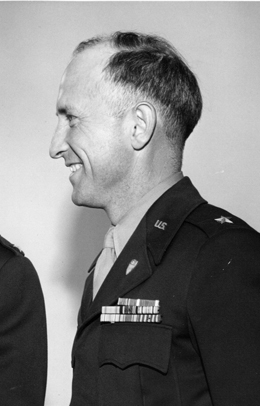

On April 18, 1942, Major Ensley Llewellyn (1905-1989) of Tacoma publishes the first edition of the World War II

Stars and Stripes

newspaper. General Dwight D. Eisenhower (1890-1969) had directed Major Llewellyn to establish a newspaper for the troops. The first edition, published in London, is an eight-page weekly with Major Llewellyn the officer in charge. It will be a success, prompting General Eisenhower to request it become a daily. The

Stars and Stripes

newspaper becomes the soldiers' paper, written by soldiers for the soldier. Its substantial profits are turned over to the army welfare fund.

From Spanaway to Tacoma

Ensley M. Llewellyn was born in Spanaway. His father, Guy K. Llewellyn (1873-1956), spent a lifetime in the advertising business. His mother, Grace G. Llewellyn (1876-1955), encouraged the children to study and advance in their careers. Ensley completed grade school at Spanaway School and then attended Tacoma’s Lincoln High School. He attended the College of Puget Sound (now University of Puget Sound), and Washington and Lee University in Virginia.

In August 1922 he joined the Washington National Guard serving in Troop B, 58th Machine Gun Squadron, which trained at the Tacoma Armory. He enlisted as a private and reached the rank of first sergeant in June 1927. First Sergeant Llewellyn attended the officer's course and was commissioned a second lieutenant on March 13, 1929.

Ensley Llewellyn followed his father's calling as an advertising person. He served as advertising manager for the John Dower Lumber Company, one of the largest retail lumber companies in the United States.

In October 1927 he married Ruth Chittenden (1907-1984). They had two sons. In 1928 he established the Llewellyn Advertising Agency and Ruth Llewellyn served as the company bookkeeper.

Stars and Stripes

On February 3, 1941, Major Llewellyn was activated into the regular army. He was one of the three first officers to reach England in 1942. He served on General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s European Theater of Operations staff. Major Llewellyn's duties included press censorship and plans to counter German Nazi propaganda.

In March 1942 General Eisenhower asked Major Llewellyn to establish a newspaper for the overseas armed forces. Llewellyn obtained $1,300 from army funds and added $876 of his own money to start Stars and Stripes for the third time. It had been a newspaper for military service members during the Civil War and again during World War I.

The first edition was published on April 18, 1942. It was only eight pages due to the shortage of newsprint. It was published in London but it emphasized news from home, especially sports.

It was so successful that General Eisenhower asked that it become a daily. On November 2, 1942, the first daily issue was published. The paper was profitable, earning about three million dollars in its first two years and providing the profits to the army welfare fund.

By the end of the war Stars and Stripes was published in 16 separate issues in different theaters of operations with a daily circulation of two million. Its readership was much higher since free copies distributed to frontline troops were typically shared with five or six others.

On October 1, 1943, Llewellyn was promoted to lieutenant colonel. He continued to oversee the continued growth of Stars and Stripes and also published "Army Talks," pamphlets that informed soldiers on current issues. He also directed the preparation of radio informational broadcasts.

D-Day

On June 6, 1944, in the invasion known as D-Day, more than 160.000 Allied troops landed on the coast of France to begin to fight Nazi Germany on the beaches of Normandy. When Llewellyn learned of the invasion, he rushed to a British staging area to get transportation to France. He wanted to get on the third or fourth landing wave, but he had to wait for the 12th landing. Once ashore he and several staff headed for Carentan, France, which the 101st Airborne Division had liberated.

Llewellyn's first action was to take over the local printshop. He then located a Carentan signmaker and had him create a banner reading "Stars and Stripes Continental Edition." A French edition of the paper would be soon produced. As with all the editions, it was produced by enlisted men, many of whom had been in the newspaper business before joining the army. Andy Rooney (1919-2011) has said that Lieutenant Colonel Llewellyn admitted that he knew little about the newspaper business and therefore did not interfere in its publication.

The Helping Programs

Llewellyn introduced two hugely successful programs at Stars and Stripes. In October 1942 he started a War Orphans support where units contributed to a Stars and Stripes fund and the Red Cross administered it at no cost to the newspaper. The program initially supported English orphans but expanded as the war progressed.

American soldiers raised money in various ways. They fined themselves for swear words, engaged in commercial endeavors, and donated their own money to support the war-orphan fund. Thousands of orphans received a $400 grant that was spread over five years. Lieutenant

Colonel Llewellyn also established a hugely popular service, the Shopping Service. Soldiers could order through the newspaper items from Parisian stores and the gifts were mailed home. More than three million bottles of perfume were shipped to wives, girlfriends, and mothers back home.

Llewellyn was less successful in bringing military discipline to the Stars and Stripes pressrooms. These attempts included inspections and sports events that the very independent newsmen turned soldiers made a mess of.

Near the end of the war Lieutenant Colonel Llewellyn returned to Fort Lewis to separate out of the regular army. He was released on July 15, 1945. He had received the Legion of Merit for exceptional service and achievement, and the Purple Heart.

After the War

Following his army release, Llewellyn resided in a University Place home overlooking Puget Sound and managed the Llewellyn Advertising Agency. In the public service area he was named head of the Washington State Traffic Safety campaign. On February 25, 1947, Governor Monrad Wallgren (1891-1961) appointed him Adjutant General, commander of the Washington National Guard holding the rank brigadier general.

The major event for the Washington National Guard during his command was in June 1948 and the huge floods which devastated the Pacific Northwest. Brigadier General Llewellyn visited the areas hard hit by the floods and directed the rescue and recovery effort.

Administrative Irregularities

On May 2, 1949 Governor Arthur B. Langlie (1900-1960) asked Llewellyn to resign his adjutant general position. Llewellyn refused, so the governor relieved him of duty. The governor asserted that he asked for the resignation because of "administrative irregularities" in the adjutant general’s office. Llewellyn responded that his relief was political. A Democrat had appointed him and Governor Langlie was a Republican.

Governor Langlie established a court of inquiry to review 12 charges of irregularities. The board sustained 11 of the 12 charges. They included improper expenditure of funds, unauthorized use of state property, exceeding the budget, and failing to respond to fire-safety hazards in a Seattle armory.

With the court of inquiry finding, Governor Langlie fired Llewellyn on July 6, 1949, and he appointed Lilburn H. Stevens (1902-1978) as the adjutant general. Llewellyn challenged his firing in court. On January 9, 1950, the Thurston County Court found him to be the adjutant general and issued an order to that effect. On January 10, 1950, with a court order allowing him access to the adjutant’s office, he appeared at the Camp Murray National Guard headquarters. Twice he tried to enter the headquarters building but guards at the door refused to allow him into the building, following the order of Brigadier General Stevens. The standoff between the two generals became known as the "battle of Camp Murray."

The issue went to the Washington Supreme Court, which ruled against Llewellyn. But in the end a compromise reached with Brigadier General Llewellyn allowed him to retire.

Continuing Service

Llewellyn continued his public service activities. He served several years as the Program Chairman YMCA Pacific Northwest Area Council. In April 1962 he was named director of the Washington Department of Civil Defense. He directed a major Civil Defense drill, Relo VII, in July 1963. The drill involved 350 men, women, and children relocating after a "nuclear attack" on Washington. Llewellyn served as Civil Defense director until July 31, 1966. He also served as a Washington state representative to the 1980 White House Conference on Aging.

Throughout his life Ensley Llewellyn was active in politics. He was involved in advertising for about 500 campaigns.

Ruth Llewellyn died in 1984 and Ensley remarried Vera Hoveland Howard (1910-2012). On July 19, 1989, Ensley Llewellyn went to his physician for a checkup and died in his doctor's office.