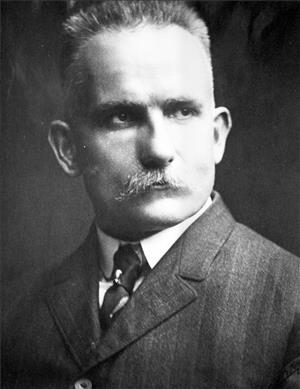

Robert Moran arrived in Seattle in 1875 at age 18, alone, with just pennies in his pocket. By 1900, he was one of the city's wealthiest and most-respected businessmen, head of a major shipbuilding company, twice elected mayor, credited with helping Seattle rebuild and modernize after a devastating fire in 1889. The apex of his career came in 1904 when his shipyard launched the battleship Nebraska. At that point he was also a self-described "nervous wreck," exhausted by overwork and "ticketed for Lake View Cemetery" ("Robt. Moran ..."). He sold the company and retired to Orcas Island, where he bought more than 5,000 acres and began developing an elaborate estate he named Rosario. The centerpiece was a 54-room mansion that he designed himself. He later donated most of his land to the state for what became Moran State Park. In 1938, widowed, with his children grown, he sold the rest of his property and moved into a small house elsewhere on Orcas. "I sleep probably better than I did at Rosario," he said, adding "it would be no burden for me" to live as he had when he first came to Seattle, hungry, broke, and looking for opportunity (Moran, 25).

Ten Cents in His Pocket

Robert Edward Moran was born in New York City on January 26, 1857. He was the third of ten children born to Edward Moran (1828-1903), an iron worker and machinist whose parents had emigrated from Ireland, and Jean Boyack Moran (1828-1879), a native of Scotland. By 1860, the family was living in Bloomfield, New Jersey. Edward Moran served as an engineer on a Northern warship during the Civil War and earned a reputation for heroism. However, he returned from the war "an embittered man, very hard to get along with" (Peacock, 11). He moved the family to nearby Montclair, New Jersey, where he made parts for Singer sewing machines and put his oldest sons to work helping him. Most of the boys, including Robert, ended up rebelling and running away.

Moran once said his mother was "the grandest mother of ten that ever lived" (Moran, 5). He made no public comments about his father. His feelings might be implied, however, by this remark, made in 1939, after he had outlived both his parents and all of his siblings: "The Creator seems to have reserved myself who proved to be the real father of the children" (Moran, 25).

He left home and apprenticed himself to a machinist in New York City at age 14. Three years later, inspired by the popular adage "Go West, Young Man," he went to Cincinnati. He spent a summer there working as a millwright's helper in a scrap-iron rolling mill on the Ohio River. He then returned to New York, with savings of $150, and bought a steerage ticket to San Francisco via Panama. He arrived in San Francisco in October 1875 but couldn't find a job. He spent his last $15 for a ticket on a steamship to Seattle, a then-remote sawmill town of about 1,500.

The story of Moran's arrival in Seattle would be told and retold, by himself and others, over the years. By his account, he landed at Yesler's Wharf at 6 a.m. on November 17, 1875, with no more than a dime to his name. "I was dumped out without breakfast," he recalled. "As my capital account was then reduced to ten cents, I was in a very embarrassing social and economic condition" (Moran, 6). He walked up the wharf to a restaurant owned by William Grose (1835-1989), an African American pioneer known for his size (six feet two inches, about 430 pounds) and generosity. "Big Bill" agreed to feed him on credit until he could find work. Moran never forgot that first breakfast: sausages, pancakes, and coffee.

Young Engineer

Grose helped Moran get his first job in Seattle, as a cook in a logging camp on the Squak Slough, near Lake Sammamish. "Whether my board bill credit was in Bill's judgment amounting to a dangerous financial point I do not know," Moran joked later (Moran, 8). It didn't go well. Moran had no experience as a cook. He lasted only three days before the camp boss gave him his wages (a total of $3) and told him his services were no longer needed. A company boat dropped him off on the north end of Lake Washington. It took him all day to walk back to town, through heavy timber and rough terrain, and when he got there his shoes were ruined. The cost of a new pair? Exactly $3.

Moran established his foothold in the Northwest by working on Puget Sound steamships. He started out as a deckhand on the steamer Zephyr. At one point he met George W. Bulline, a federal boiler inspector. Bulline began tutoring the young man in mathematics, mechanical engineering, and drafting. Moran spent virtually all of his spare time on his studies, meanwhile advancing steadily, from deckhand (at $25 a month) to fireman (at $40 a month), finally earning a license as a chief engineer.

He worked hard and lived frugally and, by 1877, had saved more than $500. He used most of the money to bring his mother and four of his younger brothers and sisters to Seattle -- something "I had first planned when I arrived in Seattle in 1875" (Moran, 10). He encouraged his other siblings to join him. The 1880 federal census showed him living in a house on Sixth Avenue between University and Seneca Streets with his brothers Peter, then 25; William, 21; Paul, 16; Sherman, 14, and Malcolm, 13; along with sisters Annie, 17, and Nora, 12. Their mother had died and was buried in Lake View Cemetery the previous year. An eighth sibling, Frank, moved to Seattle in 1889. Their father was living alone in New Jersey when he died in 1903.

In 1879, Moran shipped out as chief engineer on the steamboat Cassiar, bound for the Stikine (then commonly spelled "Stikeen") River in Alaska. At one point that summer, John Muir (1838-1914), the celebrated naturalist, and a group of Presbyterian missionaries chartered the Cassiar for a voyage to Tlingit outposts. Muir and the young engineer spent quite a bit of time together during that trip and again the next year, when Muir returned to Alaska on the Gertrude, with Moran as its engineer. Moran said later that his friendship with Muir influenced his decision to donate land for a state park on Orcas Island.

Establishing a Business

In late November 1881, Moran married a young Canadian named Euphemia Melissa Paul. Born in London, Ontario, on January 22, 1857 (four days before Moran), Melissa or Millie -- as she preferred to be known -- emigrated to Seattle in 1879. She met Moran while she was working as a domestic in the home of one of his friends. The newlyweds lived in the house on Sixth Avenue with Moran's siblings before establishing a household of their own nearby. By 1890, they had moved into a house at 216 Lenora Street that was large enough to accommodate their growing family: sons John Malcolm (born March 21, 1884) and Frank Goding (September 28, 1885) and daughter Nellie Melissa (November 24, 1890). A fourth child, Malcolm Edward, would be born September 29, 1894. The couple would later adopt a young niece, Mary Roberta (born August 19, 1894). Three other children died in infancy.

Moran quit steamboat engineering in 1882 and, with his brothers Peter and William and $1,600 in capital, opened a marine-repair and machine shop on Yesler's Wharf. The original shop was only about 300 square feet, but the brothers soon moved into larger quarters on Western Avenue. Moran traveled to San Francisco to buy equipment. "It was typical of him," a friend wrote, that he spent every dollar he had on one machine, a lathe, but it was "the best that money could buy" (Conover, 26).

Moran made a number of important contacts during his early years in Seattle, among them Bailey Gatzert (1829-1893), a prominent businessman and former mayor. In 1887, he and Gatzert organized the Seattle Dry Dock and Shipbuilding Company -- an enterprise that was backed by $75,000 in initial capital. Gatzert served as the company's president and Moran as vice president and manager. Moran's brothers Peter, William, Paul, and Sherman were elected to the board of trustees later.

The company built a sectional floating dock at the foot of Charles Street on the tideflats south of Pioneer Square in January 1888. Moran acquired title to a large tract of adjacent property and began planning to relocate and expand the machine shop he was operating with his brothers. Meanwhile, he won a seat on the City Council (then called the Common Council) -- a reflection of his increasing stature in the community.

Mayor Moran

Moran had become involved in local politics in the wake of anti-Chinese riots that roiled Seattle in February 1886. Mobs had swept through the city's Chinatown, rounding up terrified occupants and forcing hundreds onto ships bound for San Francisco. The unrest gave rise to two new political groups: the People's Party, which supported the expulsion of all people of Chinese ancestry from Seattle; and the Loyal League, organized by business and civic leaders who sought a restoration of "law and order."

The People's Party prevailed in the first election to be held after the riots (at that time, municipal elections were held on the second Monday in July; mayors and councilmen were elected for one-year terms). On July 12, 1886, William H. Shoudy (1830-1901) defeated the Loyal League's candidate for mayor, Arthur A. Denny (1822-1899), one of the founders of Seattle. The next year, the Loyal League put together a slate of candidates for a "Citizens' ticket," including Thomas T. Minor (1844-1889) for mayor and Moran for the council. Both won handily.

Moran, nominally a Republican, ran for mayor on the Citizens' ticket in 1888. He was backed not only by the Loyal League but by the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, then the city's leading newspaper. "Robert Moran is the only candidate for mayor who is in any sense representative of the workingmen of Seattle," the paper editorialized, describing him as "a young businessman against whose character or reputation not one word can be truthfully said" ("The People's Party"). The P-I reported the election results on July 10 with the following headline: "A Big Victory: Entire Citizen's Ticket Elected."

Moran took office on July 30, 1888, at age 31. One of his first acts as mayor was to send a letter to the council calling for the creation of a publicly owned water system. Seattle's water at the time was distributed by private companies that obtained it from springs or pumped it from lakes Washington and Union. The springs could not supply enough water for the rapidly growing city; the lakes were increasingly polluted and the cost of pumping water from them was so expensive the city had to skimp on fire hydrants. Moran proposed that the city build a publicly owned system that would draw water from the pristine Cedar River, deep in the Cascade foothills, and use gravity rather than pumps to deliver it. He supported a public rather than a private system even though his friend and business associate Bailey Gatzert was one of the owners of the Spring Hill Water Company, the largest of the private companies serving Seattle.

The council endorsed the basic tenets of Moran's plan and called a special election to seek voter approval of $1 million in revenue bonds to finance the project. However, a week before the election, Moran discovered a procedural error in the way it had been scheduled. The vote had to be postponed for eight months, until the next general election, to be held July 8, 1889.

The Great Fire

The inadequacies of the existing water system were dramatically demonstrated on June 6, 1889 -- one month before the election -- when most of the downtown area burned to the ground. What became known as the Great Seattle Fire broke out in a cabinet shop at Front (later renamed 1st Avenue) and Madison streets. Within 20 minutes, it had spread throughout the entire block. One of the city's two fire engines tried to pump saltwater onto the burning buildings, but the tide was out and the hoses couldn't reach the water. The second engine hooked up to the Spring Hill company's water main, but the pressure was so low that only weak streams came through the hoses.

Moran took control of the volunteer fire department and ordered the block-long Colman Building to be blown up, hoping to create a gap that would contain the fire, but the flames jumped over the wreckage and spread to the harbor. By the time it was over, 29 blocks, covering more than 60 acres, lay in ruins, along with most of the city's wharves and its railroad terminals.

On election day, voters approved the bonds for construction of a public "water works" by the lopsided margin of 1,875 to 51. They also rewarded Moran's prescience in advocating for an improved water supply and his leadership in organizing relief efforts by re-electing him as mayor.

At Moran's direction, the city hired Benezette Williams (1844-1914), an eminent hydraulic engineer from Chicago, to design the new water system. Financial and other difficulties would delay the project for nearly a decade, but meanwhile, the city bought out the Spring Hill company and took over its operations. Of all his accomplishments as mayor, Moran was proudest of his role in that transaction. "My most notable work as Mayor was the conclusion of negotiations to close down the Spring Hill Water Co.'s contaminated Lake Washington supply," he wrote, adding that the company's "inadequate plant" and "primitive water supply" were "largely responsible" for the widespread destruction caused by the fire of 1889 (Moran, 19).

Rebuilding, Expanding

Moran's machine shop on Western was among the many casualties of the fire. He estimated the loss at $40,000. But within 10 days, he and his brothers were open for business in temporary quarters on the tidelands they had acquired at the foot of Charles Street. A reorganized Moran Brothers Company was incorporated on December 19, 1889, with $250,000 in capital (compared to the $1,600 that had launched the business just seven years earlier). Robert Moran held the titles of president, secretary, and treasurer. Peter served as vice-president, Sherman as assistant superintendent, and Frank as foundry foreman.

The Moran brothers expanded from marine repair into shipbuilding at the new location. They launched their first steamship in 1890. By 1892, their shipyard covered nearly 15 acres on the Seattle waterfront. It included a sawmill, iron and brass foundries, a large marine railway, and one of the best-equipped dry docks on the West Coast. The company boasted that it could haul any Puget Sound steamship out of the water and into dry dock for repair within 12 minutes. A self-taught engineer, Moran designed some of the equipment himself, including "hydraulic lifting docks" that he patented in 1892. He received another patent in 1903, for a refuse burner and steam generator that produced power for the shipyard and foundries by burning sawdust, shavings, and scrap lumber from the sawmill.

In 1892, Moran won a contract to design and build a pumping plant and engines for the navy yard at Bremerton. Other government contracts followed, including the navy torpedo boat Rowan, the Coast Guard cutter Golden Gate, and the transport ship Seward. This work helped the company prosper despite a four-year national recession that began in 1893.

Klondike Gold

The company prospered even more after the discovery of gold along the Klondike River in Canada's Yukon Territory. News of the strike, which reached Seattle in 1897, set off a frenzy of demand for boats that could be built or retrofitted for the Yukon trade. The Morans were swamped with business. They also faced a critical labor shortage, caused in part by the number of workers who quit their jobs and headed north. The need for labor was so acute that the company placed advertisements in Eastern papers. "Requesting ships' carpenters, plankers, caulkers and first class mechanics, wages 35 cents per hour," read one ad. "We have no time to carry on correspondence" (quoted in Peacock, 22).

The preferred route to the gold fields was by boat from Seattle to St. Michael in Alaska and from there up the Yukon River to the Klondike. The conventional wisdom was that vessels with a draft shallow enough to navigate the rivers would have to be built in Alaska, because they would not be stable enough to withstand a deep-sea voyage from Seattle, through latitudes subject to frequent storms. "Experienced nautical men said it was an impossible feat to take these light draft vessels on the long trip to the mouth of the Yukon," one of Moran's friends recalled (Conover, 27). Moran set out to prove them wrong.

Between January and May 1898, the Moran shipyard built 14 paddlewheel river steamboats for the Yukon trade. Two of the boats were disassembled and the materials shipped to Dutch Harbor, Alaska, where they were to be reconstructed under the direction of Paul Moran. The remaining 12 steamers, along with six freight barges, were launched from Seattle on the first of June. The boats went under their own steam, with a full crew on each. Moran sailed with the fleet on the flagship, christened Pilgrim. One vessel was wrecked on a reef during a severe storm, but the crew was rescued and the other boats arrived safely at St. Michael after a voyage of 61 days. From there, they took supplies to prospectors on the upper Yukon.

Moran's personal triumph was overshadowed by the death of his younger brother Paul, who died of diabetes at age 34 while supervising the assembly of the two steamboats in Dutch Harbor. Paul was the second of Moran's brothers to die, following Malcolm, the youngest, whose death, in 1890 at age 25, was also attributed to diabetes (a disease that would claim the life of yet another brother, William, in 1909). Paul and his wife, Angeline, had a young daughter, Mary Roberta, who was not quite four years old. Robert and Melissa Moran adopted her and raised her as one of their own.

Battleship Nebraska

Profits from the Klondike allowed the Moran Brothers to buy out the Seattle Dry Dock and Shipbuilding Company (for a reported $350,000), doubling the size of their shipyard. They built a new 400-foot-long dry dock with a lift capacity of 8,000 tons. Since 1890, when it opened, the Moran yard had launched more than 100 vessels. Its workforce was one of the largest and most experienced on the West Coast. For all these reasons, the Morans were in a good position in the fall of 1900 when the Navy called for bids for the construction of a 15,000-ton battleship.

The bids were opened in Washington, D.C., in late December 1900. The Morans' proposal was lower than any of their competitors but still about $300,000 more than Congress had appropriated. Robert Moran, in Washington for the bid opening, sent a telegram to the Seattle Chamber of Commerce. If the city's businessmen and citizens could raise $100,000, he wrote, the Morans would scale back their bid in order to win the contract. A small group of business leaders immediately pledged $32,900. The rest of the money was raised within a week, in a campaign orchestrated by the Chamber and supported by the city's newspapers. "All grounds for doubt that Seattle would get the battleship contract were removed yesterday," The Seattle Star reported on January 8, 1901. By the end of the month, 534 individuals and companies had contributed a total of $106,740 to the battleship fund, in amounts ranging from $10 to $5,000, all carefully recorded in a ledger kept by the Chamber.

The contract was formally awarded on March 7, 1901. Two months later, several labor unions launched a nationwide strike against shipyard owners, including the Morans. Work on the battleship was delayed until June 1902, when Moran himself helped negotiate a settlement of the strike. Employment at the Moran yard ramped up quickly after that, from about 750 to more than 2,000; about half the workers were involved in building the ship that was to be christened the USS Nebraska.

An estimated 40,000 people crowded into the shipyard and adjoining piers to celebrate the launching of the battleship on October 7, 1904, and another 15,000 watched from boats on Elliott Bay. It was one of the largest crowds assembled in Seattle up to that point. The governors of Washington and Nebraska and numerous other dignitaries were present but the man of the hour was Robert Moran. Seattle Mayor Richard A. Ballinger (1858-1922), one of many speakers at the ceremony, compared Moran's accomplishment to Napoleon's victorious march over the Alps into Italy: "Our great captain of industry, in like manner, swept all obstacles aside and with Napoleonic courage, built the ship" ("The Battleship Nebraska Takes ...").

The Nebraska was not officially turned over to the Navy until July 1, 1907. It spent more than two years in the shipyard while the superstructure was completed and engines, armaments, and other equipment installed. Change orders issued by the Navy added to the time and expense of outfitting the ship. The final cost was $6.8 million -- nearly double the amount of the original contract. The Nebraska -- the only battleship to be built in Washington -- toured the globe as the flagship of the "Great White Fleet" in 1908 and 1909 but never saw action in battle. It was used as a troop transport ship during World War I and then decommissioned. It was sold to a California scrap dealer for $37,100 in 1923.

"Worn Down Man"

Moran began experiencing health problems around the time that the Nebraska was being readied for launch. His doctors told him he had organic heart disease and, at 47, might not have more than six months to live. He traveled to Europe to consult specialists, took various "cures," bought and studied medical books, and came up with his own diagnosis. "My real trouble was a highly nervous condition brought on by a badly overworked physical and mental life," he wrote, in 1939 -- at age 82. "I was a worn down man ... who needed mental rest" (Moran, 24).

He took a pleasure cruise through the San Juan Islands (lying between mainland Washington and Vancouver Island) and noticed a lumber mill that had been established in 1887 by brothers E. P. and Andrew Newhall at Cascade Bay on the east shore of East Sound, Orcas Island's long central inlet. A few homesteaders were farming land to the east, around Cascade and Mountain Lakes, but there was little other development in the area. Moran began quietly buying up land, using various real-estate agents and recording some of the deeds in the names of family members. His first major purchase, reported in the San Juan Islander on January 25, 1905, was the mill and its valuable water rights, along with Andrew Newhall's house and a farm that had been established by pioneer Payton Reddick (1843-1919). Moran eventually bought more than 5,000 acres on Orcas -- about one-third of the eastern part of the island -- an area that included four lakes, huge tracts of unlogged forest, most of 2,409-foot Mount Constitution, and miles of waterfront.

He continued to supervise work on the Nebraska but also took steps behind the scenes to sell the shipyard and retire to Orcas. News of an impending sale was first reported by The Seattle Star on January 23, 1906, in a front-page story headlined "Shipbuilding Plant of Moran Company Goes to Eastern People." Moran staunchly denied the report, for weeks. Finally, on March 16, 1906, he confirmed that Moran Brothers had been sold to the New York firm of Berton-Griscom and Company. The sale price was a reported $3.5 million (about $90 million in 2015 dollars).

Moran said he would continue to oversee the outfitting and testing of the battleship but that he had no other plans: "I am not able to say at this time what I will do in the future. I don't even know that I will have dinner today, although I presume I will" ("Robert Moran Tells of Sale"). He told friends that he had "accumulated sufficient to live upon, educate his children and gratify whatever desires he may have for the balance of his life" ("Robert Moran's Monument").

Rosario

Moran and his family moved into the Newhall house on Orcas in the summer of 1906. He hired an architect to design a permanent residence but he threw out the plans (for a two-story frame house) and came up with his own. His retirement home would be a five-level, 54-room mansion, sited inside a sheltering point on Cascade Bay, oriented to command a view of the water. He called it Rosario, after the strait lying between the San Juan Islands and the mainland.

Moran approached the building of Rosario with the same thoroughness he had applied to his business. He set up a woodworking plant, brass works, and machine shops on site; hired the best craftsmen, many of whom were shipwrights or machinists who had once worked for the Moran Brothers Company; and imported the finest materials, including plate glass from Belgium for the windows; teak from India for the floors, and mahogany from Honduras for woodwork and furniture. He dammed one of the lakes and built a hydroelectric power system to supply electricity to the shops and later to the mansion.

Moran's oldest son, John, served as construction foreman, but Moran oversaw every detail, down to the door hinges. Several hundred mahogany doors were installed in the mansion, each one so solid and heavy that they needed special hinges to open and close smoothly. Moran designed bronze "butterfly" hinges with pins of self-lubricating lignum vitae, a hardwood often used by shipbuilders. He incorporated many other nautical touches in the mansion, including built-in ship's bunks in some of the bedrooms. He strung anchor chain salvaged from the Nebraska (the chain had broken in two during an engine test run in 1906) around the entrance circle outside. On the grounds, overlooking the bay, he installed a figurehead from an old clipper ship. He painted the exterior of the mansion with the same deep maroon paint used on ship bottoms. (A subsequent owner painted it white.)

The mansion was built to last, on bedrock, with walls 12 inches thick and six tons of copper sheeting on the roof. It was also built to accommodate crowds. There were 18 bedrooms, in addition to a dormitory in the attic that could sleep up to 50 on cots. An avid photographer, Moran put a darkroom on the third floor. There was a tiled swimming pool in the basement, along with a two-lane bowling alley and a game room with billiard and pool tables. The mansion's most outstanding feature, and Moran's special pride, was a soaring, two-level music room, equipped with a Steinway grand piano and the first pipe organ in the Northwest. Made by the Aeolian Company in New York City, the organ's 1,972 pipes were hidden behind a façade of artificial pipes carved from mahogany. The console was placed in a horseshoe-shaped balcony above the main floor of the music room. Moran liked to entertain his guests by sitting at the console, his back visible only from the waist up, moving his arms in a way that suggested he was playing the organ. It was actually an automatic or "player" organ; like a player piano, it operated on music rolls. (The console has since been rebuilt to include a keyboard for manual operation.)

The family moved into the mansion on June 21, 1909. Melissa Moran wrote the first entry in the guest register: "We moved in this house this day." Robert Moran made the second entry: "A House built on a Rock" ("Moran Mansion Centennial").

Moran State Park

Moran once said he was "born primarily a constructor" ("Robt. Moran ..."). He liked building things. At Rosario, in addition to the mansion, he built a circular concrete "playhouse" with a fully equipped kitchen, a kiln, and other amenities for his children; a total of five bungalows and cottages for his cooks, gardeners, and maids (he did not allow the domestic staff to live in the mansion); and two identical houses, side by side, for his brothers Frank and Sherman and their families. He was proud that "No architect or technical adviser can make any claim on what has been created by me on this island" ("Robt. Moran ...").

He also built a yacht, a three-masted, 132-foot schooner named the Sanwan. "Ever since Robert Moran has occupied his home at Rosario he has been very busy making improvements and alterations," the San Juan Islander reported in September 1912. "Last fall, however, he looked around and could find nothing more to do. And so he decided to build a yacht" ("Moran's New Boat"). He invited 400 guests from Seattle to celebrate the launching of the Sanwan in 1917 and said he planned to take it on long, lazy ocean voyages. But he lost interest after just a few short trips. "When I planned and constructed the vessel, I thought it would be fine to go cruising over the waters of the world, but when she was finished, I found that my yacht building plans were a mistaken idea" (Moran, 25).

Moran was still working on the yacht when he began exploring the idea of donating some of his land to the state for the creation of a public park. He had been interested in preservation since his days as a young engineer on the Alaska run, when he met John Muir. He did not permit hunting or logging on his property. No trees were cut for firewood; only driftwood was burned in the estate's many fireplaces. He often placed ads in local newspapers reminding hunters to stay away. "I am the owner of a large portion of the east end of Orcas Island, including lands surrounding the lakes," he noted in a typical ad. "My purpose is to preserve the deer and other game. There is no public land to hunt over and all are trespassers who come here for that purpose" ("Notice to Hunters").

Moran initially proposed donating only a small, 80-acre parcel near the summit of Mount Constitution but soon expanded the offer. In 1911 he offered to give the state 3,000 acres, including most of the mountain, provided the state buy some of the adjacent land. The suggestion may have come from his close friend Edmond S. Meany (1862-1935), a University of Washington history professor, a lecturer in forestry, and president of the Washington Mountaineers Club. The state declined: it had neither an agency that could accept such a park nor funds to manage it. The legislature created a State Board of Park Commissioners in 1913 but gave it no funding. Moran trimmed the size of his proposed donation to 2,731 acres and eliminated the conditions. Finally, in 1921, the state accepted his offer and created Moran State Park.

Over the next decade, Moran added another thousand acres to the park and used his own money to pay for the vast majority of improvements, including trails, roads, and bridges (naming one the Paul Bridge in honor of his late brother). He pressed the legislature to replace the wagon road that he had built to the top of Mount Constitution with an "auto road," and recruited prominent people from all over the state to help him lobby for it. In 1925 he wrote to Meany:

"We are getting important people here and up the mountain and they all without exception put that view second to none. I feel that this road will make the Moran State Park the most visited in the state and I also feel that if the road is not built in my lifetime, it may never be built" (Special Collections).

He built a grand gateway arch over the main entry to the park and put on it a bronze plaque: "Moran State Park dedicated to the state of Washington by Robert Moran July 16, 1921 for your pleasure and care. No killing or fires." (The arch has since been rebuilt, but the plaque remains.)

Selling Rosario

Moran's wife of 51 years, Melissa, died of cancer at Providence Hospital in Seattle on November 20, 1932. By that point, he had outlived all of his brothers and sisters. None of his children had the interest or the financial ability to take over what was left of the estate. Moran put it on the market, emphasizing the fact that he wanted it to be maintained as a whole, rather than divided into small holdings. He promoted it by publishing a booklet titled "Rosario: An Estate in the Pacific Northwest," with photographs by noted photographer Asahel Curtis (1874-1941). The booklet was distributed to real estate agents in major cities all across the country. He also took out large ads in National Geographic Magazine and Fortune, describing Rosario as "A Sea-Girt Arcadia in an Evergreen State." But it was the depths of the Great Depression and no potential buyers surfaced. Moran lowered the asking price, to $150,000, and took out a new round of ads in 1937 and 1938. Selling points included the fact that the mansion had "a burglar-proof vault with two manganese time-lock safes" and the overall property was "a safe retreat from future economic turmoil" ("For Sale").

Rosario was finally sold in October 1938 to Donald L. Rheem, a California industrialist. The purchase included 1,339 acres of land, the mansion and all its furniture (including the organ and the Steinway), the twin houses that Moran had built for his brothers, four houses that had been built for the domestic staff, a three-story barn, and the perpetual and exclusive use of hydroelectric power from the lakes in Moran State Park. The price was a reported $50,000 -- "Undoubtedly one of the biggest real estate bargains in our state's history," as Seattle Times columnist Walt Evans pointed out in 1981 ("Orcas Retreat"). (Rosario was converted into a resort in 1960 and listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977. Moran's hydroelectric plant still supplies it with power.)

Moran built a modest house at White Beach, near the ferry landing on the southwest side of Orcas Island, and moved into it with his daughter Nellie. When a Bellingham newspaper reported that he had sold his "palatial home" and was living in a "shack," he offered a gentle rebuttal: "I have as good a bed and other conveniences, and sleep probably better than I did at Rosario." Then he added this:

"But the best of it all is that I am so constituted that it would be no burden for me to go back to life's conditions that were mine when I arrived in Seattle sixty-four years ago. Money represented no value to me excepting as a means to carry on an industrious life ... . When I had money that I could not use in an industrial and constructive way, I gave it away. I got my pleasure out of a simple personal life by industry" (Moran, 25).

He died in the house at White Beach on March 27, 1943, at age 86 -- about 40 years after doctors told him his lease on life was about to expire.