On November 1, 1907, the Portland & Seattle Railway completes a single-track bridge across the Washougal River in Clark County. The railroad, a joint venture of the Great Northern Railway (GN) and the Northern Pacific Railroad (NP), will link Spokane and Portland with tracks that follow the north bank of the Columbia River from Kennewick to Vancouver before crossing the Columbia River by bridge to Oregon. Before the first trains run in 1908 the company's name will be changed to the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway (SP&S). The coming of the rail link will spur the citizens of Camas and Washougal to formally incorporate, and the railway will play a significant role in the development of the two neighboring towns. After more than a century, the Washougal River Bridge will reach the end of its useful life, to be dismantled in 2016 and replaced by a new span.

A Better Way West

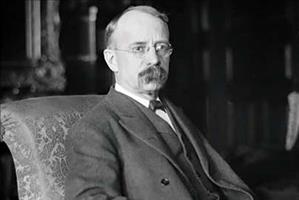

On October 3, 1905, at the Lewis & Clark Exposition in Portland, railroad baron James J. Hill (1838-1916) confirmed what had become an open secret -- two transcontinental railroad companies he controlled, the Great Northern and the Northern Pacific, planned to jointly build a railroad that would connect Spokane with Vancouver in Clark County. When completed, the route would provide the first direct rail link between Eastern and Southwest Washington, would connect at Vancouver with Great Northern and Northern Pacific tracks that ran north to Tacoma and Seattle, and would cross the Columbia River to Portland by bridge. Between Kennewick and Vancouver the line would hug the north bank of the river and, although longer, the new route would enable Hill's two transcontinentals to make fewer of the punishing, fuel-gobbling climbs over the Cascade Mountains, a particular benefit when hauling heavy loads.

Building the new railroad was difficult, particularly along the Columbia, where rocky cliffs shouldered right up to the river's north bank. Thirteen tunnels and nearly 30 bridges and trestles would be required along the 220-mile route between Pasco and Portland. These challenges were outweighed by the fact that the channel cut by the great river at Columbia Gorge was the only place in Washington that offered a way through the Cascades without significant changes in elevation. The total vertical climb between Vancouver and Kennewick was only 307 feet, or far less than two feet per mile of track. Commenting on the relative ease of the passage, Hill told the press, "Nature made the pass. Water follows the line of least resistance, and so does commerce" (Pease, 5). The Seattle Times also praised the route, calling it "to all intents as level as a table and as straight as a string" ("North Bank Line Is Formally Opened").

The new railroad also freed Hill from having to ferry trains across the Columbia by barge and onto tracks on the river's south bank that belonged to the Oregon Railroad & Navigation Company (OR&N). That line was owned by Hill's greatest rival, E. H. Harriman (1848-1909), who also controlled the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific transcontinental railroads. Harriman wanted to trade Hill use of the OR&N tracks in return for access by the Union Pacific to the Great Northern and Northern Pacific tracks that ran north to cities on Puget Sound. Hill had no interest in this; his response was to build an entirely new railroad, and to build it to the highest standards.

Early estimates placed the cost of the new line at $8 million. It ended up costing nearly six times that amount, more than $45 million. Hill was said to have expressed regret for ever starting the project, but he stuck it out. When completed, the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway and its short branch lines would pass through nearly 80 communities and small towns. These included Camas and Washougal, two small towns that lie side by side on the Columbia River about a dozen miles east of Vancouver and the fifth and sixth Washington stops on the route of eastbound trains.

In 1970 the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway, after 62 years of operation, lost its name when all lines of the sprawling Hill empire were merged to create the Burlington Northern, In 1995 this company merged with the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway to form the Burlington Northern & Santa Fe Railway, later officially renamed simply BNSF.

Camas and Washougal

Camas and Washougal were first settled in the late 1830s or early 1840s. A former seaman from Britain, Richard Ough (1790-1884), is credited as the first non-Native resident of both. The economy of Camas, the town limits of which today occupy both banks of the Washougal River where it meets the Columbia, was largely sustained by a paper mill built in the 1880s by an Oregon newspaperman, Henry L. Pittock (1835-1919). Pittock called his company town "La Camas," but the name was shortened to simply Camas when voters, in anticipation of Hill's railroad, formally incorporated their municipality on June 2, 1906. In the 1910 census, the first year it was counted, Camas's population was 1,125. One hundred years later, in 2010, it was 19,355.

Washougal, whose western limits blend seamlessly with the eastern portion of Camas, had very little in the way of industry before the coming of the railroad. In 1908, encouraged by the arrival of the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway, the town was formally incorporated. At that time there was a creamery, a condensed-milk factory, four general stores, and a variety of small farms and businesses. In 1910, two years after the railroad arrived and when the town's population was only 456, a Portland physician, J. F. Bailey, opened the Union Woolen Mills. The company went bankrupt just two years later, but the Pendleton Woolen Mills, owned and operated by brothers Clarence, Roy, and Chauncey Bishop, stepped in and took it over. The mill soon became Washougal's dominant industry and in 2015 was still one of the city's top two employers (the other being the Washougal School District). The population of Washougal in the 2010 census was 14,095.

Camas and Washougal have long enjoyed a symbiotic relationship, best illustrated when the voters of the two cities approved the formation of the joint Port of Camas-Washougal in 1935. Major projects developed over the years by the port include the 430-acre Industrial Park; Grove Field Airport; a marina with moorage for more than 350 boats; and Capt. William Clark Park at Cottonwood Beach east of Washougal.

The Washougal River Bridge (BNSF Bridge 24.8)

Camas and Washougal share something else as well -- the growth and economic development of both cities is in no small part attributable to James J. Hill and the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway. The railroad began laying track east from Vancouver on September 27, 1907, and by October 18 had reached the west bank of the Washougal River at Camas, about a half mile upstream from where it empties into the Columbia. The railroad initially used bridges of different designs to cross the two branches of the river that are created there by what on older maps is identified as "Bridge Island." The western span, which reached to the southern tip of the island from the west, was a Pratt truss design. The original span off the island to the east was a simpler, plate girder bridge. This would be replaced by a second Pratt truss about five years after the line was opened in 1908.

The bridge was completed on November 1, 1907, and five days later the rails reached the town of Washougal. On January 12, 1908, tracks laid from the west met those laid from the east at Sheridan's Point, and it was here almost exactly two months later, on March 11, 1908, that the SP&S held its Golden Spike ceremony. A celebratory train left Vancouver that morning, stopping at both Camas and Washougal on its way east. Regular passenger traffic was supposed to begin on March 16, but a flood damaged part of the Washougal River Bridge, delaying the inaugural run by a couple of days.

The Specs of the Span

The Washougal River Bridge (BNSF Bridge 24.8) lies entirely within the city limits of Camas. The span's Pratt truss design was patented in 1844 by Thomas Pratt (1812-1875) and his father, Caleb, of Boston, Massachusetts, and soon became, with several variations, the prevalent plan for railroad bridges of less than 250 feet in length. Originally built with a combination of wood and iron, the design was able to transition to full-steel construction without major alterations.

The common feature of all steel-truss bridges is a reinforcing framework that is pinned, riveted, welded, or bolted to form a series of triangular sections that distribute the primary forces to which a bridge is subjected: tension, the tendency to pull apart; compression, the tendency to push together; and torsion, the tendency to twist. The vertical members of a Pratt truss are in compression and the inward-slanting diagonal members are in tension.

On the mainland at either end the Washougal River Bridge has two 50-foot, deck-type plate girder spans, one on the western approach leading to the first truss span and the other on the eastern approach of the second truss span. These are simply two longitudinal steel I-beam girders resting on concrete piers, topped by ties and rails that span the girders.

The bridge's two main sections are 200-foot-long through-truss spans. On a through-truss bridge, trains travel between and under the truss frameworks, which rise to 22 feet, 6 inches on both sides and are cross-braced overhead along their 14-foot, 6-inch width. The structure of the Washougal River Bridge is a combination of built-up steel beams and straps that are attached to one another with steel pins, a method later abandoned in favor of riveted plates. The top longitudinal members of the superstructure (called the "top chord") and the beams carrying the railbed (called the "bottom chord") are straight, level, and parallel.

More Than a Century of Service

The opening of the Panama Canal in 1912 caused a reduction in railroad freight traffic, and the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway saw some lean times, particularly during the Great Depression of the 1930s. It did not really come into its own until World War II, when war-related cargo gave the line a major boost. The development of the Columbia River dams and the Bonneville Power Administration brought cheap electrical power that spurred the development of industries up and down the river, including aluminum plants, sawmills, and chemical facilities. Most relied on the Spokane, Portland & Seattle Railway to reach Spokane, Vancouver, and Portland and -- by using Northern Pacific and Great Northern tracks -- they could reach Seattle and other Puget Sound markets as well.

James J. Hill was known to require the highest quality of materials and workmanship, and the Washougal River Bridge's durability is testimony to that insistence. For well more than a century it carried, with little more than routine maintenance, heavily laden trains traveling between Eastern and Western Washington. But everything built by man deteriorates with time, and the bridge is no exception. By the first decade of the twenty-first century, it was clear that the span was nearing the end of its safe, useful, and very long life.

In 2013 the Washougal River Bridge was deemed eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, both as an example of early Pratt truss pinned construction and in recognition of its central importance to the growth and development of Camas and Washougal. In April 2015 BNSF offered to donate the two steel-truss sections for adaptive reuse to anyone who would assume the responsibility and expense of relocating them. Unfortunately, there were no takers, and the historic bridge was scheduled to be dismantled, scrapped, and replaced in August 2016.