From 1907 to 1913, a glittering jewel lit up the night along the northern tip of West Seattle. A person in downtown Seattle could look across Elliott Bay and see a myriad of lights dancing and playing across the waves. On a summer night, if the air was very still, the faint scream and clatter of a roller coaster and whispers of calliope music could almost be heard. If such wondrous sights and sounds enticed, a short ferry ride was all it took to be magically transported to Luna Park, the Coney Island of the West.

On the Flats

Luna Park was built on the tide flats along Duwamish Head, not far from where Seattle's first settlers landed in 1851. By the turn of the century, Seattle had become a burgeoning metropolis, and West Seattle was a city in its own right. Not wanting to be overshadowed by the big city next door, the West Seattle city council agreed that their town should be home to "the greatest amusement park in the Northwest." Construction began in 1906, headed by easterner Charles I. D. Looff. Pilings were driven deep into the tide flats to allow the park to be built out over the water. In this way Luna Park was very similar to Coney Island and many other amusement parks built in America at that time.

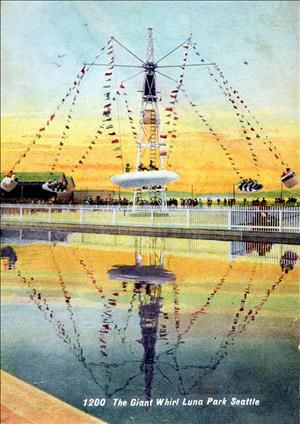

Rides and amusements crowded the pier. Among them were the Figure Eight Roller Coaster, a Merry-go-round, Chute-the-Chutes, the Water Slide, Cave of Mystery. and other funpark standards. The Canal of Venice, The Original Human Ostrich, The Joy Wheel, and Infant Electrobator were some of the others. During hot summer days, swimmers could paddle and splash at the Salt Water Natatorium, which had both fresh and salt water swimming pools. At night, the Dance Palace was a popular place for a young fellow to bring his gal and dance by the light in her eyes.

Another enticement of Luna Park was the best-stocked bar on Elliott Bay. Unfortunately, for West Seattle residents this proved to be a detraction, not an attraction. Angered that their city council would allow their community to be overrun by "boozers from Seattle," they petitioned Seattle to annex them.

Luna Park and the Demise of West Seattle

In 1907, Seattle was in the throes of moralism. Mayor William Hickman Moore (1861-1946), a judge who vowed to keep Seattle clean from unnatural vices, was just what West Seattleites felt they needed to keep their community upright and rigid. On June 29, 1907, two days after Luna Park opened for business, they voted 325 to 8 for annexation, and the City of West Seattle ceased to exist. Not that it did much good. Also annexed in the election were Ballard, Columbia City, and Rainier Beach. The City of Seattle had a lot more to think about than wagging fingers at a few drunks. As the city dads grappled with growth and expansion, Luna Park and its "longest bar on the bay" was mostly left alone, and proved to be quite the attraction it was planned to be.

Three years later, a new Mayor, Hiram Gill (1869-1919), entered the scene. By this time, many folks all over the city were fed up with city officials trying to legislate morality. They elected Gill in the hope that he would open up the city. That he did, and this enraged the "morals squad." A group calling itself the "Forces of Decency" demanded a recall vote. Made up of prohibitionists, progressives, and newly enfranchised women voters, they went on a self-righteously indignant crusade. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer added fuel to their ire. A January 31, 1911 newspaper article contained accusations that at "Sunday night dances at Luna Park ... girls hardly 14 years old, mere children in appearance, mingled with the older, more dissipated patrons and sat in the dark corners drinking beer, smoking cigarettes and singing."

On top of bad press like this, W. W. Powers, manager of Luna Park and a Gill supporter, also got caught up in Gill's biggest scandal. The Mayor had allowed his chief of police, Charles Wappenstein, to build a 500-room brothel on Beacon Hill. Powers, as reported by the P-I, was a shareholder in the "corporation" formed by Wappenstein and his cohorts.

Fading Away

Under the gloom of muckraking and scandal, the jewel of West Seattle began to fade. In 1913, Luna Park closed, and its rides and amusements were sold or torn down. No more glittering lights on Elliott Bay, no more strains of calliope music on summer nights. All that remained was the Natatorium, which drew swimmers for the next two decades. On April 14, 1931, an arsonist lit a match to it, and in one final conflagration a flame brighter than all the lights of its glory days turned what little remained of Luna Park into only a memory.

Except for one thing. Approximately once a decade, the tides of Elliott Bay fall back to their lowest levels. When they do, the tide flats are exposed and the rows of pilings that once supported Luna Park are brought to light, causing new generations and new residents of the Northwest to gaze and to ponder. Then the high tides return, and once again Luna Park fades into the past.