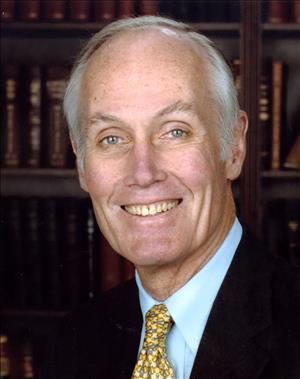

Slade Gorton, a leader in Washington's Republican Party for more than four decades, served three terms as U.S. Senator, three as state attorney general, and 10 years as a representative in the Washington State Legislature. He was born in Chicago, educated at Dartmouth College, and received his law degree from Columbia Law School. He moved to Seattle in 1953 and won his first seat in the state House in 1958. In 1967, he became the state House majority leader. He successfully ran for state attorney general in 1968 and held that post until 1980, when he defeated Warren Magnuson (1905-1989) for U.S. Senate. Gorton lost his re-election bid in 1986. However, he ran for the U.S. Senate again in 1988 and won. He was re-elected in 1994. He considered himself a "passionate moderate" for most of his career, yet made headlines for his clashes with environmentalists and Indian tribes (Hughes, 278). He was defeated in a bid for a fourth term in 2000. As a member of the federal panel charged with investigating the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Gorton was instrumental in preparing the influential 9/11 Commission Report.

Early Years in Chicago

Thomas Slade Gorton III was born in Chicago on January 8, 1928 to Thomas Slade Gorton Jr. and Ruth Israel Gorton. From the beginning he was never called Thomas or Tom, although through a long and often contentious career in politics, the boy would later acquire a variety of colorful nicknames, including Skeletor, Slade the Blade, Cyanide Slade, and Slippery Slade (Hughes, 5)

The Gorton family lineage stretched back to the early settlers in New England, who went on to found a Massachusetts cod fishing company now called Gorton's of Gloucester, famous for its fish cakes and grizzled-fisherman-at-the-helm logo. Slade Gorton was characterized throughout his political career as the epitome of, in his own words, a "Yankee Republican Protestant" (Gorton "Qualities," p. 4). Yet he was raised in Evanston, Illinois, where his father operated a Chicago seafood business, separate from Gorton's of Gloucester. The Gorton family had already sold the larger company before Slade was born.

However, his father did try to interest him in his Chicago seafood business, with hopes that young Slade would take over someday. Slade's interest faded the longer he worked in the Chicago warehouse. He said it was a "grimy, slimy, smelly place and I knew very early that I wasn't going to work 15 hours a day, six days a week at the fish business"(Hughes, 16). This was "a great disappointment to my father" (Hughes, 16).

Finding His Calling

Meanwhile, Slade had found his calling. As a high school freshman, he had attended an all-school assembly at Evanston High School, which featured a speech by Walter Judd (1898-1994), a medical missionary to China, soon to become a U.S. Representative. Judd told the students that "public service was the highest calling" and that they had "the power to make the world a better place" (Hughes, 18-19). Gorton "decided that when I grew up I wanted to be Walter Judd" (Gorton, "Qualities," p. 3-4). When he got home, he told his mother that someday he would be a U.S. senator

Both of Gorton's parents were staunch Republicans, and so was young Slade. His ensuing, often passionate, political arguments with his father weren't about Republicans vs. Democrats -- they were about progressive Republicans vs. traditional Republicans. Young Slade sided with the more progressive wing, including Arthur H. Vandenberg (1884-1951) and later, Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969).

Gorton graduated from high school in 1945 and went to Dartmouth College. Before a year was out, in April 1946, he was drafted, became a private in the U.S. Army and was sent to the Army's Weather Observer School. He served less than a year because the army, with no war to fight, discharged its new draftees early. Gorton returned to Dartmouth and excelled academically, graduating magna cum laude and acquiring a Phi Beta Kappa key and a bachelor's degree in International Relations.

Going to Law School

"I didn't have any idea what I was going to do next," said Gorton (Hughes, 21). The answer turned out to be law school. He was accepted into Yale University and offered a full-ride scholarship to Stanford. However, he turned down both of those offers and decided to live at home and attend the Northwestern University Law School.

"It was a hell of a mistake for me to go to Northwestern and live at home at the age of 22," said Gorton many years later. "I didn't get along with my parents, and I had a girlfriend at Smith College whom they detested" (Hughes, 22). He soon followed the girlfriend to New York and transferred to Columbia Law School. The girlfriend didn't last, but he persevered at the law school and graduated in 1953. He interned at a high-powered Boston firm, but Gorton realized early that he "didn't really fancy spending the rest of my life keeping my nose above water" at that kind of firm (Gorton, "Qualities," p. 4).

Choosing Seattle

He later said that he bought a one-way bus ticket to Seattle in the summer of 1953 simply because, "I got out an atlas and an almanac and it came down to Seattle"(Gorton, "Qualities," p. 4). Gorton's sights were set on politics, and he later said, "you didn't have to be very bright to know what future an impecunious Yankee Republican Protestant had in Boston" (Gorton, "Qualities, p. 4).

He had also been deeply impressed by the performance of a young Tacoma politician, Don Eastvold (1920-1999), at the Republican National Convention, and any state that could produce such charismatic young Republican leaders must be "a wonderful place" (Hughes, p. 24). He settled in to study for the Washington State Bar exam, but at the beginning of 1954, he was eligible once again for the draft, since he had served less than a year during his first stint. Instead, he entered the Air Force as staff judge advocate at Polk Air Force Base near Fort Bragg, North Carolina. He served in the Air Force for the next three years and returned to Seattle in 1956. He soon met Dan Evans (1925-2024), Jim Ellis (b. 1921) and Joel Pritchard (1925-1997), who, along with Gorton, would soon become the new faces of the Republican Party in Washington.

Entering Politics

Gorton joined the Seattle law firm of Grosscup, Ambler, Stephan & Miller and was mentored by Pendleton Miller. Gorton supplemented his income from an unlikely source -- as a winning contestant on a daytime game show titled, Tic-Tac-Dough. He went to New York in 1957 and won $3,800 by displaying what a friend jokingly called all of that "useless knowledge in your head" (Hughes, 30). In 1958, Gorton entered a different kind of contest, the kind he had been dreaming about since he was 14. He filed for an open House seat in the state's newly formed 46th District in North Seattle. His law firm did not see politics as a "fitting" arena for a lawyer, but Miller convinced the other partners to let Gorton "get it out of his system" (Hughes, 32).

With campaign advice from his friend Dan Evans, who had already won a state House seat, Gorton proceeded to, in Evans's words, work "much harder than any of his opponents" (Hughes, 33). He won the race and headed to Olympia as the session began in January 1959.

He didn't go alone. In 1957, he had met a talented young reporter for The Seattle Times, Sally Clark (1932-2013). They went to movies on Friday nights and went skiing on Sundays. She took a shine to the smart young lawyer because he "could talk about something other than cars and football" (Hughes, 33). They were married on June 28, 1958. When the session started six months later, Slade and a pregnant Sally moved into a rented Olympia home with Pritchard and Evans.

Gorton quickly established a reputation as an "ambitious smarty-pants Ivy Leaguer" -- which did not necessarily endear him to the old guard of either party (Hughes, 34). Yet he was the rare freshman representative who read every bill and parsed it carefully. The minority Republicans had little power, which meant "as a freshman Republican ... there was no way you could screw anything up," said Gorton (Gorton, "Qualities," p. 6).

He easily won re-election in 1960 and 1962. The 1963 legislative session turned out to be one of the state's most momentous sessions. Gorton, as assistant Republican floor leader, played a key role in what would become known as "The Coalition" in which six insurgent Democrats joined the Republicans to form a majority. The Republicans won committee chairmanships and had more power in the looming redistricting fights. Gorton immediately set to work on a redistricting plan, but the redistricting fight would drag on foe another two years.

The Courage of His Convictions

Meanwhile, in late 1963, Gorton was asked to do something that threatened to damage his standing with the right wing of his own party. Attorney William Dwyer (1929-2002) asked Gorton to go to the Okanogan County Courthouse to testify as a character witness for Democratic State Representative John Goldmark (1917-1979). Goldmark had been accused by political enemies of being a Communist. Goldmark was suing them for libel. Gorton knew that if he agreed to testify, "it would cost me," and if he said no, "I'd be a coward" (Hughes, p. 41). He later said this "may have been the pivotal moment in my career in politics" (Hughes, 41).

Gorton testified. He told the court that Goldmark's "reputation was excellent," and that Goldmark had never exhibited any sympathy or connection with communism ("Past Recalled"). The far-right wing of the party tried to punish Gorton by running a candidate against him in the 1964 primary, but Gorton easily beat back the challenge.

Redistricting the State

Back in the redistricting fights in Olympia, Gorton proved to be the Republicans' most potent weapon. One Republican staffer said Gorton was so smart that he could memorize all of the districts (Hughes, 57). When the 1965 legislative session began, the redistricting battle was rejoined, but this time, Gorton and the Republicans had veto power. Gorton's friend Dan Evans has been elected governor in November. Finally, in February 1965, Governor Evans signed a compromise redistricting bill into law, with Gorton standing proudly in attendance.

Thanks in no small part to redistricting, the Republicans gained a 55-44 majority in the state House in 1966, the first since 1953. Gorton easily won his fifth term, and was also elected the House majority leader. Gorton relished the role because it made him the legislative point man for Governor Evans's ambitious "Blueprint for Progress" agenda. Then, in 1967, Gorton helped push through a series of bills to prepare the way for the ambitious Forward Thrust bond issues, the brainchild of Jim Ellis. Gorton considered Forward Thrust one of his two top accomplishments, along with redistricting, during his 10-year state legislative career. He later proudly said, "I got every damn one of them passed without change" (Hughes, 77). Forward Thrust eventually resulted in the Kingdome, the Seattle Aquarium, and massive improvements to King County's highways, sewers, and recreational facilities.

Attorney General Gorton

By 1967, Gorton already had his eye on a new job: Washington's attorney general. The post combined both of his passions, law and politics. He received an enthusiastic blessing from Governor Evans, who wanted an ally in the attorney general's office. His Democratic opponent was John G. McCutcheon, a former Pierce County prosecutor and state representative. In a Republican ad campaign, Gorton was packaged with Evans and two other young Republicans as part of "The Action Team," an obvious play on The Mod Squad, a new TV series. Gorton was labeled in the ad as "The Lawyer With A Cause --Young, tough, with a mind like a steel trap and a deep concern for making Washington safe and sane" (Hughes, 89). One of Gorton's campaign brochures featured Sally and their three children, Tod, 9, Sarah, 8, and Becky, 6. On election night in November 1968, Gorton trailed McCutcheon late into the night. Yet when the absentee ballots were counted, Gorton won the post of attorney general by 5,368 votes. He would hold that job for the next 12 years.

He immediately launched into a sweeping series of consumer protection initiatives. He also went after organized gambling, because he believed gambling was "a vice" (Hughes, 89). The state's taverns and lodges were rife with card rooms, pull-tabs and punchboards -- and many churches had bingo nights. Gorton ruled that all of these games were illegal. It did not endear him to the state's many bingo-playing grannies.

"Slade Gorton is not a guy you go out and drink beer with," wrote Richard W. Larsen of The Seattle Times. "He is stern, politically tough, humorless. When I asked him why he messed up everybody's bingo, he answered with a ferocious, rapid-fire legal soliloquy"(Larsen).

Weathering a Scandal

When re-election time rolled around in 1972, Gorton had to contend with more than angry bingo players. He also had to weather a scandal in his office. While Gorton was out campaigning, his deputy, J. Keith Dysart, took it upon himself to investigate charges that Albert Rosellini (1910-2011) was connected with a Seattle organized crime family. This was politically volatile, since Rosellini, a former governor, was currently running for governor again in an attempt to unseat Dan Evans.

It created at least the appearance that the attorney general's office was engaging in dirty politics. Gorton immediately suspended Dysart and stoutly maintained that he knew nothing about Dysart's actions. Yet it gave an unsavory flavor to Gorton's 1972 campaign against Fred Dore (1925-1996). Gorton won handily on November 7, 1972, but he later called that campaign "the most unhappy period in my life" (Hughes, 96).

Covering Miles, Making Headlines

In need of something to wash the taste away, Gorton talked his family into a monumental summer adventure: riding their bicycles from Olympia to Gloucester, Massachusetts. Tod was 14, Sarah was 12 and Becky was only 11. Yet they, along with Slade, Sally and another family made the coast-to-coast trek in 45 days, spending the nights in church basements or in the homes of people they met along the way.

"That whole trip personified my dad's enthusiasm and eagerness to do everything to the fullest," Becky later said. "There's a great bit of child in him. I'm not saying 'childish'; it's his love of life. The bitter liberals have never been able to grasp that" (Hughes, 110).

When he returned to Seattle, he made headlines -- and Republican enemies -- by being the first Republican official in the state to publicly urge the Watergate-plagued President Richard M. Nixon (1913-1994) to resign. Gorton did so in a speech on March 21, 1974 -- five months before Nixon resigned.

Against Tribal Sovereignty

Meanwhile, Gorton was in the middle of a legal fight over Native American fishing rights and sovereignty. In 1974, U.S. District Court Judge George Boldt (1903-1984) ruled that Indians were entitled to up to 50 percent of the fish that passed through their usual and accustomed fishing grounds. The decision enraged sport fishermen and the state's Game Department. Gorton's office immediately filed an appeal, which, after many controversial hearings, ended up in the U.S. Supreme Court. Gorton argued the case himself -- one of 14 Supreme Court cases he would argue throughout his life -- but lost the decision, 6-3.

Through this case and several others on the subject of tribal sovereignty, Gorton gained a lifelong reputation as a staunch Indian opponent, or, as one cartoon put it, "The Last Indian Fighter" (Hughes, p. 127). The tribes regarded Gorton as the symbol of a white society that refused to live up to its promises. Gorton saw the issue as a simple case of equal justice before the law.

"I find racism appalling," he told his biographer, John C. Hughes, in 2011. "But I do have a profound difference with the tribes. I don't think they should be treated differently than anyone else. I think the same laws ought to apply to everyone" (Hughes, 128).

Last Years as Attorney General

Meanwhile Gorton had intervened in an endeavor close to his heart, baseball. After the Seattle Pilots decamped to Milwaukee in 1970, Gorton initiated a lawsuit against the American League to bring major league baseball back to Seattle. As a result, the Seattle Mariners began play in 1977. Gorton was later instrumental in keeping the Mariners in town during other crises.

In 1976, Gorton comfortably won a third term as attorney general. However, Gorton had made plenty of enemies. David Brewster of the Weekly, Seattle's increasingly influential alternative paper, noted that Gorton was increasingly unpopular and had "failed to develop a core issue or deep loyalty" (Hughes, 145). However, Brewster said a recent clumsy attack on Gorton by the Democrats had backfired and might help Gorton to "emerge at last as the state leader (and U.S. senator) he has always wanted to be" (Hughes. p. 145).

Gorton indeed craved the job of U.S. senator, yet for most of Gorton's career a pair of twin Democratic monoliths were ensconced in Washington's seats, Henry (Scoop) Jackson (1912-1983) and Magnuson. As 1980 approached, Gorton sensed that the time was finally ripe. Magnuson, at age 75, was showing his age and Gorton, at 52, was entering his prime. Advisers warned Gorton that taking on Magnuson was "like going up against Goliath without a stone in your sling," but Gorton correctly predicted that a Republican tide was flowing (Hughes, 153).

Senator Gorton

Gorton had to convince voters that new blood in the Senate was more important than seniority. He and his campaign accomplished this with a brilliant ad that asked, "Isn't it time to start rebuilding more seniority while we still have Scoop Jackson in the Senate?"(Hughes, 157). His other campaign theme showed due respect for Magnuson: "Maggie is a good man who has done good works, but it is time for him to go" (Scates, 315). Gorton began the race far behind, but 10 days before the election, polls showed him catching Magnuson and gaining every day thereafter. When the results came in on November 4, 1980, Gorton won 54 percent of the vote. He had caught the Republican wave that swept Ronald Reagan (1911-2004) into office. An overwhelmed Gorton said, "I am in awe of what we have wrought" ("Slade Gorton Retires Sen. Magnuson").

When Gorton was sworn in at beginning of 1981, he was dubbed one of "Giant Killers," who had knocked off Senate Goliaths. He proceeded to get appointments to key committees, including Commerce, Science & Transportation, Environment & Public Works, and, most crucially, Budget. On that committee Gorton would soon gain a reputation as one of the Senate's top deficit hawks.

The Boston Globe noted in 1981 that Gorton "did not wish to be identified with many of his New Right classmates" (Hughes, 178). He was "inclined to be protective of the environment, supportive of the Equal Rights Amendment, and a believer that the government should remain neutral about abortion" (Hughes, 178). His record established him as an "intellectual centrist with libertarian tendencies" (Hughes, 151).

Gorton was an early supporter of Reagan's spending cuts, but as a deficit hawk he later clashed with Reagan over the president's unwillingness to cut defense spending and deal with the need for new revenues. However, Gorton had voted with Reagan 85 percent of the time, which would end up costing him in liberal Seattle.

Gorton entered his re-election campaign in 1986 weighed down by the volatile issues of Social Security cost-of-living increases -- which he wanted to limit -- and the Hanford Nuclear Reservation. The federal government had listed Hanford as a potential nuclear waste dump site, and Gorton was portrayed as not being vigorous enough in opposing it. His opponent, Brock Adams (1927-2004), a former U.S. representative and Secretary of Transportation, hammered incessantly on the issue, saying, that the site should be named "The Slade Gorton Memorial Dump" (Hughes, 217). Gorton's increasingly desperate campaign even brought in President Reagan to stump for him, but the lame-duck president did more harm than good. On election night, Adams defeated Gorton by a narrow margin. Gorton was one of five first-term Republican senators defeated in an anti-Reagan backlash.

Slade Gorton New and Old

Gorton went back to Seattle and joined a law firm. Yet he wanted nothing more than to be back in the U.S. Senate, and his chance came much earlier than expected. Dan Evans announced that he would not run for re-election to the Senate in 1988. Gorton entered the race, and to win it he had to fashion an image as the New Slade. The New Slade promised to be a better listener, a more approachable person, and a progressive candidate with an agenda he called his "Evergreen Vision" (Hughes, 238). His opponent was former governor Mike Lowry (1939-2017). Both candidates had high polling negatives -- people either loved them or hated them. Yet Gorton's campaign succeeded in portraying Lowry as too liberal. Gorton eked out a 51 percent winning margin on election night in 1988 and he was back in the Senate after a two-year exile.

In 1989, his old friend William Dwyer, whom Gorton had backed for a federal judgeship at Gorton's considerable political cost, issued a ruling that outraged Gorton and Washington's logging industry. Dwyer blocked timber sales to protect the imperiled spotted owl, a decision that played havoc with the economies of logging towns. Gorton energetically embraced the loggers' cause, to the outrage of environmentalists. Gorton's response was, "Human beings are also imperiled" (Hughes, 259).

Despite vigorous opposition from environmentalists and the tribes, Gorton entered his 1994 re-election campaign with a solid lead over Ron Sims (b.1948), a King County council member. The Sierra Club lowered Gorton's "Environmental Batting Average" to zero, despite the fact that earlier in his career Gorton had backed a number of environmental bills (Hughes, 291). However, Gorton won the 1994 election by his widest margin ever, capturing 56 percent of the vote, helped by a massive nationwide Republican tide. He weathered a brief medical crisis -- a minor heart attack followed by an angioplasty -- but was back in the Senate by the time the 1995 session started.

Moving Rightward

Gorton had heretofore considered himself "a passionate moderate" (Hughes, p. 278). He moved rightward in his third term and quickly formed an alliance with conservative Senate majority leader Trent Lott (b. 1941), who called Gorton "one of my closest friends in the Senate -- a man I trusted implicitly" (Lott, p. 179). Gorton became a voice of bipartisan compromise during one of the Senate's biggest crises, the highly charged Bill Clinton (b. 1946) impeachment trial in 1999. Gorton joined with Democratic Senator Joe Lieberman (b. 1942) to forge a key procedural compromise to help make the trial "rapid and reasonable" (Lott, p. 181). In the end, Gorton voted not guilty on the perjury charge against Clinton and guilty on the obstruction of justice charge.

Gorton tangled repeatedly with environmentalists. In 1999, he authored a last-minute rider on an emergency appropriations bill to authorize the Crown Jewel mine, an open-pit gold mine in Okanogan County. Angry opponents dubbed him Cyanide Slade and the League of Conservation Voters named him to their Dirty Dozen. Meanwhile, his relationship with the Indian tribes couldn't have been worse. One tribal leader said he saw Gorton "as an individual that will wipe out further generations" (Hughes, 312). The tribes mounted an all-out "Dump Slade 2000" campaign blitz (Hughes, 317).

His opponent in 2000 was former U.S. Representative and tech millionaire Maria Cantwell (b. 1958), who campaigned on the themes of "new fresh leadership" and a retreat from "the politics of division" (Hughes, 331). The result was one the closest elections in the state's history -- so close that a winner was not declared until three weeks later, on December 1, 2000. After all the votes were counted and recounted, Cantwell had "retired" Slade Gorton from the U.S. Senate, just as Gorton had "retired" Magnuson.

The 9/11 Commission and Beyond

Yet Gorton was not ready to truly retire. He was appointed to several federal commissions, including perhaps the most important commission in the nation's history, the 9/11 Commission. The commission consumed almost two years of Gorton's life from 2002 to 2004 and produced the much-praised -- and bestselling -- The 9/11 Commission Report, which analyzed how the September 11, 2001, attacks had occurred and how to prevent a recurrence. Gorton emerged as one of the key members of the 10-person panel and biographer Hughes called his 9/11 work "the singular achievement of a half-century in public life" (Hughes, 7).

Well into his 80s, Gorton remained actively engaged governmental affairs. In 2010, he launched the Slade Gorton International Policy Center. In 2011, the state appointed Gorton to a panel that hearkened back to his early days as a state legislator. The panel was charged with drawing a new state-redistricting map -- a subject that perhaps no one alive knew better than Slade Gorton.

Gorton died on August 19, 2020, in Seattle. He was 92. Washington Sen. Patty Murray, a Democrat who overlapped with Gorton in the Senate, told The Associated Press upon learning of his death, "Throughout his career in both Washingtons, Slade defied convenient labels and stood on principle -- we need more leaders in our country like Slade" ("Former Senator ..."). Dan Evans called Gorton, "an intellectual giant who was always the smartest person in the room and a strategic thinker who helped define the GOP in Washington state during a time when the party could still prevail in major, state-wide contests" (Former Senator ...").