On Tuesday morning, January 7, 1913, the oil tanker SS

Rosecrans,

from Monterey, California, bound to Portland, Oregon, with 19,000 barrels of fuel oil on board, runs aground on Peacock Spit at Cape Disappointment during a whole gale (a gale with 55-63 m.p.h winds). The wireless operator manages to send an SOS signal that the ship is stranded somewhere near the entrance to the Columbia River and is breaking up. In the thick weather, rescuers are unable to locate the

Rosecrans,

and she founders. The vessel and cargo, valued at $225,000, are totally destroyed and before assistance arrives, 33 of the 36 members of her crew perish. Only six bodies will be recovered from the mass of oil that fouls the shorelines of Washington and Oregon for many months. In terms of lives lost, the wreck of the SS

Rosecrans

is the second greatest maritime disaster recorded on the Columbia River Bar in the twentieth century.

Biography of a Vessel

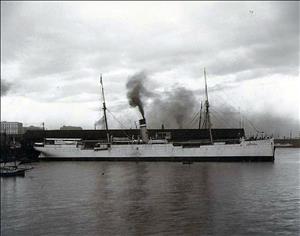

The steamship S.S. Rosecrans was built in 1883 at Glasgow, Scotland, as the passenger ship Methven Castle. The 2,979-gross-ton vessel was 326 feet in length, had a 38-foot beam and a 21-foot draft. In 1898, she was renamed Rosecrans while in service with the U.S. Army during the Spanish-American War (1898) as a troop transport. In 1903, the vessel was purchased by the Matson Navigation Company for $50,000 and put into service on a route servicing Alaska and Hawaii.

Her owner, Captain William Matson (1849-1917), had the Rosecrans converted into an oil tanker, an oddity at the time. In 1906, the ship was purchased by the Associated Oil Company to move petroleum products from its California refineries to ports on the Pacific Coast as well as Alaska and Hawaii. During this time, the Rosecrans was involved in at least two incidents that would have destroyed lesser ships. But she was always repaired, and put back into service. As a result, sailors dubbed the Rosecrans a "hoodoo" or bad-luck ship.

The Fateful Day

On Saturday afternoon, January 4, 1913, the tanker SS Rosecrans, commanded by Captain Lucian Field Johnson (1884-1913), departed the Associated Oil Company pier at Monterey, California, laden with 19,000 barrels of fuel oil for delivery to Portland, Oregon. The voyage up the Pacific Coast was uneventful until early Tuesday morning, January 7, 1913, as the vessel approached the entrance to the Columbia River. At about 3:00 a.m., the Rosecrans passed Tillamook Rock Lighthouse, 25 miles south of the mouth of the Columbia River. The weather was thick and rainy with a whole gale (55-63 m.p.h winds) gusting from the south. The radio operator at Astoria’s commercial wireless station received a message from the Rosecrans that the ship intended to cross the bar at daybreak, weather permitting, when tidal conditions would be most favorable.

At 5:15 a.m., the radio operator at Astoria received an SOS signal from the Rosecrans that the vessel had stranded on the Columbia River Bar and was breaking up, but was unable to give her position. The operator immediately transmitted a general distress call but got no response from any other vessels in the area. He then called the Puget Sound Tugboat Company at Astoria and asked the agent to notify the lifesaving stations at Point Adams in Oregon and at Cape Disappointment in Washington about the ship in distress. He then signaled the North Head Light Station to watch for any sign of the tanker. The storm had downed telephone lines from Astoria to Cape Disappointment, but the Puget Sound Tugboat agent succeeded in getting word to Point Adams.

After grounding, Captain Johnson ordered that oil be pumped overboard to reduce the ship’s draft and signaled the engine room to "full astern." Fearful that sparks might ignite the fuel vapors, Captain Johnson told the wireless operator to shut off the transmitter. As the Rosecrans started backing off the shoal, waves crashed over her, sweeping away the hatch covers and lifeboats. Seawater poured through the companionways and open hatches, flooding the lower decks and dousing the fires in the boiler room. The electrical generator short-circuited and the lights went off and leaving the tanker blacked out. The crew took shelter in the pilothouse to await rescue, which they hoped the distress call would bring. However, no one on shore had any information as to the position of the Rosecrans and the ship hadn’t signaled her distress with whistles, rockets, or flares.

The Rosecrans had grounded on the outer reaches of Peacock Spit, approximately two-and-a-half miles west of Cape Disappointment. Just before daybreak, waves carried away her funnel and foremast and the tanker broke in two. The Rosecrans settled onto the shoal with only her pilothouse and mizzenmast visible above the surf. The crew remained protected inside the tanker until about 9:00 a.m. when pilothouse started to give way, forcing all hands to make for the mizzenmast and climb into the rigging.

At 8:40 a.m., a lookout on the McKenzie Head watchtower at Cape Disappointment spotted the Rosecrans wallowing in the sea on the west side of Peacock Spit. He contacted the Cape Disappointment Lifesaving Station and informed Captain Alfred Rimer of his discovery. Captain Rimer went to the tower to estimate the Rosecrans’ position and then telephoned the lifesaving station, instructing the crew to make ready the self-righting and self-bailing, 36-foot motor surfboat Tenacious for the rescue mission. The Tenacious made three attempts to cross the bar, but found it impossible to make headway through the gale and heavy breakers. After battling the elements for three hours, Tenacious reluctantly returned to station to wait for a break in the weather and tide.

Captain Oscar S. Wicklund, keeper of the Point Adams Lifesaving Station, had been occupied all morning trying to locate the Rosecrans, thought to be foundering somewhere on Clatsop Spit. He dispatched men to reconnoiter the south jetty and Clatsop Beach for any sign of the tanker, but they found nothing. He then ordered his crew to make ready the 36-foot motor surfboat Dreadnought for sea. As the Dreadnought approached the mouth of the Columbia River, she was overtaken by the powerful 128-foot Puget Sound Tug Boat Company towboat Tatoosh, outbound on the same rescue mission. While the surfboat sheltered lee of the south jetty, the Tatoosh made a sweep of Clatsop Spit but saw no trace of the Rosecrans. Captain Wicklund returned the Dreadnought to Point Adams to await further developments.

Meanwhile, the Port of Portland 103-foot tugboat Oneonta, commanded by Captain Charles E. Anderson, and the Puget Sound Tug Boat Company 80-foot tugboat Fearless, commanded by Captain Edward D. Parsons, crossed the bar to search for the foundering tanker.

As telephone lines were down between Oregon and Washington, Captain Wicklund decided to take the Dreadnought across the river to Cape Disappointment to see if Captain Rimer had any information about the ship in distress. As he was preparing to depart, he received a message from Fort Stevens that the Rosecrans was aground on Peacock Spit and sailors could be seen in the rigging. Knowing that two surfboats would be required for the rescue mission, Captain Wicklund immediately got under way for the Cape Disappointment Lifesaving Station. Upon his arrival there, he found the crew of the Tenacious was out patrolling the ocean beach looking for survivors. Rather than wait, Captain Wicklund immediately headed his surfboat toward Peacock Spit. The Dreadnought made two attempts to cross the bar but was thwarted by high wind and waves, and so returned to Cape Disappointment.

At about 12:30 p.m., the surfboats Tenacious and Dreadnought made a further attempt at crossing the bar. The tide had slackened and the wind had moderated somewhat, allowing the vessels to reach to Peacock Spit. All that could be seen of the Rosecrans was the mizzenmast with three sailors clinging to the rigging. As the Tenacious circled the wreck, looking for survivors, the Dreadnought ran in close to the port side of the Rosecrans and signaled the sailors to jump overboard, but they would not. During the fifth precarious trip around the wreck, a wave nearly capsized the Dreadnought, sweeping Captain Wicklund and five surfmen overboard.

Climbing back aboard the Dreadnought, Captain Wicklund saw that the wave had capsized the Tenacious and the crew was signaling for assistance. Her hull had been cracked, the airtight compartments compromised, the rudder and steering disabled, and the engine had stopped. The Dreadnought responded to this new emergency and towed the damaged surfboat to the tugboat Fearless that was standing by outside the line of breakers. That accomplished, the Dreadnought returned to the Rosecrans and rescued two survivors, Erick Lundmark and Johan Slinning, who had finally leaped from the rigging into the sea. The third sailor, Joseph Cagna, fell from the rigging into the water. The surfmen saved him, but he died from a severe concussion a short while later.

It was now late in the afternoon, the sea was high and the tide running out. Since the Dreadnought had no chance of safely crossing the bar, Captain Wicklund set course for the 135-foot lightship Columbia (light vessel No. 88) stationed five miles due west of the Columbia River’s mouth. In the terrible storm the voyage took three hours, and the surfmen had considerable difficulty climbing aboard the lightship. The Dreadnought, with Cagna’s body lashed to a thwart, was tethered to the Columbia with 300 feet of four-inch line.

Meanwhile, the tugboat Fearless started towing the Tenacious, with all hands still aboard, toward Astoria. Captain Parsons soon realized that the damaged and disabled surfboat would never survive the passage over the bar, and brought the surfmen aboard the tug. It was a wise decision because the four-inch-thick towline parted while the Fearless was making her way through the breakers and the Tenacious was destroyed.

The intensity of the gale increased over night and by Wednesday morning, January 8, 1913, the ocean waves were mountainous. The crew made three attempts to haul the Dreadnought alongside the lightship Columbia but the storm made the task impossible. At 9:00 p.m., the watch found that the line had parted and the surfboat, with Cagna’s body aboard, had gone adrift. It wasn’t until the following day, January 9, that the weather moderated sufficiently to allow the tug Oneonta to pick up the survivors and surfmen from the Columbia. After putting the Dreadnought’s crew ashore at the Point Adams pier, the tugboat took survivors Slinning and Lundmark to Astoria where they were cared for by Associated Oil Company representatives. The Dreadnought was never seen again.

The third and last survivor was Quartermaster Fred W. Peters. On Tuesday morning, when breakers forced the crew to abandon the pilothouse, he was swept overboard. Fortunately, he was wearing a tule life-vest and managed to grab hold of a plank floating in the water. The wind and current took Peters north along the Long Beach Peninsula and, after five hours adrift, he washed ashore at Tioga, approximately seven miles from scene of the wreck. A beachcomber found Peters lying helpless on the sand and helped him to a nearby house where he was given first aid for a head wound, bruised knee, and sprained shoulder. The Klipsan Beach Lifesaving Station took charge of Peters and notified Astoria, via the meteorology station at North Head, of his remarkable survival.

During the storm, scores of volunteers from communities on the Long Beach Peninsula patrolled the 28-mile shoreline from McKenzie Head to Leadbetter Point, at the entrance to Willapa Bay, looking for sailors from the Rosecrans. The bodies of six crew members washed up near Long Beach, including that of Captain Johnson. They were taken to Astoria for identification and disposition. Captain Johnson’s remains were sent to San Francisco aboard the steamship S.S. Roanoak for burial at the San Francisco National Cemetery with full military honors. A U.S. Navy veteran, Captain Johnson had served aboard the heavy cruiser U.S.S. Olympia, Admiral George Dewey’s flagship at the Battle of Manila Bay, as an enlisted man during the Spanish-American War (1898).

The Investigation

On Tuesday, January 14, 1913, Inspector Johnstone Hamilton Quinan (1861-1940), U.S. Lifesaving Service, arrived in Portland from San Francisco to investigate the foundering of the Rosecrans and the efforts of the lifesaving crews during the rescue that had resulted in the loss of two motor surfboats. A parallel inquest was held by Captains George F. Fuller and Edward S. Edwards, U.S. Steamboat Inspection Service, to determine liability for the disaster.

After five days of investigation, the inspectors concluded the disaster resulted from poor judgment and carelessness by the watch on the bridge, responsible for the navigation and safety of the vessel. The southerly gale and strong northerly current caused the Rosecrans to overrun her course and misidentification of the navigation lights at the entrance to the Columbia River resulted in the tanker running aground on Peacock Spit. Why the ship had failed to sound her whistle or set off distress rockets and flares to make her position known was undetermined. In the dark and extreme weather, it was impossible for rescuers to locate the foundering tanker in time to save her crew.

On April 14, 1913, the Treasury Department awarded the Point Adams and Cape Disappointment surfmen gold lifesaving medals for their heroic efforts in attempting to rescue the crew of the wrecked Rosecrans. Captains Parsons and Anderson, masters of the tugboats Fearless and Oneonta, received personal letters from Treasury Secretary William G. McAdoo (1863-1941) commending them for exceptional service on behalf of the U.S. Lifesaving Service and the American people.

The Associated Oil Company had the Rosecrans insured with the San Francisco Board of Marine Underwriters for $50,000 and Lloyds of London for $175,000. Captain Albert Crowe, surveyor for the Marine Underwriters, and Edward M. Cherry, agent for Lloyds, personally surveyed the wreck to determine whether salvage was possible. Unsurprisingly, they concluded the tanker and her cargo were a total loss.

In terms of fatalities, the foundering of the SS Rosecrans was the second greatest maritime disaster recorded on the Columbia River Bar in the twentieth century. The greatest was the wreck of the SS Iowa on Peacock Spit with a loss of 34 lives on January 12, 1936.

Survivors

Erick Lundmark, carpenter

Fred W. Peters, quartermaster

Johan Slinning, quartermaster

Bodies Recovered

John L. Adams, second assistant engineer

Charles Cross, chief cook

Lucian Field Johnson, captain

Angus McDonald, messman

Hans Tonder, second mate

James Yeates, second cook

Lost at Sea:

Charles Alt, fireman

Armstrong, quartermaster

Bryant, messman

Joseph Cagna, fireman

Milton Elletson, electrician

Norman Fife, third assistant engineer

Severin Gjosen, seaman

Richard Grundell, chief engineer

Richard Hannan, fireman

William Harden, fireman

Pete Hareide, fireman

Henry Hendrickson, quartermaster

Knut Larsen, seaman

John McGlinchy, fireman

John A. McPherson, first assistant engineer

Mihan, seaman

Thomas Mullins, first mate

Christopher Murphy, fireman

Stephen O'Hare, fireman

John Olsen, fireman

C. R. Palmer, third mate

Lawrence A. Prudhont, wireless operator

Hjalamar Reistad, seaman

Charles Smith, fireman

Thomas Stensvig

Peter Uren, boatswain

Fred Wilson, chief steward