A few Japanese immigrants arrived in the San Juan Islands late in the nineteenth century to work in fish canneries; seasonal employment was arranged by Seattle labor contractors and not until 1917 did a worker take up residence in Friday Harbor. Japanese immigrants also worked in the islands as fishermen, in lumber camps and orchards, on farms, and in domestic service. The largest population of Japanese Americans in the islands was at Roche Harbor on San Juan Island, where John S. McMillin (1855-1936) employed Japanese workers at his lime works as "powdermen" in the quarries, in factories, as woodcutters and teamsters, and especially in domestic service and as gardeners. Workers sent for brides from Japan, and the company provided housing and employment for them as well. The number of Japanese residents dwindled after 1910. The last left Roche Harbor in 1932 and World War II internment forced the last Japanese American family then on the island to leave in 1942. Local attitudes toward the early Japanese residents varied, and some prejudice and discrimination were evident, but white islanders were largely tolerant of their Japanese American neighbors and evinced a growing interest in Japan and Japanese culture.

The first Japanese citizens to arrive in what would become the state of Washington are believed to be three sailors from a disabled, storm-driven ship that went astray from Japanese waters and drifted to the western shore of the Olympic Peninsula in 1834. In Japan the ruling Tokugawa regime had kept the country closed off from outside influences for more than 200 years, and the unfortunate sailors were never allowed to return. In 1868, however, the Meiji Restoration and rapid opening of the country to Western ideas and culture resulted in a major transformation of Japanese society and many peasants, burdened by new taxes and regulations, began arriving in U.S. ports seeking work and opportunities for a better life. Some came to the Northwest via Hawaii, but by the last quarter of the nineteenth century ads in Japanese newspapers were luring young men directly to Northwest cities like Seattle for work on the railroads and in mines, canneries, sawmills, and other growing industrial enterprises. Some first worked on and then established their own farms or built small businesses to serve the expanding Japanese community. By the end of the century Seattle had a busy, thriving "Japantown."

Packing Company Workers and Fishermen

Cannery labor shortages probably brought the first Japanese workers to the San Juan Islands, located between the Washington mainland and Vancouver Island in Northwest Washington. Sent initially by Chinese labor contractors from Seattle and later by Japanese contractors, small numbers of Japanese workers joined larger contingents of Chinese workers during the salmon runs to provide much-needed labor for the Island Packing Company (later the Friday Harbor Packing Company, leased from Pacific American Fisheries) and other packing companies. Living quarters for the two groups were kept separate as ethnic tensions were high, especially leading up to and following the Sino-Japanese War of 1894. The cannery workers were on the island for the season only and then transported off to other locations, so very few tried to take up permanent residence.

A notable exception was Jack (Kokeji) Saoka (1889-1960), an enterprising cannery worker among the later Japanese arrivals, who was eventually promoted to foreman and who later left the cannery to establish a florist business and nursery on San Juan Island. He and his family continued to live on the island until, in 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt (1882-1945), responding to fears prompted by the outbreak of war with Japan, signed Executive Order 9066, requiring that all Japanese residents be relocated away from West Coast areas to internment camps inland.

Other Japanese residents in the San Juan Islands included salmon fishermen, some working on their own boats. A brief report in the San Juan Islander of August 17, 1899, noted that among the casualties of a storm in the Strait of Georgia that had caused the loss of seven fishing boats was a Japanese fisherman who had drowned in the turbulent waters. And a few years later, a Japanese fisherman's motor sloop was reported to have been seized by the customs authorities for equipment violations. In addition to the hardships of their work, the Japanese fishermen were routinely subject to discrimination of many kinds. As just one example, cannery owners negotiated each year for the price of the salmon catch, and Fraser River and other packing company officials regularly paid Japanese fishermen less per fish than they paid white fishermen. Eventually most of the fish processed in the local canneries were caught in company-owned fish traps, rather than procured from independent fishermen, and many, of all nationalities, lost their main source of income.

Roche Harbor Lime Works

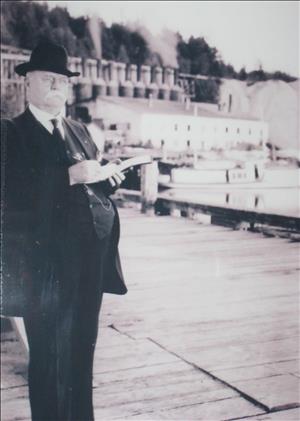

Japanese residents were also employed on the islands in lumbering, domestic service, farming, and other occupations, but by far the largest concentration of Japanese workers was at the Tacoma and Roche Harbor Lime Company (later the Roche Harbor Lime and Cement Company), incorporated by John S. McMillin (1855-1936) in 1886. There had been several small lime-quarry ventures in the islands since the 1850s. However, McMillin's vision and capital changed what had been a primitive lime operation on the northwest shore of the island into the largest lime company west of the Mississippi. The lime deposits at Roche Harbor had originally been worked by the British Army when it occupied English Camp on nearby Garrison Bay from 1860 through 1872 during the Pig War dispute, but they passed into private hands at the end of the occupation. McMillin's Roche Harbor lime works, when fully developed, included not just quarries, factories, and warehouses, but a company store, barracks housing, a doctor's office, and a post office. The stately Hotel de Haro, which first served as temporary employee housing, a dining hall, and even the McMillins' home before becoming a gracious residence for visitors, was built at waterside, and a nearby Methodist church functioned during the week as a school for the growing number of children at the site.

John McMillin was a dominating figure in the mold of his contemporary "robber barons," strong of character and a hard-headed, demanding businessman, but sociable and on generally good terms with his employees. Roche Harbor was very much a company town. Employees initially were paid in company scrip in denominations from one cent to $20 in coupon books redeemable only at the company store; it was McMillin's opinion that "workers were inclined to squander their money on liquor, gambling, and other sinful pursuits" (Crawford). Later it was possible to receive cash wages, but shopping other than at the company store was actively discouraged. The McMillins lived in a large comfortable home overlooking the harbor and entertained lavishly. The community was relatively isolated and provided its own leisure as well as work activities. The Christmas party was always a favorite and movies were shown weekly in the community hall. The Fourth of July, too, was celebrated enthusiastically and everyone participated. As part of the 1911 festivities, according to the San Juan Islander, "At the front of the hotel there was a Tug-of-war between the Japanese and Americans" (July 7, 1911, p. 8).

Japanese Workers at Roche Harbor

McMillin employed Japanese workers almost from the outset. Experienced with pyrotechnics, they worked as "powdermen" in the quarries, as well as in the factories, as wood cutters, as teamsters, and especially in domestic service and as gardeners. Working in the quarries, factories, and around blasting was hazardous and accidents were all too common. Brief reports in the San Juan Islander at the turn of the twentieth century record injuries to Japanese employees from explosions, equipment failures, and even an accidental shooting. In 1889 a Japanese worker's foot was battered by a large falling timber in an incident that occurred in the barrel factory, and the newspaper noted "his was the fourth accident at the mill within a week" (San Juan Islander, May 11, 1899, p. 3).

Immigrants arrived at Roche Harbor (and elsewhere in the San Juan Islands) both legally and illegally. Some Japanese, bypassing legal immigration requirements, contracted with smugglers (often Japanese themselves) who promised to bring them from Canada to the islands and find them employment. When caught, the smugglers were detained by immigration officials and prosecuted in federal courts. In 1900 a Japanese smuggler with 13 unlucky clients was arrested in the woods near Roche Harbor. It was so late in the evening that "the officers brought the whole party [to Roche Harbor] and put them in jail for the night and, after providing them with a good hotel breakfast, left with them for Whatcom, the nearest point at which there is an immigration inspector stationed" (San Juan Islander September 6, 1900, p. 3). And just the next year an immigrant inspector brought in 24 undocumented Japanese migrants: 22 taken from a Waldron Island camp where wood was being cut for the Roche Harbor lime works and two more seized at the company store. The smuggler was one of the Roche Harbor gardeners.

Home Life

By 1900 more than 30 Japanese workers were employed at Roche Harbor. Because the quarry and lime works provided relatively stable, long-term employment, and because McMillin had no prohibitions against married couples and indeed accommodated them, Japanese workers were able to marry and establish families. Single men would arrive first and later send to their villages for "picture brides." Marriages would be arranged for them by their parents in Japan, and soon there were children playing on the grounds and attending the on-site school. Occasionally note of the growing population even appeared in the local newspaper: "The Japanese colony is increasing. A late arrival came without any 'kippel' (passport) or landing certificate from an immigration agent. It is a baby" (San Juan Islander, September 28, 1899, p. 3).

McMillin provided housing for all his workers: barracks for the single men and small cottages for married couples. Japanese housing was segregated in an area near the barrel factory generally referred to, using the common racial slur, as "Jap Town." Often both husband and wife were employed. Many of the Japanese workers provided domestic labor around the McMillins' home and grounds as housekeepers, cooks, gardeners, and day laborers. Louella McMillin (1857-1943) taught the cooks how to make the family's favorite recipes, including the stuffing for the Thanksgiving turkey. Relations between the McMillins and their Japanese staff were reportedly very good, and some friendships lasted long after the Japanese families had left the island. A granddaughter of the McMillins recalled "receiving a crate of cantaloupes each season from families that had moved to eastern Washington to farm" (Walker).

Other Japanese employees worked in the Hotel de Haro as cooks, butlers, and waiters. Gradually, however, Japanese residents left the island and moved on to new pursuits, and by 1920 the census recorded only a few Japanese American families remaining at Roche Harbor. The last one, Hisaku Yasuda, a powderman, gardener, and midwife; his wife Ichi, a cook; and their eight children, all born at Roche Harbor, left the island in 1932.

Community Attitudes

White islanders seem to have had somewhat ambivalent views about the Japanese in their communities. Early in the twentieth century, for example, the platform of the Democrats in San Juan County asserted, "We denounce the wholesale importations of Japanese and other cheap labor ... to the detriment of the entire working and tax paying class of the county," (San Juan Islander, October 22, 1904, p. 1). A few years later an opinionated, but anonymous, commentator declared in a local paper, "The Japs should not get 'sassy' or too 'chesty.' The average American wishes to be fair, but he is an animal not to be tantalized too much" (Friday Harbor Journal, June 20, 1907, p. 4). However, others saw the issue differently: "The Japanese have as much right to be here as any nationality. If they enter the country in the proper way, then abuse or maltreatment of them in any manner cannot be justified upon any grounds," opined the San Juan Islander on December 27, 1900 (p. 2).

Meanwhile, throughout the first decades of the twentieth century, islanders were reading in the newspaper long lists of "Interesting Facts about Japan" (San Juan Islander, September 16, 1905, p. 4), and numerous articles on Japanese culture and the developing political and trade relations between Japan and the United States. The women of San Juan and Orcas islands even organized Japanese-themed receptions and parties where they dressed in pseudo-Japanese style and entertained with decorations and prizes seen as Japanese. Japanese American children from Roche Harbor, educated there through their elementary years, attended Friday Harbor High School, made friends, and did not seem to have experienced overt discrimination or harassment.

The Japanese American population declined quickly after 1910, and only two families remained on San Juan Island into the 1930s. Fewer cannery workers were needed even temporarily, as mechanization took over many of the least-skilled tasks, and local employees, including increasing numbers of women, were sufficient to supply the labor required for the more complex work.

"To Our Many Friends"

By the early 1940s, Jack and Yuki (1899-1962) Saoka and their family, who were operating a flourishing nursery and florist business in Friday Harbor, were the only Japanese residents remaining on San Juan Island. They were respected and popular islanders on December 7, 1941, when Japanese forces attacked Pearl Harbor, precipitating United States involvement in World War II. Appalled by the attack and determined to assure their neighbors of their loyalty, the Saokas, just days later, asked that the following letter be published in the Friday Harbor Journal, where it appeared on the front page of the next issue.

"To our many friends and acquaintances on San Juan Island we wish to send this message:

"We have nothing but sorrow and regret for the attack made on the United States, by the land of our birth. In our hearts we have for many years felt that the land of the free -- the United States -- is our real country. We would long ago have made application to become citizens of this country, if that had been possible. Whatever it is possible for us to do for the success of the United States, we shall be glad to do.

"You all know we have a small greenhouse. It is well stocked with a lot of beautiful flowers and plants. Now we cannot sell them, and you cannot buy them. We would (if it is possible) like the Chapter of the American Red Cross to have all the flowers, plants, and shrubs. If they will appoint a committee to make the arrangements, we will give all the flowers, and plants, all the money, every cent of it is for the Red Cross.

"In all sincerity we say:

'God Bless America.'

JACK SAOKA

MRS. J. K. SAOKA

Friday Harbor, Washington" ("To Our San Juan Island Friends ...")

Although the Red Cross would have liked to accept the Saokas' gift, the organization had no means to liquidate or otherwise utilize the materials, so the local American Legion post was asked to assume responsibility for selling all the plants and donating the proceeds back to the Red Cross. Articles appeared in the newspaper notifying islanders of the sale:

"The [January] weather ... does not turn a person's thoughts to flowers and plants, however, the Red Cross needs the money, so we of the Legion appeal to you to investigate the stock at the post office and at the greenhouse and buy what you can use this spring," ("Legion Makes Appeal ...").

Just a month later, the Saoka family, like all Japanese Americans living near the Washington coast, were required to abandon their homes and businesses and report to hastily prepared temporary quarters at an assembly station at the Puyallup Fairgrounds near Tacoma. It was just the first stop before forced internment far inland. The Saoka family never returned to live on San Juan Island, but Jack and Yuki, along with Jack's first wife Fuji Saoka (1889-1926), are buried in the cemetery in Friday Harbor, the community they had loved and had always considered their home.