Coast Salish communities on Puget Sound located villages in places that offered access to resources they could use or trade. On the Elliott Bay waterfront at what is now the foot of Seattle's Yesler Way, the ancestors of today's Duwamish, Suquamish, and Muckleshoot tribal members chose a space they called Dzidzilalich, which can be translated as Little Crossing-Over Place. It was adjacent to a flounder fishery, shellfish beds, salmon fishing grounds, places to gather plant resources, and a source of freshwater. It was also a centrally located place where people could gather to socialize, make alliances, trade, and share traditional knowledge. Though the longhouses had been abandoned by 1852, when the Denny Party, Seattle's founding settlers, claimed the land, Native people continued to gather in the area and it remains important to the tribes today.

Disappearing Landscape

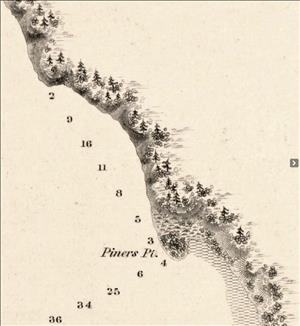

By the time anthropologists and historians began to look for traces of Dzidzilalich in the twentieth century, the longhouses at the site had long since been removed and the area had been regraded and filled to such an extent that the original landscape had disappeared. Old maps showed a point of land (named Piner's Point by early explorers), which was regularly cut off from the mainland by high tide, extending south from the area of today's First Avenue and Yesler Way. On the inland side, the maps showed a lagoon or saltwater marsh extending in to where Jackson Street is today, in the area of the train stations at 4th Avenue. The shoreline then ran south along the base of Beacon Hill and curved around to the mouth of the Duwamish River on the south side of the bay.

Just north of the island, where the land began to rise, the Duwamish built a winter village of about eight longhouses. According to historian David Buerge, the longhouses were about 60 feet by 120 feet and the village would have had a population of about 200 people. One account identifies one of the structures as a "dance house" used for ceremonial gatherings.

The People of Dzidzilalich

Dzidzilalich is primarily identified as a Duwamish village because that name has been used to identify the people living in the Seattle and Renton region. Though non-Native settlers, and particularly the territorial government, identified the Duwamish as a tribe that included people living on Lake Washington, the Cedar, Black, and Duwamish rivers, and Elliott Bay, it is more accurate to describe those Native communities as autonomous bands who shared language, customs, and social relations with other nearby bands, often living in the same watershed. The Duwamish primarily lived along the Duwamish, Black, and Cedar rivers. These rivers once formed a single drainage, but the opening of the Montlake Cut in 1916 caused the level of Lake Washington to drop about nine feet and the Black River, which formerly drained the lake, dried up, and the ship canal became the lake's outlet.

People living on the western side of Lake Washington, sometimes called the Lakes Duwamish, and those living on Elliott Bay were also included in the Duwamish tribe by early settlers and Indian agents. This grouping of autonomous bands was further formalized by the treaty process. The desire of territorial government officials to work with leaders of large groups, rather than with each band, led them to impose a different hierarchy and type of relationship, such as the concept of a chief with control over numerous bands, than what actually existed among the Duwamish or other Coast Salish people.

It is also likely that both the Suquamish from across Puget Sound and the groups from farther up the valleys of the White and Green rivers that today make up the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe also gathered at Dzidzilalich. They had close relations with the Duwamish and would have fished at locations around Elliott Bay.

A Crossing-Over Place

The area around Dzidzilalich had a number of characteristics that made it a good village site. For a people who relied on canoes to travel, the bay offered excellent conditions. The headlands on the north and southeast sides tempered the wind and waves. The beach sloped fairly quickly to open water, allowing for easy landing and launching.

The historical record also indicates that two trails led inland from Dzidzilalich (the likely source of the name "Little Crossing-Over Place"). One trail crossed over the low ground between the point and the mainland to the lagoon. The Duwamish and others fished for flounder in the lagoon. The other traversed the hills between the bay and Lake Washington, which provided a route between Elliott Bay and the Cascade foothills. Travelers paddled through the slough connecting Lake Washington with Lake Sammamish. (The slough has since straightened and is known as the Sammamish River.) From Lake Sammamish they could travel on foot up into the mountains to hunt game, gather berries, or socialize and trade with Native people from both sides of the Cascades.

On Elliott Bay, Dzidzilalich was just one of several documented places of importance to the Duwamish. To the north, there were village sites at Smith Cove, on Elliott Bay north of what became downtown Seattle, and at West Point where Discovery Park was later located. In the area of today's Belltown neighborhood, there was a camp site, a burial ground, and a trail over the shoulder of the large hill, known to non-Native settlers as Denny Hill, that has since been leveled. That trail led to the south end of Lake Union. That lake was another route to the interior, via Swatsugwithl ("Carry a Canoe"), known to the non-Native settlers as the Montlake Portage, in the area of today's Montlake Cut. There was also a place along the shore, below Belltown, known as Tuqap ("Aerial Duck Net"), where the Duwamish raised nets to catch ducks and other waterfowl as they flew between the bay and Lake Union. (It should be noted that for technical reasons, the spelling of "Dzidzilalich" and other Coast Salish names has been modified in this essay by omission of specialized characters usually used in spelling those names.)

Additional burial grounds were located where downtown Seattle is today. Each of them were covered over or dug up during the massive regrading of the hillside streets undertaken in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by the city's Engineering Department.

Rich in Resources

At Dzidzilalich and a number of other places on the hills around the bay, springs gurgled out of the ground and formed creeks. This is where we get the name for Spring Street. The springs provided drinking water; the one at Dzidzilalich supplied the first water system in Seattle, built by Henry Yesler (1810-1892) using wooden flumes.

On the south end of the bay the mouth of the Duwamish River created an enormous estuary. More than 2,000 acres of tidelands, since filled, teemed with shellfish, fish, and other marine life. Salmon-fishing stations located at Duwamish Head (the northern tip of what is now West Seattle) and in river channels that meandered across the flats took advantage of magnificent runs of salmon. A winter village called Tu'ul'altxw, or Herring's House, sat on the western bank of the river mouth. Another called Yuliqwad, or Basketry Hat, was further upstream, where Herring's House Park is today. Sites for gathering foods like horsetail, waterfowl, or smelt dotted the nearby shoreline and the riverbanks.

In addition to providing food and materials for household goods, these resources supplied a complex trade network that Coast Salish people participated in. Extending north to Alaska, south to California, and east to the Rocky Mountains, Great Plains, and Southwest, the network enriched the diet and technology of the people who lived on Elliott Bay. Oglala Lakota scholar Vine Deloria Jr. described the nature of the trade: "Because the food and other trade items were so plentiful, people had to become specialists in order to produce goods for trade. One could not simply smoke salmon because everyone did. Rather, the different villages had to develop specialty items that would be coveted by other tribes in order to participate in the trade" (Deloria, 10). The items produced by Puget Sound tribal members included dried clams; seal, whale, and dogfish oils; crabs; camas roots; berries; and salmon. When the British Hudson's Bay Company established a post at Nisqually, the Coast Salish incorporated the fur traders into their trade network, exchanging local products for manufactured goods. Likewise, when non-Native settlers came to Elliott Bay, they too became trading partners.

In addition to the resources offered by the land and sea, Dzidzilalich was a place where people came together. In the winter, an important time for ceremonial activities, people also traded, socialized, made political alliances, and shared traditional knowledge. They also competed with each other in canoe races and sla-hal, or stick game.

Change and Persistence

Not long after non-Native settlers claimed the land at the site of Dzidzilalich, in 1852, Indigenous people were no longer welcome there. In the Treaty of Point Elliott, signed at Mukilteo in 1855, the Duwamish, the Suquamish, and the tribes that would become the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe, ceded the majority of their land in exchange for payments and services. Though the tribes were expected to go to the reservation established at Port Madison on the west shore of Puget Sound, or, later, to the Muckleshoot reservation in what is now south King County, many of the Duwamish continued to live independently around the region. Some Native women married non-Native men and settled in towns.

The non-Native settlers at Seattle, who named their new town for a Duwamish and Suquamish leader (whose name has also been rendered in English as "Sealth," "Se'ahl," and "Seeathl," among other approximations) needed Native people to trade food items with them, provide transportation in their canoes, and work at Yesler's mill, the economic backbone of the settlement.

This interdependence did not translate into a desire to integrate the two cultures. The new city council officially prohibited Native residences within the city limits in an 1865 ordinance (though that law was not reinstated when Seattle incorporated a second time in 1869). As the town grew, Native people were relegated to other areas around Elliott Bay, and, as undeveloped areas along the shoreline shrank, they were tolerated on Ballast Island at the foot of Washington and Main streets, just a block or two from the site of Dzidzilalich. There are a number of accounts and photographs of Native people camped on the small bit of land, dubbed Ballast Island, created by ballast dumped from ships coming to Elliott Bay to load lumber destined for ports around the Pacific Rim.

Members of Puget Sound and visiting British Columbia tribes held gatherings with feasts and familiar activities such as canoe races and smoking salmon at Ballast Island. Local businesses welcomed their trade. With their earnings from working in sawmills and canneries, and from picking hops in the White and Green river valleys, they were early customers of banks and stores. They also traded baskets and other items for sale in stores such as the Golden Rule Bazaar. They maintained their presence on Ballast Island until the 1890s, when it was covered over by pier and trestle expansions.

Most places on Elliott Bay that were significant to the Native people who lived there would be burned or, like Dzidzilalich, covered over by regrades, buildings, railroads, and streets in the 1890s and early 1900s. Additionally, the Duwamish River was straightened and the tideflats filled in the early twentieth century. Nonetheless, these places remain important to the Duwamish, Suquamish, and Muckleshoot today, as they are to other area tribes such as the Snoqualmie and Tulalip who also have a history on the bay. Members of these tribes tell the stories related to various sites and return to many of the places regularly. The Duwamish Tribe has built a longhouse and cultural center adjacent to the former site of Yulíqwad (Basketry Hat). In 2014, tribal members continue to fish on Elliott Bay and in the Duwamish River and the tribes are actively involved in rehabilitating the environment and helping shape the future of Seattle's central waterfront, including the former location of Dzidzilalich, as it undergoes another transformation of purpose and meaning with the planned replacement of the Alaskan Way Viaduct.