On the weekend of June 16-17, 1934, a 60-year old sailing ship opens as a museum on the Seattle waterfront. Berthed immediately northeast of the Ballard Locks on the Lake Washington Ship Canal, the St. Paul is Seattle's newest tourist attraction -- a combination nautical museum and saltwater aquarium. This ambitious goal, if successful, will fulfill long-held dreams of city boosters. Unfortunately, times are not favorable, and the enterprise folds after only a few years.

Last of the Down Easters

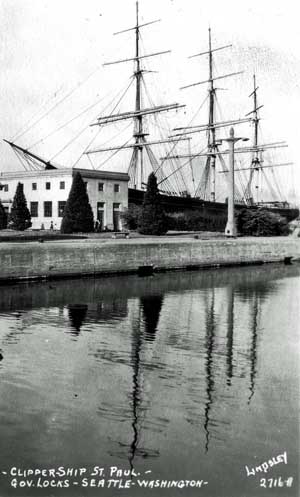

"Visit the Colorful Old Ship St. Paul Aquarium & Museum, For 10 Cents." Thus read a sign affixed to the mainmast of the sailing ship berthed at the Government Locks during the 1930s. How she came to be there is a long story that we will condense to a few essentials.

The St. Paul was called by many names. She was an American clipper ship -- a fast-sailing three-masted ship used in the cargo trade. She was built in Bath, Maine, in 1874, making her a Down Easter. Multiple voyages around the fearsome tip of South America entitled her to be called a Cape Horner. She was square-rigged (primary sails perpendicular to the keel), full-rigged (three or more square sails), and often called a windjammer, although her hull was wooden, not steel. And, of course, she was a "hell ship" during much of her early career, a badge of dubious honor conjuring up images of scurvy, press gangs, floggings, and worse.

Maritime historian Michael J. Mjelde devotes a five-part article in the quarterly journal The Sea Chest (September 2011 through September 2012) to the "remarkable career" of the St. Paul, including her three decades hauling grain, lumber, cotton, molasses, kerosene, and other cargo to and from Britain, the United States (both coasts), and the Far East (Mjelde, "St. Paul -- Part V," p. 27). As the age of sail drew to a close, the St. Paul, like her sister ships, found herself on the job market. A stint as a cannery transport to and from Alaska brought her to Seattle waters; when that job ended in 1924 she was put out to pasture in Lake Union alongside other forgotten sailing ships and World War I hulks.

By 1930 the St. Paul was towed to the bone-yard at Houghton on Lake Washington (today's Carillon Point in Kirkland) for a date with the wrecker's blow torch; while on death row she became a curiosity for tourists, perhaps inspiring one man to consider the possibility of extending her life.

Three Men and a Tub

The St. Paul owed her reprieve to three men, each with far-reaching stories of his own. C. Arthur Foss (1885-1964), scion of the Foss tugboat family, took an interest in the old clipper and purchased her from her last owner, the Pacific Coast Company, in 1930, as a personal investment. Foss had a deep love for maritime history and envisioned the ship as a museum. Along with his brothers, Arthur Foss ran the Foss Launch and Tugboat Company established by his parents Andrew and Thea Foss. (About the time he was working to establish the St. Paul as a museum, his namesake, the tug Arthur Foss, was starring in the 1933 movie Tugboat Annie.)

Foss was involved with a group of science and nature enthusiasts loosely organized as the Puget Sound Academy of Science; in the same year he made the purchase, Foss offered to lend the St. Paul to the Academy for use as a floating museum, and on the evening of February 26, despite heavy winds, she was towed into place just east of the Ballard Locks buildings

The Academy -- not a school, but an affinity group -- was the brainchild of Henry Landes (1868-1936), geologist, one-time interim president of the University of Washington, and Dean of the College of Science at the University. Landes is perhaps better remembered today as the husband of Bertha Knight Landes (1868-1943), Seattle's first woman mayor.

Founded in 1928, the Academy offered its members lectures, field trips, and films on topics such "our little sister republics to the south" ("Tacoma Lectures") and "Spring at 7,000 Feet" (Northwest Naturalist, June 1934). With the offer of the use of the St. Paul, equipping the marine museum became the Academy's primary focus. The group's newsletter reported regularly on the needs of the museum. In an article announcing the official opening, The Northwest Naturalist reported on progress:

"By the 16th the ship will have been put in a safe condition, with a good gangway completed, and the hatches and stairways safely guarded. There will be four large tanks of fishes, a reconstructed tide pool alive with crabs, shellfish, and other beach dwellers, a bit of swamp with cattails and frogs, and various small tanks of tiny tropical fish, and marine and fresh water life" ("Marine Museum to Open").

Landes and Foss tapped a young naturalist, Floyd W. Schmoe (1895-2001), to direct the Academy and the museum ship. His stint at the Academy was only a small part in Schmoe's long and wide-ranging career as an educator, writer, pacifist, and social-justice activist. Following his association with the University of Washington and the Academy of Science, Schmoe, a Quaker, worked closely with the American Friends Service Committee helping Japanese Americans affected by the federal exclusion orders of 1942. After World War II ended, he traveled to Japan to build houses for those left homeless by the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In his nineties Schmoe actively helped build peace parks in Seattle's University District and in Seattle's sister city, Tashkent. Like Landes, Schmoe had a famous relative; one of his daughters married Japanese American activist Gordon Hirabayashi (1918-2012).

Schmoe was a jack-of-all-trades when it came to his duties at the Academy. In the June 1935 issue of The Northwest Naturalist, in which he foreshadowed the demise of the Academy and the newsletter, he wrote:

"The editor, in addition to his regular work, was also business manager, chief correspondent, proof-reader, mailing clerk and printer's devil, so we take all the blame for the numerous mistakes which have appeared. Please forgive us" ("Editor's Note").

Strange Cargo

The Salt Water Aquarium and Marine Museum officially opened to the public the weekend of June 16 and 17, 1934. The Ballard News reported that "scores went aboard the old ship for the first time to see the tanks of marine life placed on exhibition there" ("Scores at Opening").

According to a promotional booklet prepared by Schmoe, the plan was to use the two 'tween decks, between the top deck and the hold, for displays:

"On the upper 'tween deck is told, by means of exhibits of primitive and historical boats and boat models, pictures, etc., the story of man's development of his ship, into which exhibit the St. Paul itself fits nicely. On the second 'tween deck the salt-water aquarium is located in which are exhibited living fishes and other marine life from the waters and shores of Puget Sound" (Marine Museum and Aquarium, 4).

In terms of living exhibits, the aquarium level of the museum boasted four tanks of fish in 1934, among them Alaska stickleback, pipe fish, yellow-banded perch, blennies, and cultus cod. "Four-foot sharks, twenty-rayed starfish, big sea anemone, and even octopus have been displayed at times but the amount of sea water available with present equipment is too limited to keep the larger forms for now" ("Aquarium News").

As for the historical exhibits, we find in the newsletter and newspaper articles tantalizing hints of what the museum had to offer or expected to acquire -- relics of the ship Lady Janesborough, a ship's medicine handbook from before the turn of the century, a mahogany outrigger canoe from the island of Jolo in the Philippines, a model of a Chinese junk, C. Arthur Foss's personal collection of bits and pieces of wrecked sailing ships, and a pair of vestigial whale "legs." A newspaper report prior to the museum opening promised that "The St. Paul will be decorated in the style of the '80's' and its decks will be adorned with figureheads from old sailing ships, ship equipment of historical interest, Indian canoes and other articles of a marine museum type" ("Floating Museum Now in Place").

The reality may have been much different. In the Academy newsletter, Schmoe writes optimistically about the future of the museum: "It will be interesting to watch the strange cargo of the St. Paul grow -- and more interesting to have a hand in making it grow" ("Marine Museum to Open"). However, in the next paragraph -- as in future issues -- he appeals to his readers for help in "making it grow:"

"If any members of the Academy know of objects of marine interest such as log books, pictures, navigating instruments, small boats, ships bells, wheels, whaling gear, etc., the director of the Marine Museum would be very happy to have information of them" ("Marine Museum to Open").

It is unclear how much of the vision of a maritime museum was realized during the few years it was open. It is also doubtful that the little aquarium ever grew much beyond the original four tanks. There are hints in the newsletters of difficulties keeping stock alive. Four years following the opening of the St. Paul aquarium, Ivar Haglund (1905-85) launched a more memorable aquarium on Seattle's waterfront.

The Ship as Museum

Whatever the shortcomings of the historical and aquarium exhibits, there was no doubting the attraction of the ship itself. At 228 feet long and with a mainmast at least 150 feet tall, the ship towered over the other ships and structures at the locks.

Michael Mjelde recounts visits to the St. Paul by several lads, who all described the thrill of finding themselves on board a real sailing vessel such as they had read of in adventure stories. One of these lads, Gordon Jones, later wrote a full account of his 1934 visit when he was 15 years old:

"The St. Paul's masts loomed high above the maintenance buildings on the north side of the canal. Some hastily erected steps with one landing twisted up the vessel's starboard side. A small sign announced the entrance charge of ten cents. No one was visible. And it was quiet -- as if the old ship were in a deep slumber. There was a container at the top of the stairs, into which I dropped an all-silver dime. I stepped upon the deck -- into history.

"There was not a thing aboard the vessel which did not amaze me. I was impressed by her size, her loftiness, the height of her bulwarks, the little headroom under the fo'c's'le head where the windlass was situated. Some of her lower rigging lanyards were recently replaced but not yet taken up tight. It appeared to be a useless effort, for there were many signs about of a hard used object, a neglected creature still afloat only because of the work put into her originally by conscientious craftsmen and mariners long gone with whom she no doubt felt an affinity" (Jones, 39-40).

Jones's description of decay is echoed by the other visitors quoted in Mjelde's subsequent article; the St. Paul was not in good shape. Clearly the Academy had not reckoned fully with the costs of maintaining a huge wooden ship.

Voyage End

It is unclear how long a museum and/or aquarium operated aboard the St. Paul. Newspaper accounts indicate the museum ship had at least two somewhat successful "seasons," presumably in the summer months of 1934 and 1935. In October 1935, Floyd Schmoe told The Seattle Times that the museum had been visited by "Twenty thousand persons from every state and from several foreign countries," and claimed that number was double that of 1934 ("20,000 Visitors").

On Halloween in 1936, Schmoe held an open house on board the ship with guided tours of the exhibits. About this time the Puget Sound Academy of Science disappears from the historian's radar; the death of Dean Landes in 1936 meant the loss of its principal founder and booster.

Nonetheless, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers photographs dated 1940 and 1942 in possession of Friends of the Ballard Locks show the ship with museum signs still on display, an entrance arch of whale ribs, and gangplank deployed. A June 6, 1941, article in The Seattle Times describes the ship as a "marine museum," but does not mention any exhibits either of fish or artifacts ("Windjammer May Sail Again"). Instead, the caretaker, W. G. Bille, is quoted as saying that he and his wife operate a restaurant on board the ship, catering largely to locks employees. It is likely that, while the ship was still open to visitors, most exhibits of nautical artifacts and tanks of fish had been removed by this time. The same article suggests that the old clipper might be returned to use as a cargo ship, due to the scarcity of vessels caused by World War II. While the war certainly brought a great demand for shipping, by that time the St. Paul was probably too far gone to be of use.

In the spring of 1942, the St. Paul was sold by Arthur Foss and towed out of the Ship Canal and up to Vancouver Island. There she was given one last job -- to serve as part of a breakwater at Oyster Bay, one of three breakwaters along the east coast of the island made up of old ships. A few relics of the ship were salvaged and made their way into the collections of the Puget Sound Maritime Historical Society, the San Francisco Maritime Museum, and Mystic Seaport in Connecticut.

The St. Paul museum ship wrecked on the shoals of the Great Depression, World War II, and poor planning. Three years later in 1945, an item in the Pacific Marine Review read:

"Leaders in Seattle shipping circles are urging that a marine museum be established in a downtown building or on the Seattle waterfront where ship models, ship pictures and equipment from famous ships that sailed the Puget Sound and Pacific Ocean trade routes years ago would be on display. Such an institution was formed several years ago and was set up aboard the old sailing ship St. Paul, and was maintained by the Puget Sound Academy of Science" ("Seattle Marine Museum").

The statement above, barring the last sentence, could have been written at many points during Seattle's history. Despite a number of attempts, in 2016 the dream of a dedicated maritime museum still eludes the city.