The Seattle Public Library's Ballard Branch Library No. 2 opened to the public on June 8, 1963, replacing a 1904 structure that had been paid for by steel baron Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919) and had served the Ballard community since before it was part of Seattle. Designed by Seattle architect Gudmund Berge (b. 1926), the second library reflected an overall Modernist style, modified by Nordic touches intended to honor the historical and enduring Scandinavian presence in Ballard. Located on 24th Avenue NW just north of Ballard's business district, the building served the community for more than 40 years before it too was replaced as part of the $196.4-million "Libraries for All" program approved by Seattle voters in 1998. The 1963 structure was determined to be eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places, and although it was demolished several years after its closure, its history has been thoroughly documented in writing and photographs for the benefit of future generations.

A Legacy of Libraries

Andrew Carnegie was a tight-fisted immigrant from Scotland who became enormously wealthy developing the American steel industry and at one time was considered the richest man in the world. He was an aggressive union-buster with a strong antipathy to the concerns of workers, but he ultimately helped give Americans of every class one of the greatest gifts of all -- free and unfettered access to the accumulated knowledge of the ages.

"The man who dies rich dies disgraced," Carnegie said on more than one occasion ("Andrew Carnegie"). No doubt with this in mind, he dedicated a significant portion of his wealth to funding construction of 1,689 public libraries across the length and breadth of the country, including seven that became part of The Seattle Public Library system. Carnegie's legacy is one of the most enduring philanthropic endeavors in American history, perhaps unmatched in the number of people directly and beneficially affected. More than 100 years on, his gift still gives -- in 2012 alone, more than 1.6 billion books and other media were borrowed from America's public libraries, many still housed in original Carnegie buildings that are at least a century old.

Ballard's Carnegie Free Public Library (1904-1963)

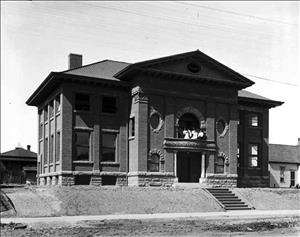

The Carnegie Free Public Library in Ballard, built with a $15,000 grant from the steel baron, opened in 1904 when the community north of Salmon Bay was still an independent town, populated in large part by people of Scandinavian origin. The sturdy Classic Revival structure of brick, stone, and terra cotta, located on today's Market Street, became the Ballard Branch of The Seattle Public Library in 1907 when Ballard voters approved annexation by their larger neighbor to the south. It was the city library system's first full-scale, purpose-built branch, and the original building was still standing in 2015, enshrined on the National Register of Historic Places since 1979.

The Carnegie Free Public Library was immediately popular and almost immediately inadequate. Starting with only 1,900 mostly donated volumes, by 1907 its collection had grown to 4,000 books. In 1910, a year that would see more than 56,500 "borrowings," the Ballard librarian complained that the building was already "outgrown" ("Days Numbered ..."). In 1932, its peak year, the Ballard Branch Library loaned out 282,000 volumes. Eight years later, in 1940, a study by Seattle's library board merely confirmed what the librarian had said 30 years before:

"Ballard. Oldest branch building, having been open to the public in 1904. Building now inadequate and impractical to enlarge. Serves an estimated population of 40,000; school enrollment, 4,614" (The People's University).

But it would be another 20 years before anything would be done. Seattle's citizens in the mid-twentieth century had shown a great fondness for libraries, tempered by a great reluctance to pay for them. In both 1950 and 1952, voters rejected ballot measures to finance new library construction. Finally, in March 1956, they relented and passed Proposition 2. It authorized $5 million in bond sales, primarily to finance a new Central Library.

When Proposition 2 passed, the actual cost of a new Central Library was not known; the $5 million was just an educated guess. The measure provided that if there was anything left over, it would go to building new branch libraries, including, at long last, one to serve Ballard. There were no guarantees, but in November 1958 the city council's finance committee was predicting a $500,000 surplus, which proved remarkably accurate.

The Ballard Branch Library No. 2 (1963-2005)

Seattle's new Central Library was dedicated on March 26, 1960, just days more than four years after voters passed Proposition 2. Located downtown on 4th Avenue, the building enclosed 206,000 square feet and cost $4.5 million to complete. This, as predicted, left $500,000 available for new branch libraries, and Ballard was at or near the top of the list, together with Magnolia and a planned Southwest Branch in underserved West Seattle. On February 9, 1961, Seattle planning commissioners directed their staff to start looking for potential sites in Ballard.

A project architect was named even before a site was found. Ballard residents were proud of and held tight to their Scandinavian heritage, and they must have been pleased on April 18, 1961, when the library board announced that it had awarded the architectural and engineering work to a Seattle partnership, Mandeville and Berge. The project's lead architect had a formidably Norwegian name -- Gudmund Brynulf Berge (b. 1926). He and his partner, Gilbert Mandeville (1910-1996), had opened for business only four years earlier, in 1957, but they made their mark early with the design for the Logan Building in downtown Seattle. Completed in 1959, the 10-story structure at 500 Union Street was the city's first example of aluminum and glass curtain-wall construction, and its first International Style building.

Ten days after awarding the design and engineering contract to Mandeville and Berge, the planning commission recommended to the library board that the new facility be built on the northern periphery of the Ballard business district, and later submitted a list of potential locations. In July 1961 the library board selected a site, and on September 20, almost exactly six months after the architects were named, the land purchase was announced to the public.

The new library and its parking lot would be located on the west side of 24th Avenue NW between NW 57th and NW 58th streets. The purchase price for the land was $70,000 and, as the planning commission had recommended, the location was just two blocks north of Ballard's main business district. The announcement also gave the public its first vague hint of what would be built there: "Mandeville and Berge, architect, will design a 7,000-square-foot building for the 20,000-square-foot site" ("Ballard Library Site Purchased").

Building contractors could not prepare bids until the plans and specifications were substantially complete. Berge went right to work, but the design phase would take more than a year, and bidding did not begin until the late summer of 1962. On October 15 that year the library board announced that the winning bid, for $161,646, had been submitted by Strand Incorporated, a Seattle firm established in 1954. Construction was to begin within 30 days and be completed within 180 days. The announcement stated, "The library will have 6625 square feet of space on the main floor and 500 square feet of storage in the basement" ("Board Accepts New Ballard Library Bid"). Another local company, Interiors Northwest, provided the low bid for furnishings, at $6,312.

More details were revealed that day, some of them correct. The city's chief librarian, Willard O. Youngs (1910-1993), predicted that the total cost of the project, including landscaping, would be about $200,000. Two pieces of public art were announced for the building -- an outdoor fountain and pool by sculptor Howard Dallas Duell (1929-2009) and "an outdoor mural" by Archie Graber (1924-1984) ("Board Accepts ..."). The last item was wrong; Graber's contribution would not be an outdoor mural, but rather a graceful wood sculpture that would hang in the building's lobby over the main circulation desk. Although it wasn't announced that day, the contract for landscaping was awarded to a noted Modernist landscape architect, Robert Chittock.

As was probably hoped for and expected, Gudmund Berge brought a Scandinavian sensibility to his design of the new library. The Nordic influence was very apparent in the finished project, as summarized in a 2015 report prepared by Sheridan Consulting Group of Seattle:

"The Modernist building reflects the Scandinavian heritage of the Ballard neighborhood and its designer, Gudmund Berge. When it opened, the library was described as '... a spacious, high-ceilinged building with a sturdy design and rugged materials evocative of the Scandinavian tradition of the area.' Cedar shingles, upon which Ballard's economy had once been based, were used for the roof. The two prominent copper-clad beams along the gable turn upward at the ends to evoke the 'dragon style' roofs seen in late-19th century Scandinavia. The form and details also exhibit the influence of vernacular farm houses of southern Scandinavia" ("Ballard Branch ... Building Documentation")

From the Outside

The entire site faced east from the west side of 24th Avenue NW and spanned the length of the block between NW 57th and NW 58th streets. The library building occupied the northern portion of the property, with a generous parking lot, a relatively rare amenity for branch libraries in Seattle, taking up the southern part. The building was a single story built on a concrete slab, but with a small partial basement excavated beneath the staff area. The library's footprint measured approximately 120 feet by 65 feet, and although the roof when viewed from above formed a rectangle, the outline of the building beneath did not.

Viewed from the front, the exterior featured a series of seven stone-faced pillars arrayed along its length at approximately 20-foot intervals. In Scandinavian style, each of these pillars was notched at the top to provide a secure resting place for the roof's laminated-wood rafters, which in turn supported a single-gabled roof that ran the full length of the structure. At three of the building's corners and at the entryway, these pillars were extended inward to create partial walls of stone. Additional roof support was provided by steel beams placed in the interior, where they also provided support for shelving in the public reading rooms.

The northern half of the library housed the open stacks and the adult and children's reading rooms, measured approximately 60 feet in length, and occupied the building's full width of approximately 65 feet. The children's area faced 24th Avenue NW, and here the lower part of the front façade was covered with a stucco-like coating, above which were tall glass windows set in aluminum frames that extended to the underside of the roof. The roof extended slightly past the wall at this location to form a shallow eave. The rafter tails extended beyond the eave, ending in decorative notchings that had origins in Nordic design.

Adjacent and to the south of the reading rooms was the lobby, and here the building's front façade was indented eight feet. A vestibule enclosed in thick glass from floor to roof on three sides offered entry to the building. The fourth, north wall of the vestibule was formed by the extension of the adjacent stone-faced pillar. The lobby contained casual seating and, on its south side, the main circulation desk, which also marked the division between public and staff areas.

The portion of the building to the south of the glassed-in vestibule was indented an additional six feet and maintained that configuration for 39 feet to the building's southern end. The roof, however, remained of uniform width along its entire length, providing cover for a walkway and ramp that led from the parking lot to the entrance vestibule.

The wall at the north end was coated, up to about seven feet, with the none-too-attractive stucco-like material, but it was topped by tall windows that extended to the peak of the roof and provided ample natural light for the adult and children's reading rooms. At the library's south end, facing the parking lot, the stone-clad pillars at the corners were extended inward to form partial walls, with the remaining space between them covered in the same stucco-like material, relieved only by three smallish windows set high in the wall.

In the building's rear, at the north end, a narrow space between it and the property line provided a small courtyard for outdoor reading, and this was the site of Howard Duell's fountain and pool installation, entitled Of Sea and Life. To the south of that space in the building's rear was a private, fenced-off courtyard for the use of library employees.

Looking Up

The part of the building that perhaps reflected most clearly Ballard's ethnic and commercial history was the roof. It was covered with cedar shingles, a nod to the many cedar mills that once lined the shores of Salmon Bay, dangerous places where generations of Scandinavians had found jobs and, all too often, lost digits.

The roof sloped up on either side to a single peak, and near the top two heavy ridgepoles clad in copper ran the entire length of the building, one on either side of the peak and about three feet apart. Above the library's public areas, including the lobby, the space between these two beams was covered with a clear skylight, bringing in additional natural illumination. The total length of the skylight was nearly 80 feet. The two copper-clad beams extended beyond the ends of the building, their bottom halves scalloped "in a Norse-like fashion" ("Ballard Library, Landmark Nomination")

On the Inside

Patrons entering the library through the glass vestibule on 24th Avenue NW would turn right to access the public reading rooms, which took up most of the north half of the building. Here windows on three sides provided ample light. Shelving around the room's perimeter was equal in height to the exterior stuccoed walls, leaving the windows above unobstructed. The children's area and the adjacent adult reading room were separated by shelving secured to the building's interior steel roof supports. Furnishings and other details of the children's area were scaled for use by small patrons.

The ceilings throughout the building were acoustical tile and the floor was covered with vinyl linoleum. Supplementary artificial light in the public areas was provided by fluorescent lighting concealed in wooden coves atop the shelving that ran around the reading rooms' interior walls. With the growing use of computers and other electrical devices, it was necessary over the years to add additional wiring housed in surface-mounted conduit.

In the space between the public and staff areas, the lobby extended the width of the building and featured casual seating and racks to hold periodicals. Above the main circulation desk hung Archie Graber's graceful wood sculpture, Tree of Knowledge. Beyond this, in the building's south half, were library staff areas, including an approximately 900-square-foot partial basement divided between a work area and a mechanical/electrical room.

The Library and the Community

The official dedication of Ballard Branch Library No. 2 took place on the evening of Friday, June 7, 1963, and the doors were scheduled to open to the public the next day. Among the honored guests were the architect, Gudmund Berge, and several living descendants of those who had donated books or money in 1904, their identification made possible by meticulous records kept by the Carnegie's first librarians.

A special presence at the affair was Blanche Dunmore (1874-1971), a retired teacher and school librarian who in 1904 had helped lead a student drive to obtain books and then stocked the first shelves with volumes that had been donated or purchased with donated funds. As an article in The Seattle Times noted:

"Blanche Dunmore and others like her never could have guessed that this day would arrive when books for everyone in Ballard would be available in quantity and quality, thanks to the dedicated librarians and the citizens of Seattle who taxed themselves for a building in a day when Andrew Carnegie no longer exists" ("Old Library Replaced ...").

Public libraries, at least in Seattle, evolved into more than just repositories for books and other media. They also served in other ways, becoming community centers of a sort and providing space for public events. These included book and poetry readings; musical performances; seminars offering free tax, employment, and investment advice; and special programs for children and toddlers. The first such event at the new Ballard Branch Library was a book review and coffee hour held on July 10, 1963, with admission free to all. There would be hundreds more open events over the library's 41-year working life.

Gone But Not Forgotten

It is perhaps ironic that Andrew Carnegie's gift to Ballard still looms on Market Street, protected as a City of Seattle landmark in 2013, while the Ballard Branch Library No. 2 that is the subject of this essay has disappeared. In 1998 Seattle voters again put their money up, approving the $196.4-million "Libraries for All" bond proposal, a sum that would have given even Carnegie pause. On May 14, 2005, the new Ballard Branch Library No. 3, at 5614 22nd Avenue NW, threw open its doors for the first time. Its predecessor had cost about $215,000, including furnishings; the new facility came in at a whopping $10.9 million.

In its last year, the "old" Ballard Branch No. 2 had checked out more than 683,300 books and other materials, the most of any neighborhood branch in the city. It stayed open until the very end, closing its doors only when the new library was ready to accept transfer of its holdings. The Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation determined that the building was eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places, alongside its Carnegie predecessor. Although it has since been demolished to make way for new construction, the history of Seattle's Ballard Branch Library No. 2 is being preserved for future generations.