Anne Focke has been an integral player in Seattle's cultural life since she graduated from the University of Washington in 1967, one of the first graduates in the university's art-history program. She worked in the education department at the Seattle Art Museum; created arts programming for Seattle public television station KCTS-9; co-founded and/or (Seattle's first nonprofit alternative art space); and was a prime mover in the advent of Bumbershoot, the Seattle Arts Commission (later the Office of Arts and Culture), Artech, and 911 Media Arts Center. From 1999 to 2008 Focke served as the first executive director of Grantmakers in the Arts and was co-editor of its journal, the GIA Reader. Among the many enterprises she spearheaded were Artist Trust, a nonprofit supporting Washington state artists; Arts Wire, a national online network for the arts; and Penny U, a conversation series about work with Town Hall Seattle.

A Room of Her Own and Lots of People Around

As the one girl in a family of five boys, Anne Focke grew up with a strong herding instinct. "With my brothers ... I was either trying to organize them, which of course went nowhere, or make a storyline for their play, but they weren't interested; or I was trying to break up their fights, worried they were going to kill each other" (Farr interview). That desire to organize, direct, keep peace, and figure out how to make things work has motivated Focke's activities ever since.

Anne was born May 6, 1945, in San Antonio, Texas. Her parents Katherine (Kitty) Crawford Focke (1920-1997) and Alfred Bosworth Focke (1906-1986) were in the process of moving across the country from Washington, D.C., to California when they stopped over at Kitty's family home in Texas for the birth of their first child. Kitty stayed on for six weeks until she and baby Anne were ready for the rest of the trip, while her husband went ahead to California to set up house.

Alfred was a physicist with the U.S. Navy and head of the scientific team that would detonate an underwater nuclear device in the mid-1950s. Kitty was working as a secretary when the two met. The couple set off for California in 1945, when Alfred was hired to teach at Cal Poly. Alfred had a son, Alfred B. Focke Jr. (b. 1935), from his earlier marriage to Alice B. Cook, who had died.

The family, living in San Diego at first, expanded rapidly. Theodore William was born in 1946, Francis George in 1948, Karl Crawford in 1949, and Louis Ross in 1950. For a year, while Alfred worked at Point Mugu, the family lived in Ventura. In 1958, when he was hired as the head of the physics department at the new Harvey Mudd College, the Fockes moved to Claremont, where Anne attended Claremont High School. She had skipped a grade in junior high and was a little younger than the rest of her class. As Focke later recalled, this may have made sense academically, but socially it was difficult.

Life at home, however, was always brimming with people and activity. In the early 1950s, Anne's maternal grandmother, Alice Ross Crawford (1888-1978?) moved in to help with the children and for a while three orphaned cousins were also living with them. The household was packed, but as the only daughter, Anne had her own room, which she loved:

"It was a tiny little room, but we painted it pink and it had a couple of windows and if I couldn't see the ocean, I imagined I could see it ... We were up on Mount Soledad and then it was wide open spaces, sage brush, and flower farms and cactus ranches, dairy farms, open dirt roads, and mom would say 'Get out of the house,' and there'd be a bell to bring us back" (Farr interview).

That idyllic era of her childhood set a pattern for Focke. She unconsciously longed for a room of her own and lots of people around, and so, as much as possible, arranged her life accordingly.

To Seattle via Portland

It was in Anne's DNA to be a high achiever. She took piano lessons, twirled a baton, and organized the majorettes to march at football games (even though there was no school band.) She had an art teacher who encouraged her and in high school she won a competition for a scholarship to attend weekend sessions at Chouinard Art Institute. On Saturday mornings, Anne's mother would drive her to art classes there, which made her want to be an artist. She also took a summer drawing class at Scripps College before graduating from Claremont High in 1962.

When time came to consider colleges, Anne's parents wanted her to make her own decision. She studied catalogs and settled on Lewis and Clark, a private liberal arts college in Portland, Oregon. "It looked fun and had an overseas program and an art department" (Farr interview). The higher cost of out of state tuition was not a problem: One of Anne's uncles had given her some shares of stock, which she sold to cover her college bills.

Focke was attracted to psychology, political science, and philosophy and signed on for a six-month study course in Austria, led by a psychology professor. Her group immersed itself in German language studies and European history. That part of her Lewis and Clark College experience suited her. But back in Portland, the art department was a huge disappointment to a young woman who had already been exposed to top-notch classes at Chouinard and Scripps. In life-drawing class, rather than the standard nude model, the students were asked to draw a model in a poorly fitting one-piece bathing suit, Focke recalled. "I couldn't see what was going on at all, any of the bones, and I thought, 'give me a break'" (Farr interview). On top of that, the campus was isolated and bus service ended at 7 p.m., so Focke had taken to hitchhiking from town, which shocked her friends.

She decided it was time to transfer to a bigger school with more opportunities. She signed on at the University of Washington and eventually switched her major from art to art history. "My strategy for art history was: I really wanted to know why on earth I wanted to be an artist. And I thought maybe if I take it in order, old to new, I will figure it out" (Farr interview).

"Miss Anne Focke, Assistant in Education"

In 1967, Focke was initiated into Phi Beta Kappa and graduated magna cum laude from UW. She quickly found a job at the Seattle Art Museum (SAM) as assistant to Dorothy Lahr in the education department. "[Seattle Art Museum founder] Dr. Fuller was impressed by my Phi Beta Kappa," she recalled (Farr interview). Her art-history background served her well at the museum but, more than that, Focke came in with the kind of organizational skills and knack for public relations that drew immediate attention. "Miss Anne Focke, assistant in education" became a regular presence in the local newspapers. In January 1968, The Seattle Times reported:

"There is a peppy 22-year-old bustling through the quiet galleries of the Seattle Art Museum these days ... With switching long hair and bright mod dresses, she's taken the imagination of the youngsters who attend the art museum's classes. She just seems to have the knack — and the background — to interest them in things artistic ...

"She paints and draws herself, but not much or too seriously. Much of her spare time is devoted, in season, to skiing or tennis. Piano lessons are her latest interest" (Mahoney).

Keep in mind that that description dates from the era when newspapers still had a perky, segregated section of "Women's News" where women were generally identified by their husband's names and professions. As a young woman exiting college with an "artistic" career rather than a husband, Focke made good copy. The following year the Times devoted the entire front page of the Sunday Women's News section to Focke. It centered on a charming photograph of SAM's mediagenic assistant in education with her "Bright. Soft. Imaginative. Different" artworks. These were "soft cubes," square cushions made of vinyl, velvet, shag rug material, or fake fur, to be used as furniture or "strictly for decoration or fun" ("She Colors Them Bright"). One gathers this was just the sort of modern but nonthreatening thing a young career woman should be doing.

Old stereotypes were crumbling fast, though, and Focke was perfectly geared to navigate the shifting terrain. Her curiosity about art in all its manifestations and her ability to translate it to others in an easy, accessible manner smoothed the way. With her long hair and stylish clothing, she looked hip but still well-groomed and professional. Soon she was hosting some of the museum's arts programming on KCTS Channel 9. During this time she became friends with the unconventional arts patron and kindred spirit Anne Gerber (1910-2005). The two women both found joy in advocating for art and artists.

Meanwhile she had cut back to part time at SAM and had taken a job as assistant director of the Seattle Arts Commission. And she had entered a relationship with the artist Rolon Bert Garner (1940-2015), at the time SAM's preparator -- the person who designs and installs exhibitions and handles the delicate crating and moving of artworks. Garner was a force of nature: wildly energetic, off-the-wall creative, hardworking, and hard-partying. "Nature took its course," Focke said (Farr interview). She and Garner shared a house with the artist Robert (Bob) Teeple (b. 1941) and his first wife Barbara.

Networking and Brainstorming

Networking and brainstorming were Focke's strong suits. At Channel 9, she got to know the director of the SAM segment, Ron Ciro. "At a certain point I said, 'Hey Ron, there's more to art than just what the museum is doing. Let's do something'" (Farr interview). He agreed. So she began working with cameraman Gary Harper at KCTS to film interviews with local artists.

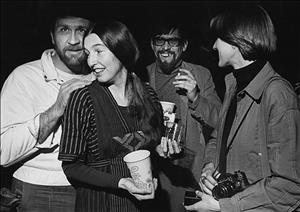

One of her shows, on March 29, 1970, featured five movers from the local art scene, all pals of Focke -- Garner, Teeple, gallery owner Jim Manolides (1930-2016), conceptualist Don Scott, and ceramist Fred Bauer (b. 1937). For Focke, this kind of interaction, possibly with less-than-helpful participants, was familiar turf. Here she was, herding five guys, just like she had done growing up!

"She really enjoyed working with males," said Seattle artist and former colleague Ken Leback (b. 1941). "She grew up with brothers and that was a training ground for how to make these things get along and move along" (Farr interview).

Focke also became deeply involved in the women's movement, especially through her connection to curator and art critic Lucy Lippard (b. 1937). Focke met Lippard in 1969 at the Seattle Art Museum while Lippard was orchestrating the hard-to-categorize conceptual exhibition titled "557087." Focke recalled:

"Nobody knew how to deal with that one, right, because it was digging holes and getting logs and taking photos every day, and measuring precipitation in a tube, collecting Vito Acconci's postcards and putting them on the wall: all these things ... But then through Lucy ultimately I got to know a lot of other people, so it was just a really important connection she and I made at that time" (Farr interview).

One of those connections was with the women's artist network called West East Bag or WEB, a pre-internet method of staying in touch with other artists around the country through circulating newsletters.

Working with Lippard, Focke got acquainted with administrators at Seattle Center and with Seattle mayor Wes Uhlman (b. 1935). Her charm and competence were quickly noted. Focke was recruited to help organize Festival '71, the precursor to what became the annual summer music and arts festival Bumbershoot. She was given charge of one fifth of the festival budget, the to-her-huge sum of $5,000, to assemble exciting arts programming. She did.

Focke was in 1972 hired as assistant director of the Seattle Arts Commission (now the Seattle Office of Arts & Culture.) In 1973 she cut back to half-time and became the first director of the City of Seattle's Arts in Public Places program. She implemented the newly passed 1 Percent for Art ordinance, which set aside 1 percent of city capital-improvement-project funds for public artworks.

Laying the Groundwork

In 1973 Focke and Garner took a trip to New York, where Focke discovered the alternative art space the Kitchen, then located in the Mercer Arts Center. La Mama Theater was one of many groups then housed in the building, along with a bar and boutique. Seattle had nothing like it and Focke's imagination sparked. She remembers thinking: "Let's just do it."

Later, on a road trip to a design conference in Aspen, Colorado, with some of her buddies, Focke began laying the groundwork. She was traveling with Garner, Teeple, and Leback, and they would be joined in Aspen by artist Don Scott. As a group they had dubbed themselves, with tongues firmly in cheek, the Seattle Souvenir Service, and together and individually participated in various art projects, including collecting and displaying Space Needle memorabilia. Along the beer-fueled drive to Aspen, Focke started tossing out possibilities for new arts venues and asking the guys for their ideas and input. "She's pretty good at charming people," Teeple recalled (Farr interview).

The result of that road trip was and/or, Seattle's first nonprofit artist-operated alternative art space.

"In that conversation we really created the form for and/or: What do we call it? What's our goal? Most of it was driven by Anne and, for the rest of us, self-interest," recalled Leback, who was recruited, somewhat reluctantly, to be on the board. "She was the only person in the group who would go the next step and say, 'How do we contact this person?' We had the ideas but no follow-up," (Farr interview).

and/or

In April 1974, and/or opened its doors to the public at 1525 10th Avenue in Seattle's Capitol Hill neighborhood. The small original governing board consisted of Focke, Garner, Leback, Gerber, and Jerry Jensen. The gallery space was open three days a week, plus occasional evenings for scheduled events, and was devoted to the presentation of artworks "including videotape, film, conceptual work, contemporary performance, publications, multi-media situations and other work ..." ("What was and/or?").

The concept was a work in progress. Focke directed the nonprofit, taking charge of fundraising, finances, personnel, long-range planning, and community relations. In addition, she herded her cohorts, who included Garner, as visual-arts director; Annie Grosshans, publications; David Mahler (b. 1944), music; Ann Obery (b. 1949), library; and Norie Sato (b. 1949), video. Through Focke's connections and the exciting programming vision she presented, the National Endowment for the Arts took an interest and provided funding.

The exhibitions and events ranged from playful, moving, and exuberant to outrageous and totally off the wall, bringing to Seattle nationally known artists including Laurie Anderson (b. 1947), Robert Bly (b. 1926), Judy Chicago (b. 1939), Meredith Monk (b. 1942), Nam June Paik (b. 1932), and many others. Perhaps more importantly, it gave a host of Northwest artists a venue where they could respond and play a part in the broader arts community.

It was just what Seattle needed at that transitional moment in art history, when new media, performance, installation, and conceptual art were pushing artists down unexplored avenues. Often the results were temporary and unsellable. For the most part, the city's commercial galleries weren't suitable venues for such work, so and/or gave artists a place to try out new ideas.

Focke described the activities, exhibitions, and visiting artists as well as the evolution of and/or in an essay originally published in a chapbook and reproduced on HistoryLink.org.

Long torn between her desire to be an artist and her desire to organize, promote, and enable artists, Focke responded to a 1978 invitation to participate in a show at the Portland Center for the Visual Arts not with visual art, but with writing in a grid on the wall. She described the work to a reporter as a consideration of her own "internal and personal relations with power and control, to relatively practical considerations of the operation of an organization, primarily And/Or," ("Appel Paints Potent Emotions").

That same year Focke was included on the list of Time magazine's "Newsmakers of Tomorrow."

It turned out that as an organization and event space, and/or was fairly short-lived. There were rumblings of change by the early 1980s, in 1981 the exhibition program ended, and then in 1984 -- shortly after and/or had received a Governors Arts Award and an $85,000 NEA grant -- Focke announced that and/or was closing its doors. "The timing couldn't be better," Focke said of the grant money, "It dovetails with our plans for future development" ("And/Or, Graywolf Get Endowment Grants").

Creating Art Organizations

Because of the way and/or's structure had evolved -- with separate divisions under the leadership of different people -- Focke proposed releasing the various divisions as independent entities. Artech Fine Arts Service had already spun off in 1977, designed around Garner's well-regarded skills. Focke and Garner ended their relationship about that time and shortly after that Focke and composer David Mahler became a couple. Under and/or's umbrella, Mahler initiated Soundwork, a center for composers and sponsor of new-music concerts. Other divisions that spun off were Focal Point Media Center and the library, which later merged as 911 Media Arts, with leadership from Claudia Clement, Heather Dew Oaksen, Jill Medvedow, Norie Sato, and others.

In 1986 Focke recruited her old UW classmate David Mendoza and with him co-founded Artist Trust, a nonprofit organization to support Washington artists. With Focke unready to step back into a leadership position so soon, the board, led by Thatcher Bailey (b. 1954), hired Mendoza as the director.

Always conflicted about how to define herself, Focke, at a certain point, began to take a more encompassing, Zen-like attitude to art and the many ways creative energy can manifest itself. Patterns and systems interested her. And just as artists had taken to considering conscious actions, even sweeping the floor of the gallery, a type of artwork, Focke began to see creating organizations that allowed art to happen as satisfaction enough. "I probably maintained some identity as an artist inside myself, but I didn't try to relate it to what was going on in the art world, to make a connection" (Farr interview).

After and/or closed, Focke was approached about applying for the head curatorial post at the newly founded Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. She also considered coordinating a new music festival in Texas. But instead, for the next 15 years, Focke chose to remain a free agent. She served as arts advisor for the 1990 Goodwill Games in Seattle and for AIDS Housing of Washington. She was hired as a planning consultant for the Seattle Arts Commission and the King County Cultural Resources Division, as well as Centrum, the Bush Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and others.

Focke had a business card printed with just her name and contact information. "It was hard for me to say 'consultant,' though I sometimes did," she later wrote. "The word sounded so 'hit and run,' coming in to advise and then leaving, not hunkering down and really making something work in the world" (Focke, 16).

Anne Focke Carries On

All the while, she continued promoting her own projects and ideas. In 1989, working with the New York Foundation for the Arts, she organized a national conference, "Creative Support for Creative Artists." The desire to keep up the conversations begun there led Focke to initiate Arts Wire, an early national computer network and news service for artists and the arts, which she co-directed until 1995. Meanwhile she had begun co-editing the journal GIA Reader, a publication of Grantmakers in the Arts, a national association of private, corporate, and public funders. In 1999, she took over as first Executive Director of the organization, after helping plan the shift from it being a board-run entity to having a professional staff.

In 1997, after living together for nearly two decades, Focke and Mahler married. Four years later they separated, and in 2002 divorced. Typically, Focke felt the need to share the closure of that long relationship with her friends and community. She organized a "release ceremony," which involved writing an open letter and inviting friends to join her in writing about release. With the 50-plus replies she got from people around the country, she and her old friend and colleague, artist and designer Tommer Peterson, made a book. Focke remained close to Aviva Mahler DeLancey, David's daughter from a previous marriage, Aviva's husband, Brian DeLancey, and their children Livia Rose (b. 2010) and Henry Elsworth David (b. 2015), whom Anne considered her grandchildren.

Focke resigned from her post at Grantmakers in the Arts in 2008 but remained involved with art, culture, and politics through her freelance work and her blog "Anne Focke carries on." The Anne Focke Gallery in Seattle's City Hall was named in her honor, to acknowledge the widespread and enduring contributions Focke has made to Seattle's arts community.