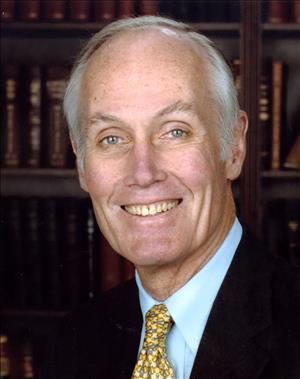

On October 31, 1986, President Ronald Reagan (1911-2004) delivers a hotly debated statement about Hanford while campaigning in Spokane for Senator Slade Gorton (b. 1928). Republican Gorton is locked in a tight re-election race against former U.S. Secretary of Transportation Brock Adams (1927-2004). Adams calls Gorton ineffectual in opposing the federal government’s proposal to make the Hanford Nuclear Reservation a nuclear-waste dump; he proposes that the site be named "The Slade Gorton Memorial Dump" (Hughes, 217). Before Reagan's speech, Gorton meets with the president in his Spokane hotel to brief him on the issue. At the Spokane Coliseum Reagan declares that the Hanford issue "will be followed to the letter" of the law (Camden and Rosenwald), and that any suggestion that his administration might intentionally "circumvent the law" is the kind of thing that "touches my temperature control" (Camden) -- an ambiguous statement, since the laws conflict. The Adams campaign seizes on this as more proof that Gorton "can’t deliver a message for the State of Washington." Gorton can only say "we have begun his [Reagan’s] education" (Camden and Rosenwald). Polls show an immediate drop in support for Gorton. Four days later he will lose the election to Adams.

President Reagan Arrives

Slade Gorton had been slipping in the polls and his advisers were split on whether a campaign visit by Reagan, whose popularity was at a low ebb, would help or hinder Gorton. They finally decided to accept a visit by Reagan, but hedged their bets by choosing to hold it in the relatively small media market of Spokane. The Adams campaign was suspicious that some kind of Halloween surprise was afoot, and suggested the president was going to drop Hanford from consideration or announce a halt to the nuclear-dump selection process. Gorton was forced to scale back expectations by saying, "There’s no way we’ll get a decision on the spot, but we’ll get his ear" (Hughes, 221).

Protesters gathered outside Reagan’s hotel room at the Sheraton-Spokane, shouting, "Prepare for the arrival of the chief Contra!" ("Reagan Arrives for Spokane Visit"). Before the speech, Gorton and his fellow U.S. Senator Dan Evans (1925-2024) met with Reagan, who gave them a copy of what he planned to say about Hanford. Gorton and Evans told Reagan it was "a noncommittal disaster" and implored him to clarify the statement (Hughes, 222). Gorton told reporters later that day that "I’m certain we got a greater and more detailed discussion of the subject than has ever been the case in the past" ("Reagan Arrives for Spokane Visit").

"We told him that we think it was wrong," said Gorton. "We hope the administration will follow the policies the Congress laid out. ... If the law is followed, as far as I'm concerned, Hanford will be dropped" ("Reagan Arrives for Spokane Visit"). Gorton implied privately that he was confident that Reagan would say something to defuse the issue (Hughes, 223).

When Reagan took the stage at the Spokane Coliseum, backed by a banner that read "Reagan-Gorton, Bringing a Bright Future to the Great Northwest," most of his speech was the same stump speech he had been giving throughout the country. Yet then he added his statement about Hanford.

Not a Winning Statement

"Slade has told me about his deep concern for the health and safety of Washingtonians, particularly as it relates to this issue," said Reagan. "On this point, Slade has gotten the ears of everyone back in the nation’s capital. Now, as you know, there were plans to begin work at Hanford this fiscal year. Well, Slade, working with Dan Evans and Mark Hatfield, persuaded the Congress to adopt a provision that stops the drilling of an exploratory shaft for 12 months. And Slade has alerted me that some people have suggested that this administration might intentionally circumvent the law. Well, that’s the kind of thing that touches my temperature control. And let me tell you I will see to it that the law on this issue is followed to the letter, and let no one tell you differently" (Hughes, 223-224).

It seemed fairly safe, but in the supercharged election atmosphere, it proved easy fodder for the Adams campaign. Democratic Governor Booth Gardner (b. 1936) charged that the Department of Energy had already violated federal law by beginning testing at Hanford. Adams called it ambiguous and "terribly disappointing" and said it was further proof that Gorton had no clout whatsoever with the White House (Hughes, 224). Gorton could only call it a first step in Reagan’s education and conceded that Reagan had offered no specific pledge about dropping Hanford from the list.

Reagan No Help

The next morning, The Spokesman-Review ran a story headlined, "Did President Reagan Address Hanford Issue or Not?," which pointed out that one federal law forbade test drilling at Hanford, while another law mandated a nuclear-waste repository in the West (Camden and Rosenwald). Which law was Reagan referring to?

Gorton would later say that the hotel meeting was the first time Reagan "had heard anything about the subject, as far as I could tell" (Hughes, 225). Ambiguous statements about Hanford were clearly not what voters were waiting to hear. Gorton’s pollsters showed that Gorton was "eight points ahead when Reagan arrived and six points behind the day after he left" (Hughes, 225).

On November 4, 1986, Brock Adams beat Gorton by a narrow margin, knocking Gorton out after one term. However, Gorton would eventually recover and win another U.S. Senate seat in 1988 and serve two more terms.

In 1987, Congress voted to drop Hanford from consideration as a nuclear-waste dump.