Emmett Hawley was one of the first non-Indian settlers in Lynden, the northwestern Whatcom County town located a few miles below the Canadian border, arriving there as a 10-year-old in the early autumn of 1872. His life was similar to that of many early Whatcom County pioneers, but what set him apart is how he preserved a record of that life. Hawley is best known for his book Skqee Mus, or Pioneer Days on the Nooksack. The book, completed a little more than a year before his death at the age of 84, vividly portrays some of the everyday challenges the pioneers faced and recalls a way of life that's more and more difficult to imagine today.

Coming to Lynden

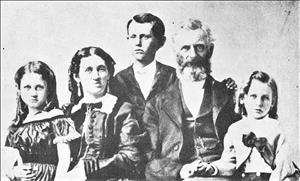

Hawley -- known all his life by his middle name, Emmett -- was born in Salem, Ohio, on May 18, 1862, to Enoch Hawley (1821-1889) and Mary Craven Hawley (1835-1892). He was the first of three children; a sister, Lida (1864-1943), and brother, Leo (1867-1890), followed. In 1863 the family moved to Iowa and stayed for nearly a decade, until Enoch Hawley suffered a sun stroke and decided to move to a milder climate. It took him a while to decide where. Somehow he obtained a copy of "a newspaper printed in Olympia, Washington Territory" (Hawley, xxiii) -- probably the Washington Standard -- and through that struck up a correspondence with Holden Judson (1826-1899), who arrived in Lynden in 1870 with his family, including his wife Phoebe (1831-1926), the first Caucasian woman in the community. Judson's descriptions of Washington Territory were so glowing that the Hawleys decided to give it a try, "although this part of the country was generally considered the jumping off place, or the end of the world" (Hawley, xxiii).

The family -- including Mary's unmarried sister, Rachel Craven, who had been living with them -- left Iowa in August 1872 and headed west on the railroad. Arriving at its end in Oakland, California, they ferried over to San Francisco and caught the steamer Ajax up to Seattle. After a short stay there, the family took the steamer J. B. Libby to Sehome (one of the four separate towns that by 1903 would become the city of Bellingham). The next day they traveled to the mouth of the Nooksack River, located at the Lummi Reservation northwest of Bellingham, and boarded a shovel-nose canoe, a small canoe with a flat bow and bottom typically used by Coast Salish people to navigate rivers. They were accompanied by Holden Judson and several Nooksack guides, including one who Hawley called "Indian Jim" (Yelkanum Seclamatan), chief of the Nooksack Tribe at Lynden (Seclamatan would later be remembered among the settlers as "Lynden Jim.")

Before long they came to the infamous log jam that stretched for three-quarters of a mile along the river near what is now the city of Ferndale. The jam had been in the river for so long that trees and shrubs grew out of it. The travelers had to unload their canoes and carry everything around it, a process that Hawley says took three hours. This wasn't as big of a problem as it might have been. The Native Americans had laid out small poles to act as a track to aid in dragging the canoes along and they carried the canoes' contents in backpacks attached by straps over their foreheads. (The log jam was cleared early in 1877, opening the river to steamer traffic.)

After spending the night in a vacant woodshed, the family arrived in Lynden the next day. In 1872, there was no real settlement yet in Lynden. The area was still predominately old-growth forest, the likes of which remain in only a few places in and near the city in 2016. (One of these is Berthusen Park, a 236-acre gem located northwest of Lynden.) The Hawleys lived briefly with Thomas Coupe and then in a cabin near the Judson farm while Enoch Hawley built the family cabin. There were so few people in the area that neighbors frequently were forced to rely on each other for help just with basic necessities, and the Hawley family was no exception. Hawley writes in Skqee Mus that they might have gone hungry that first winter had Phoebe Judson not kept them supplied with vegetables and milk. Rachel Craven helped Phoebe Judson with her daily activities in return, but even this wasn't enough -- Mary Hawley subsequently went to Seattle for about five or six months and worked to bring in extra income. In the spring of 1873 the family was able to move into their new home, and gradually they settled into their new lives.

Skqee Mus

Growing up in Lynden, young Emmett Hawley was fascinated by the Nooksack Indians and spent considerable time with them learning their language and ways. With so few non-Indian settlers in the area during these years he didn't have much choice, but that was fine with him. He explains in his book's preface that its title Skqee Mus is Nooksack for "red face," and was a nickname bestowed upon him by Indian Jim when he guided the Hawley family up the Nooksack River in 1872. Hawley maintained his friendship with the chief for decades and never lost interest in the Nooksack customs, many of which he detailed in his book. He became so fluent in the Nooksack language that he often served as an interpreter, though he modestly adds "I never could conquer the native Nooksack tongue" (Hawley, 68).

Hawley particularly admired the Nooksacks' creativity in setting traps for animals and fish. To catch fowl such as ducks and geese they would set up two cedar poles, each about 40 feet tall and spaced about 400 feet apart, to which they rigged a large net that could be raised or lowered with a pulley. They would raise the net and patiently wait until birds flew into it, then drop the net, club the birds, and either eat them for dinner or dry and smoke them for later use.

Fish was the main staple of the Nooksack diet, and tribal members utilized an efficient method of trapping them. They would build a sturdy frame of stakes across a stream that were placed so close together only a small fish could swim through them. The stakes rose more than four feet above the waterline so fish couldn't jump over them, but they didn't reach the bottom of the stream. Instead a thirty-feet-long, three-feet-wide, two-feet-deep chute extended downstream from the bottom of the stakes, with the end of the chute out of the water. The fish would swim into the chute and be carried down it by the current while two men stood inside it, grabbing the fish and throwing them out. Lynden's Fishtrap Creek got its name from one of these traps, and Hawley writes that during heavy salmon runs he would watch two men stand in its chute and throw out fish as fast as they could for hours at a time. (He says the trap was located about a quarter-mile above where Lynden's City Park is today.)

Long and Dangerous Roads

In the earliest days there were virtually no wagon roads in the Lynden area, just foot trails. Logs served as bridges across the streams and creeks. This began to change during the 1870s and early 1880s. The first roads to be built were typically corduroy roads, which were just logs laid across a roadbed. Hawley writes that cedar logs were often used. Though no fun to ride on, they beat the alternative of trying to drive a wagon down a road that was either a swamp in the rainy months or filled with potholes during the dry months. A trip from Lynden to Whatcom (another town that would become part of Bellingham) down the corduroy road in the mid-1880s could be expected to last about eight hours if all went well, though the road in that day took a different, and longer, route than present-day Guide Meridian Road.

These weren't easy trips. Aside from the difficulties of traveling on the road (it was often easier to walk than stay in a wagon), a trip to Whatcom could get you killed. Because most of the thick forest had not yet been cleared, windstorms took on a special meaning when early pioneers found themselves out in the woods. Fir trees are known for their shallow roots and are prone to fall in heavy winds, especially if they have been compromised by fire or the ground has been saturated by rain. Hawley writes of one man traveling to Whatcom in a windstorm when trees and branches began falling all around him. He was hit and suffered a broken leg and had to crawl more than a quarter-mile to the nearest house. Even if it wasn't windy, any number of things could cause wagons to flip over on the treacherous roads, throwing their occupants out and injuring them. And occasionally travelers edging across a creek on a solitary log would fall into the water and drown. There was no such thing as a casual road trip in Whatcom County in those days.

Social Clubs and Social Norms

Despite the daily challenges just to survive, the pioneers had little trouble finding ways to party. Hawley was an accomplished fiddler (something he was particularly proud of) and was in demand at housewarmings and dances. Dances were huge in those days -- they were one of the few ways people could socialize -- and participants would often stay up into the wee hours of the morning tripping the light fantastic. Fraternal orders (social organizations) developed as the town grew and also provided a welcome outlet for settlers. Lynden's better-known organizations included the Modern Woodmen, Odd Fellows, and perhaps its best-known institution, the Clam Diggers Club.

Notwithstanding the need of early pioneers to rely on each other, nineteenth-century social norms (and prejudices) were still rigidly followed. Hawley writes of first meeting his future wife, Lydia Sheffer (1869-1910), and says her mother called her away, scolded her for talking to a strange man, and whacked her across the back with a broom. Another time he was at dance in Whatcom and saw an attractive young woman. He approached one of the hosts and asked for an introduction. The host laughed and gently chided him: "Why, don't you know who that is? She's a half-breed from Lummi Island" (Hawley, 108).

Large and Consequential

Hawley had a full life in Lynden. He and his family operated two different general stores there in the 1870s and 1880s. He piloted an early steamer on the Nooksack, the Edith R, though travel to Whatcom was not necessarily faster by steamer than by corduroy road -- he notes that sometimes a round trip took three days. (The steamer landed at "Hawley's Landing" in Lynden, where today's Hannegan Road intersects the Nooksack River.) He served as the unofficial town dentist for a while, though he had no training other than a few tips from his mother. He built and operated a sawmill for several years in the late 1880s, he farmed, and he helped build some of Lynden's earliest buildings. In 1913 he developed one of the city's earliest service stations, though he rented it out instead of running it himself. He served as marshal and justice of the peace and was on the city council. He also helped organize the Timon School District and served on its board. (Timon is a now-vanished community which was located between Lynden and Everson; Hawley lived there in the 1880s and 1890s.)

Hawley was married twice, first to Lydia Sheffer in 1884. They had nine children: Warren (1885-?), Pearl (1886-?), Everett (1888-1926), Frank (1890-1960), Ernest (1892-1911), Ray (1895-1992), Lulu (1897-1991), Esther (1899-1952?), and Vernon (1904-1992). After Lydia's death in 1910 followed by his son Ernest's death four months later, Hawley fell into a deep funk and moved to Blaine to get his mind off his problems. It worked: "During this time, I got to feeling so much better, that I sort of gave up the idea of dying for awhile and decided the proper thing to do would be to get another wife," he explains with typical Hawley humor (Hawley, 173). In 1912 he married Irene Kimbrel Long (1879-1956), a widow with three sons. Together they had four children: Clarence (1913-1994), Clyde (1914-1992), Robert (1915-1988), and Ruby, born in 1923 when Hawley was 61 years old. He died in Lynden on July 24, 1946.

Pictures of Hawley show a medium-sized man with a twinkling eye and a ready grin, the kind of guy who would sit down with you and tell you stories for hours and you'd listen to every word. He finished Skqee Mus in the early months of 1945 as World War II was nearing its climactic end, and explains in his final paragraphs why writing it was important:

"Compared with the momentous events of the present day, the lives of the pioneers seem dull and monotonous, but to the actors who took part in the drama of the seventies [1870s], when their very existence depended upon a struggle for survival, seemingly casual occurrences loomed large and consequential. There were no dull days in their lives. Small favors were gratefully received and acknowledged ...

"And now I have come to my story's end. If the reader gets from these simple annals a fraction of the pleasure I have derived from compiling them, I shall feel well repaid for the labor spent; if they serve to revive fond memories in the minds of my old friends, and awaken an interest in days long past, in the thoughts of my young ones, then my efforts shall not have been in vain" (Hawley, 174-175).