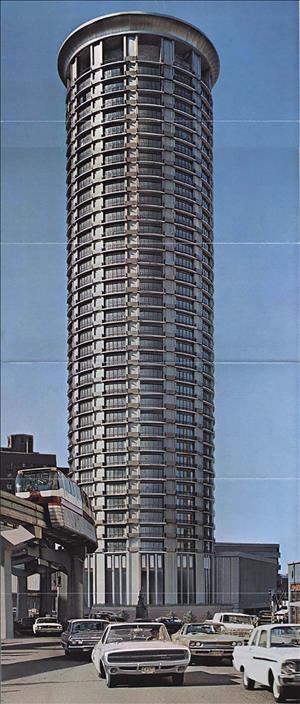

On June 29, 1969, the Washington Plaza Hotel opens in Seattle on the site of the old Orpheum Theatre. It is the first luxury hotel built in downtown Seattle since 1929. The hotel is located at 1900 5th Avenue.

Making Plans

Plans for the Washington Plaza Hotel were announced on December 28, 1966, by Eddie Carlson (1911-1990), president of Western International Hotels. Earlier plans called for an arc-shaped, 22-story addition to the Benjamin Franklin Hotel, located on the site of the Orpheum Theatre. When the costs of building an addition became prohibitive, Western International decided to build a completely new hotel.

Calrson explained that the Washington Plaza Hotel would be a 39-story, circular hotel, joined to the Benjamin Franklin and providing a total of 728 rooms. The 386-foot tower would contain 442 guest rooms served by three passenger elevators and two service elevators. Public facilities, including a cocktail lounge and a Trader Vic's restaurant, would be on the first three levels, and a common lobby for both the Washington Plaza and Benjamin Franklin would be on the second level. The first level included a motor entrance. A seven-level parking garage would adjoin the building

Initial cost for the project was $18 million. John Graham & Associates, who designed the Space Needle for the 1962 Seattle World's Fair, were the architects for the hotel. The Howard S. Wright Construction Company, builder of the Space Needle, was the general contractor. Interior design was by Western Service and Supply Co.

The Curtain Falls

Before the hotel could go up, the Orpheum Theatre and an old parking garage had to come down. On June 26, 1967, a two-day auction was held at the venerable old theater, and everything was up for grabs -- film projectors, art work, furniture, and even plumbing fixtures. On hand to bid the theater farewell were B. Marcus Priteca (1889-1971), the Orpheum's architect, and orchestra leader Charles "Tiny" Burnett (1888-1974), who had been there in 1927 for the theatre's opening.

Once the Orpheum was picked clean and was ready for demolition, Western International Hotels marked the beginning of construction with a balloon launch from the future hotel site. From the roof of the Benjamin Franklin Hotel, Eddie Carlson raised a giant balloon to 386 feet, marking the new hotel's height. At street level, 1,000 helium balloons were released. Some contained dinner tickets for anyone lucky enough to find one.

The Orpheum came under the wrecking ball on August 6, 1967, and was completely gone by October. The hole for the hotel's foundation was dug soon after, and workers began pouring concrete by the end of the year. Over 2,500 cubic yards of concrete was used for the foundation.

Towering Above

Work started on the hotel's core in January, 1968, but by spring a steel fabricators strike slowed construction. In May, work stalled just as the fifth floor was being built, and construction didn't go back into full swing until after the strike was settled in July. The Spring 1969 opening of the hotel was pushed back to June.

Slowly but surely, the hotel rose, a floor at a time. On January 15, 1969, a "topping off" ceremony was held, marking the final hoist of steel used in the building's shell. Standing atop the tower, Eddie Carlson spoke to about 60 invitees willing to brave the cold weather. The highlight of the ceremony was the placement of a royal crown atop a three-foot-tall model of the hotel.

During construction of the tower, the Benjamin Franklin Hotel -- known to many locals as "The Ben" -- was getting a facelift of its own. Built in 1929, the Ben was brought into the modern era with new paneling, carpets, and other accoutrements so that it would be a worthy partner to its new neighbor.

Western International Hotels took out full page ads in the local papers explaining that the Benjamin Franklin Hotel wasn't going away, but would be an integral part of the entire project. The ad stated, "We're calling the "Ben" part, the plaza. And we're calling the "tower" part, the tower (The Seattle Times, April 4, 1969). The ad also described some of the new amenities that people could look forward too, including the Plaza Ballroom and the Westlake Room supper club, with live music and dancing. The Rib Room (renamed a few weeks later as the Beef Room) would be the place to go for fine dining, cocktails would be available in the Plaza Library, and an enlarged Trader Vic's would provide a "gourmet escape to the South Seas."

The Seventh Wonder

A week before the hotel opened, the Westlake Room announced upcoming shows that had already been booked for Seattle's newest night club. Gordon MacRae was the first headliner, followed a week later by singer Jaye P. Morgan. Other acts throughout the summer included Billy Eckstine, Abbe Lane, Shari Lewis, Eartha Kitt, and the Four Freshman. The Westlake Room could seat 210 guests, and the cover charge was $3.50.

The final days before the opening were hectic. More than 400 people had been hired for work at the new hotel, and many had been in training sessions since June 1. Interior decorators scrambled to hang chandeliers, place art work, and make sure that everything would be clean and spotless. Employees and their spouses were invited to spend a night at the hotel before it officially opened, to evaluate services and operations.

On the day of the opening, Western International Hotels took out another full page ad in the papers, proclaiming the Washington Plaza Hotel as one of Seattle's seven great wonders. The ad copy stated "In our opinion, the others are Woodland Park Zoo, Pike Place Market, the Monorail, the Space Needle, the domed stadium (when it's built), and the Olympic Hotel (because it's another Western International Hotel and a perfectly marvelous place."

The guest rooms were full on opening day. Shriners from across the country were in town for their annual convention, and although most of their meetings took place at the Olympic Hotel, the fez-wearing funsters filled both hotels.

The new tower, combined with the Ben Franklin Hotel, offered 715 guest rooms and suites, 11 meeting and conference rooms, a grand ballroom, bars, restaurants, and parking for some 300 cars. In 1981, the Washington Plaza Hotel was renamed the Westin Hotel. A twin tower, the north tower, was completed in 1982. The north tower, which replaced the Benjamin Franklin Hotel, is 449 feet high and has 44 stories.