The Washougal River Bridge spans the Washougal River in Camas, in Clark County. It opened in 1908 as part of the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway (SP&S). This railroad was a joint enterprise of the Great Northern Railway (GN) and the Northern Pacific Railway (NP). It passed through Washougal and Camas and was instrumental to the growth of both towns. The development of the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway marked one battle in a long and often bitter competition between railroad men James J. Hill (1838-1916) and E. H. Harriman (1848-1909). It connected Spokane and Portland, hugging the north bank of the Columbia River along much of its route, and crossing the Columbia via two bridges at Vancouver. The Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway's corporate existence ended in 1970 when the Hill lines were consolidated to form the Burlington Northern, but the bridge served for several more decades and in 2013 was found eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. No takers could be found to remove and relocate the old span for adaptive reuse, and after more than a century of service it was scheduled to be dismantled and replaced by a new bridge in 2016.

The North Bank Road

The Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway (commonly known in its earlier days as the North Bank Road) was never an independent company, but rather the wholly owned offspring of the Great Northern and Northern Pacific transcontinental rail lines. Most of its equipment was used, handed down from the parent firms, although when the Great Northern or Northern Pacific ordered new locomotives they would occasionally add one or two to the contract for use by the SP&S. The railroad struggled for years with aging equipment and the ups and downs of the nation's economy, but its importance to the development of the areas it passed through can hardly be overstated. Trains that previously had to be barged across the Columbia River from Kalama, Washington, to Goble, Oregon, could now run straight down the north bank of the Columbia to Vancouver and reach Portland by bridge, and after its completion every town along the route could link directly to a major Pacific seaport and the transcontinental rail lines.

It was also a boon to its parent companies. Both the Great Northern and Northern Pacific had carved paths over, then through, the Cascade Mountains, but after 1908 they had an alternative to those equipment-punishing, fuel-intensive routes. Trains from Puget Sound's commercial centers at Tacoma and Seattle could meet the SP&S at Vancouver, then cross the bridges to Portland -- the region's largest port at the time -- or travel northeast to Spokane. The new route was longer but far easier, with very little change in elevation along its entire course.

The city that perhaps gained the most from the new route was Vancouver, the railroad's last stop in Washington. The state legislature passed the Port District Act in March 1911, and just more than a year later the city's voters approved the formation of the Port of Vancouver, in large part to take greater advantage of the opportunities offered by the arrival of the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway. In subsequent years the port proved to be a huge economic driver for the region and remains so today.

The opening of the Panama Canal in 1912 caused a reduction in railroad freight traffic, and the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway saw some lean times, particularly during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Its greatest years would not come until World War II, when the railroad thrived carrying war-related cargo. A greater and long-lasting benefit came with the Columbia River dams and the Bonneville Power Administration, which provided cheap electrical power that spurred development of industries up and down the river, including aluminum plants, sawmills, and chemical facilities. Most relied on the SP&S to reach Spokane, Vancouver, and Portland and, using Northern Pacific and Great Northern tracks, Seattle and other Puget Sound markets.

In 1970 the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway, after 62 years of operation, lost its personal identity when all of the lines of the sprawling Hill empire were merged to create the Burlington Northern. Its good name became more deeply buried in 1995, when the Burlington Northern merged with the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway to form the Burlington Northern & Santa Fe Railway, later called simply BNSF.

Hill vs. Harriman

By 1893 there were four American railroads that were called "transcontinental": the Union Pacific (UP), the Southern Pacific (SP), the Northern Pacific, and the Great Northern. None actually spanned the nation from coast to coast; three started in the Midwest and the Southern Pacific's eastern terminus was New Orleans. Nor did any of them have direct access to Chicago, the great pulsing heart of Midwest commerce.

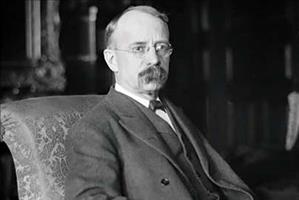

The building of the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway was just one development in a series of bitter battles between two giants of the industry -- James J. Hill, who built the Great Northern into Seattle in 1893 and bought control of the Northern Pacific in 1896, and E. H. Harriman, who bought the Union Pacific in 1897 and took over the Southern Pacific in 1901. Each man had something the other wanted. The Hill lines had only awkward access to Oregon, where Harriman's Union Pacific and Southern Pacific dominated. For its part, the Union Pacific had not been able to penetrate the rapidly growing Puget Sound country, where the Hill's Great Northern and Northern Pacific had the field to themselves.

In 1896 Hill, backed by a British noble, Lord Mount Stephen (1821-1929), and by American financier J. P. Morgan (1837-1913), won effective (but not majority) control of the perennially troubled Northern Pacific as it emerged from three years of bankruptcy reorganization. Although the GN and the NP were thereafter commonly referred to as the Hill Lines, they were run independently, with Morgan's men largely in charge of the latter. In 1901 the two companies together purchased the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railway, giving Hill the access to Chicago that both he and Harriman coveted. In a counterstroke, Harriman tried to corner all the available stock of the Northern Pacific that the Hill camp didn't own, control of which would give the Union Pacific access to Tacoma and Seattle and could cause Hill no end of trouble in the Midwest. Hill, again backed by Morgan, launched a competing effort to secure unquestioned ownership of the line.

Before the Hill/Harriman fight began, many large investors had shorted the Northern Pacific's stock in the expectation that its price would continue its long downward trend. Then, on a single Thursday, May 9, 1901, as Hill and Harriman vied to suck up every available share, the NP's stock price exploded, moving from $170 per share to, briefly, $1,000 per share. Those who had shorted it could not cover their bets. The entire stock market came close to meltdown and was rescued only through the intervention of major brokerage firms. When the dust settled, Hill and Morgan had retained control of the Northern Pacific, but Harriman owned enough stock to gain a seat on the company's board of directors.

Deciding to cooperate, for once, Hill and Harriman, along with Morgan and John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937), formed the Northern Securities Company, a trust that would hold the interests of the Great Northern, the Northern Pacific, the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy, and related smaller lines. In 1904 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the trust violated the Sherman Anti-Trust Act and ordered its dissolution, but Hill retained control of the three core railroads.

As this episode typifies, the maneuverings of the nation's competing railroads during this era were complex, opaque, and often incestuous. Separate railroads controlled by the same men would compete against each other as aggressively as they did against lines owned by others. These same men -- the industry's major players -- often served as directors of railroad companies that had conflicting interests. Enemies one day were friends the next; friends became enemies just as quickly. Their feuds were epic and prolonged, their alliances tactical, temporary, and fickle.

Moves and Countermoves

In 1900, while the battle over the Northern Pacific was starting to shape up, Harriman's Union Pacific took over complete ownership of the Oregon Railroad & Navigation Company (OR&N), which since the 1880s had tracks that crossed the Snake River at Ainsworth Junction and then ran along the south bank of the Columbia River. Part of this route had been a critical link in the Northern Pacific's transcontinental system in the years before that company made its way over the Cascade Mountains to Tacoma in 1887, and even after that the NP and GN used it to access Portland after crossing the Columbia by barge at Kalama. After Harriman took over the OR&N, he offered to let Hill continue using its tracks in exchange for access to Hill's line from Puget Sound.

Hill refused Harriman's offer, opting instead to build his own railroad linking Eastern Washington and Portland. No one had yet laid tracks on the difficult north bank of the Columbia River, and that is where Hill decided to go, using at first the assets and equipment of the Northern Pacific. One major factor in the timing of his decision was the approach from the east of another major player, the Milwaukee Road, which was completing its own transcontinental line and looking for a route to Puget Sound markets. Hill feared the newcomer might beat him to the north-bank route, and he also expected interference from Harriman. Working largely in secret, Northern Pacific representatives started buying up rights-of-way along the proposed route as early as 1903.

The secret could not be kept forever -- surveyors who denied working for Hill were using equipment clearly marked "Northern Pacific" and cashing paychecks issued by that company. Harriman caught on by 1905 and dispatched his own forces to try to block Hill's path at strategic points along the proposed route. In September 1905 a Hill representative confirmed the obvious, and by this time the Great Northern had joined in the enterprise. As Hill later explained, "I suppose the Northern Pacific would be jealous of the Great Northern building there, and we would be jealous of their building there, so we concluded that we would build jointly ... ." (Pease, 4).

A month later, at the Lewis & Clark Centennial Exhibition in Portland, Hill made a more formal announcement that the Great Northern and the Northern Pacific would, as equal partners, create a new company, the Portland & Seattle Railroad. Tracks would be laid from Vancouver to Kennewick along the north bank of the Columbia River, cross the river to Pasco on an existing Northern Pacific bridge, then follow the Snake River and skirt the edges of the Coulees and the Palouse before arriving at Spokane. Hill pointed out that only the Columbia River route offered a way from Eastern Washington west to the Pacific without the necessity of crossing a mountain pass. "Nature made the pass," said Hill, with characteristic pithiness. "Water follows the line of least resistance, and so does commerce" (Pease, 5).

The Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway

Work on the roadbed began immediately, with crews laying tracks from Vancouver east and from Kennewick west. Harriman did all he could to interfere, including snapping up some land along Hill's proposed route. The conflict reached a rather absurd low point at Cape Horn on the banks of the Columbia, where Hill had a huge crew with heavy machinery digging a tunnel from the east end, while Harriman had "six workers with pickaxes and wheelbarrows" pretending to dig one from the west (Schafer). Hill obtained a court ruling that his rival had no real intention of building on the north bank; Harriman was ordered to get out of the way, the work went on with no further interruptions, and the railroad was completed between Vancouver and Kennewick on February 22, 1908. A gold-spike ceremony was held the next month at Sheridan's Point, three miles west of Stevenson. Passenger service between Vancouver and Pasco/Kennewick began, with trains traveling from Pasco to Spokane temporarily using the Northern Pacific's existing tracks.

It has been speculated that Hill initially left the word "Spokane" out of the railroad's first name to hide his intentions from his rival. As the railroad neared completion, Spokane residents protested, and Hill accommodated them by renaming the new line the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway, giving their city pride of first place. In fact, Hill could have left the "Seattle" out entirely; the railway would never run tracks to there, but connected to its parent companies' main lines that did.

Bridging, Blasting, and Boring

The route along the north bank of the Columbia River was not an easy one to build. In many places high bluffs shouldered right up to the river's bank, and the many gullies, ravines, and streams along the way all needed to be crossed. The Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway would eventually need nearly 30 bridges and trestles along its route, as well as several overpasses and 13 tunnels. The major bridges, true engineering feats, were the two that led from Vancouver to Portland and the one farther south that crossed the Willamette River. But every bridge was a vital link on the route, and the failure of even the least of them could bring operations to a halt.

The long service of the bridges along the railroad's route are a testament to Hill's insistence that everything on the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway route be engineered and built to the highest standards. Early estimates that the entire cost of the route would be about $8 million proved shockingly optimistic. The final cost was rumored to have reached nearly $45 million, and there were even reports that Hill regretted having started the project at all. But he stuck it out, part of a long-term plan to control tracks leading all the way from Seattle and Spokane to California. This would eventually come to pass, but not until many years after his death.

Camas and Washougal

Two of the towns that the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway passed through on its route from Spokane to Portland were Camas and Washougal on the north bank of the Columbia River in Clark County, about 13 miles east of Vancouver. Their early histories are closely entangled, and even today the eastern portions of Camas cross the Washougal River and blend seamlessly into the western reaches of Washougal.

The first Euro-American arrival to the Camas/Washougal area predates the settlement of Seattle by more than a decade. Richard Ough (sometimes spelled "Howe"), a British seaman, arrived in approximately 1841, although some accounts claim as early as 1838. Additional settlers drifted in over the following decades, but nothing that merited the name "town" really developed until 1883. That year a Portland newspaper owner, Henry L. Pittock (1835-1919), decided to build a paper mill in what was at the time a small settlement called La Camas. He founded the La Camas Colony Company, which in addition to a paper mill would build a company town having everything his workers needed, including homes, stores, churches, and schools.

The city formally incorporated as simply "Camas" in 1906, a move taken in anticipation of the railroad's arrival. Between 1910 and 1920 the town's population increased somewhat modestly, from 1,123 to 1,843. By the 1930 census that number had well more than doubled, to 4,239, and by 2010 had grown to 19,355. Over the decades, the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway both spurred and sustained much of this growth.

Ough is also credited in most accounts as the first non-Native settler in what is now the neighboring city of Washougal, to the east of Camas. That town was first mapped and platted by Clark County's official surveyor, Alexander McAndrew (1834-1903) in April 1880. On May 6, 1880, the plat was recorded and the town of Washougal officially came into being. In 1908, encouraged as were their Camas neighbors by the coming of the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway, Washougal citizens decided to formally incorporate their town. In later years, a huge Pendleton Woolen Mills factory was built that as of 2015 occupied a 70-acre site in the city. In 1910 Washougal's population was a mere 456; by 2010 it was 14,095. As with Camas, the coming of the SP&S was a significant factor in its development.

In 1935 the citizens of the two cities united to create the Port of Camas-Washougal, and it is still jointly operated by the municipalities. Among the major projects developed over the years by the port are the 430-acre Industrial Park, which houses nearly 50 businesses; Grove Field Airport; a marina with moorage for more than 350 boats; and Capt. William Clark Park at Cottonwood Beach, east of Washougal. They share something else as well -- a debt of gratitude to James J. Hill and the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway.

The Washougal River Bridge

The Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway had a single-track main line until it reached the bridge across the Columbia River at Vancouver, where it split into two tracks as it entered Oregon. Approximately 15 miles to the east of Vancouver the Washougal River enters the Columbia from the north. A little less than a half-mile upstream lies an island that splits the Washougal River into two branches, and it was here that the SP&S decided to build its bridge. This island is nameless on modern maps, but on a few older ones is designated Bridge Island.

The railroad began laying track east from Vancouver on September 27, 1907, and reached the western bank of the Washougal River at Camas three weeks later, on October 18. The Washougal River Bridge was completed on November 1 and five days later the rails had reached the town of Washougal. On January 12, 1908, at Sheridan's Point, tracks coming from the west met those coming from the east, completing the portion of the route between Vancouver and Pasco. It was here almost exactly two months later, on March 11, 1908, that the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway held its Golden Spike ceremony.

The Washougal River Bridge (the official designation is "BNSF Bridge 24.8") lies entirely within the city limits of Camas, which span the river and blend into the western portion of Washougal. The railroad initially used two bridges of different design to cross the two branches of the river. The western span, which reached to the southern tip of the mid-stream island, was of a design called the Pratt truss. The original span off the island to the east was a simpler, plate girder bridge with no superstructure. This would be replaced by a second Pratt truss about five years after the line was opened in 1908.

The Pratt truss bridge design was first patented in 1844 by Thomas Pratt (1812-1875) and his father, Caleb, of Boston, Massachusetts, and soon became, with several variations, the prevalent design for railroad bridges under 250 feet in length. Originally built with a combination of wood and iron, the design was able to transition to full-steel construction without major alterations. The common feature of all steel-truss bridges is a reinforcing framework that is pinned, riveted, welded, or bolted into a series of triangular sections. These serve to distribute the primary forces to which a bridge is subjected: tension, the tendency to pull apart; compression, the tendency to push together; and torsion, the tendency to twist.

The Washougal River Bridge's two main sections are 200-foot-long through-truss spans, on which trains travels within the truss frameworks, which rise to 22 feet 6 inches on both sides and are cross-braced overhead along their 18-foot 6-inch widths. The structure of the bridge is made up of a combination of built-up steel beams and straps that are attached to one another with steel pins, a method later abandoned in favor of riveted plates. The vertical members of a Pratt truss are in compression and the inward-slanting diagonal members are in tension. The top longitudinal members of the superstructure (called the "top chord") and the beams carrying the railbed (called the "bottom chord") are straight, level, and parallel. In addition to the two Pratt truss sections, the Washougal River Bridge has two 50-foot, deck-type plate girder spans, one on the western approach leading to the first truss span and the other on the eastern side of the second truss span. These consist of two longitudinal steel I-beam girders resting on concrete piers with the railroad ties and rails sitting on top.

The long useful life of Washougal River Bridge testifies to the strength and durability of the Pratt truss design and to James J. Hill's insistence on the highest quality of materials and workmanship. For well over a century, they have borne without mishap both the "dead load" of their own weight and the weight and forces of the "live load" transmitted by the heavily laden trains that crossed them, often multiple times a day. The spans have been upgraded over the years, but have been remarkably trouble-free, although a flood on the Washougal River in March 1908 damaged portions of the new bridge, delaying the inaugural passenger run by a couple of days.

But time eventually catches up with everything, and in the second decade of the twenty-first century, it finally caught up with the Washougal River Bridge. In May 2015, BNSF announced that it would spend $10 million to replace the historic structures, part of a $235-million capital-improvement plan for its Washington rail lines.

In 2013 the Washougal River Bridge was deemed eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, both as an example of early Pratt truss pinned construction and for its central role in the growth and development of Camas and Washougal. In April 2015 BNSF issued a public notice that it would donate the two steel spans for adaptive reuse to anyone who would assume the responsibility and expense of relocating them. Unfortunately, there were no takers, a not-surprising outcome given the expense of disassembling and moving the two sections, each of which weighs more than 200 tons. Current plans call for the structures to be demolished on-site in August 2016, after the seasonal fish runs on the Washougal River.

The Washougal River Bridge was just one of many original spans along the route of the "Northwest's Own Railway." A few still survive. With the disappearance of each, one more physical link connecting the present with the past is lost. All we can do is preserve with words and pictures the story of the historic Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway, which gave the towns and communities along its route access to the Northwest's Pacific Ocean ports, and through them to the whole world.