On May 9, 1910, Friday Harbor residents are exhorted by renowned evangelist preacher Billy Sunday (1862-1935) to renounce the multiple evils of liquor and the saloons that supply it. Not coincidentally, the sermon comes one day before Friday Harbor, taking advantage of Washington's recently enacted "local-option" law, votes whether to continue to license liquor sales. Sunday's visit to Friday Harbor, the county seat of San Juan County in Northwest Washington, caps a campaign of several decades to eliminate the negative impact of the liquor trade on those who frequent the town's three saloons, their families, and even the character of the town itself. A county Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) group, among others, has spearheaded efforts to inform the community of the dangers and family tribulations caused by liquor and the progress of Prohibition activities around the nation. Billy Sunday, making a rare Monday appearance, gives a shortened, one-hour version of his famous "Booze Sermon" and delivers to an expectant audience a stunningly dramatic and persuasive diatribe against the liquor trade. The next day the town votes overwhelmingly to go "dry," and within months, the rest of San Juan County does too.

The Liquor Issue

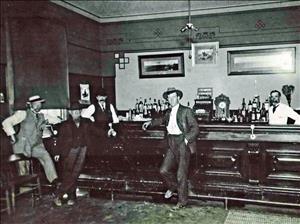

Friday Harbor became the county seat of San Juan County, an archipelago located between Seattle and Vancouver, Canada, in waters known today as the Salish Sea, when the county was formed in 1873 shortly after the 14-year boundary dispute between the United States and Great Britain over the islands was settled in favor of the U.S. However, few settlers populated the town until early in the 1890s, when one of its two general stores already had a well-patronized saloon operating in a back room. Shortly thereafter Jack Douglas (1859-1946) opened Saloon Best, which rapidly became very popular with thirsty islanders and very unpopular with those concerned about the insidious effects of the liquor trade on family life and the community. Soon a third saloon was opened, more, it was felt by many, than should be tolerated. A growing number of citizens began meeting to determine ways to combat the power of the liquor trade, joining a swell of efforts nationally to educate the public and persuade legislators to allow localities to decide whether or not to approve the sale of liquor in their jurisdictions.

Although there had been attempts at a temperance movement in the U.S. as early as the first quarter of the nineteenth century, it wasn't until after the Civil War that more concerted efforts were directed toward abolishing the liquor trade. The national Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was formed in 1874 when women had few legal rights: They could not vote and in some states they could not even own property nor have custody of their children after divorce. They were not allowed to participate in political meetings, which often took place in local saloons, and they had little political power. The WCTU provided a voice for those women and others who had experience and knowledge of all of the negative consequences of an uncontrolled liquor trade.

In 1893 the Anti-Saloon League was formed largely through affiliations between various Protestant evangelical denominations and the Methodists and Congregationalists. But temperance pressures at times were more individual than organizational. It was even reported to island newspaper readers in 1894 that "the young women of Whatcom are toying with vows of perpetual virginity by pledging themselves not to accept the matrimonial proposals of men who are not intelligent, honest, industrious, good-natured, cleanly in person and apparel, healthy, sober, church members and the total abstainers from liquor, tobacco, and profanity"("Northwest Brevities").

Both liquor sales and saloons -- largely unregulated purveyors of liquor to almost anyone coming through the doors -- were recognized very early on as serious problems in San Juan County and especially in Friday Harbor. In 1891 the inaugural issue of the first local newspaper, The Islander, included an editorial note that the liquor trade was so contentious a topic that the publisher felt it necessary to state at the very outset his views on the rights of all individuals and businesses in the community: "This paper will not condemn a merchant or farmer who visits a saloon for relaxation, nor will he set the dogs on a saloon or hotel keeper, because he knows that the business has been legitimatized and licensed by the United States Government, and therefore has a legal right to exist" ("Salutatory").He went on to say that the liquor traffic "is unquestionably an evil -- but it is licensed and paying the state a revenue devoted to educational purposes, and cannot therefore justly be criticized, and still less attacked" ("Salutatory").

The first meeting of the Friday Harbor chapter of the WCTU was called on October 4, 1898. According to the constitution of the organization, "the object of this Union shall be to educate public sentiment up to the standard of total abstinence, train the young, save the inebriated and secure the legal prohibition and complete banishment of the liquor traffic" ("Minutes ..."). By 1905 a county unit of 51 active and 11 honorary members had been organized with participants in Friday Harbor, on Lopez Island, and in Deer Harbor, East Sound, and West Sound on Orcas Island. Other groups formed as well. In 1904 the Friday Harbor Prohibition Alliance was organized and invited anyone interested in the cause of eliminating liquor traffic and saloons to attend the twice-monthly meetings; those who believed in God and Prohibition were eligible to become members. That same year at a privately held island Independence Day celebration under the auspices of the Prohibition Party Central Committee, a keynote speaker focused on the influence of the liquor trade on politics and urged that a third party was needed "that would make a stand for freedom from the saloon" (San Juan Islander [SJI], July 9, 1904, p.8).

The Campaign Strengthens

The year 1905 marked the first real progress in limiting the liquor trade in Friday Harbor. Although there had been a state law on the books requiring that saloons be closed on Sundays, enforcement at the local level was uneven at best. In April the board of county commissioners, responding to complaints that the law was not being observed at the three establishments in Friday Harbor, declared "it is the opinion of this board that such violations of the law shall be stopped forthwith," and that the saloons must close at midnight on Saturday and stay closed until 5:00 a.m. on Monday ("Saloons Must Close on Sunday"). In retaliation the saloon owners demanded that the law be equally enforced at all places of business and, acquiescing, the county prosecuting attorney gave notice to various merchants, including the proprietor of the barbershop, to comply with the law.

For a little while the ruling was "commendably observed," but by August it was reported that the situation had deteriorated and compliance seemed "to be more honored in the breach than in the observance" (SJI, August 19, 1905, p. 1). When the liquor license for the Tourist Hotel came up for renewal the following month, there was considerable pressure on the board of commissioners not to renew it. The local newspaper editorialized that "community sentiment here does not favor three saloons. In fact it is questionable if a majority of the people residing within the limits of Friday Harbor proper favor even one saloon, and yet there have been three here for years" ("As to ...").

While the board did not refuse to renew the hotel's license, it did raise the fee for all liquor licenses from $300 to $1,000 per year "in the hope of reducing the number of saloons in Friday Harbor and minimizing to some extent the evils which for a long time past had their origin in the liquor traffic here" (Liquor License Fee ..."). It was also hoped that the larger fee would encourage better compliance with the Sunday closure law and other regulations because the forfeiture of a license would be more expensive for the saloon owner. The following year renewal applications for the other two liquor licenses were approved, but a petition to reduce the fee for the licenses to $500 was denied after public outcry and a petition with signatures from San Juan, Orcas, and Lopez islands was presented to the commissioners.

Local Option

Meanwhile, a long statewide legislative struggle was continuing. For years, proponents and opponents had argued the merits of a local-option law that would enable individual communities to decide whether to allow the sale of liquor within their jurisdictions. The state Liquor Dealers Association backed legislators who would vote against the measure, while the Anti-Saloon League and other temperance groups supported those in favor. The arguments affected elections at all levels, with much coverage of candidates for all offices and their personal views on the issue. In San Juan County a candidate for prosecuting attorney came under particular scrutiny concerning the possibility that the liquor interests were backing him and therefore "will make it profitable for him to be their 'guide, philosopher and friend,'" (SJI, November 3, 1906, p. 4). It was thought he might be vulnerable to financial incentive since the salary for his office was only $400 per year.

The constant struggle to, at the very least, keep the saloons in compliance with existing law was an ongoing theme through the next years. Newspaper articles regularly noted that the closure laws were not being enforced; that Indians, who were forbidden to be served in the saloons, were frequent patrons; and that new county commissioners might possibly be in the pockets of the liquor industry. This seemed of special concern when, without notice to the public, the commissioners reduced the fee for liquor licenses from $1,000 to $700. When a saloon next sought renewal of its liquor license, the WCTU "respectfully" requested, once again, that the commissioners "refuse to enter into this unholy compact of making the people of our beautiful islands a partner in the saloon business, for a share of the profits in the form of a license" for a commerce that "retards growth, morally, intellectually and commercially," while it breeds crime, is the enemy of the home, brings lawless and disreputable men to town and in contact with children on the community's streets" ("W.C.T.U. Dept.," May 2, 1907 ...). The request was not granted. And all of this ongoing community contention was taking place against the backdrop of increasing national sentiment for Prohibition. By 1907 the annual report of the Associated Prohibition Press asserted that more than one third of the nation's population was then living under Prohibition or local-option laws.

Finally, in March 1909 a local-option law was passed by the Washington State Legislature. This law stated that any "unit" could petition for a special election to decide whether it would continue to license the sale of liquor. San Juan County was considered to have two units: the newly incorporated (1909) town of Friday Harbor and the remaining areas of the county. A special election could be called only once; thereafter the matter could be put on the ballot only at the general election. It didn't take long for the citizens of Friday Harbor to take advantage of the local option and call for a special election to be held in May 1910. The census enumerator reported the town population as slightly more than 400. When registration for the special election closed, the list had 152 names, but there was concern that "quite a number of men have been induced to register who have no interest here and ought not to be permitted to vote here" ("What Is the Population ...").

Campaigning on both sides intensified, but it was to the credit of the community that "on neither side [was] the contest one of boisterous effort, but it [was] nonetheless earnest" ("Friday Harbor Goes Dry"). Newspaper coverage of the campaign increased as did activities of the Anti-Saloon League and county WCTU and other local temperance groups on one side, and the liquor dealers on the other. Individuals did what they could to influence their fellow townsmen. (Washington women did not then have the right to vote; Washington's all-male electorate would approve a constitutional amendment granting women the vote at the November general election later that year). A moving letter from Charles McKay (1828-1918), one of the island's most revered pioneers, appeared in the Friday Harbor Journal (FHJ) recounting his personal experiences with the evil effects of liquor. He wrote of a son who had become an alcoholic and a nephew who had run a saloon and died of liquor, and he ended his letter with a plea: "O stop and think before you cast your vote and help to take temptation away from our weaker brothers and try to help them instead of putting temptation before them" ("Earnest ...").

Billy Sunday

William Ashley Sunday was a Midwest boy, born in 1862 and raised in Iowa. He had a difficult childhood including a stay in an orphanage beginning at age 9 when his mother could no longer care for all her children after his alcoholic stepfather abandoned the family. At 14 Billy returned home, where he received a high-school education and had his first tastes of athletics and oratory, at both of which he excelled. Baseball became his entrée to the world outside his small town when, at age 20, he was invited to try out for the Chicago White Stockings team in a game against the Boston Beaneaters on a day that winds blowing off Lake Michigan made the 32-degree temperature seem even colder.

Baseball was the great national pastime in the 1880s and 1890s, and Billy Sunday quickly became a recognized and popular player. While in Chicago, Sunday took advantage of the opportunity to further his education with some classes as a special student at Northwestern University, including a rhetoric course that helped him improve his speaking techniques. He also both took and taught classes at the Chicago YMCA. He gave talks on religion and "personal habits" to the young men, who were impressed that a prominent baseball player would take time to talk to them personally. "Eagerly, with serious purpose and a dose of theatrics, Billy was beginning the long struggle to make himself a public speaker" (Bruns, 48).

In 1891 he left baseball to take up work as the assistant secretary of the Chicago YMCA and to develop a religious ministry that was to become a national phenomenon. In 1896 he had his first experience as a speaker at a revival meeting, and his reputation as a preacher of singular talents was assured. Sunday wasn't just another minister railing from the lectern with upraised fist. "Part actor, gymnast, theologian, comedian, and stump orator, he could take an audience through a galaxy of emotions" (Bruns, 82). Although he preached on many topics, he saw the liquor trade as the worst evil facing the country and was eager to work with temperance leaders wherever he was visiting to focus on issues of local option and Prohibition.

By 1909 Sunday had largely developed the principal sermons that he would continue to use and refine throughout his career, including the famous talk often referred to as the "Booze Sermon," a long tirade featuring statistics, biblical references, moral and economic rationales, stories, and emotional exhortations. The overwhelming presentation "electrified, seared, and shocked audiences. Billy's virulence, stirring invective, zeal, and pathos were all there, packaged to great effect" (Bruns, 166).

So it was with great anticipation that a Friday Harbor Journal editorial in January 1910 announced that Billy Sunday was bringing his rousing messages to Western Washington that spring. "Billy Sunday will storm the citadel of the wicked in Bellingham in April. Fall in, ye sinners. Harden up your knees and soften up your hearts; and here's hoping the circulation liars fall penitently upon the necks of each other and resolve to be good before Billy Sunday quits the field" (FHJ, January 27, 1910, p. 4). Many islanders eagerly looked forward to Sunday's preaching in Bellingham, which was to take place over several weeks. So many wanted to travel to hear him speak that the owner of the steamship Yankee Doodle offered excursions to accommodate them at the special rate of $1 apiece.

Bellingham organizers had already suggested that Sunday plan to visit the islands, where the battle over saloons was in full swing. And when he learned that a local-option election was about to take place in Friday Harbor, and was invited to bring his message to the voters, Sunday broke his own rule about not preaching on a Monday (after a long, exhausting revival meeting the previous day), and announced that he would speak on San Juan Island the afternoon immediately before the option election. Temperance backers were elated, and plans were quickly put in place. The liquor dealers, too, had plans and arranged an outing by steamer to Waldron Island for their friends on election day.

The Sermon and the Vote

Billy Sunday and 45 associates arrived in Friday Harbor from Bellingham by steamer on Monday morning, May 9, 1910, and were fed lunch by the women of the Methodist Episcopal and Presbyterian churches before the presentation. The assembly took place in the Odd Fellows Hall, which was the largest venue in town for community gatherings. (The large building on the bluff above the harbor would, 70 years later, become the home of the Whale Museum.) Registered voters had been especially urged to attend, and seats were reserved for them at the front of the hall. The crowd overflowed the available space, and many outside the building on that warm day listened through the open windows to the program, which included the singing of patriotic songs and hymns. The pastor of the Methodist Episcopal Church had the privilege of introducing the visiting evangelist.

Sunday then spoke for about an hour, and "seemingly every second was so precious that he tried to put as many words into it as possible. Rapid-fire orator at all times, he threw on the high gear and opened the throttle ... and seemed determined to say more in fifty minutes that any man ever said in the same length of time before" ("Senator Cotterill and 'Billy' ..."). His speech was frequently interrupted by cheers, and it was generally agreed afterward by the mesmerized crowd that it was among the most masterful addresses ever experienced. "The avalanche of thought, coined into words, was like the leaping, bounding mountain rivulet, 100 times intensified," the editor of the Friday Harbor Journal lyrically declared (FHJ, May 12, 1910, p. 4). The audience was ecstatic, and many escorted Sunday down to the dock for his return voyage to Bellingham, singing and cheering enthusiastically along the way.

The powerful impact of Sunday's sermon clearly had its desired effect; voters the next day decisively chose to close the saloons of Friday Harbor and eliminate the sale of liquor. The vote was 36 for continued licensing and 87 against. All saloon licenses would expire at the end of the month, and by June 1 the saloons would have to be closed. The saloon owners asked the newly-formed town council for 90 days to close out their stocks of liquor, but the members denied the request, stating firmly that "this council has never issued a liquor license and never will" ("Saloons Must Close on First Day of June").

Undaunted, Jack Douglas of Saloon Best, a most enterprising businessman, packed up his stock of liquor and took it by boat to Brown Island, just across a narrow stretch of water from the town of Friday Harbor, where he set up operations under a tent, confident that determined drinkers would be willing to make the trip. Three men drowned during the following months trying to get there or back. Other stocks of confiscated liquor were temporarily locked in the small town jail, but the barrels were soon found to have been siphoned off by someone who creatively drilled a hole in the wooden wall of the jail and then into the barrels.

As word of the election spread, letters arrived from former residents and well-wishers praising the outcome. And interest in the power of the local option continued. County activists, newspaper articles, and temperance supporters moved on to advocate that the county have a similar election in the fall, and in October official notice appeared in the newspapers that on the general-election ballot would be a question concerning the sale of liquor in the county outside of incorporated Friday Harbor. The experience of the town since the election was touted as persuasive evidence against licensing liquor sales. It was reported that businessmen felt that local commerce had improved, men seen around town were better dressed, and women could move about without fear of unpleasant encounters with the inebriated. The shouting and singing that had disrupted the community late into the night had ceased, and "all is peace now" ("How Local Option ...").

In November 1910, county voters came out strongly opposed to the sale of liquor; the tally was 141 for continued licensing and 375 against. Legal sale of liquor ceased in San Juan County by 1911. The temperance campaign widened and intensified; the state of Washington would approve Prohibition in 1914 (effective as of 1916), and the country as a whole in 1919. It was the beginning of a great social experiment.