On January 9, 2013, Buster Simpson (b. 1942) is named as the first of five artists commissioned to create permanent public artworks on Seattle's central waterfront, which is undergoing a major years-long redevelopment. An internationally known public artist who has been documenting environmental and economic change in Seattle for four decades, Simpson is chosen to work with the designers of a new seawall that the Seattle Department of Transportation is building to replace the aging, deteriorated wall that holds back the waters of Elliott Bay from the downtown waterfront. Following the selection he begins planning a series of works to be installed at a new beach to be constructed near Pioneer Square as part of the seawall project. The seawall commission is not Simpson's first attempt to engage with the design of Seattle's waterfront. In 1974, not long after arriving in Seattle, he suggested designing what became Myrtle Edwards Park by "re-orchestrating the rubble," largely freeway-construction debris, that then lined the shoreline, rather than covering or removing it, but his idea was not adopted.

Doomed Locations

Lewis Cole "Buster" Simpson moved to Seattle in 1973 and shortly thereafter created his first "eco-art installation" (Graves, "Buster Simpson Arrives ..."). Hired to clear out the junk that had accumulated over the years in two long-vacant floors of an old warehouse above a Pioneer Square gallery, he and fellow artist Chris Jonic (b. 1950) made the project into an art exhibition titled Selective Disposal Project, selecting, adapting, and rearranging objects in the rooms, documenting everything in photos and film, and finally giving away all the usable materials they had found.

In Belltown, "where he was based from 1974 to 1987, moving from doomed location to doomed location and using the conditions of real estate as the basis for his work" (Graves, "The Outside Artist"), Simpson continued documenting and making art out of what was left behind in a rapidly changing city. He photographed and filmed historic old buildings slated to be replaced by new construction and collected discarded lumber and other materials from the doomed buildings, using the recovered objects to create works displayed in the buildings, on the streets, and in gallery shows.

Learning Lessons

In 1974, Simpson set his sights on a far larger pile of discarded rubble than any single building could provide. At the time the city was planning to create a park -- then known as Elliott Bay Park, but later named Myrtle Edwards Park -- extending north from Pier 70, the northernmost of the downtown piers, to the Pier 86 Grain Terminal. Most of that stretch of shoreline then consisted of piles of debris from demolished buildings and existing streets dumped there two decades earlier during construction of Interstate 5. As Seattle Times columnist Alf Collins described it following a 1975 visit to the area with Simpson:

"The banks and coves are covered with an avalanche of chunks of concrete. The top of the bank is mounded with other construction debris covered with natural growth.

...

"There is a wondrous assortment of building fragments in the short stretch of land including huge chunks of granite and sandstone, conglomerations of bricks, scraps of ornate tile work and whole flights of stairs" ("Elliott Bay Park ...").

Not surprisingly, the city parks department planned to remove or cover up the debris, hauling it to the shoreline to control erosion or covering it with grass, trees, and plantings to create a typical park green space. Simpson saw that as a wasted opportunity to learn from and about the city's past. Rather than paying to hide or get rid of the rubble, Simpson proposed using the money "to hire artists to rearrange the sculptural elements and the heavy equipment to move it around" ("Elliott Bay Park ..."). He called this "Creative use of Seattle's architectural rubble: As much of Seattle's history is torn down, its material, instead of rubble, could become a resource for the park" (Simpson to Chapman).

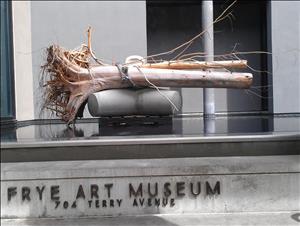

As described four decades later (in a major exhibition of Simpson's work at Seattle's Frye Art Museum), with his 1974 proposal for "re-orchestrating the rubble," called Learning Lessons, Simpson "wanted the park design to be 'honest' about its source material and for the site to reflect and document the city's own history of progress and renewal" ("Myrtle Edwards Park Proposal"). Simpson also advocated "Park development as a learning experience" -- having much of the work done by the Neighborhood Youth Corp guided by "skilled craftsmen, engineers, architects, and artists all working together" (Simpson to Chapman).

In July 1974 Simpson presented his ideas for learning lessons in the design and construction of the park at a meeting of the parks department. That September he wrote to Seattle City Council member Bruce Chapman:

"Though the presentation was received well, I felt that the Parks Department was apprehensive about the feasibility of my ideas. I believe that my ideas are feasible and could be implemented at a savings to the taxpayer and as a social service to the community" (Simpson to Chapman).

Simpson was still promoting his ideas when he toured the future park area with Alf Collins in the summer of 1975, but he did not convince the parks department or the city council. The rubble in which Simpson saw beauty and potential was removed or covered, and Myrtle Edwards Park developed like most parks with grass, trees, and landscaping.

Although Simpson's ideas for Myrtle Edwards Park were not adopted, he went on to work frequently on public-art projects with various City of Seattle departments and agencies as he built an international reputation for his public art over the next 40 years, with permanent work on display not just in Seattle but across the United States and Canada. In 2013, the same year that the Frye Art Museum mounted the first full retrospective of his career, Simpson got another chance to play a role in designing Seattle's waterfront, for which city officials and planners were envisioning a total makeover.

A New Waterfront

Myrtle Edwards Park was by no means the only part of Seattle's waterfront built over buried fill and rubble. In fact, the entire central waterfront extending south from the park all the way to Washington Street below Pioneer Square was built on fill dumped into the tidelands over the years. That central-waterfront fill was protected from the waters of Elliott Bay by a seawall built early in the twentieth century, and traversed by an elevated roadway, the Alaskan Way Viaduct, built in the middle of that century. Both aging structures were deteriorating, and after years of study, debate, discussion, and controversy following the 2001 Nisqually earthquake, city and state officials decided to build a new seawall and to replace the viaduct with a bored tunnel.

Even before work got underway (seawall construction and tunneling both began in 2013, although the tunnel-boring machine ground to an unplanned stop later that year, with timing of a re-start uncertain as of late 2014), officials began planning for the new central waterfront that would result from the two massive projects. The city hired James Corner Field Operations, a New York City firm known for its work on that city's High Line, a former elevated railroad converted into a hugely popular park, to come up with an overall design plan for a new viaduct-free waterfront.

In addition, the Seattle Office of Arts & Culture set out to commission artists to create permanent public artworks on that newly designed waterfront. Five were selected, with the last and largest commission going to Ann Hamilton (b. 1956). Multidisciplinary visual artist Norie Sato (b. 1949), sound artist Stephen Vitiello (b. 1964), and sculptor Oscar Tuazon (b. 1975) also received commissions.

The first waterfront-art commission, announced in a January 9, 2013, post on the Office of Arts & Culture's Art Beat blog, went to Buster Simpson. He was chosen to work with designers of the reconstructed Elliott Bay Seawall being built by the Seattle Department of Transportation "to develop ... artwork that will that contribute to the overall project goals of both habitat restoration and the development of public open space along the seawall" ("Buster Simpson to Create ..."). Funding for the commission came from the city's 1 Percent for Arts program, in which a small portion of construction-project costs is reserved for public art.

Anthropocene Beach

By January 2014, Simpson was designing a series of artworks to be installed at a new beach that seawall designers planned to construct on the waterfront near Pioneer Square, between Yesler Way and Washington Street. He called the piece Anthropocene Beach, a reference to the "Anthropocene Epoch," a name some scientists had recently proposed using to identify the current geological epoch as one influenced by human activity.

The name, and the materials Simpson hoped to use, reflected the same commitment to honesty about the landscape's human origins that his Elliott Bay Park proposal had years earlier. He proposed using "Anthropomorphic Pods ... as both a metaphor of human intervention and, as intended, an engineered solution to shoreline armor and anchor" ("Anthropocene Beach"). The pods would consist of "reinforced-concrete tetrapods that embrace bunches of reclaimed tree root wads and driftwood" (Graves, "The First Artists ..."). Root-wads held in place by hidden concrete tetrapods had become a common feature in habitat-restoration projects, but Simpson saw hiding the concrete as "not honest about the fact that this is a man-made intervention to correct earlier man-made environmental damage" (Graves, "Simpson, Buster"). When he exhibited a root-wad-and-tetrapod sculpture called Secured Embrace at the Frye exhibition the concrete was in plain sight, and he hoped to leave his concrete pods visible on the seawall beach -- if federal requirements to use "natural" materials in beach-habitat restoration allowed. If not, he said, "I'm hoping they will let us use sculptural stone anchors" (Graves, "The First Artists ...").

Simpson's proposals also reflected his career-long commitment to conveying the city's environmental and human history through artwork that recycled and re-used materials others might see as rubble to clear away. Stone anchors "would ... either be carved to suggest or be actual architectural artifacts," part of a "promenade where city meets beach ... would consist of inert architectural and cultural rubble reconstituted in blocks to be sliced ... into paver threshold units," and a "sitting sea wall" would be built of blocks of Wilkeson sandstone (a stone mined in Pierce County and used in the Washington State Capitol and many other historic buildings) shaped to resemble sandbags or products unloaded from ships by stevedores ("Anthropocene Beach").

Simpson even called for preserving portions of the elevated roadway whose removal from the waterfront was a primary goal of city planners. One proposed element of his beach artwork was "Alaskan Way Viaduct Totems," created by "saving ... two and possibly four or more columns as artifact relics of the Alaskan Way Viaduct," and he went beyond the confines of his own project to argue "that the vestige of a combination of footprints and columns [of the viaduct] along the entire waterfront (where possible) would provide an additional layer of meaning and complexity [in] the streetscape design and create another unifying vector" ("Anthropocene Beach").