On November 25, 1899, The Seattle Star reports that Wyatt Earp (1848-1929), an "ex-sheriff from Arizona," is preparing to open a new gambling house in the infamous part of town south of Yesler Street known as the tenderloin. The following week Earp does just that, partnering with Tom Urquhart (1856?-1933) in the Union Club, near 2nd Avenue S and Washington Street. Despite opposition and threats from the owners of the city's other formal gambling houses, most of which make regular payments to police and politicians, the Union Club is an immediate success. But Earp's stay in Seattle will be short, and troubled by sporadic enforcement of the city's anti-gambling ordinance. He has other business interests, legitimate and less so, ranging from Alaska to Los Angeles. Within months Earp divests himself of his interest in the Union Club and leaves Seattle with his wife to continue their wandering lifestyle. The club will carry on for a brief while under Urquhart's ownership, but will later be closed for good when state law enforcement steps in to end illegal gambling, at least temporarily.

Not Yet a Legend

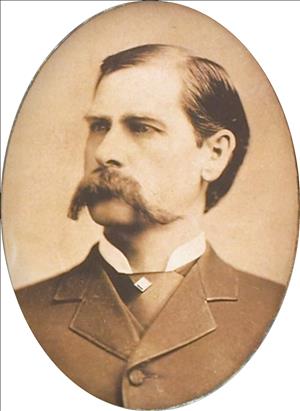

There seem to be as many versions of Wyatt Earp's life as there are writers of it. It is undisputed that he was born in Monmouth, Illinois, on March 19, 1848, to Nicholas Earp (1813-1907) and Virginia Cooksey (1821-1893) and that he had three older brothers and a younger half-brother. Before Wyatt was one year old the family headed for California, but got no farther than Iowa, where his father farmed for several years before returning with the family to Illinois in 1859. The Earps finally made it to California in 1864, ending up in the San Bernadino Valley.

After a marriage in 1870 that ended with the death of his wife nine months later, probably during childbirth, Wyatt Earp spent many years roaming the Southwest, working both sides of the law. A biography published in 2013 noted that "When he was not wearing a badge, he was variously a thief, brothel bouncer, professional gambler, and confidence man who specialized in selling gold bricks that were nothing more than rocks painted yellow" (Isenberg, 8).

In this Earp was no different than many young men on the frontier who were only as honest as they needed to be and frequently found it necessary to outrun their reputations. This became more difficult with the advent of better communications, but for decades Earp managed to conceal his most disreputable actions with remarkable success. It was not until long after his death that serious scholarship began to tease at least some of the facts from the tangle of myths and half-truths, many of his own making, that were left in his wake.

In the early years of the twentieth century Earp's travels took him to Los Angeles, where he became acquainted with people working in the young Hollywood movie industry, including screen cowboy William S. Hart (1864-1946). Hart persuaded Earp to record a memoir, and over the next 20 years or so he more or less cooperated with at least three hopeful biographers. The efforts of the first did not please him and the second manuscript was so poorly written as to be unpublishable. But late in his life a third writer, Stuart N. Lake (1889-1964), interviewed Earp at length for a biography. In 1931, two years after Earp's death, Lake's Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshall was published. It was only then that the "Gunfight at the OK Corral" in Tombstone, Arizona, became a mythic event of the American West and Earp the most famous icon of upstanding frontier law enforcement. He had outlasted most of his contemporaries and there were few or none left to dispute Lake's account. The book was later the primary source for several movies and a popular television series in which, almost without exception, Earp was portrayed as a nearly unblemished heroic figure. It didn't hurt that even in old age he looked the part, but Lake admitted that much of his "biography" of Earp, particularly direct quotes attributed to his subject, had been invented to compensate for Earp's one-syllable answers and fading memory. While Lake's biography was a best-seller, later research has cast serious doubt on its accuracy.

A Sporting Man

Earp had a reputation among the reading public before Lake's hagiography was published, but it wasn't great. The October 26, 1881, shootout at Tombstone that later became central to the Earp mythos was recounted in The New York Times in a brief and factual report a mere two days after its occurrence, just one gunfight among countless others that plagued frontier towns and mining camps. In 1898 the Seattle Post-Intelligencer would characterize Earp as "one of the best known sporting men in the United States," a euphemism for the free-living, hard-drinking hedonists of the day who made their way by gambling and other disreputable pursuits ("Sports and Pastimes").

Earp rarely stayed in the same place for long, frequently becoming broke, bored, unwelcome, or some combination of the three. Over decades he roamed from as far south as the Mexican border to as far north as Alaska. For most of his years he did not roam alone, but was accompanied by his longtime common-law wife, Josephine Sarah "Sadie" Marcus Earp (1861-1944). Born into a German Jewish family in Brooklyn, New York, Sadie (called "Josie" by some) ran away from home at age 17. Two years later she was living in Tombstone with a man, but she soon abandoned him in favor of Earp. After that, "For forty-seven years, they roamed the West, mingling with well-known westerners on both sides of the law. Her name was rarely in print until her published memoir revealed an overlooked western folk female hero, long on daring, short on propriety" ("Josephine Sarah Marcus Earp, 1861-1944"). She may have been a prostitute and was almost certainly a showgirl, but she remained Earp's steadfast companion until his death in 1929.

GOLD!

The steamship Portland arrived in Seattle from Alaska on July 17, 1897, bringing with it the first large haul of gold from the banks of the Klondike River in Canada's Yukon Territory. This kicked off an era of prosperity for Seattle and King County that would last more than a decade. It also brought hordes of men and more than a few women seeking their fortunes by mining for gold, or by mining the pockets of those who mined for gold. Two of the more lucrative trades were prostitution, often called the world's oldest profession, and gambling, surely one of its oldest pastimes. Both were illegal in Seattle during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but the laws were enforced only sporadically.

Gambling boomed with the Gold Rush, and pushed by reformers, ministers, and parts of the local press, Seattle's authorities finally cracked down in April 1899. But by September of that year several gaming clubs were again open, running smoothly, and highly profitable. Several were controlled by one man, John Considine (1868-1943), who had ownership interests in at least three of the major gambling venues and made regular payoffs to the police and, with barely more discretion, to pliant politicians. Although there was some competition, the sin fraternity in Seattle was dominated by Considine and a small handful of like men who mostly stayed out of one another's hair.

Earp Comes to Town

Earp's first documented appearance in Seattle was in October 1897, when the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported that he and Sadie were passengers on the vessel Seattle, which had arrived from Alaska. They stayed at the Occidental Hotel and were to travel on to San Francisco, but had plans to open a sawmill at Lake Linderman in northern British Columbia. On June 4, 1898, he was back again, now reportedly on his way to Dawson Creek in gold-rush country.

On November 13, 1899, the Post-Intelligencer reported that Earp had arrived in Seattle from Nome, Alaska, two days earlier aboard the steamship Cleveland, again accompanied by his wife. Something was clearly afoot, as "since his return Mr. Earp has been much about the city in company with local sporting men, with every one of whom he is personally well acquainted" ("Wyatt Earp on Cape Nome"). It was also mentioned that Earp owned in Nome a combination saloon, club room, and hotel.

The November 25, 1899, article with which The Seattle Star greeted Earp's arrival was a breathless and hyperbolic account, but remains the most complete contemporary version and is worth repeating in its entirety:

EX-SHERIFF FROM ARIZONA TO OPEN GAMBLING HOUSE

John Considine's Combine Greatly Disturbed Over the Outlook

THE NEW MAN REFUSES TO PUT UP

Says He Will Run in Spite of Opposition -- Won't Knuckle to Chief of Police Reed or Anybody Else

Racy Developments

"The clique of boss gamblers in Seattle is badly disgruntled over the threatened appearance of an ex-Arizona sheriff in the role of a competitor. He proposes to go into the gambling business here with a partner, defying the Considine 'combine' and absolutely refusing to pay tribute to John or the city officials.

"The name of this new disturber of the tenderloin peace is Wyatt Earp, a man of great reputation among toughs and criminals inasmuch as he formerly walked the streets of a rough frontier mining town with big pistols stuck in his belt, spurs on his boots and a devil-may-care expression upon his official face. As sheriff he was the terror of the county and his fame as a quick and sure shot was known round about for many miles.

"Not long ago Earp, who has extensive mining interests in Alaska, came to Seattle to look over the ground with a view to opening a big gambling establishment. He found the Standard, White House and Clancy's making big money and quickly concluded that he would take a whirl at the business himself. So he called upon Tom Urquhar [sic], a well known sporting man who was formerly connected with Clancy and Burns and made him a proposition that involved a partnership and the opening of an eight-game house right in the heart of the tenderloin. Tom was nothing loath, feeling that he had a good man in Earp, so the two concluded a deal, which is now about to be put into execution.

"The place selected is the building of the old California club on Washington street. The time fixed for opening is next week, probably Monday or Tuesday. In view of the fact that a big business is anticipated 50 men will be employed about the premises, including the indispensable 'boosters.' Profits of from $15,000 to [illegible] a month, over and above all expenses, may be reasonably be expected.

"Soon after Earp's determination to open a gaming house was ascertained, the Considine combine sent a representative to the ex-sheriff to tell him that such doings could not be permitted in Seattle, and that it was the [better] part of wisdom for him, if he really intended to operate, to see Chief of Police Reed and arrange matters. They figured that the chief would promptly inform Mr. Earp that he wasn't an acceptable person and must seek elsewhere for pastures green.

"The man from Arizona was not to be bluffed, however. He refused to await the return of Seattle's missing chief of police and said, moreover, in brusque accents, that he wouldn't put up a bean to quiet the wrath of city officials. 'You fellows are paying enough, why should I add any money?' was his unfeeling response to a critical query. 'If Reed closes me up, he will have to close you all up too. See!' They saw, and that is what makes so much blue sulphur smoke in the atmosphere nowadays in the vicinity of the Standard gambling house, where the hush money is collected each month.

"Of course Earp expects a war to the knife to be waged upon him by the combine, but as his fighting powers are said to be so good and his wind excellent, the chances are that he will put up a pretty strong defense, and may come out the winner" (The Seattle Star, November 25, 1899).

About a week later the more staid and reform-minded Seattle Times, showing far greater restraint, announced Earp's arrival in a two-sentence item buried on page 8, noting that his "career in Arizona as a 'bad man' is well known" ("Wyatt Earp Here"). The characterization "bad man" was in that era specifically synonymous with "villain" and "desperado" (Dictionary.com).

Here and Gone

Earp and Thomas Urquhart opened their Union Club before the end of November 1899, and to the consternation of Considine and his cohorts, it was an immediate success. The Seattle Star reported on December 13, 1899, that "Earp and Urquhart's new house, the Union Club 112, is having a large patronage. When it was first opened about two weeks ago five games were run. Last night the management placed several new games on the floor" ("Gamblers' Fines Aggregate $1,200").

As the headline of the article indicated, Considine's system of bribes, no more legal than the gambling it protected, had been normalized by characterizing at least some of the payments as "fines." Despite Earp's defiant claim on November 25 that he would not "put up a bean to quiet the wrath of city officials" ("Ex-Sheriff from Arizona ..."), the newspaper reported that the Union Club had paid a fine of $175. But, it added, "The Seattle gamblers are reaping a harvest. Their monthly fines are trifling compared with their enormous profits" ("Gamblers' Fines Aggregate $1,200").

A detailed account of Earp's months in Seattle at the turn of the century has proved typically elusive. Different sources put the location of the Union Club at slightly different locations, and there does not seem to be a record of exactly when Earp divested himself of his interest in it. In fact, two of the most recent and well-researched Earp biographies don't mention his time in Seattle at all, perhaps because it was one of the least exciting or least notorious episodes in a long and adventurous life.

Some inferences can be taken from known facts, however. There was a brief crackdown on gambling in the early months of 1900, and on January 25 that year The Seattle Times reported that Charles Clancy, who owned the Clancy House gambling club with his brother John, had been arraigned on charges of running "a Chinese lottery." It is not clear why this particular form of illegal gambling was not tolerated in a town where poker and faro games were, but the paper, quoting no sources, opined that the bust was "due to a fight among the gamblers. Bitter war is threatened" ("Clancy Arraigned").

That seems to have been at least partially true. The Clancys were not part of Considine's gambling "trust" or "combine," as it was often characterized in the press. On January 28 they retaliated by filing criminal complaints against two of Considine's houses, the Standard and the Horseshoe, which led to them being shut down. There clearly was skirmishing going on among the city's sporting men, but not everyone was yet involved. As the Post-Intelligencer reported:

"Two gambling houses — the California Club and the Earp-Urquhart club, were unmolested, but the statement was made from a reliable source yesterday that the only reason their proprietors were not arrested was because the Clancy faction believed they would close of their own accord" ("Gambling Rooms Closed").

They didn't, and both the Standard and Horseshoe clubs reopened on February 1 after paying small fines. But Earp's Union Club was in someone's crosshairs. The article in the Post-Intelligencer that announced the reopening of Considine's clubs also reported: "It was learned yesterday afternoon that an ex-constable was at work securing evidence upon which it is proposed to swear out warrants for the California Club and the Earp-Urquhart house. It could not be ascertained who was behind the movement" ("Gambling Houses Opened").

The Clancys, angered that the rival clubs had reopened, threatened to take their complaints to the state attorney-general and apparently carried through on it. In March 1900 state law enforcement stepped into the fray. Citing court records, an article in the October 2007 issue of Wild West magazine indicated that Earp, while still possibly a partner in the Union Club, had left Seattle:

"On March 23, 1900, the state of Washington filed charges in the Justice Court against the gamblers; among others, 'Tom Urquhart and Dave Wyatt [sic] Earp' were charged with 'conducting as proprietor a certain gambling game.' Each gambling house was served separately. Warrants were issued, and Urquhart was served, but no mention is made in the court record of Wyatt being served ... . After a couple of continuances, Urquhart, through his attorney, pleaded nolo contendere. Urquhart was fined $75" (Potter).

It seems probable that Earp had concluded that running a gambling house in Seattle was more trouble than it was worth, and that he had left town before the state warrants were issued. It was certainly not the first time, and likely not the last, that he was a step or two ahead of the law.

The next mention of Earp to come to light in the popular press was in the April 30, 1900, edition of The San Francisco Call, where it was reported:

"Wyatt Earp, gun-fighter and all around bad man, was knocked down and out late Saturday night by Tom Mulqueen, the well-known race horse man. The trouble ... was precipitated by Earp. Both men had been drinking ...

"Earp was not armed at the time, having left his trusted 'gun' with a friend shortly before the occurrence" ("Gun Fighter Is Knocked Out ...").

Clearly, Wyatt Earp at the age of 52 was still a "sporting man," if perhaps no longer quite as "bad" as he had once been.

An apt coda to the Earps' Seattle stay appeared in a Wild West magazine article of October 2007:

"In the spring or summer of 1900, Wyatt Earp was back in Seattle with his wife, Sadie, to catch the SS Alliance and return to his saloon in Alaska. Seattle was again a wide-open town with saloons, gambling, fast women, sporting events on which to bet and the camaraderie of the sporting crowd. Rules were made to be broken in Seattle, and the tenderloin was the place to break them. Wyatt Earp, though, was only a transient character in the tenderloin’s history. He entered the Seattle gambling fraternity with passion, fortitude and resilience, and he slid out with nary a whisper" (Potter).