Seattle's King Street Station was built between 1904 and 1906 adjacent to reclaimed tideland south of the city's downtown. The imposing concrete, granite, and brick structure was financed by James J. Hill (1838-1916), who controlled both the Great Northern Railway that approached the city from the north and the Northern Pacific Railway Company that approached from the south. The station, located at the foot of King Street and bordered on the east by S Jackson Street, was the city's first elegant passenger depot and replaced an inadequate wooden structure built on Railroad Avenue after the Great Seattle Fire of 1889. In the middle decades of the twentieth century ill-considered and poorly executed "modernizations" concealed or destroyed much of the depot's ornate interior detail and elegant ambience. In 2008 the City of Seattle purchased the property from the Burlington Northern & Santa Fe Railroad for $10 and began a long and costly process of restoring the grandeur of an earlier era. Five years and $56 million later, the renovated King Street Station was unveiled to the public, its original stately elegance largely recovered. It is now home to both Amtrak and Sound Transit's regional commuter trains.

Tacoma vs. Seattle

The Northern Pacific Railroad, which built the third transcontinental rail line to be completed and the first to reach Puget Sound, stunned Seattleites in 1873 when it chose Tacoma as its western terminus. Some of Seattle's most prominent business leaders responded the next year with the home-grown Seattle & Walla Railroad. Their first trains wouldn't run until 1877, the rails never got close to Walla Walla, and its cars carried almost nothing but coal, but the spunky 21-mile line made money and provided early evidence of Seattle's commercial potential.

When the Northern Pacific finally reached Tacoma in 1883, its tracks came up from Oregon and trains had to be barged across the Columbia River. By then it was becoming apparent to many that Tacoma had been the wrong choice. But the NP had invested millions around Commencement Bay and was loath to change its mind. The railroad's federal charter required it to provide service to Seattle, and from 1884 until mid-1887 it grudgingly operated a branch line north that was so poorly run that it was dubbed the "Orphan Road" (Armbruster). But its lack of faith in Tacoma's future was perhaps betrayed by the fact that the Northern Pacific made do there with a modest wood-frame passenger station, vastly less impressive than the ornate, Gilded Age depots that graced other terminal cities across the nation.

In 1887 the NP's tracks finally struggled across the Cascade Mountains at Stampede Pass, the trains using tight switchbacks to work their way up and down the mountains. It was so steep in places that two locomotives were needed to move just five loaded freight cars. On May 27, 1888, the railroad completed a 1.8-mile tunnel through the mountains, but by the end of the decade the NP was concentrating much of its activity in Seattle, while keeping Tacoma as its official western terminus. And although Tacoma won the first transcontinental link, it would be Seattle that would have the first grand railroad depot in Western Washington, courtesy of James J. Hill and his Great Northern Railway.

The Empire Builder

James J. Hill was born in Upper Canada (later part of the province of Ontario), immigrated to St. Paul, Minnesota Territory, in 1856, and went to work for a steamboat company. Blind in one eye, Hill was rejected for military service in the Civil War. During the conflict he developed some expertise in transportation and after the war went to work for the St. Paul & Pacific Railroad. He later started his own business selling the railroads coal, a more efficient fuel than the wood most were using, branched out into freight management, and soon became moderately wealthy.

Hill, with partners, bought his first railroad in 1879 -- his former employer, the now bankrupt St. Paul & Pacific. They renamed it the St. Paul, Minnesota & Manitoba Railway Company, renovated the equipment and rails, and pushed the line west into areas ripe for settlement. By the end of the 1880s, Hill's railroad reached into what is today North Dakota and Montana, and he set his sights on the Northwest, determined to get a fair share of the opportunities it promised.

Hill missed out on the massive federal and state subsidies and land grants that had enabled the Union Pacific, the Southern Pacific, and the Northern Pacific to build the first three transcontinental rail lines with mostly other people's money. But he was determined to join the party, and to do it better than it had been done before. Using private financing, Hill began his quest west in 1889, sending engineer John Stevens (1853-1943) to map a route over the Rockies and the Cascades. Stevens soon determined that Marias Pass in northwestern Montana offered a way across the Rockies without a tunnel, and the effort moved west.

In 1890 Hill renamed his company the Great Northern Railway, which better reflected his ambitions. Later that same year a survey crew found a feasible pass through the Cascades and named it for Stevens. A tunnel was planned for the future, but for the time being the Great Northern would rely on switchbacks, although ones less tortuous than the NP's at Stampede Pass. In early January 1893 Great Northern tracks laid from both directions met at Scenic, west of Stevens Pass. Initially they ran west to Skykomish, Snohomish, and Everett, and Hill had earlier purchased the Fairhaven & Southern, which gave him a route north to Bellingham Bay.

Hill had done what no one in America had done before -- built a transcontinental railroad line without government subsidies and land grants. The next question was where the Great Northern's western terminus would be. Hill flirted openly with Everett and Bellingham, but it was soon clear that this was a tactic designed to win concessions from Seattle, where he really wanted to be.

Unlike many of the rogues who built the railroads, Hill seemed to be a man of his word. Seattle had dreamt for two decades of a rail line over nearby Snoqualmie Pass, but most of its citizens were ready to greet Hill with open arms no matter what mountain pass he crossed or what direction he came from. He would not disappoint -- before he was done he would win control of the hated Northern Pacific, change the face of Seattle, excavate under its downtown streets the tallest and widest tunnel yet dug in America, and give the city a magnificent depot and expansive freight yards befitting its status as the hub of trade and commerce in the Northwest.

Surviving Disaster

Three times in 20 years -- in 1873, 1882, and 1893 -- the railroads brought the nation's economy to the brink of collapse. The inability of many of the companies to meet their obligations triggered a cascade of bank failures in 1893 that would snowball into the worst economic depression America had yet experienced. Its effects would be felt for years, and much of the blame was laid at the feet of men the press had dubbed "the robber barons." The major rail lines had taken on huge amounts of debt to grossly overbuild, laying tracks that were "not needed, through miles and miles of uninhabited wilderness merely to insure that another road would not claim the territory first" (Carlson). Among the companies that did not survive the Panic of 1893 unscathed was the Northern Pacific, which went bankrupt that fateful year, then struggled along for the rest of the decade.

Even Hill was not untouched by the disaster, but he had taken a different approach than others and was far better able to withstand the economic turmoil. He too rammed rails through "uninhabited wilderness," but he offered immigrants passage west for $10 if they agreed to homestead along the Great Northern's route. To ensure they could make a go of it, he hired agricultural experts to teach them how to work the sometimes-marginal land. He negotiated with silo owners to keep grain-storage prices down, a boon to the farmers who would use his line to ship their products. On the engineering side, Hill mapped his rail routes to avoid steep grades and to proceed in straight lines wherever possible, giving his trains the ability to haul heavier loads, and for shorter distances. He replaced iron rails with steel, which reduced track failures, costly and dangerous derailments, and the need for constant and expensive maintenance. Not having the sizable benefit of a place at the government's subsidy trough, Hill had to innovate, and he did so with ingenuity and notable success.

A Muddled, Troubled Waterfront

Seattle's original Elliott Bay shoreline did not lend itself easily to commercial development. Steep hills rose close to the water's edge, and south of Jackson Street a muddy morass of tideland intruded as far as Beacon Hill to the east and south to the mouth of the Duwamish River. The homegrown Seattle & Walla Walla Railroad had to reach the working waterfront from the south via a spindly trestle whose sharply curved path across the mud earned it the name the "Ram's Horn."

In 1887, largely due to the influence of Judge Thomas Burke (1849-1925), the Seattle City Council passed an ordinance creating Railroad Avenue (now Alaskan Way), a 120-foot-wide railroad right-of-way along the shore, much of it submerged under Elliott Bay. Two years later the 1889 Great Fire cleared the waterfront of everything that would burn. The next year, Burke convinced the city council to grant Hill's Great Northern fully half of the 120-foot Railroad Avenue right-of-way. This sounded better than it was. By 1891 a forest of pilings propped up railroad trestles, piers, wood-paved streets (including most of Railroad Avenue), and warehouses. There was as yet little evidence of an overall plan, and very little agreement on what such a plan would look like.

This was what the Great Northern faced when its first passenger train reached Seattle from the north in January of 1893. Making matters worse, an inadequate, wood-frame terminal between Railroad Avenue and Western Avenue and Marion and Columbia streets had to be shared with the despised Northern Pacific. Hill had his hands full with other matters, including blasting and drilling a tunnel through the Cascades at Stevens Pass, but a plan for Seattle was coming together in his fertile mind, one that would change the city forever.

A Need for New Ideas

Hill had long argued that the waterfront should not be further walled off from the city's commercial center by tangles of tracks and railroad structures. The Northern Pacific was beating the drum for a large new passenger depot and freight yards on Railroad Avenue, to be shared again by the NP and the Great Northern. This infuriated Hill, who was quoted as saying that he would rather put his terminus in some other city than have "anything to do with a company so wholly lost to decency and honor" (Malone, 144). This comment was made before Hill, backed by the wealth of J. P. Morgan (1837-1913), gained effective control (although not the majority of stock) of the Northern Pacific in 1896.

The Great Northern's first tunnel at Stevens Pass was completed in 1900. In 1901, Union Pacific president E. H. Harriman (1848-1909), wanting access to Puget Sound, tried to wrest control of the Northern Pacific from Hill by buying up all of the company's stock not owned by Hill and his allies. When the ensuing battle drove up the NP's stock price from less than $200 a share to $1,000 in a single day, the New York Stock Exchange almost melted down when short sellers found themselves unable to cover their bets. When it was over, Hill still controlled the two transcontinental lines that then reached Seattle, the Great Northern from the north and the Northern Pacific from the south. But Harriman had tied up enough shares that he had to be given a seat on the Northern Pacific board. Hill and Morgan then reached a truce with Harriman, and the three, joined by John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937) formed the Northern Securities Company as an umbrella trust for Hill's rail lines. In 1904 the U.S. Supreme Court, in a famous 5-4 decision, ruled that the trust violated the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890. It was ordered dissolved, but Hill retained his control over both the Great Northern and the Northern Pacific.

Now Hill's plans faced another hurdle. R. H. Thomson (1856-1949), Seattle's ingenious, principled, and hard-driving city engineer since 1892, was leery of Hill and his outsized influence. When in the late 1890s Hill first proposed building a passenger depot and freight terminals on the tidelands south of Yesler Way, Thomson argued that Seattle needed a unified development plan, one not dictated by any single person, even if that person was James J. Hill. The Empire Builder would have to compromise, and it was with R. H. Thomson that he would do it.

A Detailed Plan

In May 1902 Hill's representatives presented Seattle's city council with detailed plans for a terminal complex west of Beacon Hill on the tidelands, which would first have to be filled. He won the support of Thomson by agreeing to bore a 5,245-foot railroad tunnel under downtown Seattle to as far south as Jackson Street, removing much of the congestion and all of the passenger traffic from the waterfront. It was a radical proposal for its time, but Hill's plans to move his trains underground and build the city's main railroad facilities on land reclaimed from the sea had undeniable logic and considerable appeal.

In October 1902 The Seattle Times, under a banner headline reading "Large Area of Seattle Tide Lands To Be Reclaimed," used nearly a full page to describe the ambitious project. The paper explained that part of Beacon Hill would be sluiced down to fill the tideflats, using water drawn from Lake Washington, and James J. Hill was given his due:

"President Hill of the Great Northern wisely saw years ago that only in the southern part of the city would sufficient room be obtained for the erection of such passenger and freight depots as were required in the leading maritime and railroad city of the North Pacific coast ... and in a year at most, it is believed, there will be ample ground available for all the facilities required by both the Northern Pacific and the Great Northern" ("Large Areas of Seattle Tide Lands...).

Building the King Street Station

Although Hill now owned the majority of stock in the Northern Pacific, he still didn't run its day-to-day operations. The NP's president, Charles Mellen (1852-1927), was a Morgan man, didn't always agree with Hill's plans, and regularly took to the local press to make his views known. The NP had long advocated a joint station on Railroad Avenue and Hill's plans for the tideflats didn't change Mellen's mind. But he eventually was won over (very likely after wringing some concessions from Hill), and after the two met in Seattle in August 1902 it was announced that work on the new passenger and freight facilities on the tideflats would start in 10 days, and work on the tunnel in 20. Hill assured the public, "When we begin -- as you very well know -- we never 'let up' until everything is completed" ("Hill Begins Depot ... ").

Hill's prediction proved more than a little optimistic, but work filling the tidelands and digging the tunnel did eventually get under way, and once started rarely let up. While that was going on, a St. Paul firm, Reed & Stem, which later co-designed New York's Grand Central Station, was named project architect. Finally, on July 3, 1903, Judge Burke, who still served as Hill's local representative, announced that workers had begun clearing the site for the new passenger depot and that "From this time on work will be practically steady on the union depot. As men and teams are needed they will be sent to that place, I understand" ("Work On the New Union Depot").

Judge Burke's understanding notwithstanding, that was not what happened. Ever vigilant, Hill was watching how Seattle's downtown commercial district was developing, and he was not entirely satisfied with what he saw. In January 1904 the Great Northern and the city agreed that parts of King Street, Vermont Street, Weller Street, and Railroad Avenue would be vacated so that "the new Union passenger station might be brought one block nearer the business section" ("Dedication Is Not Secured"). Fortunately, things had gone more slowly than Judge Burke had earlier anticipated and the foundations for the new depot had not yet been laid.

With this issue resolved, the pace picked up. By the end of July The Times reported that work was underway on the final portion of the depot's foundation. Plans were made to obtain exterior granite facing and marble for the building's interior, almost all of which had to come from sources outside the state due to local companies' inability to provide the materials in the amounts and dimensions needed. In November it was announced that a Chicago firm, Johnson & Company, the builder of Spokane's passenger depot, had won the contract for Seattle's as well, at an estimated cost of $500,000. Great Northern officials, with what was becoming a rather routine excess of optimism, predicted the work would be done by July 1, 1905. They were off by almost a year.

Ready or Not

By the beginning of May 1906 James J. Hill had had enough of delay. He issued an order that, come what may, the new station must be opened for passengers on May 10, barely more than a week away. On May 3 The Seattle Times detailed some of what remained to be done:

"...the contractor regrading King Street will find it impossible to open this thoroughfare in time to receive the Hill traffic ... .

"The Jackson Street viaduct is not half completed ... . Between Third and Fourth Avenues is a wide gap yet to be filled with steel work and a permanent pavement. Until this pavement is completed the entrance to the depot from Jackson Street ... will be difficult to even make passable.

"The interior of the depot needs nearly thirty days time to finish ... . On the lower floor chaos still rules. Work on the train sheds has but fairly started" ("Hill Insists ... ").

Nonetheless, the station opened on the designated date. Rather remarkably, there appears to have been no formal ceremony for Seattle's first big-league passenger depot, probably because Hill's dictate left no time to prepare one. On May 10 The Seattle Times could only muse, way back at page 6, about what it meant for the city:

"The days, and weeks, and years that Seattle travelers have been compelled to stand under shelter sheds and wait for trains has been finally compensated by the excellent home that has been provided for the great future, as well as the effect that will be immediately apparent along the busy water front of the city when the many passenger trains will have entirely disappeared therefrom" ("The New Union Depot").

What To Call It?

It was common practice across the country for railroad companies to negotiate with other carriers for the shared use of tracks, freight facilities, and passenger depots. The shared stations came to be known, generically, as "union stations" or "union depots," and in many cities one or the other was later capitalized and adopted as a formal name. In Seattle such sharing, called "common use," was made mandatory in almost every railroad franchise the city council granted, starting with the first in 1882.

The Railroad Avenue station that the Great Northern and Northern Pacific shared until 1906 was called the "Union Depot" on contemporary maps. Until well after its completion, the new Great Northern/Northern Pacific building was also referred to in local newspapers as "the union depot" or "the union station," sometimes with initial capitals and sometimes without.

The naming proved more difficult than it should have been. Sticklers objected that "Union Depot" was inappropriate because Hill controlled both the railroads that would use it. On May 11, 1906, the day after it opened to passengers, The Seattle Times announced that unidentified "railroad officials" had chosen the name "Seattle depot" ("Name Is Seattle Depot"). This did not end the debate. Eight days later, The Times, ignoring those unnamed "railroad officials," made a new proposal:

"The necessity of some name other than that of "Union depot" for the new Hill structure ... causes The Times to suggest that the Hill depot be known as the Northern depot — thus meaning the Great Northern and Northern Pacific" (Untitled, The Seattle Times, May 19, 1906).

This didn't stick either. After debating formulations using the words Union, Seattle, and Northern, it appears that it was the local press that finally adopted for the station the name of the street at the foot of which it stood. "King Street station," with the last word not capitalized, first appeared in The Seattle Times on August 19, 1906. It was not seen in the newspaper with all three words having initial capitals until the following year. In 1911 Harriman's Union Pacific and the Milwaukee Road would open a grand common-use depot near the King Street Station that they named Union Station, with no debate.

Elegance Revealed

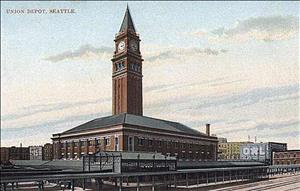

The exterior design of the King Street Station was a mash-up of styles known in the vernacular as "Railroad Italianate." City historic-preservation documents describe it more particularly as "Beaux Arts -- Neoclassical, Commercial, Italian -- Italian Renaissance" and note that "the campanile, with its prominent clock, is the building's most distinguishing feature and is based on the campanile on the Piazza San Marco in Venice" (Summary for 301 S Jackson St).

The steel-framed building was L-shaped, the long side measuring 230 feet and the short leg 135 feet. The square, 242-foot clock tower, which until the Smith Tower was completed in 1914 was the tallest structure in Seattle, sat in the notch at the intersection of the building's two legs and featured a 14-foot-wide clock dial on each of its four faces, the mechanisms built and installed by E. Howard & Company of Boston. The ground floor was reinforced concrete with granite facing on the exterior and the upper two floors were solid brick masonry faced with pressed brick. A thick terra cotta entablature ringed the building where the walls met the roof, and additional terra cotta detailing framed the windows. Other decorative elements were of both terra cotta and cast stone. All was topped by a tile-covered hipped roof, and at the building's rear long shed roofs gave shelter to those getting on and off the trains.

When passengers entered the interior of the station they were surrounded by elegance, later described by the Seattle Department of Transportation:

"When the station was opened to the public in May 1906, its grand waiting room had ornamental plaster ceilings. The plaster walls were interspersed with fluted Corinthian columns. The lower part of the walls and columns ha[d] white marble accented with glass mosaic tiles in white, green, red and gold. A massive bronze chandelier hung in the center of the main waiting room. Along with four smaller chandeliers and wall sconces, they provided illumination for the passengers inside the station. The terrazzo floor ha[d] inlaid square mosaic tiles. This created a compass shaped pattern at the station entrance and other rectangular patterns throughout the rest of the areas" (King Street Station Renovation).

Elegance Concealed

During the first half of the twentieth century, as air travel became more common and the fortunes of passenger trains went into decline, many of the classic old railroad depots around the country fell into disrepair. The King Street Station was no exception. At some indeterminate time the hands on its four large clocks stopped moving and for years were right only twice a day. The interior grew shabby, repairs went undone, maintenance was minimal. The once-grand depot began to resemble an aging bus terminal, and during the long decades of railroad consolidation and retrenchment nobody seemed to care.

It was not the passage of time alone that robbed the King Street Station of its original beauty. During the mid-twentieth century a series of ill-conceived renovations removed or concealed much of its once-elegant interior. The Seattle Department of Transportation provides a succinct description:

"A series of renovations in the 1940s, 50s and 60s ... removed the plaster and marble walls, glass mosaic tiles and covered the plaster ceiling with acoustical tiles. The historic light fixtures were replaced with fluorescent lights. The terrazzo floor was cracked and in disrepair" (King Street Station Renovation).

And worse. Windows were boarded up, wood-and-glass doors replaced with metal ones, and the huge waiting room was chopped up by wooden partitions, creating a dark warren of compartments.

Had things stayed as they were in the transportation world, the deterioration may well have gone on unchecked. But increasingly intolerable congestion on the region's highways was finally persuading a reluctant public that some form of mass transit was needed, and there was born a rail system for commuters that eventually would link a number of cities and towns that lay along the Interstate 5 corridor. The development of Sounder commuter trains and a moderate resurgence in long-distance passenger-train traffic demonstrated the continued need for a depot in downtown Seattle and would eventually spur the efforts to bring the King Street Station back to a semblance of its former glory.

Elegance Restored

That the King Street Station even survived into the twenty-first century is in large part due to its 1973 listing on the National Register of Historic Places and its later inclusion on the register as an element of the Pioneer Square/Skid Road Historical District. After a century of railroad failures, consolidations, and mergers, in 2003 the station was owned by the Burlington Northern & Santa Fe Railroad (BNSF). But the BNSF had little use for it; it was a freight-only line and leased the passenger facility to Amtrak and the Sounder commuter-rail service. The station's designation as a historic building meant that it couldn't simply be sold to a developer, and the BNSF had few other options.

Talk of restoration of the King Street Station came as early as 1991, and in 1998 the state Department of Transportation started some renovation work, helped by a $5 million contribution from Amtrak. Sound Transit would later spend more than $8 million on new platforms and means of access. By the time the station reached its centennial in May 2006, BNSF and the City of Seattle were deep in negotiations. Price was never an issue, but there were questions of liability and dozens of other legal niceties that had to be ironed out. On December 11, 2006, the city council approved a deal reached by the railroad and the office of Mayor Greg Nickels (b. 1955) for a purchase price of $1. Ownership would not be formally transferred until early 2008, at which time the city, apparently unable to cut a check for $1, tendered one for $10 instead.

The price tag for restoration and seismic strengthening originally was estimated at $29 million, but the final total nearly doubled that, at $56 million, with almost half going to seismic retrofitting. Funding came from a variety of sources. Seattle voters had approved Proposition 1 in November 2006, which included $10 million for the depot. State government contributed $10.1 million and $16.7 million came from the Federal Railroad Administration. The Federal Transit Administration added $18.9 million and King County 4Culture and the South Downtown (Sodo) Foundation contributed $210,000. A Portland, Oregon, firm, ZGF Architects, designed the renovation effort.

The Unveiling

On Wednesday, April 24, 2013, more than 500 people and a brass band celebrated the reopening of the King Street Station's passenger waiting hall. Seattle Mayor Mike McGinn (b. 1959) spoke and gave a nod to former mayor Wes Uhlman (b. 1935) for his efforts to preserve Pioneer Square's historic buildings, rather than turning the neighborhood over to developers as many had urged. Said McGinn, "It's not just about the past, but about a future where we recognize the best of the past ways of doing things" ("Local").

And the "past ways" were everywhere in evidence. The towering, ornate plaster ceiling, once marred by the bolts and cables that had suspended the 1950s acoustical-tile drop ceiling and its sallow fluorescents had been exposed, patched, and repainted. A new chandelier illuminated the now-open space, its light reflected in the repaired and highly polished terrazzo floor. Partitions that had for years divided the hall into smaller areas were gone, restoring the room's feeling of spaciousness. The baggage and ticket counters were moved from the floor's center to the margin of the room's north side. The missing marble facing on the interior walls was replaced, and windows once boarded up again let in daylight. On the exterior, a new terra cotta roof replaced unsightly asphalt shingles installed decades earlier. Unseen by the public was all the steel that was added to strengthen the structure against earthquakes, enough to build a 20-story high-rise, according to project manager Trevina Wang.

There was still a little work left to do. Although the four clocks in the central tower had been repaired in 2008 and started up in a ceremony the following year, their operation had to be suspended until some interior painting was finished. And the depot's grand central staircase that climbed from the lobby to a new entryway and a park on Jackson Street was blocked off, still in need of finishing touches.

It took James J. Hill about two years to build his King Street Station. Its restoration, since the first halting steps in 1998, had taken 15 years. But it was well worth the wait, and generations to come will be able appreciate an extraordinary example of the classic beauty and elegance that found its way into public architecture during America's Gilded Age and the early twentieth century. Ryan Hester, chairman of the Pioneer Square Preservation Board, summed up the effort and what it meant: "The outright obsession of every detail in this magnificent restoration will be appreciated by all who enjoy this space for the next 100 years" ("Local").