Helen Sommers was elected as a Democrat in November 1972 to represent Seattle's 36th District in the state House of Representatives. She won re-election 17 consecutive times over the next 36 years, was a tireless advocate on issues important to women, a steadfast friend of higher education, and an expert on complex budget, finance, and pension matters. Her no-nonsense approach and ability to resist political pressure earned her widespread respect, if not universal affection. Citing her age (76) and diminished capacity for the legislative grind, Sommers retired after the 2008 session. By then, she had served longer in the House of Representatives than anyone except the legendary John L. O'Brien (1911-2007).

An Adventuresome Young Woman

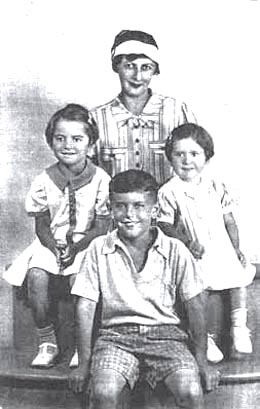

Helen Elizabeth Sommers was born on March 29, 1932, the middle of three children of Roy (1897-?) and Christine Sommers (1901-?). She spent her childhood in Woodbury, Gloucester County, New Jersey, together with her older brother Martin (1927-2006) and younger sister Joan (b. 1935). Her father had owned his own automobile dealership in the 1920s, but lost it during Great Depression and subsequently earned his living selling cars for others. Her mother had left a secretarial job to raise the children, but the economic hard times forced her back to work.

Sommers attended Woodbury High School and like many young women of that era she focused her studies on secretarial training, but she was also a voracious reader and a member of the National Honor Society. After graduation Sommers went to work as a clerk for a Mobil Oil Company refinery near her New Jersey birthplace. In 1954 she was transferred to Mobil's operations in Caracas, Venezuela, where in 1958 she married a Cuban/Panamanian businessman, Mario Selles. They would remain together for seven years before divorcing.

Sommers would live and work for Mobil in Caracas for 14 years, becoming a fluent Spanish speaker and immersing herself in Venezuelan culture. In 1962, at the suggestion of a coworker, Sommers began taking correspondence courses from the University of Washington, although she had never been anywhere near the Northwest. In 1965 she traveled to Seattle to take summer classes at the university and fell in love with both the school and the city. Sommers returned for another summer at the UW, then decided to move to Seattle in 1968 "to begin a new life" (Sommers Oral History, p. 12).

The New Life

Once settled, Sommers enrolled again at the university and went on to earn both a bachelor's and a master's degree in economics. A self-described born feminist, she was galvanized into activism by Betty Friedan's The Feminine Mystique, became involved with the city's League of Women Voters, and was an early member of the nascent Seattle-King County chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW).

In 1970 and 1971, while teaching economics at Edmonds Community College, Sommers appeared frequently on panels discussing economic discrimination against women, including inequities in the state's community-property laws. She was becoming known as a persuasive advocate for women's issues, and in early 1971 she was elected president of the local NOW chapter. In April of that year Seattle Mayor Wes Uhlman (b. 1935) appointed her to a seat on the Seattle Women's Commission, which he had established to promote and enhance the role of women in civic affairs. A local newspaper said of her at the time: "Mrs. Sommers ... has been active in the past year speaking, lobbying, talking with women, working toward raising women's aspirations" ("Women's Commission: Who Are They?"). Within just three years of her arrival in Seattle to stay, Helen Sommers had become a figure of some influence and no small ambition.

In January 1972 Sommers traded her teaching job for a position as an analyst and assistant to Lee Kraft (b. 1935), King County Council's first administrator. She found a political mentor on the council in Democrat Bernice Stern (1916-2007). Five months later, Sommers was named the first president of the new Washington State Association of the National Organization for Women and was appointed to the committee campaigning for the Washington state passage of the Equal Rights Amendment. In another sign of her growing reputation and influence, Republican Governor Dan Evans (1925-2024) appointed Sommers to serve on a committee he established to study tax reform.

A Political Plunge

The Republican Party dominated Seattle politics between the end of World War II and the early 1970s. The city's 36th legislative district, which in 1972 encompassed Magnolia, Queen Anne Hill, Belltown, and parts of Capitol Hill and downtown, had long been an impregnable GOP bastion. From 1944 until 1972, not a single Democrat was elected to represent either of the two 36th District positions in the state House of Representatives. Then Helen Sommers, barely four years in Seattle, announced in August 1972 that she would run for the Position 1 seat held by Republican Gladys Kirk (1903-1974), who had been appointed in 1956 to a seat vacated by her husband's retirement and was the senior woman in the legislature, in both age and tenure. As Sommers explained years later, "with the supporters of NOW, the League of Women Voters, encouragement from Bernice Stern, the 36th District Democrats, and also some legislators, I decided to go for it!" (Sommers Oral History, p. 15).

Kirk had an opponent from her own party in the primary, but Sommers, perhaps because few Democrats thought the seat winnable, had none. While Kirk was still fighting off GOP challenger David Rohrbaugh (1936-2012), Sommers began an energetic campaign to unseat her. When the primary votes were counted on September 19, 1972, Kirk had won, and the two Republicans had together garnered more than twice as many votes as the newcomer Democrat. But within less than a month, Kirk was worried, telling a local newspaper, "You know, the district is changing" ("36th's Campaign Heats Up").

Kirk was right to be concerned. The state Equal Rights Amendment was on the ballot and enjoyed wide support among Democrats, a sure draw for a good turnout. Redistricting had added areas of Capitol Hill and downtown to the 36th, bringing to it a more liberal group of potential voters. Sommers campaigned vigorously, calling on homes and apartments throughout the district's 109 precincts. She had doors slammed in her face and was bitten by a dog (party affiliation unknown), but steadily gathered supporters and endorsements.

The local press did not seem quite sure what to make of Sommers, describing her with some condescension as "diminutive (5 feet 2 inches), in her chic pants suits," but adding, with a measure of rather awkward respect,

"Ms. Sommers (the 'Miz' reflects her commitment to the feminist movement in which she says she plays a conservative — as opposed to militant — role), is bright, intense, and carries impressive credentials" ("36th's Campaign Heats Up").

Playing on the long unbroken history of Republican representation, Sommers's campaign mantra was "Let's return the 36th District to the two-party system" ("36th Campaign Heats Up"). She earned an "outstanding" rating from the Municipal League to Kirk's merely "good," and when the ballots were counted on Election Day, Sommers had comfortably won, collecting 12,787 votes to Kirk's 10,366. And, after trailing in the polls until the last absentee ballots were counted three weeks after election day, the ERA referendum squeaked through by slightly more than one-fourth of 1 percent statewide and was added as Article XXXI of the state constitution.

Securing the Seat

When Sommers arrived in Olympia for the 1973 legislative session she was one of only 12 women in the 98-member House of Representatives. Democrats held comfortably majorities in both the House and the Senate after enduring three consecutive sessions in the minority.

Sommers spent much of the 1973 and 1975 sessions grappling with unglamorous and arcane problems plaguing the state's public-pension system (the legislature regularly met only every two years until a constitutional amendment providing for annual sessions became effective in 1980). Her constituents were clearly pleased with her performance; she won reelection in 1974 with more than twice the votes of her Republican opponent. But in 1976 she faced a more formidable threat. Ken Eikenberry (b. 1932) had represented the 36th District's Position 2 for three terms. Declaring that "This district is not big enough for both of us," he announced that he was going to give up what was considered a safe seat and try to oust Sommers from Position 1 (Sommers Oral History, p. 19). Sommers pointed out, with unassailable logic, that the district clearly was big enough, since the voters had elected them both.

A major issue in the campaign was pension reform. Sommers had helped craft a bill to address the system's longstanding problems, a measure that Eikenberry, unexpectedly, had voted against in the 1975 session. That vote may have proved decisive in the election, and when the ballots were counted, 53 percent of them went to Sommers. A more cooperative Republican, Joe Taller (a future director of the state's Office of Financial Management), won Eikenberry's abandoned Position 2 seat, and in the 1977 legislative session a pension-reform bill was passed. Eikenberry stayed in politics and would go on to serve as Washington's attorney general for 12 years. In 1992 he narrowly lost the gubernatorial election to Democrat Mike Lowry (b. 1939).

Serious Business

Helen Sommers's early years in the legislature coincided with developments that would transform the body. It had since statehood been a semi-annual gathering of mostly men that largely limited itself to approving or disapproving the sitting governor's proposals. It was soon to become more independent, a demonstrably equal law-making branch of government that met every year and had increasing numbers of women members. Republican Dan Evans, who served three terms as governor from 1965 to 1977, realized the need for an annual legislature and regularly called special sessions during off years, most often to make adjustments to the biennial budget passed the previous year. Under the leadership of House speaker Leonard Sawyer (b. 1925), legislators in Sommers's inaugural session were for the first time given full-time professional staff, providing some continuity and enhancing institutional memory between sessions. Sawyer that same year appointed Sommers vice-chair of the House revenue committee, an unusual honor for a new member and a recognition of her expertise in financial matters.

But trouble was brewing. The House was very much still a boys' club and an old-boys' club at that. Sawyer was not widely liked, even among many members of the Democratic caucus, and he was dogged by rather vague allegations of corruption. Newer members from his party bristled at Sawyer's expectation that they would vote according to his dictates, and Sommers soon would have a very difficult choice to make. A group that called itself "the backbenchers," rebelled, and on January 14, 1976, during a special session called by Governor Evans, it became clear that Sawyer would be forced from the speaker's chair if he didn't step down voluntarily. One of those doing the forcing was Sommers, and a journal entry she made a few days later depicted how wrenching it was:

"Just before the already difficult day began, one of the overhead high-powered television lights exploded and showered glass down on the House Chamber! We were already tense, but this small incident seemed to portend a day of exploding emotions. I remember thinking 'Ye gods! Leonard's world is crumbling around him, and he seems so unaware and so insensitive to the meaning of it all'" (Sommers Oral History, p. 29).

This was hardball politics, and despite Sawyer's early recognition of her talents, Sommers did not hesitate to do what she believed best served the Democratic Party and the legislature. As she explained matter-of-factly in a newsletter to her constituents: "Decision-making and responsibility (and thus power) have been spread from a single power-broker to several leaders and there is greater participation by more caucus members -- a healthier and more democratic structure" (Sommers Oral History, p. 30).

All Business

Sawyer's ouster was far from the last time Sommers would buck the Democratic establishment. In 1978 Ray Moore, a former Republican who had lost four previous attempts at elective office, announced that he would seek the single Senate seat for the 36th District, running as a Democrat. He later recalled how the party's leadership snubbed him:

"They're not happy with me because, having been a Republican, how could I possibly try to be a Democrat? They were antagonistic to me. But, unknown to me, it turned out I had one ally that was worth all of them, and that was Helen Sommers. After a rocky start, we got to be on the same frequency" (Moore Oral History, p. 60)

The "rocky start" Moore referred to was nothing unusual for Sommers. Throughout her political career she was all business, tightly focused, seemingly incapable of or unwilling to engage in small talk. She could be gruff and dismissive, but this didn't necessarily indicate animosity. Moore's experience upon first meeting her while running for the Senate is illustrative:

"I saw Helen Sommers. I walked over, and I said, 'Ms. Sommers, I'm Ray Moore.'

"She said, 'Yeah, I know.' Real friendly!

"So I said, 'Sometime, I'd like to get together with you and talk about the issues, so we're on the same frequency.'

"She said, 'Find your own issues,' and walked off.

"A few days later I got this little scrap of paper with half a dozen names on it with telephone numbers. It was signed, 'Call these — Helen.' So, I called them, and she'd already primed them. 'Yeah, we're with you, yeah, we'll take a yard sign, yeah, we'll have a coffee hour.' Every few days came another list" (Moore Oral History, p. 60)

Moore finally won a political contest, with Sommers's help. They became friends and were political allies until his resignation from the Senate in 1994.

The Glass Ceiling

Helen Sommers's election to the House in 1972 was not historic. With the exception of 1915, there was at least one woman representative serving in every House session since 1913. In 1943, with many men off fighting in World War II, the House had 12 female members, the same number as Sommers's first year in office. The state Senate was a somewhat different story. Between 1913 and 1975, only 26 women had served there, as opposed to a total of 184 having served in the House. In 1973, Sommers was joined as a representative by 11 other women, but the entire Senate remained male, the last year this was so.

Sommers's constituents could elect her time after time, but they could not give her the leadership positions in the House that many believed her credentials and work ethic deserved. She was widely recognized as one of the most, if not the most, knowledgeable legislators on revenue and budget matters, and no one worked harder. But she was a woman, and clearly was not a member of the glad-handing, backslapping, mostly male club that still dominated the House. Session after session the Democratic leadership appointed men to fill committee chairs that Sommers was more qualified to hold.

Her string of defeats must have been demoralizing. In 1980, with the House in a 49-to-49 tie, she tried and failed to become Democratic caucus chair. In 1981, with the Democrats in the minority, she made a late effort to become minority leader, and was again defeated. In 1982, after elections that put Democrats back in the majority for the 1983 session, she waged a campaign to become chair of the House Ways and Means Committee, but it was given to Representative Dan Grimm (b. 1945) of Puyallup, who was her junior in tenure and lacked her deep expertise in budget matters. A subsequent attempt to become majority leader in the House was also beaten back, with Grimm again besting her. Sommers recognized that both sexism and style stood in her way. "My style is different," she told a Seattle reporter.

"I don't operate on the basis of favors. If I don't like a bill, I won't change my mind just because someone really wants it ... . Clearly, I'm outspoken. And I'm impatient, too. But women aren't supposed to say strong things. They aren't supposed to be impatient'' ("Helen Sommers' Talents Wasted ...").

Some in her own party believed that Sommers's problem was more than just style. One Democratic colleague, choosing to remain anonymous, told The Seattle Times, "If there's a budget out there, she'll either work with the conservatives to screw it down tighter or she'll work with the liberals to boost the level -- just so she has a voice. She looks for every opportunity to be divisive'' ("Helen Sommers' Talents Wasted ..."). But her time was coming; her mix of liberal social views and relatively conservative fiscal policy was becoming mainstream, and her undeniable expertise in complex budget matters brought many colleagues to her door for guidance.

With perhaps more than a little schadenfreude, Sommers watched in the 1985 session as House Ways and Means chair Dan Grimm and fellow Democrat Jim McDermott, head of the analogous committee in the Senate, deadlocked over relatively small issues and were unable to agree on a budget. The party was looking increasingly dysfunctional, and younger Democrats (who some called "moderate conservatives" but who characterized themselves as "neo-liberals") were refusing to go along with the old-boy traditions of the legislature.

Sommers, who had been bucking the same system for well more than a decade, appeared to finally be coming into her own. The same year Grimm and McDermott deadlocked, she was appointed to head the Legislative Budget Committee, which sat in judgment of state-funded programs and agencies and recommended whether they should continue or be modified or terminated (a job that would lead her into conflict with the state ferry-workers' union, among other groups). But change in the internal politics of the legislature was slow in coming, and it would be nearly another decade before Sommers captured the one position she had coveted all along.

The "Decade of the Woman" Begins

Helen Sommers made another stab at election as House majority leader in 1986, but was defeated by Denny Heck (b. 1952). In a 1987 review of top legislators, The Seattle Times noted "Rep. Helen Sommers continues to have the brains to be top rank, but apparently not the personality to win leadership roles" ("A Guide to Influence"). Lingering sexism no doubt still played a role, but Sommers, indisputably smart and undeniably hardworking, remained her own worst enemy in the still-clubby atmosphere of Olympia politics.

The year 1992 was the biggest year for state Democrats since the Roosevelt landslide of 1936 and a flex point for women in politics. On the national level, Bill Clinton (b. 1946), a centrist Democrat with much in common with Sommers, defeated incumbent President George H. W. Bush (1924-2018). Democrat Patty Murray (b. 1950) defeated Republican Rod Chandler (b. 1942) for one of the state's U.S. senate seats. All three Washington women who ran for seats in the U.S. House of Representatives won -- Democrats Maria Cantwell (b. 1958) and Jolene Unsoeld (b. 1931), and Republican Jennifer Dunn (1941-2007).

At the state level, Helen Sommers, running for the 11th time, trounced her Republican opponent, taking nearly 80 percent of the vote in the 36th District. And she was not alone -- women candidates won 38 House races and 12 Senate races, giving Washington the highest proportion of women legislators in the nation. In the statewide races it was almost all Democrats, and except for the governorship (won by Mike Lowry), almost all women -- Deborah Senn (b. 1949) ousted Republican Insurance Commissioner Richard Marquardt (1922-2012); Christine Gregoire (b. 1947), another Democrat and a future governor, won the state attorney-general race; Jennifer Belcher (b. 1944), a 10-year member of the House, defeated Republican Ann Anderson to become commissioner of public lands; and Democrat Judith Billings (b. 1940) was re-elected superintendent of public instruction. Eleanor Smeal (b. 1939), president of the Fund for the Feminist Majority, was exultant:

"Women have really cracked the political glass ceiling. It's what we've been waiting for. This isn't going to be the 'Year of the Woman.' It's going to be the 'Decade of the Woman'" ("Democrats' Day — From White House to State ... ").

Clearly the public had come to accept, and in many instances prefer, women holding positions of political power. The question for Sommers, as it had been for 20 years, was whether her colleagues in government would equally see the light.

Finally Gained, Quickly Lost, Gained Again

In many ways, Helen Sommers and her one-time colleague, then-Representative Gary Locke (b. 1950), were kindred spirits, and they worked together well. Both were policy wonks through and through and both had the smarts and the patience to deal with the minute details of budgets and revenues, striving against impossible odds to make the latter sufficient to fund the former. Over the years, Sommers had chaired several House committees, including the State Government Committee and the Revenue, Higher Education, and Capital Budget committees. But the position she always wanted most was to head the powerful Ways and Means Committee, which was responsible for just what its name indicated -- largely through setting tax policy, the committee was charged with finding the ways and means of financing government operations and programs.

Democrat Joe King was speaker of the House from 1986 to 1992, years that the Democrats had comfortable margins in both chambers of the legislature. Sommers made no secret that she expected to get the job she had coveted for years. But King believed the Ways and Means Committee's mandate was too broad for complicated times, and he divided it into three -- appropriations, capital budget, and revenue. Sommers wanted to be chair of the Appropriations Committee, but in 1989 King gave it to Locke instead. Sommers's deep disappointment was tempered somewhat by her respect for and friendship with Locke, but it hurt nonetheless. House Chief Clerk Dean Foster, who served the legislature during many of Sommers's years there, would later say:

"I think that Helen internally and personally suffered a number of setbacks or defeats over the years. But she was always able to follow that by coming back and working with whoever had won out. She was always good at that because she put setbacks behind her faster than most people would" (Sommers Oral History, p. 166).

Things finally seemed to be going her way when in November of 1993 Locke was elected King County's executive and resigned mid-term from the House. Sommers was elevated to the chair of the Appropriations Committee in January 1994, her long-held ambition fulfilled at last. Her way was perhaps made smoother by improved relations with her colleagues:

"By her own measure, Sommers, 61, has had 'the rough edges beaten off me' in several failed attempts to win leadership posts. Colleagues say she spends more time cajoling and soliciting their ideas, less time skewering them with figures and policy arguments. And she laughs more" ("After Two Decades, Helen Sommers Rises to Prominence ...").

Victory was sweet but short; in the elections held later that year, Republicans captured the House, winning 62 seats to the Democrats 36. After less than a year as chair of appropriations, Sommers was now just the ranking minority member on the committee. Democratic voters had kept Sommers in office for 22 years before the party leadership gave her what she and others had long considered her due. After only one year, Republican voters had snatched it away. Republicans would retain control of the House from 1995 through 1998, and Sommers waited, more or less patiently, for her turn to come around again.

In 1999, 2000, and 2001 the House was evenly divided, 49 to 49, and Sommers was halfway back, sharing the chair of the Appropriations Committee, uneasily, with Republicans. In 2002 the Democrats wrested back a razor-thin majority of 50 to 48 in the House, and she again took sole possession. The Democrats increased their margin in the House for the next two election cycles, and Sommers kept the appropriations chair that she had fought so long to capture and which so closely fit her expertise.

Thirty-six in the 36th

By early 2008 Helen Sommers, by then the state's longest-serving sitting legislator at 36 years, was giving a few hints that her time in Olympia might be coming to an end, including returning to donors some political contributions. Nonetheless, she remained as prickly as ever when other Democrats started cautiously campaigning for her seat. "I am 75," she told The Seattle Times. "I was thinking about it [retirement] last year, and I'm still thinking about it. But when they push me, then I'll push back" ("Will Legislative Veteran Hang in There?"). The rumors were true, however, and in March of that year Sommers told the press, "To say you're retiring during the session doesn't seem like the wise thing to do. I tried to keep it until after session but it leaked out." When asked what she would do after stepping down, she replied, ""What am I going to do? I'm going to take it easy" ("Sommers to Leave Legislature ...").

For nearly two hours of the last day of the 2008 legislative session, members of both the House and the Senate paid tribute to Sommers. Republican Representative Bill Hinkle of Cle Elum opined that the House "would never be the same" without her. The speaker of the house, Democrat Frank Chopp, who had not always gotten along with Sommers, told her, "Millions owe you a debt of gratitude" ("In Olympia, Inaction Was Part Of Game Plan ..."). Sommers, her penchant for terseness intact, spoke for barely more than a minute, graciously bidding her colleagues farewell from the floor.

A Summing Up

During her 36 years in the legislature Helen Sommers earned recognition as an expert on fiscal matters and a steadfast supporter of higher education. Starting with her early efforts to rein in the State's archaic and abused public-pension system, she was a constant and reliable critic of government waste and excess. The one area of the budget that to her was sacrosanct was higher education, and she consistently strove to ensure that colleges and junior colleges received adequate funding, despite the condition of the overall economy. Her efforts in substantial part led to the establishment of branch campuses by both the University of Washington and Washington State University. Having earned her college degrees relatively late in life, Sommers tried to make it possible for displaced workers and homemakers to gain the economic advantages that come with higher education. She was also a consistent supporter of the rights of the elderly and the disabled, backing legislation that provided for state-funded respite for caregivers and tightening requirements for nursing homes. And, of course, every legislative session she labored, as a foot soldier or as a leader, on the complexities of the state budget.

There is little doubt that her brusque manner and intolerance for horse-trading were factors in the long years it took for Sommers to attain the leadership position that she was so eminently qualified to fill. On the other hand, those same qualities quickly disabused her male colleagues, in a time when women in politics were relatively few, of any suspicion or hope that she might be a pushover or swayed by flattery. From day one she was a force to be reckoned with and, just as importantly, to be respected, no matter what one's opinion of her personality might have been.

Throughout her career, and particularly during her years as chair of the House Appropriations Committee, Sommers was a hard sell when it came to funding other legislators' pet projects. Some said her favorite word was "no." Fellow Democrat Hans Dunshee (b. 1953) put it somewhat more diplomatically: "She'd say, 'Well, we'll consider it.' That meant you were dead" ("No-Nonsense Manner Served Legislator Well ..."). Her conservative views on most budgetary matters often earned her more respect among Republicans than among her fellow Democrats, and even though state spending increased dramatically during her years in Olympia, GOP deficit hawks were quick to say that it would have been much worse without her restraining influence.

Her independence sometimes cost her the support of groups traditionally allied to her party. Although Sommers was generally considered pro-labor, in 2004 the reliably Democratic Service Employees Union International (SEIU), angered by her failure to support its demands for wage increases, attempted to defeat Sommers in the primary by fielding a candidate, Alice Woldt, who was more sympathetic to their position. Despite the union spending more than $275,000 on Woldt's campaign, Sommers pulled out a narrow primary victory and went on to win the general election (her 16th) with nearly 80 percent of the vote.

As noted, Sommers's election in 1972 was not trailblazing; women had been serving in the House of Representatives in every session but one since 1913, and 11 others were elected in her debut year. But her widely recognized competence, work ethic, and serious-mindedness surely encouraged the steady growth in the number of women members in the House that began the year she took office. In her first 22 years in the legislature, that membership well more than tripled, from 12 in 1972 to 40 (nearly 40 percent) in 1994. A good argument can be made that Sommers's performance over the years helped convince male legislators that women could be just as effective as they believed themselves to be. She set an example, many women followed, and several went on to win office at both the state and federal levels. During her long years in Olympia, Sommers did much to solidify women's rightful place as full participants in the serious business of governing, and this is perhaps her greatest single contribution to her adoptive state.

Helen Sommers died on March 7, 2017, at the age of 84.