed a Civic Unity Committee in 1944 to address growing fears of racial violence that surfaced as the calming effects of wartime solidarity began to dissipate. Most cities under Epstein's jurisdiction made no such efforts. Questions of race, which he believed should not even be an issue in public housing, continued to bedevil him, and he did not have the tools or support to do what he thought necessary to address them. He did his best, but it was not the most fulfilling work of his life, and his higher visibility would eventually bring him unwanted and undeserved attention.

The Red Scare

In 1948 there came a new challenge, a very personal one. After the war, fear of the Soviet Union and Communism flared up anew in America, and unscrupulous politicians at all levels were building careers on fanning the flames, holding raucous hearings around the country, searching every nook and cranny of government and academia for alleged "Reds" and "fellow travelers." Whispers often were enough to convict in the public mind. In Washington state, the witch-hunt took the guise of a Joint Fact Finding Committee on Un-American Activities, established by the legislature and headed by Spokane Republican Representative Albert F. Canwell (1907-2002). In July 1948, the committee heard testimony in Seattle while trying to ferret out faculty members at the University of Washington who had, or were rumored to have had, any connection to a vast catalog of suspect organizations and people.

One of the star witnesses for the committee was UW English Professor Sophus K. Winther (1893-1983), a lapsed and repentant Communist Party member. While he was being questioned by the committee's lead investigator, William J. Houston, the following exchange took place, which referred to events that supposedly occurred in 1935:

"MR. HOUSTON: Now, do you -- did you know a young man by the name of Jesse Epstein?

"DR. WINTHER: Yes, I did.

"MR. HOUSTON: Was Jesse Epstein a member of the Communist Party at the time you were?

"DR. WINTHER: Yes, he was.

"MR. HOUSTON: And he attended these Communist --

"DR. WINTHER: Yes.

"MR. HOUSTON: -- Party meetings with you?

"DR. WINTHER: Yes, sir.

. . .

"CHAIRMAN CANWELL: Is that the Jesse Epstein that was associated with the Federal Housing here in Seattle for a number of years?

"THE WITNESS: Yes" (Report of Joint Fact Finding ...).

Epstein was in California in 1948, could not be subpoenaed, and did not volunteer to testify in hearings that in later years would become widely regarded as unfair sideshows and exercises in political posturing. But Winther was the third person to accuse him, and in response to the first, seven months earlier, Epstein had issued a strong public denial. In fact, even before Winther's testimony, Epstein had been cleared of any Communist taint by the federal government's Orwellian-named "Loyalty Review Board" ("Epstein Cleared ...").

Was Jesse Epstein ever a member of the Communist Party? Did he attend party meetings in the 1930s? Given his contributions to his city, state, and nation and the perspective of time, it really doesn't matter. But in the late 1940s, the allegations were potentially devastating, and Epstein was but one of hundreds of Americans who had to endure similar treatment during that dark, dangerous era that saw a lethal mix of public hysteria and opportunistic politicians. Although he never directly said so, it is very likely that the experience played a major role in Epstein's withdrawal from public service.

Harvard, Then Home

On September 3, 1948, Jesse Epstein resigned from the Federal Housing Authority, and he would never return to government employment. He accepted a Littauer Fellowship at Harvard University, where he earned a master's degree in public administration in 1949, then returned to Seattle to practice law.

Although he was never again on the public payroll, Epstein remained very active in civic affairs. While serving as president of the Mountaineers Club in 1968, the Internal Revenue Service revoked the organization's tax-exempt status. In response, Epstein led an effort to establish the Mountaineers Foundation, a nonprofit that continues today (2014) to raise funds and make grants to environmental organizations in the Pacific Northwest, and he served as the foundation's first president. He was also active on the boards of Seattle Indian Center, Neighborhood House, Keep Washington Green, Washington Wilderness Association, and REI. Epstein retired from the practice of law in Seattle in 1985 and died four years later, on June 18, 1989, survived by his wife, Sylvia, and his two younger sisters. The Epsteins had no children.

Jesse Epstein was always modest and matter-of-fact about his contributions to the city, and outside of the public-housing community his name is not particularly well remembered. But in 2001, a panel of 18 historians, civic leaders, and journalists empanelled by The Seattle Times named him to a list of 150 people who had shaped Seattle's then-150-year history, crediting him with "introducing racial integration to Seattle" ("Metropolist 150 ...").

Epstein would not have been too impressed. He never sought publicity unless it would advance a cause for which he was working, and he rarely appeared in the local newspapers after he left government service. In the words of historian Roger Sale, who interviewed Epstein while researching his popular city history, Seattle: Past to Present, "He was the gentlest and most modest man you could know" ("Jesse Epstein's Campaigns ... "). As relatively unrecognized as he remains, his name does live on in Yesler Terrace, where the Jesse Epstein Building at 905 Spruce Street, originally constructed in 1909 as the Kenyon Apartments, has since 1979 provided office and administrative spaces to health and social-service agencies.