Imagine life without telephones or e-mail; without automobiles, motorboats or airplanes; without floating bridges or paved roads over the Cascades. So it was in 1900. Seattle boasted some of the nation's first dedicated bicycle trails but paved roads were rare and Seattle had exactly one automobile (an electric one at that). Most citizens relied on their feet, horses, and streetcars to get around the city, and they took trains, interurban railroads, and Mosquito Fleet steamers to reach more distant points in the region. As for communication, the telegraph linked Seattle to the outside world. Telephones were novelties and most residents and businesses relied on the Post Office and on couriers for their local communications. It was all extremely slow and cumbersome by today's standards, yet, with their primative tools, the people of 1900 were able to build a great city. Historian James R. Warren (1925-2012) takes us back to this calmer time in this special essay, adapted with permission from the Puget Sound Business Journal.

Velocipedes and Horseless Carriages

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, most people walked to their destinations or rode astride or in a carriage behind a friendly steed, or took a streetcar, or pedaled chain-driven bicycles, which arrived in the 1890s. By 1900 more than 40 Seattle firms were selling models ranging in price from $25 to $150. Bicycle clubs attracted hundreds of members and miles of bike trails were maintained throughout the area. Mayor George Cotterill (1865-1958) championed the development of some of the first bike routes ever built by an American city.

The first automobile, a Wood's Electric, arrived in Seattle in 1900. It belonged to Ralph Hopkins, former president of Treen Shoe Co., who drove it cross-country from Chicago to Seattle. The silent, thin-tired vehicle maneuvered with difficulty on the muddy streets, so Hopkins sometimes drove on the wooden sidewalks. Pedestrians dodging out of his way invariably shouted: "Get a horse!" In the entire United States in 1900, fewer than 8,000 automobiles existed. Puget Sounders of the time gave low priority to surfacing roads for these horseless carriages, which were considered a rich man's toy. The old Snoqualmie wagon road, the only trail to Central Washington, was little used after railroad tracks were extended through the mountain passes in the 1880s. The road soon became overgrown and impassible except for cattle drives, and was not opened permanently until 1915. It was not paved until the 1930s and remained closed during winters until 1931, when road crews began to use snowplows.

Riding the Rails

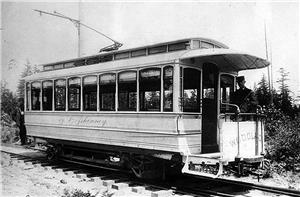

In 1883, Frank Osgood hitched a horse to a simple streetcar that rolled on rails up 2nd Avenue. By 1900, this service had converted to electric power. Cable cars, with the help of counterbalances, ascended Queen Anne Hill and the steeper grades of the Yesler Way and Madison Street routes to Lake Washington. As the new century began, the Stone & Webster Co. amalgamated 22 smaller independent streetcar companies into an integrated system. It later took over and extended fledgling interurban rail lines to link Seattle with Tacoma and Everett. (The City of Seattle bought the local streetcar system in 1918, and operated it until 1940.)

Citizens of 1900 depended on the railroads for speedy and comfortable overland travel. Rail service had been available in Seattle on a regular schedule only since 1893, when the Great Northern completed its line from Minnesota to Elliott Bay. To Seattle's great disappointment, the Northern Pacific chose Tacoma as its Puget Sound terminus in 1873 and provided only irregular branch-line service to Seattle after 1883. However, by 1911, four transcontinental rail companies served the area, including the Union Pacific, the Great Northern, the Northern Pacific, and the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul.

Ships of the Sea and Air

As the century was beginning, Puget Sound's historic water transportation system continued as a major mover of merchandise and humankind within and beyond the region. Forty-eight water transport companies are listed in the Seattle City Directory of 1900, several of them providing the small vessels of the "Mosquito Fleet" that flitted from settlement to settlement on all parts of Puget Sound.

Larger ships out of Seattle carried goods and passengers up and down the coast from California to Alaska. These companies were instrumental in maintaining Seattle's ranking as the leading Northwest seaport. The single foreign line listed in 1900 was Nippon Yusen Kaisha of Japan.

As the new century dawned, Puget Sound residents had not yet seen an airplane. In fact, the prediction that man would someday fly usually produced a derisive snort. It took the Wright Brothers' historic 1903 flight in their motor-driven, heavier-than-air machine to quell the doubt. The first powered dirigible was not demonstrated in Seattle until 1909, and the first airplane did not fly the Seattle skies until 1910. (Bill Boeing did not take his first airplane ride until 1914.)

Whispering Wires

The telegraph wire reached the village of Seattle in 1865 almost by chance. After an attempt to lay an undersea cable across the Atlantic Ocean had failed, a second plan was activated that would extend the wire to Alaska and across the Bering Strait to Siberia, then overland to Europe. However, after a second Atlantic cable effort succeeded, the route through Alaska and Siberia was abandoned. Luckily, by then the wires extended through Seattle and Seattleites received news of the final Civil War battles within hours rather than months later by mail from the East Coast. The Seattle City Directory of 1900 lists four telegraph companies, the largest being Western Union.

As the century turned, telephones were still in the early development stage in the Northwest. Seattle's original Sunset Telephone Exchange, installed in 1884, provided sporadic service. After the company increased its customer base and a competitor appeared, service improved. Because there was no connection between the two competing companies, most businesses in 1900 patronized both in order to communicate with all their customers.

The U.S. Postal Service remained the most commonly utilized communication link. At the turn of the century, every hamlet and crossroad boasted of its own post office, where a letter could be mailed for 2 cents per ounce. Newspapers and periodicals were posted for a penny a pound. In-city residents and businesses enjoyed several mail deliveries a day, and also used runners to send urgent messages.