On November 28, 1883, a statute passed by the Washington Territorial Legislature earlier that day is approved by the governor and Skagit County comes into existence. It is formed from the southern part of the existing Whatcom County, which was created by the territorial legislature in 1854 during its first session after Washington Territory was established in March 1853. Non-Native settlement along the Skagit River in Northwest Washington has progressed slowly, retarded first by the unrest of the Indian Wars of 1855-1856 and then by two massive logjams that prevented passage on the river and were not cleared until 1879. But by September 1883 residents of the southern portion of Whatcom County are agitating for division, and before the end of the year the territorial legislature heeds their call. Skagit County is one of seven new counties created in 1883, a number exceeded only by the eight counties formed during the legislature's inaugural session in 1854.

Along the Skagit River

For thousands of years before the first European explorers arrived, the land bordering the Skagit River was home to several Native American tribes, notably the Upper Skagits, who lived inland along the river's course, and the Swinomish and Lower Skagits, whose lands included numerous islands and the coastal areas surrounding Skagit Bay, Padilla Bay, Fidalgo Bay, and Saratoga Passage. All were Coast Salish peoples speaking the Northern dialect of Lushootseed, one of the Salishan family of languages.

With the signing of the Point Elliott Treaty on January 22, 1855, these three tribes, along with many others, surrendered most or all of their ancestral lands in return for cash, relocation to reservations, and promises that they would have continued access to traditional fishing and hunting grounds. Under the treaty, the Lower Skagits and several smaller tribes and bands were consolidated with the Swinomish Tribe, sharing its reservation on the southeastern end of Fidalgo Island. The Upper Skagits were considered too scattered to merit formal tribal status, an inequity that was not set right until 1974 when the tribe was granted full recognition.

The treaty with the Indians opened up the extraordinarily fertile land of the Skagit River delta and Skagit Valley to non-Native settlers, who were not too long in coming but whose numbers increased quite slowly. An early attempt by the newcomers to farm on the delta was stifled by the Indian Wars of 1855-1856 and not revived for several years. In 1859 the first permanent non-Native settlement in what is today Skagit County was established on a fern-covered prairie on Fidalgo Island. Among the first to set down roots there was Robert H. Davis, a nephew of Jefferson Davis (1808-1889), soon to become president of the Confederate States of America. From these beginnings would eventually arise the city of Anacortes, which slowly developed over nearly three decades before being formally incorporated in 1891.

Settlement on the mainland was taken up again near present-day La Conner in 1867 and gradually worked its way east up the course of the Skagit River. By about 1870 it had reached as far as present-day Mount Vernon, which was formally founded and named in 1877. The discovery of gold in 1878 at Ruby Creek far up the Skagit brought prospectors and more settlers. Two massive logjams that blocked the river, one below Mount Vernon and one above, were cleared by 1879, making more land accessible and allowing easier access to the west slope of the Cascade Range and its thick forests and rich mineral deposits. But as late as 1881 Mount Vernon's population was still just 75 people, and further growth would be slow.

A Legacy from Oregon

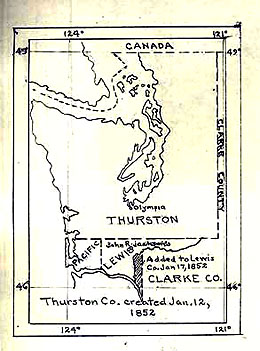

Before the creation of Washington Territory on March 2, 1853, what is now the state of Washington was part of Oregon Territory, which had been established in 1848 and covered a vast region ranging from the California border to the 49th parallel and from the Pacific Ocean to the Continental Divide. In the five years between 1848 and 1853 the Oregon Territorial Legislature created a total of eight counties north of the Columbia River that would be inherited, intact, by the new Washington Territory: Clark, Lewis, Jefferson, King, Pacific, Pierce, Thurston, and Island.

In January 1853, less than two months before Washington Territory came into existence, Island County became the last to be created north of the river by the Oregon Territorial Legislature. It encompassed what are today Snohomish, Skagit, Whatcom, San Juan, and Island counties, and was itself formed from a portion of the huge Thurston County. Thurston County had been created by the Oregon Territorial Legislature in 1852 from the even-larger Lewis County, which predated Oregon Territory and was created in 1845 by a temporary government formed by settlers and known as the Oregon Provisional Legislature. The pattern of creating new counties by slicing parts from one or more older and bigger ones would continue in Washington Territory.

Counties Galore

The first session of the Washington Territorial Legislature met at Olympia beginning on February 27, 1854. Before it adjourned, eight new counties had been established. One of the first was Whatcom County, which was created on March 9, 1854. It was made up of the northernmost portion of the existing Island County and had as its northern boundary the U.S.-Canadian border at the 49th parallel.

On January 14, 1858, the Washington Territorial Legislature enlarged Whatcom County by adjusting its southern boundary, taking even more of Island County. Exactly three years later, on January 14, 1861, the legislature created Snohomish County from the remaining mainland portion of Island County, which was left with only two populated areas, Whidbey and Camano islands. In a perhaps unfortunate simile, one historian wrote, "The multiplication of counties ... is by a process of fission, like the propagation of polyps and other low orders of life" (Illustrated History, 127).

County Aspirations

The first public indication that moves were afoot to create a new county from the southern part of Whatcom County appeared in the September 15, 1883, edition of Anacortes's first newspaper, the Northwest Enterprise. It announced that "A petition is being circulated at Laconner and on the Skagit to divide Whatcom County. The line of division is to be on the Chuckanut mountains and running west between Cottonwood and Guemes Islands, bringing Guemes, Cyprus and Fidalgo Islands into the southern portion and making Laconner the county seat" ("Brief Mention").

This development brought down the wrath of the Whatcom Reveille, a newspaper in its first year of publication. As described in a history of the region published in 1906, the Reveille declared that "the north half of the county is neither dead nor sleeping and ... if the southern half invites a combat the north half will buckle on its armor and go in" (An Illustrated History ..., 127). According to the same volume, The Puget Sound Mail of La Conner then weighed in, rejecting "the arrogant assumption that the sun rises and sets in and about the town of Whatcom ... " (An Illustrated History ..., 127). (Besides being the name of the county, Whatcom was the name of one of four settlements that eventually consolidated to become Bellingham.)

But not everyone in the southern part of Whatcom County favored the idea of division, including the editor of the Northwest Enterprise. Even though Anacortes lay within the proposed new county, the November 17, 1883, issue opined, "The time for such a measure is premature. The county is still very sparsely settled, and such as have taken up their homesteads in the dense forests are poorly prepared to support two county organizations at the present time" ("Special Announcement").

The paper was not alone in opposing the very idea of a division, but many others were more accepting, or more resigned, and disagreed only on where the dividing line should be. Whatcom County boosters wanted the boundary to be between townships 35 and 36. Those advocating for a Skagit County argued that if the border was not at or north of the northern line of township 36, Whatcom County would have five tiers of townships to the new county's three. Moreover, the boundary would bisect the small community of Samish, divide Guemes Island in half, and pass through the Skagit River. While the sides were dueling in the local newspapers, the real action was getting underway at the territorial capital in Olympia.

Legislative Maneuvering

The Organic Act that established Washington Territory in 1853 created a Legislative Assembly that comprised a Council (the equivalent of a Senate) and a House of Representatives. This system remained intact in 1883. Whatcom County was represented on the 12-member Council by James Power (1844-1923), who also represented Island and Snohomish counties, and in the 24-member House of Representatives by Orin Kincaid (1821-1905), who also represented San Juan County. Both resided in the southern half of Whatcom County, and when the legislature met in the fall of 1883 both were given seats on the Standing Committee on County Matters.

Early in the legislative session Power introduced in the Council a bill to divide Whatcom County at a line between townships 36 and 37, thereby keeping intact the settlement of Samish and Guemes Island, both of which would be entirely within the proposed Skagit County. The loss of those areas was softened somewhat for the bill's opponents by an adjustment that left Samish Bay and Lummi and Eliza islands entirely in Whatcom County. Nonetheless, on October 24, 1883, the Council voted down the proposal by a margin of eight to four.

Kincaid, undaunted, introduced an identical bill in the House on November 15. It passed on November 24 by a vote of 11 to seven and was sent back to the Council, which on November 28 reversed itself and approved the measure by a vote of seven to five. The bill was signed the same day by Territorial Governor William A. Newell (1817-1901) and became law.

The legislative reversal was deemed due to the complacency of those who had most strongly lobbied against the new county. They had decamped from Olympia following the Council's October rejection, and in their absence the bill was "rushed through before they had time to find out what was in progress" (Illustrated History ..., 128). In its December 1, 1883, edition The Puget Sound Mail could not resist gloating:

"Verily, as our Whatcom contemporary has truly remarked, 'He laughs best who laughs last.' Wherefore do we cacchinate [sic] most audibly ... . Therefore the bill, having passed both houses, is now the law of the land; and we now live, breathe and have our material being in the county of Skagit, which same is in the territory of Washington" ("Skagit County, W.T.").

The Details

The statute creating Skagit County appointed a three-member board of commissioners to organize a special election for the second Tuesday of January 1884 to fill the various offices needed to govern a new county. Several Whatcom County officials, including "justices of the peace and constables" who had had jurisdiction over the county's southern precincts, were simply declared to henceforth be servants of Skagit County ("An Act to Create ... the County of Skagit," Sec. 3).

A special problem was the fact that the Whatcom County Territorial District Court was located in La Conner, which was now part of Skagit County. Because the population of the region was still so sparse there was no need for a second court, nor was there a need for additional legislators at a time when two or more counties were often represented by the same individuals. To get around this dilemma (and adding insult to Whatcom County's injury) Section 4 of the act read: "That the district court, now established and holding terms for the territory embraced within the present limits of Whatcom county, shall continue at La Conner as the district court for Skagit county; and the county of Whatcom is hereby annexed to said Skagit county for judicial and legislative purposes ..." ("An Act to Create ... the County of Skagit," Sec. 4).

Whatcom County commissioners would continue to govern Skagit County until the 1884 special election. Other provisions of the law dealt with such nuts-and-bolts issues as the division of tax revenues and the transfer of property records. La Conner was named the temporary Skagit County seat pending the general election in November 1884, at which time the new county's voters decided to move it to Mount Vernon, where it has remained since.

Whatcom County survived the amputation and was left intact thereafter, becoming the home of Western Washington University in Bellingham, while Skagit County developed as one of the most productive agricultural areas on the west side of the Cascade Range. More tulip, iris, and daffodil bulbs are produced there than in any other county in the U.S., and in the twenty-first century farming remains Skagit County's leading industry, producing more than $300 million annually in flowers, crops, livestock, and dairy products.