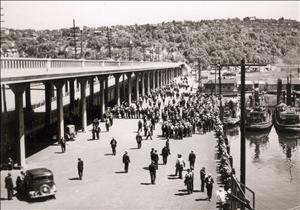

On May 9, 1934, 1,500 Seattle Longshoremen join 12,500 other maritime workers in closing every seaport between San Diego and Juneau. It is the first industry-wide strike on the West Coast. The strike comes after steamship companies refuse to negotiate with the Longshoremen over the issues of representation by the International Longshoremen's Union, a union-controlled hiring hall, closed shops (all employees are represented by one union), higher wages, and shorter hours. The maritime unions such as the Masters, Mates and Pilots, the Cooks and Stewards, the Seamen, and the Marine Engineers join in, and all the unions agree to stay off the job until settlements are reached with all of them.

The strike continued until July 31 when the Longshoremen voted to turn the dispute over to federal arbitration.

In Seattle, shipping companies recruited unemployed men including African Americans as strikebreakers and enabled these strikebreakers to avoid crossing picket lines by moving workers to docks and by housing them aboard ships. When 100 University of Washington students were recruited as strikebreakers, the University president denied the shipping firms access to the University's wharf.

A Costly Strike

Police in Seattle battled strikers with clubs and tear gas, and a police tear-gas canister killed a striking sailor at Smith Cove. A Longshoreman was shot to death at the Point Wells fuel terminal north of the city. A Special Deputy Sheriff employed "for special work by the citizens' emergency committee" was also killed. Two University of Washington students died in a lumber loading accident. In San Francisco, police shot two men, triggering a three-day general strike. In Los Angeles, police killed two strikers and wounded 21 strikers.

Better Conditions Were Obtained

Federal arbitrators decided most issues in favor of the Longshoremen, including an end to the "shape-up" where men waited at docks every day to be picked for work. The union and the shipping companies began to run a hiring hall jointly where all union members had equal opportunities for work. Wages increased and the dock workers got a six-hour day and a 30 hour week.

As a result of this strike, African Americans, Filipinos, and other non-whites were admitted to the maritime unions on the same basis as whites, ending their exploitation as strikebreakers. During the strike, blacks served on strike committees and on staff picket lines.