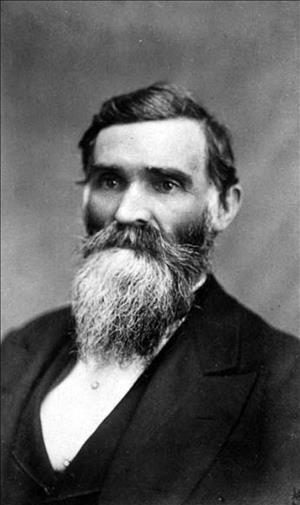

"A Pioneer of Three States -- Adventurer, Prospector, Miner, Trader, Explorer, Promoter, Soldier and Public Official," was how Edward Warbass was once described ("San Juan's Best Known Pioneer"). He came west for the California gold rush, migrated to Oregon Territory, served in the 1855 Indian Wars, and worked as a sutler for the army at Fort Bellingham and then on San Juan Island, situated between Seattle and Vancouver, Canada, in the Salish Sea. His adventures were rich and varied. He claimed homestead land, initiated an oyster-farming project, moved a herd of cattle across several states, prospected in Montana and on Orcas Island, and traveled the Northwest. But it was San Juan Island that he always considered home. He served in the territorial legislature, as county auditor, and as deputy customs officer at Roche Harbor on the north end of the island. Warbass was instrumental in the creation of San Juan County and promoted Friday Harbor as the county seat. His home and wharf just south of town were busy centers of community, commercial, and official activities. Warbass is indisputably among San Juan Island's most revered pioneers.

Adventurer, Entrepreneur, Explorer

One of 11 children of John and Margaret Warbass, Edward was born in Hamburg, Sussex County, New Jersey, on February 1, 1825. He spent his growing years in New Jersey but as a young man moved to New York City where he entered the mercantile business. When news of the California gold discovery reached New York City in 1848, Warbass enthusiastically prepared for adventure. He collected a large assortment of goods and booked to leave on the first ship for the West Coast, but it was too overloaded to take on his extensive baggage, and he had to wait three months for the bark Victory and the six-month-long voyage around Cape Horn. The ship was crippled in a terrifying storm and barely made it to San Francisco; his carefully selected goods were ruined. Nevertheless, by 1849 he was in the auctioneering and commission business in Sacramento. The climate there, however, was not good for his health, and he soon left for Astoria at the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon.

Drawing on his early business experience, Warbass promoted himself as a dealer in produce and merchandise and opened a store in Astoria. He explored farther inland north of the Columbia in what would soon become Washington Territory, heading up the Cowlitz River, an important segment of the vital transportation corridor between the Columbia River and Puget Sound. He established a second store at Cowlitz Landing near the head of the river and, with a partner, another at Monticello (now Longview, Cowlitz County). At Cowlitz Landing (near present-day Toledo) he ambitiously began to turn a primitive wharf and staging area into a town with a hotel and other enterprises to prepare those arriving by canoe for the second, overland part of the journey north to the Sound or travelers from the north for the Indian-guided canoe trip to the Columbia. "In a moment of infelicitous self-promotion" (Ficken, 7), he renamed the town Warbassport.

Here, north of the Columbia, English settlers outnumbered Americans 10 to 1, and the British Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) had large farming and trading centers throughout the area. It was Warbass's first experience with the HBC but certainly not his last. By 1851, at age 26, he had been appointed the first U.S. postmaster north of the Columbia; among his duties was a monthly trip to take the mail from the garrison at Fort Steilacoom to Portland. Through a customer in his store he heard of coal discoveries near the Cowlitz River and, with one of his brothers who had also come west, helped establish a San Francisco-based company to develop the newly found resource. By 1852 a sawmill and gristmill had been added to the increasingly busy Warbassport community.

Warbass's stores, where he served French Canadian traders and Klickitat Indians as well as settlers and travelers, were probably like many others on the frontier. Customers had little cash, so payment was often in beaver skins or other furs or goods such as butter, cheese, or potatoes. Items for sale included flour, lard, sugar from Hawaii, tea, coffee, beans, tobacco, dried fruits, and other goods. But life for Warbass was never all about work, and he relished every chance to explore the area, traveling by canoe to Snoqualmie Falls, camping on Elliott Bay before any settlement there, and prospecting for gold only 25 miles from the Canadian border near Kettle Falls and Lake Pend Oreille above Fort Colville, a round trip from Warbassport that he made on foot. In 1851 the Columbia Territory Commission met in the Warbassport store, and the 24 delegates resolved that, for "reasons too well-known to require repetition" (Ficken, 44), Congress should separate the lands north of the Columbia River from Oregon. On March 2, 1853, Congress approved the creation of Washington Territory.

In 1855 Warbass took on a new responsibility when Isaac Stevens (1818-1862), first governor of the new territory, commissioned him as captain of a company of pioneer volunteers assigned to guard the important Cowlitz Pass and build and operate ferries on the Cowlitz River during the Indian uprisings in the area. He furnished horses and supplies costing him $1,600 for which he was never reimbursed, served for four months, and received a total pay of $70. Not until 45 years later did Warbass learn he was eligible for a newly authorized pension for Indian War veterans.

Storekeeper for the Army

Ready for a change, Warbass moved north to Whatcom County. He had been appointed by the U.S. Secretary of War to the position of post sutler (or storekeeper) for Fort Bellingham, which had been established under Captain George Pickett (1825-1875) in 1856. Discipline there apparently was lax, and on several occasions Warbass was dismayed to discover that soldiers had broken into the store and stolen clothing and other items. After just three years the fort was closed and the troops, still commanded by Pickett, moved to San Juan Island to protect American interests there while competing British and American claims to the San Juan archipelago were in dispute.

On July 27, 1859, Pickett's infantry company landed near the south end of the island at a wharf owned by the Hudson's Bay Company, which had long had interests on the island including farming and sheep-herding operations (it was an American settler's shooting of an HBC pig that famously touched off the boundary dispute). Within a few days Warbass, who had accompanied the troops, was building a log cabin to serve as the company store near San Juan Town, a ramshackle settlement composed primarily of saloons and brothels on the shore of a shallow harbor near the southeast tip of San Juan Island. Throughout the years of U.S. and British military occupation only the post store was allowed to sell goods to island settlers and Indians as well as soldiers. Resisting involvement in the lawlessness of the town and the island's on-going political, military, and residential disputes and conflicts, Warbass was viewed during his tenure there as "of untarnished reputation" (Bailey-Cummings, 70).

Island Settler

By 1860 Warbass had bought a farm near San Juan Town, but civil law during the military occupation was minimal, and normal procedures for registering property were largely suspended, so many settlers wanting to homestead resorted to establishing a squatter's claim. Unfortunately, Warbass was not the only one who claimed some of this particular land. The area had been part of the HBC property, and was claimed by the company agent. In addition Stephen Boyce (1829-1909), another pioneer settler, claimed it as a farm, and Isaac Higgins, the postmaster in San Juan Town, claimed it as a town site. In 1863 Higgins demanded that Warbass relinquish possession of his property except for the lot with the farmhouse on it, for which Higgins wanted $25 rent. When Warbass refused, Higgins tried to have the land-title dispute settled in court, but the justice of the peace was dismissed by the American military commander, and the matter was never brought to trial.

Meanwhile Warbass contributed to the community in a number of unusual ways. In 1859 he imported the first California mountain quail to the island. They flourished and had populated the island extensively by the 1880s. And creative problem solving was certainly one of his talents. Prior to 1860 there had been a number of small but prized oyster beds in a shallow lagoon near the American military encampment, but the winter of 1860-1861 was bitterly cold, freezing the lagoon solid and killing the oysters. The next summer Warbass sent a party of Indians to the Samish Flats in Skagit County to gather seed oysters, which were brought back and planted in a larger and deeper lagoon in Griffin Bay. The undertaking was so successful that many decades later local Indians were still able to gather large harvests that they sold to island canneries for processing.

Warbass decided that he wanted to stock his homestead with sheep, and in 1864 he traveled to Oregon, where he planned to purchase his flock. Once there, however, he found himself unable to obtain the sheep he wanted. Undaunted, he instead bought a herd of cattle that he drove north, wintering them in the Yakima Valley, and then, in the spring, taking them on to Montana where he eventually sold them. Lingering in Montana, he visited some of the many mining camps in the area. Thinking that here were discoveries, and perhaps fortunes, to be made, he abandoned plans for an immediate return to San Juan Island and joined the prospectors, working in mines across the Northwest. It was eight years before he finally returned, just in time to participate in the dramatic changes taking place in the governance of his island community.

Public Servant

As early as the 1850s Edward Warbass had taken on public service while living in the Cowlitz River area, when he had been appointed the first auditor of Lewis County, then part of Oregon Territory. In 1860, shortly after moving to San Juan Island, Warbass had been elected to the Washington territorial legislature as a representative from Whatcom County (to which the disputed San Juan Islands were assigned by the legislature).

With the resolution of the international boundary dispute in 1872 in favor of the U.S., the islands were once again included within Whatcom County and, with little appreciation for the independent character of its new citizens, Whatcom "welcomed the San Juans to its bosom by slapping an 8-mill-on-the-dollar tax on the islanders' personal property" (Richardson, 176). Islanders were irate.

Warbass, just back from his travels, came up with a plan. "Almost before Whatcom's politicos knew what was happening" (Richardson, 177), he organized a petition asking that the legislature separate the San Juan Islands from Whatcom County. Although many secondary sources over the years have stated that Warbass was a legislator when he led the effort to create San Juan County, he was not then a member of the territorial legislature (he served only in the 1861 and 1877 legislative sessions) and it was Whatcom County Representative Edward Eldridge who quickly shepherded the proposal through the legislature. On October 31, 1873, less than a month after the beginning of the first legislative session since the boundary decision, San Juan became Washington Territory's smallest county. And, not surprisingly, the first board of county commissioners immediately appointed Warbass to public office -- as auditor of the new county.

But where was the new county government to be housed? Raucous San Juan Town hardly seemed to Warbass like the proper atmosphere for a county seat, and it was not well situated for shipping and commerce. North of San Juan Town small settlements were being established on the east side of the island at Argyle and around the blacksmith shop at Madden's Corner, but Warbass preferred a site even farther north. The new town Warbass envisioned should, he thought, be on the wooded, east-facing shoreline along a deep harbor that had long been known as Friday's Bay, named for a Kanaka (Hawaiian) HBC sheepherder who had tended his flocks on the prairie sloping up from the water there.

With his legislator's knowledge of a little-used provision in the homesteading laws, Warbass applied for 160 acres of government land, not for his personal use but to be developed as a county seat. Settlers, he reasoned, would find the site attractive and purchase town lots, thus providing funding for the county government. And he was sure that the deepwater harbor would become a busy port of call for commercial and other boats of all kinds. He built a 16-by-24-foot log shack to serve as the county courthouse as well as his auditor's office and his residence, and waited for newcomers to populate the town. And he continued to wait -- for three solitary years. The saloons of old San Juan Town were too much of a draw for settlers in the area who could, furthermore, establish homesteads around the island for free rather than pay for town lots. Warbass convinced the government to create a post office in his one-person town, but the mail boat never stopped because there was no mail addressed to Friday Harbor. In frustration Warbass took to addressing an envelope to himself and riding his horse to San Juan Town to post it, so that the boat might be enticed to deliver it to Friday Harbor.

By 1876 Warbass was still the only resident in town, and voters replaced him as auditor with Orcas Island resident John Bowman, "a slick dealer unhampered by superfluous scruples" (Crawford, 46). Bowman teamed up with similarly-minded Orcas storeowner Joe Sweeney (1841-1920), and together they hatched a scheme to purchase a large share of the prime town lots at a discount and then sell them off, making a tidy personal profit for themselves. Warbass was beside himself with rage at this underhanded plan, the personal profiteering, and the cheap sale of property that he had envisioned would be of high value to the community in years to come. He bitterly swore that he would never live in the town again.

Furious and resolute, he established a homestead immediately contiguous to the town boundary. He had Captain Pickett's former residence from American Camp (the first home built on San Juan Island of sawed lumber) dismantled, moved, and rebuilt on his property just south of town overlooking the harbor. He named his home Idlewild, and it would be the much-cherished residence to which he always returned for the rest of his life. While Pickett had been on the island, he had lived with an Indian woman with whom he had a son who became a talented artist. Over the mantle of the fireplace at Idlewild was hung a large portrait of George Pickett painted by his artist son. Through the following years Warbass developed his property, cultivating orchards and fields, raising sheep and other livestock, building a wharf and boathouse and water storage tanks, adding cottages for visitors, and drilling a well to enable fresh water to be piped to the shoreline. There were always new projects to undertake.

After leaving his position as auditor, Warbass, now in his 50s, returned to the territorial legislature, serving one term representing San Juan and Clallam counties. Despite his continuing ire with Bowman and Sweeney, he was truly committed to having Friday Harbor become a thriving community, and as a legislator he was able to have a United States customs officer assigned to the town, thus increasing the population to a total of three. It would be almost 10 years before a second store, with a saloon in the back, was built and settlers began to purchase town lots at greatly reduced prices and to build what was to become the most important concentration of governmental, commercial, and private properties in the islands.

Throughout the next decades, Warbass continued to serve the island in various capacities. He was appointed justice of the peace and often addressed with the honorific "Judge." He served as deputy collector of customs at Roche Harbor in the 1890s, and he became increasingly involved in party politics. In 1894 Warbass was the representative of San Juan Precinct 3 at a "citizen's convention" that sought to overturn the influence of the prevailing Republican Party leaders. Included in the resolution unanimously adopted by the convention were complaints that "the politics of San Juan County has hitherto been controlled by a certain ring or combination of persons whose sole aim has been to further their own interests," and that "the present Republican Ticket is made up of persons who secured their nomination at the instigation of the Bosses of this county who ignored the will of the people" ("Citizen's Convention"). The resolution demanded "an administration (chosen by the people) pledged to an economical and careful administration of the affairs of the county," and that "business capacity and honesty be the sole qualifications for office" ("Citizen's Convention"). That same year Judge Warbass was chosen as chairman of the local Democratic convention and to represent San Juan County at the state convention in North Yakima.

Private Citizen

The final years of the nineteenth century were busy ones for Warbass. He continued his work as deputy customs collector at Roche Harbor -- even, on occasion, being entertained by the formidable John S. McMillin (1855-1936) of the Roche Harbor Lime & Cement Company, the powerful leader of the county Republicans -- but made frequent trips to Friday Harbor to visit friends and to ensure that Idlewild was properly maintained. In 1896 he found himself listed in the paper as a tax delinquent, owing the county the then-large sum of $18.85 on farm property that he had largely abandoned, but, nonetheless, just the next year he applied to purchase some tidelands near Idlewild.

Meanwhile, his health was becoming an increasing problem. He had struggled with asthma most of his life, and he began to consider whether a change of climate during the long, cold island winters would be beneficial. Therefore, in December 1897 Warbass left for a planned winter-long stay in California. Unfortunately, conditions were not as he had hoped, and he returned early, declaring that because California was so very dry and dusty, the climate there was even worse for his asthma and, consequently, "he came home as the surest method of relief" (Islander, February 10, 1898, p. 3). He was sufficiently ill that he was taken in by friends and, with their care, he slowly began to improve. By July 1898 he was feeling well enough to visit Lopez Island with a friend to explore some prehistoric fortifications that had been found there. And that same year, at age 73, he finally gave up his work at Roche Harbor and returned home. He had rented out Idlewild during his absence, but now he was able to begin repairs and restoration of the house and boathouse. But Warbass could always be enticed away from work for some new exploration, and 1902 found him and two companions on Vancouver Island prospecting in the Mt. Sicker mining area and enjoying some sightseeing in Victoria.

As he settled back into life at Friday Harbor, Warbass took up the mantle of a long-time community leader and was treated as an honored elder. Numerous visitors were welcomed to Idlewild. In August 1899, San Juan County Teachers Institute participants brought a picnic lunch to the "historic house" ("The County Institute"), and Warbass was a genial host as they sat on the lawn under the trees, listening to his reminiscences. Later that year, Warbass considered the proposals of men from Whatcom who wanted to plant oyster beds and lobsters in the small bay at the foot of his property. Not that Idlewild was always an idyllic place to be. In 1901 a local newspaper noted that "Judge Warbass has for years been greatly annoyed and the value of his home, naturally a most delightful spot, as a summer residence has been greatly impaired by the stench arising from the fish offal dumped into the water at the cannery" ("The Nuisance Question").

Warbass's wharf was in constant use for offloading shipments of all kinds including coal for the government offices. But, a few years into the new century, a local newspaper reported that extensive work on the wharf was being completed "in readiness to turn [it] over to the government for use as a revenue launch station" where a ship, previously assigned to Fairhaven, near Bellingham, would be stationed. Warbass slowly began to reduce his responsibilities and possessions, placing ads in the newspaper for sales of livestock and notifying the public that he had cottages for rent. In 1904 the cottage occupants were women students attending the University of Washington summer-school biology program (male students were housed in tents nearby). He also sold most of the trees on the property for lumber and cordwood; a crew of eight workmen began clearing what had been heavily wooded acreage. Nevertheless, there were always improvements to be made and, at the age of 80 in 1905, Warbass had a new, covered, 4,000-gallon water reservoir built up the slope from his home.

In addition to his properties on San Juan Island, Warbass also owned a mining claim on Orcas Island, 800 feet above sea level. Not much work had been undertaken there, but in 1901 the mine shaft needed to be bailed out, and in 1904 he had a road cleared from President Channel up to his claim in hopes that it could finally be properly developed. Ever struggling with his asthma, Warbass said that he felt better when he was a few feet above sea level. He had lumber shipped from Idlewild to Orcas Island, and two San Juan Islanders went over to build him a small "cozy cottage" where he planned to spend his summers.

But Warbass's health continued to deteriorate, and in March 1905 he was confined to bed for more than two weeks, suffering a severe attack of influenza, or "grip" as it was called at the time, which in turn increased his struggles with asthma. He slowly recovered but recognized that he no longer had the energy to maintain his large property. In 1906 he sold Idlewild to Andrew Newhall (d. 1915), a well-regarded steamboat owner, mail contractor, and mill owner. Newhall's purchase included more than 100 acres immediately adjoining Friday Harbor and a mile of waterfront including the wharf, springs, tanks, and buildings of the United States revenue-launch station. Warbass retained only "a point of land comprising about an acre on the peninsula across the bay from his historic and picturesque home ..." ("Capt. E. D. Warbass ..."). In September he felt well enough to go with a friend to the Harrison Hot Springs in British Columbia for a visit lasting a few weeks. But later that fall, while on a trip to Port Townsend, he again fell ill and had to be admitted to the Northwestern Sanitarium there. He was eventually able to return to San Juan Island, but he never really recovered, and, near midnight on Christmas Eve, 1906, Edward Warbass died.

Not long before his passing, a local writer had noted "it may well be questioned if there is any living pioneer of the Pacific coast who has had more varied experiences than Capt. Warbass, or who has been more closely identified with events which are part of the history of the great Northwest" ("San Juan's Best Known Pioneer"). Although he had never married or had children of his own, Warbass was mourned as truly a founding father of the San Juan Islands. The pallbearers at his funeral -- Stephen Boyce, Charles McKay (1828-1918), C. Rosler (1834-?), E. P. Bailer (1836-?), John L. Blair (1835-1932), and Andrew Newhall -- constituted a remarkable gathering of early pioneers responsible for the development of the island from the first struggling days of settlement to the then-thriving island economy and busy Friday Harbor community that Warbass had envisioned more than 30 years earlier. Islanders came out in great numbers to honor him at his funeral and interment in the quiet cemetery overlooking the beautiful San Juan Valley. The "fine granite monument" (San Juan Islander, April 20, 1907) placed there by his niece to mark his grave may still be seen today.