Teresa Woo-Murray is an artist and the great-great-granddaughter of Chun Ching Hock (1844-1927), Seattle's first Chinese immigrant, and she has done extensive research into his life and businesses. Woo-Murray was interviewed on September 18, 2015 for a project HistoryLink did in partnership with Historic South Downtown to document the historical connections between the Chinatown International District and Pioneer Square neighborhoods and the central waterfront. Dominic Black talked with Woo-Murray about Chun Ching Hock and his life.

Wa Chong and Yesler's Wharf

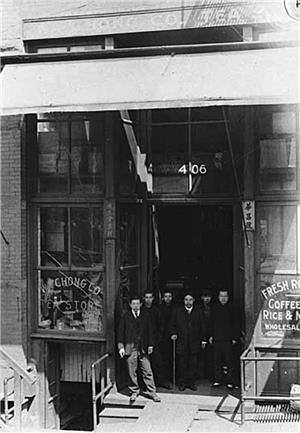

Well first of all the Yesler mill was on this wharf, right down there on the waterfront. And all the shops, all the businesses, started there. The P-I was there, just on Mill Street, Wells Fargo, and adjacent was Wa Chong. He opened a little store there and I think he opened it in a building that Yesler built.

So they're just right across the street from each other. And perhaps, and I've heard this, that before he opened the store he may have worked in the cookhouse of Yesler Mill, so he knew him either ... as an employer or just as a neighbor.

Well first of all Yesler had -- he hired Native Americans to work for him -- and I think that Chun Ching Hock might have provided that labor, he might have gone out and recruited Indians to come and work. And the reason why I think that is because of this newspaper article I read about the way that Yesler would pay his Indian laborers. He made out of some metal, maybe brass, these little coins, and they were worth a day's work -- like a dollar. And then he would, at the end of the day, he would pay his workers one of these.

One of Yesler's assistants noticed one day that the coins didn't quite look right, they weren't the right shape ... the markings on them just looked funny. So they looked into it and they found out they were counterfeit. And then the article says that there was x amount of counterfeit coins and also that Wa Chong Company and Chun Ching Hock also had been paid some of these counterfeit coins.

So I'm thinking that [for] Chun Ching Hock this was the start of being a labor contractor, by contracting to Yesler and then being paid by these coins in which he paid his -- he might have taken his cut -- and then he paid his workers.

Near the Waterfront

I believe that Chun Ching Hock's store was sort of like a place to do any kind of business, you know, a headquarters so to speak. It was on Mill Street, probably close to Commercial Street, right? I think it was west of Commercial Street, very near the water. In fact he said in an interview, he said that on the back porch of his store he could shoot wild ducks in the marsh. Yeah.

DB: Where was he interviewed?

He was interviewed by The Times, I think it's a Times interview, and he's reminiscing about the very beginning and how he advertised in the P-I every day, because the P-I office was right next door.

DB: And would he be advertising just products or would he also be --

He advertised his products. He had a little illustration of a Chinese man with a pole and things hanging, baskets hanging, which was probably tea -- I think that was the largest lettering, headline. Tea, flour, rice, all kinds of China goods. And then once in a while it would say "Live Hogs," "Tailoring," "Labor Contracting -- We Do It Quick."

He was an entrepreneur. Whatever he could see would have a profit, I think he would delve into it.

Labor Contracting

In the mid-seventies he had made enough money and he was able to build a brick building up on 3rd and Washington, and he started to expand. I'm not sure which labor contracting he had gotten into at that time, I don't see a lot of news about it, but this is when he brought in Chin Gee Hee as a junior partner. That's when I think the labor business grew, so that attracted a lot more Chinese into the city and what happened was, they all kind of congregated around this 3rd and Washington area.

He built big buildings because on the main floor he could lease them out as businesses -- you know, there needed to be laundries and restaurants and things like that. It wasn't exactly that the Chinese could just go anywhere and open a business; they were kind of concentrated in this area and then in the upper floors there were rooms to rent, for the laborers to live in. So he built a community.

And at the same time people didn't like it, they didn't like to see so many Chinese concentrated in one area. And of course they were all men, practically, because it was impractical to bring your wife or women weren't allowed to come. So it was all men and, you know, they worked hard and they liked to either drink or smoke opium, and you know … but the city was all over pretty wild, you know? It's a … it's a wild-and-woolly West town ... but for some reason people started to resent too many Chinese being here.

So he was pretty much in the center of that. He was labor contracting, bringing them in, and the city was benefiting. They built the road out to Newcastle, to Yakima, they were contracted to grade the road and for the railroad to be built, and that helped to bring some coal in. And Wa Chong was hired to cut a canal from Lake Washington to Lake Union, and this had been something other pioneers had been thinking they wanted to do, and several people tried and they failed, but they hired Wa Chong and he went out there with twenty-five guys and some horses and he cut it open.

Traveling East

He takes a trip back east and he's starting to negotiate with different merchants and talk to the shipping companies and convince them that there's business here for them if they could just come straight here.

And he goes to Butte and he opens up another Wa Chong and builds a building, and that building's still there. And a shop in Helena -- there's miners, Chinese miners there, because there's copper mining. And other places over east, going east -- I heard he went as far as Dakota and Chicago. And they get people to say that they want to trade with China, and then I think he goes to China and he starts to get interest too, in products and natural resources from the Pacific Northwest like flour and lumber which they're very interested in purchasing. So this is a benefit to the area.

I saw an article that they're complaining that they -- I forgot what it was -- some of the people in Seattle are complaining that they don't get any help from Washington, they're being ignored because they're just so far away and you know, they should have been getting federal funds -- "Well we just have to do it ourselves."

So that's, I think, kind of part of that.

Lonely Beginning

We were given, by family members, his will -- and my cousin translated it. And in it he describes what it was like to come to America and start his business. And he says that it was lonely, and it was difficult because he didn't know what he was doing, and he made mistakes and he got into debt, but he said "Fortunately, Seattle was growing." And so he worked hard and he saved his money, and he was able to get out of debt, you know, after a period of time.

DB: When he talks about it being lonely, I mean, what do you take from that ...?

I think that maybe when he first came ... it was before he got married maybe, you know. He could speak English a little bit, but he couldn't speak Chinese to other people around. There weren't very many yet. You know, when he's writing this he's 80-something ... I think he's trying to paint a picture of this journey from nothing, you know, when he's 17 and his father dies poor, to when he's going to die he's going to have all this money and after he writes this first part he's saying, "I worked my whole life so I could come to this point and it's … I can give this money to my family."