On April 28, 1919, the office of Seattle mayor Ole Hanson (1874-1940) receives a bomb in a package sent from New York City and addressed to the mayor. Hanson is not in the office that day and the package is opened by a clerk. Fortunately, he is holding the package upside down and the bomb fails to explode. The bomb turns out to be part of a larger anarchist plot to attack politicians and well-known businessmen throughout the United States on and around May Day. At least 36 bombs are eventually discovered throughout the country.

Paranoid Backdrop

The end of World War I in November 1918 did not bring the peace that so many hoped for. As 1919 dawned, revolutions were ongoing in Europe and insurrections were igniting elsewhere, while in the United States tensions between management and labor were boiling. In numerous American cities that year strikes large and small broke out, some of which became violent and ended with fatalities. At the same time, communist-leaning anarchists, many of whom were believed to be associated with the radical labor union Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or Wobblies) wreaked havoc by planting and mailing dozens of bombs throughout the country. Fear of communism, often called Bolshevism in 1919, brought on a "Red Scare" that was every bit as intense in 1919 America as it was during the more well-known McCarthy era of the early 1950s.

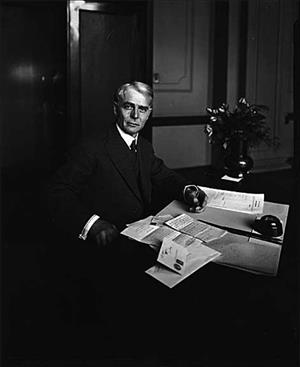

It was against this increasingly paranoid backdrop that America's first general strike took place in February 1919 in Seattle. It fizzled out after five days, and a new hero arose: Mayor Ole Hanson, a former realtor who had been elected mayor the preceding March. During the strike he threatened to impose martial law (he actually didn't have the authority), issued a proclamation declaring that "the anarchists in this community shall not rule its affairs" ("Proclamation"), and called more than a thousand army troops from Camp Lewis (later named Fort Lewis) into the city. Though the strike likely would have failed without his intervention, many nonetheless saw his aggressive posturing as stopping a Bolshevik revolution in its tracks. Near-universal praise from across the country swept into Seattle, but the attention also apparently made Hanson the target of a determined group of radicals.

Upside Down

On April 28, 1919, Hanson was in Colorado on a Victory Liberty Loan speaking tour, part of the country's final effort to sell bonds to cover the costs of World War I. That morning, an innocuous-looking package bearing the return address of Gimbel Brothers, a department store in New York City, arrived in the mayor's office. Hanson's regular secretary, G. A. Conklin, was with the mayor, and M. H. Strouse, chief clerk in the city's building department, had been drafted as the mayor's acting secretary. Strouse opened the package's wrapper and found a small box; opening that, he found a roughly six-inch-long, inch-and-a-half-diameter wooden tube with a cap on the end. He casually attempted to open the cap, but it stuck. Holding the tube cap-end down, he gave it a firmer tug and the cap broke. Liquid (some type of acid, though accounts of what type differ) streamed out and stung his hand. The startled Strouse saw several percussion caps and a small glass vial inside the tube and realized it might be a bomb, though at first he also thought it might be a joke.

Strouse was fortunate. He opened the wooden tube upside down, and the bomb failed to explode. It turned out that the wooden container was designed so the glass vial could not be removed without breaking it. Had Strouse been holding the tube right-side up when the vial broke, the acid would have flowed down the tube onto three percussion caps, exploding the caps and the powdered dynamite packed below.

The police were called. Word quickly spread and rumors flew even faster. The Seattle Times reported that the police had been notified of a sinister-sounding conversation overheard on a streetcar that the mayor would soon be "got" ("Chemists ..."). But the streetcar gossip only got part of the story. The plot wasn't against just Seattle's mayor. It was nationwide.

36 Bombs

The next day a bomb arrived at the Georgia home of former U.S. Senator Thomas Hardwick (1872-1944). The senator was out, but his wife and the family maid were home. Maude Hardwick opened the package but couldn't open the wooden tube inside it. She asked the maid to open the tube. The maid used a knife to force its top off, and when she did, the bomb exploded. The maid lost both of her hands and Mrs. Hardwick was also injured, though not as seriously.

Late that night an alert postal employee in New York City, Charles Caplan, read a newspaper account about the Hardwick bomb and the details of the package it was sent in. He realized he had 16 similar packages being held for insufficient postage in the parcel-postage storage room at the 30th Street and 8th Avenue post office. Warnings went out to every post office in the United States and Canada. More packages were found and some were intercepted. A few arrived at their destinations, but by this time the recipients knew better than to open them.

At least 36 bombs were eventually discovered, believed by authorities to have been the work of anarchists associated with the IWW as part of a strategy to wage "class war." The targets included U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (1841-1935), U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer (1872-1936), John D. Rockefeller Sr. (1839-1937), and J. P. Morgan Jr. (1867-1943).

Hanging Places

Hanson continued his speaking tour. The New York Times covered his May 1 appearance in Kansas before the Topeka Chamber of Commerce, remarking that he revealed "great emotion" when he said:

"I trust Washington will buck up and clean up and either hang or incarcerate for life all the anarchists in the country. If the Government doesn't clean them up I will. I'll give up my mayorship and start through the country. We will hold meetings and have hanging places" ("Hanson Warns America").

It was classic Hanson, except he wasn't joking about giving up his mayorship. He resigned as Seattle's mayor in August 1919, wrote the book Americanism Versus Bolshevism, and fished for the Republican presidential nomination in 1920. He didn't get it, but he quickly moved on. Hanson moved to California in 1921 and resumed his real-estate career, founding the city of San Clemente in 1925.