On May 5, 1893, the New York stock market tumbles, setting off a panic that sweeps across the United States and crashes onto the Pacific Northwest. King County and the Puget Sound region plunge into a deep economic depression that lasts four years. Among the big losers are Peter Kirk (1840-1916), David Denny (1832-1903), and his wife Louisa Boren Denny (1827-1916).

The Boomingest Place on Earth

During the three or four years following the Great Seattle Fire of 1889, promoters were calling King County and the Puget Sound region "the boomingest place on earth." They may have been exaggerating, but if so, only a tad.

In 1887, the United States was coming out of a four-year depression. King County had been developing slowly. It had taken 36 years for 16,000 residents to settle within the confines of the county. That slow steady growth was about to make a tremendous spurt. As an incentive to build a transcontinental railroad, the United States offered the Northern Pacific Railroad half of the land along an 80-mile-wide strip along the railroad tracks. With a good economy and an enormous push from the Northern Pacific land promotion department, droves of settlers headed for Western Washington. Between mid-1887 and mid-1889, King County received about 900 new arrivals a month. In just a year and a half, the county's population had doubled.

The Great Fire

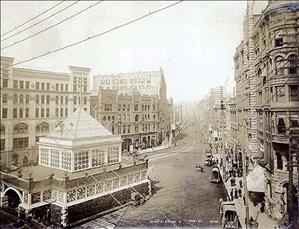

And then the population really exploded. In June 1889, Seattle's Great Fire destroyed the business district. Virtually before the embers had died, swarms of people began converging on Seattle seeking good paying jobs. For the next year, job seekers and their families arrived in the city at a rate of 2,000 a month. In one year, Seattle's population exploded from 26,740 to 42,837 people. This growth continued into the early 1890s.

The area strained to accommodate the swarms of new arrivals. Residential plats were developed, roads were cleared and graded, water mains were laid. Sawmills and brickyards were started and/or expanded to provide building materials for hundreds of new apartments and houses. Trolley lines were built to transport people to their newly built "distant" homes. Farmers had to clear land to grow additional crops and graze livestock to feed the thousands of arrivals. Coalmines were expanded to warm them. New schools and churches were built to educate and to give spiritual guidance. Dozens of "fireproof" buildings -- business, hotel, and retail -- were constructed to rebuild the post-fire downtown.

Local developers, investors, and capitalists could not have raised the enormous amount of money needed to rebuild and to expand Seattle and King County. No problem. Money poured in from San Francisco, the Eastern United States, and even from Europe. Almost anyone who wanted a loan could easily get one.

"The boomingest place on earth" took off. For six years development and construction continued unhindered. Some developers built not only for present needs, but anticipated further throngs that would surely pour in during the following month or year. Of course, speculators pushed up prices by buying acreage and block after block of platted property.

Boom to Bust

Then it happened. On May 4, 1893, the National Cordage Company, a group of rope manufacturers, failed. The following day the stock market declined dramatically. A panic began and it galloped across the United States.

An economic panic is fear: Bank depositors fear that banks will fail and that they will lose all or most of their savings. Depositors rush to their banks to withdraw their savings before the bank collapses. The bank, however, has lent out most of its deposited funds. If too many depositors line up to withdraw cash, the bank's funds are depleted, and the bank is forced to close. (In 1893, the United States government did not guarantee bank deposits.) Hundreds of banks across the United States failed.

The Banks Go Down

Within a year, some 11 Seattle banks went out of business. By the end of the depression, 14 of Seattle's 23 banks, plus all three King County banks outside of Seattle (Auburn, Kent, and Ballard) were forced out of business.

The Seattle banks that survived had a tough time. For instance, the total deposits of the Dexter Horton Bank, predecessor of Seattle First National Bank (in 1999 Bank of America), dropped from $1.2 million in May 1892 to $638,000 in May 1897. The First National Bank dropped from $229,000 to $72,000 during the same period.

Seattle banks, out-of-state banks, and investors who made loans in King County were desperate for money. They called in their loans. Once the flow of loans stopped, development and building was greatly retarded and the spiral continued downward into a depression. People stopped moving to Puget Sound and Puget Sound exported few goods. Except for the Great Northern Railway, all the major railroad lines that passed through King County failed and went into receivership, including Northern Pacific, Oregon Improvement Company, and Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern. In Seattle and King County, of about 11 electric and cable streetcar lines, eight failed and went into receivership.

By the end of 1893, 20 percent of the American work force was out of a job. Unemployment was probably higher in the Puget Sound region, so dependent on exporting natural resources to the East and across the seas. The lucky ones who remained employed got their wages sliced. Unable to make mortgage payments, the unemployed and many of the employed had to walk away from their real estate investments, even their own houses. King County foreclosed on hundreds of parcels, lots, and acreage owned by individuals, developers, and speculators when property taxes were not paid. Even some banks could not afford to pay property taxes. The few real estate transactions occurred at land values that had dropped by 40 to 80 percent.

The depression affected not only the poor but the middle class and the rich. Leigh S. J. Hunt, owner of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer since 1886, lost it. The Rainier Hotel, considered by some Seattle's best hotel, locked its doors. Another lavish hotel under construction when the Panic hit did not open its doors to its first guest for another 10 years. This was the Denny Hotel, located on the south slope of Denny Hill between 2nd and 3rd avenues just north of Virginia Street.

Kirk Loses Kirkland, Denny Loses His Shirt

On the east side of Lake Washington, Peter Kirk (1840-1916), who had started to build a major manufacturing center producing iron in a town he modestly called Kirkland, lost it all in the Panic. On Mercer Island in Lake Washington, C. C. Calkins, starting with an idea and a few hundred dollars, built a major resort with large landscaped grounds, Turkish Baths, and a steamboat to transport guests. He lost it within a few months after the Panic started.

The biggest loser was "Honest" David Denny (1832-1903). Denny had developed his Lake Union homestead plus property he purchased to the north into residential developments. He constructed electric trolley lines so homeowners could easily shop and work in downtown Seattle. In 1892 he purchased additional trolley lines to extend his developments even farther. At the south end of Lake Union he built Western Mill Company, the largest sawmill in King County. One estimate valued his holdings at $3 million. The Panic consumed it. David Denny and his wife Louisa Boren Denny (1827-1916) lived the remainder of their lives on a small farm at Licton Springs, located in the future north Seattle near North Seattle Community College.

The Panic of 1893 lasted for four hard years and then ended as quickly as it started when a ship of Klondike gold reached Seattle's docks in June 1897 and the county became, once again, "the boomingest place on earth."