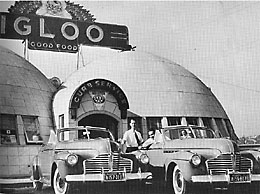

The Igloo, a diner and drive-in restaurant at the southeast corner of 6th Avenue and Denny Way, operated from late 1940 until sometime in 1954. It featured a distinctive twin-domed design intended, like much vernacular commercial architecture of its period, to grab the attention and business of passing motorists. The Igloo was established by Ralph Grossman and Ernie Hughes, and later managed by Sander's Fountain Lunches.

According to telephone directory listings and other data, the Igloo opened for business in 1940. Located at the Denny Way ramps to and from Aurora Avenue -- then Seattle's primary north-south highway -- the eatery's pair of metal-clad "igloos" and ice-blue neon sign enticed travelers and locals alike.

Burger Joints and Pie Palaces

Such whimsical "vernacular" (non-professional) roadside architecture in America was a byproduct of the Automotive Age. By the 1930s a vast network of roads and highways connected every state in the nation, dotted with ubiquitous diners, motels, and gas stations. Auto-dependent entrepreneurs competed by resorting to ever more outlandish structures and garish signs. Local examples of such "auto-tecture" include the Twin Teepees on Aurora Avenue near Green Lake (demolished in 2001) and the Hat 'n' Boots gas station on East Marginal Way in Georgetown.

Modern and inexpensive construction techniques aided in such pop-culture architecture. Throughout the mid-century, oddball buildings popped up everywhere from coast to coast. Burger joints and pie palaces across the nation were built to resemble big peanuts, large coffeepots, gigantic oranges, monster hotdogs, and a host of other bizarre, non-traditional shapes. For many restaurant owners, getting passersby to bug out their eyes was the first step of luring them inside.

In Seattle, entrepreneurs Ralph Grossman and Ernie Hughes took note of this nationwide craze when they planned a new diner overlooking the busy intersection of Aurora Avenue and Denny Way. After ruling out many designs that they felt to be too ordinary, Hughes came up with the concept of building it in the shape of an igloo. Better yet, two igloos.

Groundbreaking commenced on Halloween day, 1940. Construction started on what would become two side-by-side hemispheres joined by a stereotypical igloo "tunnel" which served as the main entrance. The buildings were made out of metal and each was encircled by a ring of windows. Topping it off was a large neon sign depicting a smiling Eskimo above the diner's name, with the enticing, ever-popular "Good Food" slogan beneath.

Knowing that diner clientele of the era were predominantly male, Grossman and Hughes scoured the city looking for attractive young women to work as waitresses and carhops. Visiting downtown office buildings and local movie theaters, they persuaded a bevy of pretty, but underpaid, usherettes and elevator operators to come and work at the new diner. Like former Igloo waitress Irene Wilson, many jumped at the chance for better pay and a more enjoyable job.

Carhops at the Igloo wore short flared skirts, a white jacket, and white cowboy boots and served orders on trays that hooked to customers' half-open car windows. During the wintertime, they wore fashionable ski togs from Nordstrom's department store. Dining room waitresses sported aprons festooned with blue dots while tending to as many as 70 customers at a time.

The Locals Liked It

Although the Igloo was a roadside diner meant to lure hungry travelers, repeat customers were predominantly locals who worked nearby. At the time, the area south of Lake Union was filled with small businesses and industries that employed hundreds of workers. Each day at noon, many of these employees would stop over at the Igloo for deluxe cheeseburgers, double-malteds or a sack of onion rings. Sometimes after work, the Igloo was a convenient spot to meet with friends.

Throughout the 1940s, the Igloo was a standout landmark on the northern outskirts of downtown Seattle. When a friend called with an invitation to meet over a Husky Burger and an ice-cold Boeing Bomber, people knew exactly where he was talking about. Postcard images of the diner would sometimes be sent to old pals who had moved away. The Igloo was also a popular hangout for local police officers.

Increased competition and changing economics led the owners to seek out new business opportunities. Ralph Grossman, a car buff since his days before the Igloo, left to run an automobile dealership. Ernie Hughes, along with his wife Dorie, went on to operate the Doghouse, another well-remembered Seattle eatery.

The 1953 and 1954 telephone directories list The Igloo as operated by Sander's Fountain Lunches. The restaurant is not listed in the 1955 directory and appears to have been demolished by 1960. Decades have passed since folks pulled up in their jalopies and sedans, but for many former patrons, the restaurant's name still triggers memories of burgers on the grill, perky carhops, and steaming cups of joe in a warm, friendly joint incongruously called The Igloo.