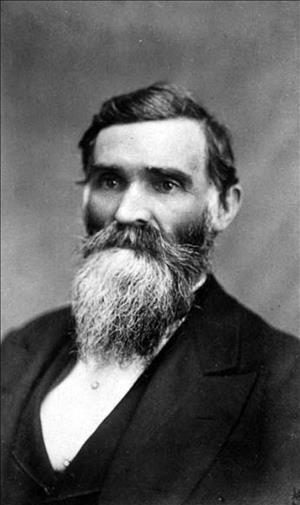

On July 27, 1859, U.S. Army sutler Edward Warbass (1825-1906) accompanies Captain George Pickett (1825-1875) and 45 soldiers from Fort Bellingham when they disembark at the wharf at San Juan Town on San Juan Island, the most westerly island of an archipelago lying between Vancouver Island, British Columbia, and Washington Territory on the United States mainland. At age 34, Warbass already has had a career of adventure, commerce, and exploration, but henceforth San Juan Island will be his home. His introduction to the island occurs amid tensions between Great Britain and the U.S., each of which claims the island since the boundary through the waters off the coast between the two nations' territories is not clearly defined in the Oregon Treaty of 1846. Warbass will be among those caught up in the military and political disputes of the day, but his integrity, accomplishments, and character will be acknowledged by participants on both sides of the conflict as above reproach, and he will go on to decades of public service and private achievements on his beloved island, including spearheading creation of San Juan County and founding Friday Harbor as the county seat.

Edward Warbass, an adventure-seeking young man with training as a storekeeper, left the East Coast for California shortly after news of the discovery of gold had reached New York. He worked briefly in Sacramento in 1849 and then moved north to the Columbia River area, first to Astoria, and then on up the Cowlitz River to Cowlitz Landing, the site of transition from river to overland transport between the Columbia and Puget Sound. He established a store at Cowlitz Landing (which he renamed Warbassport) and soon developed a thriving village serving settlers, fur traders, Indians, and military personnel as well as travelers in need of supplies and transportation (canoes and Indian guides for the river passage, and horses for the overland trip).

Hudson's Bay Company and British Settlement

The settlers in the Cowlitz River area at the time were primarily British, and the largest enterprise was the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) which, since 1821, had been developing an extensive network of fur-trading posts and agricultural operations throughout the Oregon country (as the Pacific Northwest was commonly known at the time) with an administrative headquarters at Fort Vancouver (site of today's Vancouver, Washington). Because of this widespread presence and the fact that only a small number of Americans were coming north of the Columbia River to homestead, the British government felt that it had a superior claim to the area north of the river despite the agreement at the Anglo-American Convention of 1818 for joint occupancy of the Oregon country and the establishment of a firm boundary between U.S. and British territories on the 49th parallel of latitude from Ontario to the Rockies.

But the British relinquished those claims in 1846, when the Oregon Treaty further extended the 49th parallel boundary through the Pacific Northwest, giving the U.S. possession of all lands south of that latitude to the "middle of the channel which separates the continent from Vancouver's Island and British territory" ("The Oregon Treaty ...," 181). Within little more than a decade, that vague descriptive clause in the treaty would spark passionate claims of sovereignty from both countries.

Warbass was keenly aware of the changing political landscape and the influence of the Hudson's Bay Company which, for a time, he served as agent. He had his initial experience in public service when he served as the first auditor and treasurer of Lewis County, then part of Oregon Territory. It was at his store at Warbassport in 1851 that the Columbia Territory Commission met and resolved to petition Congress to create a separate territory north of the Columbia River, a governmental change which Congress approved in 1853, establishing Washington Territory. Warbass lived in the town he had fostered for three more years, and when conflicts with Indian tribes threatened in 1855, he was commissioned by the first Washington territorial governor, General Isaac Stevens (1818-1862), as a captain leading a force of volunteers charged with protecting the important Cowlitz River corridor.

Post Sutler

By 1856 Warbass was eager for a new adventure when he was appointed by the United States Secretary of War to the position of post sutler (or storekeeper) for the newly established Fort Bellingham on the young territory's northwestern coast. The sutler's cabin was outside the walls of the fort on a trail down to the water southwest of the block house. Also outside the palisade were the officers' mess, laundry, shops, and hospital. Inside the palisades, about 80 yards on a side, were a mess hall, kitchen, bakery, barracks, and officers' quarters. The fort, under the command of Captain George Pickett, seems to have operated under rather lax discipline, and, more than once, the store was broken into and items stolen, although none of the soldiers was ever disciplined.

The sutler was important not only for provisioning but also for the morale of the officers and men of a western fort and often for the settlers in the nearby area. The army commissary provided only absolutely necessary supplies such as beef and flour, tents, shirts, and blankets. "All further personal commodity needs of the troops, real or fancied, required other means. To fill the gap, a civilian merchant, through his official appointment as sutler, was allowed to open up a general store with the exclusive privilege of trading with the garrison" (Davis, 38). Items such as canned food, candy, towels, tobacco, whiskey, beer, ready-made clothing, combs, and needles and thread were especially popular. The sutler would even take large special orders, although the flow of goods could be rather slow from eastern suppliers. The sutler might also perform some banking services, as "the store was often the only agency where an individual [could] obtain credit, borrow money, deposit sums for safekeeping, or arrange for remittance to other areas" (Davis, 45).

San Juan Island and a Destructive Pig

Even before Warbass arrived at Fort Bellingham, the British, primarily through the Hudson's Bay Company, were continuing to develop their interests in the Pacific Northwest. After the Oregon Treaty of 1846 the headquarters of HBC had moved from Fort Vancouver to Britain's military and governmental base of operations at Fort Victoria, founded in 1843 on the southern tip of Vancouver Island. Just east, easily visible across the water, was San Juan Island, one of a group of islands between the U.S. mainland and Vancouver Island. As early as 1851, HBC had established a salmon-salting station on San Juan Island to process fish purchased from Native Americans.

The island was viewed by James Douglas (1803-1877), then British Crown Colony Governor on Vancouver Island and the chief factor of HBC, as of strategic importance in safeguarding the waters for British commerce and movement from the settlement of Vancouver, on the mainland coast of British Columbia, south and then west out the Strait of Juan de Fuca to the Pacific Ocean. To fortify the British claim to San Juan Island and discourage American settlement, the government encouraged HBC to colonize. "The San Juans with their acres of virgin prairie beckoned. Douglas advised the colonial office that the San Juans could 'maintain a large population' because of the extent of timber, arable farmland, and fisheries" (Vouri, The Pig War: Standoff ..., 33). Charles Griffin (1827-1874), an HBC agent, was sent to establish Belle Vue Sheep Farm in 1853, and by 1859 HBC settlers numbered 29 (19 employed by Griffin), farming 80 acres of oats, peas, and potatoes. Livestock included 4,500 sheep, 40 cattle, five yoke of oxen, 35 horses, and 40 hogs.

But Americans were finding the island an appealing place to settle as well. A brief gold rush on the Fraser River in British Columbia had enticed many to seek their fortunes, but a number of discouraged prospectors eventually turned south and took up homesteading on San Juan Island. By 1859 there were 18 Americans settled on grazing land claimed by HBC. They, of course, felt that they owed allegiance to, and were under the protection of, the United States. When disputes arose between the British and American settlers, each group looked to its own government for support. That year one of Charles Griffin's prized, but free-roaming, Berkshire hogs invaded a potato patch belonging to Lyman Cutlar, an American settler. It was not the first time, and in extreme frustration at the all-too-frequent destruction of his vulnerable, unfenced garden, Cutlar seized his gun and shot the pig. Recognizing that his actions were undertaken in the heat of the moment, he went to Griffin and offered to pay for the pig; Griffin claimed that it was a special and extremely valuable animal and demanded $100 which Cutlar thought was outrageous, and which he refused to pay.

Griffin appealed to the British authorities who threatened to arrest Cutlar and evict all of the American settlers from land that the British claimed belonged to HBC. In response, the American settlers wrote to the military commander of Oregon Territory for aid. He, in turn, ordered Captain Pickett and the garrison at Fort Bellingham to depart immediately for San Juan Island to enforce American claims and support the American settlers. On the evening of July 26, 1859, Pickett and his troops sailed into San Juan Harbor, a shallow bay on the southeast coast of the island. Among those on board the ship was the garrison sutler, Edward Warbass. The next morning they disembarked at a wharf constructed and claimed by HBC.

The British were incensed. The Victoria newspaper noted indignantly that "the all-absorbing question of the day is the clandestine landing of United States' soldiers on San Juan. No notice of their intention to take so unwise and impolitic a step was given to our government. But, like thieves in the night, they sought to plant themselves on an island over which we have exercised sovereignty many years, and to which, by every rule of right, and by a clear interpretation of the Treaty of 1846 we are lawfully entitled. We cannot but characterize this reckless attempt to endanger our peaceful relations, and possibly precipitate us into a war, as other than an act of treason to the age and mankind" ("The Topic ...").

The problem was that vague description in the Oregon Treaty of 1846 that could not, in fact, be clearly interpreted, as it did not recognize that there were at least two bodies of water that could be considered "the channel which separates" the mainland of the United States and Vancouver Island, one on each side of the San Juan archipelago. The British claimed that the waterway east of the islands, today's Rosario Strait, marked the limit of their territory, while the Americans claimed that the western channel, Haro Strait, was the boundary, and therefore the San Juan Islands were within United States jurisdiction.

Pickett wasted no time in setting up camp on San Juan Island not far from the split-log wharf and San Juan Town, a village of less than two dozen buildings where "the four B's of Booze, Broads, Beer, and Brawls held sway" (Crawford, 105-6). Just a few days after the landing, British visitors observed Warbass constructing a log building with stacks of provisions piled nearby awaiting the store's completion. In the next months, Warbass was declared by the U.S. military commander as the sole provisioner on the island, serving the military, settlers, Indians, and visitors alike.

Tensions between the two countries increased as some American military commanders and Douglas looked for excuses to escalate hostilities from verbal to armed combat. Fortunately, neither the British naval commander nor United States President James Buchanan (1791-1868) or General Winfield Scott (1786-1866), sent by Buchanan to intervene in the dispute, wanted to go to war over the mere shooting of a pig. Victoria's Daily Colonist expressed relief: "For a brief space, 'a speck of war' hung, meteor like, upon our northern border, but thanks be to wise heads and human hearts, it is now below the horizon, and 'tis hoped will rise no more" (December 15, 1859, p. 2).

Settler

The more he saw of San Juan Island, the more attractive Warbass found it as a place to put down roots. Because civil government on the island was almost nonexistent as long as the boundary issue remained unresolved, proper registration for homesteading was impossible, so early settlers took up squatters' claims on island property. Warbass purchased a farm including a farmhouse and prepared to develop his new property but found that he was competing with other claims that overlapped his. Although one of the claimants attempted to take him to court over the matter of ownership, the American military government dismissed the justice of the peace, and the matter never came to trial.

Warbass quickly became a well-regarded member of the community at a time when the total island population was so small that his reputation was spread through almost daily encounters in his store with both American and British military personnel and settlers. According to an account published in an island newspaper decades later:

"The officers of both camps grew to love and respect the sturdy sutler, and this respect they cherished for many years afterward. He secured a large portrait of Gen. Pickett ... . [In later years] other pictures were sent to him by both the British and American officers, and usually each piece was backed by some message of endearment" ("Monuments ...").

From the American point of view the San Juan Islands, often designated the "disputed islands" in census and other official documents, were nominally considered part of Whatcom County, and in 1860 Warbass was elected as the island's representative from Whatcom County to the territorial legislature. In 1862, as the settlers chafed under the often erratic and seemingly arbitrary rulings of the current justice of the peace (who conducted business from a San Juan Town barroom), Warbass was entrusted by his fellow islanders with the task of composing a letter to the military commander at Fort Vancouver asking for redress. "'American settlers would be contented to have the laws of Washington territory in full force, and with rigid vigor executed,'" he assured the commander, "'but are prepared to believe that the general will agree with them that under the law as executed by Mr. [E. T.] Hamblet we have something other than the laws of our country'" (Richardson, 119).

In 1864 Warbass went south to Oregon with the intention of purchasing sheep to stock his homestead. The expedition did not go as planned; adventures intervened; and Warbass did not return to the island until 1872, just as the boundary dispute was being decided, through the mediation of Kaiser Wilhelm I (1797-1888) of Germany, in favor of the United States. When islanders protested the personal property taxes immediately imposed by Whatcom County on its newest residents (the islands no longer being in dispute, but now an official part of Whatcom County), Warbass strongly concurred that the islands should be able to fix their own taxes and handle their own affairs. Within months, Warbass organized an effort to have the Whatcom County representative in the territorial legislature push through a law creating a separate San Juan County, the smallest in the territory. By 1873 he had homesteaded property on behalf of the county government for establishment of a suitable county seat on Friday's Bay, named for the HBC sheepherder who had tended his flocks on the prairie just to the west. The peaceful shore of this deep, tree-lined harbor on the island's east coast several miles north of rowdy San Juan Town seemed to Warbass to be an excellent site for the county government offices, for commerce, and for family settlement.

During the next 33 years until his death in 1906 at the age of 81, Edward Warbass continued to play a variety of important roles in the development of the community of Friday Harbor and of San Juan Island. He brought the first post office to Friday Harbor, served as the first county auditor, was a justice of the peace, and served as the deputy collector of customs at Roche Harbor on the north end of the island. He was active in politics and took a firm stand against the small group of Republicans who, he felt, took insufficient care in using taxpayers' funds and were determined to maintain control for their own interests against the will and well-being of the citizens of the county. He homesteaded land at the border of Friday Harbor where he lived in the house that had been Captain Pickett's residence at American Camp -- dismantled, moved and rebuilt. There he entertained friends, developed commercial interests, and, in his last years, enjoyed the status of a well-respected and cherished community elder. Although he certainly could not have foreseen its importance, the day he first stepped ashore on San Juan Island marked the beginning of a long and distinguished life as one of the island's most esteemed pioneers.