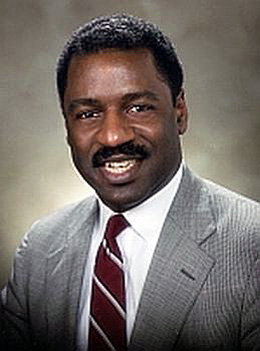

Jesse Wineberry served five terms in the Washington State House of Representatives from 1985 to 1995. He was first elected at age 29 while still attending law school. He later became the state's first African American to be selected as House majority whip. A Democrat serving districts that included central and south Seattle, he was a self-described "advocate for the under-represented," working to provide jobs, job training, workplace childcare, and small-business loans for minorities, and pushing for reduction of youth violence. He was instrumental in the creation of Martin Luther King Jr. Day as a state holiday and was a regularly featured speaker at Seattle observances honoring the late civil rights leader. Wineberry's greatest political victory came in the 1992 Democratic primary when he unseated John L. O'Brien (1911-2007), the nation's longest-serving state legislator. Wineberry's political career ended with unsuccessful bids for the U.S. Senate and Seattle City Council. In a major career shift, he founded and ran a Washington, D.C.-based company streaming live events on the Internet.

"A Real People Person"

Jesse Calvin Wineberry was born on February 16, 1955, in Sedro Wooley and adopted at birth by a religious, blue-collar couple living in Seattle's Central Area. Peter Wineberry was a shipyard custodian, Mary Wineberry was a seamstress. Together they helped found Goodwill Missionary Baptist Church. Voluntarily taking part in a desegregation effort by the Seattle school district, Jesse was bused from his predominantly black neighborhood to schools in predominantly white Queen Anne. He developed an early sense of social justice. The morning after Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968) was assassinated, 13-year-old Wineberry noticed on his way north to McClure Junior High that the flag at Garfield High School was flying at half-staff, in honor of King. Wineberry told a classmate, who convinced him they should ask McClure's principal to lower their school's flag. The principal said that would violate district policy. Wineberry was among a group of students who lowered the flag anyway. He and his classmate were promptly expelled and sent home. Mary Wineberry, who was active in the civil rights movement, immediately drove her son back to school and forcefully defended his action. He was promptly reinstated and the next day the flag was at half-staff not only at McClure, but at schools throughout the district.

At Queen Anne High School Wineberry was captain of the track team and, as a senior, quarterback of the football team that in 1972 went undefeated until losing by one point in the Metro League championship game. His coach, Reese Lindquist, said, "There was no other position Jesse was going to play but quarterback. He just has this incredible drive. I think that partly comes from a suspicion that others are trying to hold him back" ("Wineberry Takes On ...").

Wineberry earned a bachelor's degree in business administration at the University of Washington in 1977. Charles Rolland (1951-2012), a former state Democratic chairman who met him when Wineberry was a UW student, said he was "someone with a lot of drive. He seemed to be a real people person who could communicate with a lot of different types of people" ("Candidate Has Thirst ...").

After graduating Wineberry worked for nine months at a Wall Street bank and then, at age 24, became the youngest budget controller for ABC Television, overseeing financial and administrative details for programs such as "Good Morning America" and "World News Tonight." He also worked for Tacoma television station KSTW as a news reporter and as a White House and Capitol Hill correspondent. He entered law school at the University of Washington, but found his day job made it difficult to take classes there. He transferred to the University of Puget Sound's law school in Tacoma where he took night classes and, in 1980, co-founded the Black Law Students Association and was unanimously named the group's first president.

Wineberry's introduction to politics came in 1982 when he was awarded a Congressional Black Caucus Association fellowship on the U.S. House of Representatives Subcommittee on Telecommunications, Consumer Protection, and Finance. His job there included providing information for the U.S. v. AT&T case that ended AT&T's monopoly on long-distance and wireless communication.

Running for Office

Wineberry was still in law school when he decided to run for the state House of Representatives. The seat at stake was in the traditionally Democratic and highly diverse 43rd district, with neighborhoods ranging from wealthy Broadmoor to his own relatively poor Central Area. Also encompassing the University District, Capitol Hill, Pioneer Square, and the International District, the 43rd was home for much of the city's minority population. Young, energetic, and articulate, Wineberry embraced the Rainbow Coalition politics of Rev. Jesse Jackson (b. 1941). Wineberry campaigned on promises to help the poor and disenfranchised and to work to designate a state holiday in honor of Martin Luther King Jr.

In the 1984 Democratic primary Wineberry narrowly beat former district chairwoman and legislative staff research analyst Theresa Doherty (5,752 votes to 5,268), with each of them more than doubling the vote total for of Bill Burns (1927-1986), the ailing four-term incumbent. In the general election, Wineberry swamped Republican candidate Jules James 25,746 to 6,991.

Wineberry said there were 14,000 people living in poverty in the district, and he planned to work to help them in Olympia. "I'll feel very comfortable going down there and being outspoken for the poor and the elderly and the handicapped and the unemployed. ... That's what I was elected on. That gives me a clear signal" ("43rd District Winner Goes to Bat ..."). In an interview 16 months later he said, "I view my mission as spearheading economic revitalization" ("Wineberry's Crusades Began ...").

Honoring Dr. King

One of Wineberry's priorities as a freshman legislator was to create a state holiday honoring King. It was a cause long championed by George Fleming (b. 1937), who served as both a representative and senator from Seattle, but Republicans continued to oppose it as being too costly -- it would mean another paid holiday for state workers.

By 1985, the legislature had approved a school holiday honoring King, and President Reagan had signed a bill creating a national holiday to take effect in 1986. That there was no corresponding state holiday was an important distinction to labor unions, who wanted another paid day off for their members, so unions were among Wineberry's earliest allies. He introduced a bill to make the third Monday in January a state holiday celebrating the anniversary of King's birth. To appease Republican concerns about an additional paid holiday, the bill followed the federal government's lead by combining the existing February holidays for Presidents Washington and Lincoln into a single Presidents Day. Twenty-two other representatives were co-sponsors. Wineberry took extra steps to ensure the bill's passage. He asked for and received a letter signed by Reagan urging states to create their own King holidays. He also got from Fleming a list of state Republican legislators who annually opposed the idea. Wineberry lobbied them one by one, using the letter from Reagan as an additional selling point.

The state holiday became law, and newcomer Wineberry was named co-chairman for the inaugural King state and national holiday celebration in the capitol building's rotunda in 1986. A few days before that observance, he gave a rousing speech about King's dream of racial equality before a capacity crowd of about 800 at Seattle's venerable Mount Zion Baptist Church, drawing repeated applause. He stressed the need for economic development in the Central Area and Rainier Valley: "It does very little good to name a street for Martin Luther King if most of the people who live on that street live in poverty'' ("Crowd Offered 'Happy King Day'").

Wineberry was a major figure at subsequent MLK holiday events, both as a march leader and a speaker. He also sought to widen the holiday's observance. In 1990 he was chief sponsor of a resolution urging corporations to give their workers the day off.

Adding Degrees, Unseating a Legend

Wineberry earned his law degree from the University of Puget Sound School of Law in 1986. (In the 1990s, the UPS law school was acquired by Seattle University and moved from Tacoma to Seattle.) Wineberry added a master's degree from Harvard's John F. Kennedy School of Government in 1989.

Redistricting moved Wineberry out of the 43rd prior to the 1992 Democratic primary election. Instead of staying where he had been unopposed in 1990, he would be running in the 37th district, where he faced fellow Democratic incumbent John L. O'Brien, the longest-serving legislator in state history and the longest-serving active state legislator in the country. O'Brien, 80, had been in the House since 1939, except for two years in the late 1940s. A former Speaker of the House, he was considered a living legend.

But redistricting had changed the 37th to the potential advantage of Wineberry, who was popular in the district's added poor and minority neighborhoods. Redistricting also cost O'Brien an estimated 4,000 supporters from removed neighborhoods ("State Legislature"). And O'Brien was vulnerable because of his age. Wineberry played up his relative youth and fitness by bicycling around the district. The election-day outcome was described as stunning. Wineberry won 54 percent of the votes to 32 percent for O'Brien.

Also in 1992, Wineberry married Brenda Dade, a staffer at a law firm in the same Washington, D.C., building where he had worked as a summer clerk for another law firm. They had two children, Jesse Jr. (b. 1992) and Mia (b. 1993). The couple divorced in 1996.

Pushing for "Silver Rights"

Speaking at a 1993 Martin Luther King Day event, Wineberry said that what African Americans need as much as civil rights are "silver rights," his term for equal economic opportunity ("King Day Events ..."). That was a persistent theme throughout his 10 years in the House of Representatives. Wineberry's focus on economic opportunities surprised some. "When I got here," he said about his first term in the House, "leadership wanted to stick me on social-service issues, where I could help 'my people.' It's assumed that if you're black, you're from Seattle and you're a Democrat, that's what you're about" ("Wineberry Takes On ...").

When the Central Area's Liberty Bank, the state's only black-owned bank, collapsed in 1988, Wineberry was a leader in finding investors to fund its black-controlled replacement, Emerald City Bank. He also served on Emerald City's board of directors. Emerald City struggled and was closed by regulators five years after opening. But Key Bank bought it and retained the staff. Although efforts to keep it under black control had failed, Wineberry later branded the effort a success in that a bank continued to operate in the neighborhood and its jobs were saved (Drosendahl interview).

Following up on one of his early campaign promises, Wineberry sponsored the 1989 Workplace Child Care Act. Later, as chairman of the House Trade and Economic Development Committee, he promoted investment in and loans for minority- and woman-owned businesses, notably the $50 million Link Deposit loan program. Another of his projects was the 1994 Youthbuild Initiative, which offered union apprenticeships for young first-time offenders who wanted to turn their lives around. He argued, "You cannot cure youth violence by taking guns out of their hands. You need to put something positive in their hands" ("Election '94").

"Three Strikes" and Hate Crimes

When the House was considering a measure to put three-time felons in prison for life, Wineberry was among a group of representatives trying to make sure it applied only to violent crimes. That bill failed to clear the House. Instead, the state's voters overwhelmingly passed a similar initiative in 1993, creating the nation's first "Three Strikes, You're Out" law. Despite his reservations, Wineberry said he voted for the initiative:

"The greatest fear people in my district have is seeing everything they've worked for get ripped off ... As for 'Three Strikes, You're Out,' a lot of African Americans tell me 'Jesse, are you crazy? Why are we even giving these guys two strikes?'" ("Wineberry Takes On ...").

As a defender of minorities, Wineberry promoted community-oriented policing and was tough on hate crimes. He sponsored a strongly worded bill outlawing such crimes in 1993. When the Senate altered the bill, weakening language regarding cross-burning and eliminating wording that would make homosexuals a protected class, Wineberry lashed back, saying the Senate "has declared open war on blacks, Jews and gays by the hate groups that are rising in this state" ("Senate Oks Weakened Hate Bill"). He also was a strong supporter of the proposed AIDS hospice facility in Madison Valley that became the Bailey-Boushay House.

One of his proudest accomplishments was getting legislation passed that expanded the jury pool of the state's court system, adding licensed drivers to those eligible. Previously only registered voters could serve on juries. With licensed drivers included, Wineberry believed juries would have income and ethnic diversity that more closely resembled the general population, leading to fairer trials.

"Agitator for Justice"

From the time he entered the House, Wineberry was criticized for being brash, impatient, and, in one case, "an abrasive black" -- harder to deal with than the other two African American legislators seated at the time ("Jesse Wineberry Keeps Making Waves"). He admitted later that as a newcomer, he was "an angry young man. I felt, and many of the people who elected me felt, I was going into a lion's den filled with enemies. I found out that wasn't true" ("Wineberry Takes On ...")

Some considered him a self-promoter, adept at calling attention to himself. Undeniably, he knew how to make a point. In 1992, when a House committee was considering a bill that would have allowed police to stop anyone wearing "gang clothing," Wineberry stalked into the room wearing a Los Angeles Raiders jacket, a Malcolm X hat turned backward, jeans, and sunglasses. "I said, 'If this bill passes, someone dressed like me will be subject to arrest ... not because of committing a crime, not because of my conduct, but because of my clothes'" (Drosendahl interview). His point dramatically made, the bill soon was dropped.

Critics among his colleagues included Senator Dwight Pelz (b. 1941), also from the 37th District, who said, "When he was in the House, it was impossible to work with him as a team representing the 37th. He had his own personal and political agenda, and he didn't see a need to cooperate" ("Candidate Has Thirst ..."). Defenders included civil-rights activist Oscar Eason, who said, "Jesse comes from a position where you sometimes have to lead with a blast, that there are things that must be said when you represent a poor constituency. What the press misses about Jesse is that he truly feels this stuff in his guts" ("Wineberry Takes On ..."). When Jesse Jackson was running for president in 1984, he described Wineberry this way: "He is willing to be an agitator for justice" ("Wineberry Gets a Boost").

Leaving the House

Wineberry was popular enough with his fellow Democratic representatives that they elected him as the state's first African American majority whip in 1990. He later became senior ranking member of the Judiciary and Juvenile Crime and Job Creation committees. But he also was getting restless. In early 1993, he declared his candidacy for the Seattle City Council, but minutes before the July deadline filed instead for a seat on the King County Council. A week later, he withdrew from that race, saying he thought he could more effectively fight against hate crimes at the state or federal level.

In 1994, he joined a crowded field of Democrats hoping to unseat first-term U.S. Sen. Slade Gorton (b. 1928). Contenders included King County Councilman Ron Sims (b. 1948), Ballard businessman Scott Hardman, and television news anchor Mike James. Calling for health-care reform and more working-class jobs, Wineberry made his points with stirring oratory, but the leap from district to statewide was difficult financially. He raised about $140,000 for his campaign, compared to Sims' $320,000 and Gorton's $3.5 million. Sims won the 10-candidate primary with 18 percent of the votes (136,672). Wineberry finished fourth with 3 percent (just under 21,000). Gorton easily won the general election.

In 1995, Wineberry ran for an open Seattle City Council seat against Tina Podlodowski, a political newcomer who had become wealthy as a Microsoft executive. He campaigned as a self-described "advocate for the under-represented" ("Candidate Has Thirst ...") and expressed concern that Seattle was becoming a two-class city, with some prospering and others being left behind. She campaigned as someone who was forward-looking and had handled city-size budgets. Podlodowski spent $250,000 on her campaign, more than three times as much as Wineberry did on his, but he managed to beat her by a slim margin in the primary -- an outcome he called astounding. The general election was a different matter. Podlodowski won the seat with 64 percent of the votes.

In Debt, Out of Politics

His failed campaigns left Wineberry in debt. He had been living on his annual legislative salary of $29,000 and a part-time teaching job at Seattle University while trying to start a frozen-foods business. He owed $45,000 from his 1995 city council campaign and was charged by the city's Ethics and Elections Commission with 18 election code violations -- failing to make timely reports of contributions and spending, including some from his aborted 1993 city council campaign.

When Wineberry expressed interest in an open city council seat in 1996, a Seattle Post-Intelligencer editorial noted that he had "been in scrapes with election watchdogs at the city, state, and federal levels," and that until he paid his campaign debts "he has no business offering himself as a candidate. ... He's not ready to be entrusted with the public's money, judging by the way he handles his own" ("Wineberry Should Opt Out"). One of his backers, UW professor Hubert Locke (1934-2018) described Wineberry as "a terribly intense fellow, active to a fault, and it may be that he engages himself so intensely and completely that he doesn't pay as much attention as he should to the details," such as filing deadlines ("Candidate Has Thirst ...").

The Ethics and Elections Commission rejected a settlement proposed by Wineberry, and referred the matter to a hearing examiner. The examiner dismissed the commission's charges, but Wineberry still owed $43,000 from his 1995 campaign. He was mentioned as a contender for several political positions that opened in the late 1990s but did not actively pursue them.

A "Silver Rights" Legacy

From politics in Seattle, Wineberry moved into a new field in Washington, D.C. In late 1999 he founded BroadcastUrban, a pioneering webcasting company. BroadcastUrban initially focused on streaming content from urban radio stations and later concentrated on streaming video of live events such as conventions and seminars. With Wineberry as Chief Operating Office, the company expanded into movie making, opening an office in Los Angeles in 2015 to work on films -- specifically "biopics" on entrepreneurs of color (Drosendahl interview). Wineberry continued to own a home in Seattle and visit the city regularly.

In 2003, on the 10th anniversary of the Urban Enterprise Center in Seattle's Central Area, Wineberry's role in helping to establish the center was remembered. He was a leader in the 1993 Martin Luther King Day march that headed from the Central Area downtown to the Chamber of Commerce, where Wineberry gave the speech calling for "silver rights" for blacks. That message sparked a meeting between march organizers and chamber executives and led to construction of the Urban Enterprise Center, which said it had placed 7,200 people in livable wage jobs, saving an estimated $60 million in social services by getting people off welfare, and obtained $8 million in loans for small minority-owned businesses ("Success Story").

Recognition for Wineberry came full circle in 2010. At the Seattle University School of Law, formerly the University of Puget Sound law school, the Black Law Students Association he had co-founded and led thirty years earlier honored him with its leadership award.