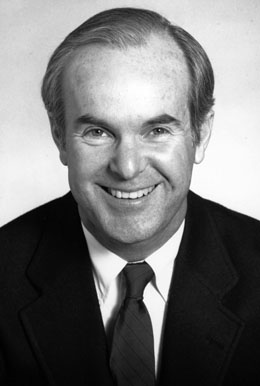

On August 4, 1989, Governor Booth Gardner (1936-2013) and 26 Washington tribes sign the Centennial Accord. The accord affirms the sovereignty of Washington's federally recognized tribes and calls for clearer communication and better collaboration between tribal and state governments. It marks one step forward in a long history of conflict between the tribes and the state dating back to the 1850s, a conflict that came to a head in the fish wars of the 1960s and 1970s. Federal courts affirmed the tribes' fishing rights in 1974, but the state continued to fight the rulings until the early 1980s. It eventually became clear that the only path forward was to recognize tribal sovereignty and develop new relationships and strategies to co-manage the state's fisheries and to resolve other intergovernmental conflicts. Building on the cooperative efforts around salmon management, Gardner called for a change in state policy to actively facilitate the government-to-government relationship between the state and the tribes. Tribal leaders agreed to work with the governor and other state agencies, and the Centennial Accord is negotiated and signed. Although it does not resolve all state-tribe conflicts, it shifts the direction of state policy and sets the stage for improving government-to-government relationships.

Fishing Rights, Fish Wars

After decades of challenges to the application of state laws to tribal fishing, laws which infringed on treaty-reserved fishing rights and tribal sovereignty, the tribes resorted to civil disobedience to force the courts to deal with the issue. Judge George Boldt (1903-1984) heard the arguments in United States v. Washington and handed down a ruling in 1974 that opened a new chapter in government-tribal relations in Washington state. Known popularly as the Boldt Decision, it affirmed the tribes' treaty-reserved right to fish in their usual and accustomed places. Further, Judge Boldt interpreted treaty language stating that the tribes' rights were "in common" with non-Native fishing as guaranteeing the tribes one-half of the annual catch of salmon and other fish species in Washington waters.

The state appealed this decision, arguing that the state could use fishing regulations to limit tribal fishing rights in the interests of conservation. The appeal worked its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which upheld the Boldt Decision in 1979. Several years of skirmishes followed over how to implement the co-management called for in the ruling, with state agencies repeatedly trying to limit tribal involvement.

A New Approach

Agency staffs and elected leaders eventually realized that this approach was not working and only resulted in rising court costs and delayed implementation of any sort of cooperative agreement. Tribal leaders realized that relying on the courts would not provide a solid foundation for securing their rights -- each new case would be subject to changing political attitudes, and previous gains could be reversed by later decisions.

Instead, both sides looked to establish a new relationship between the state and the tribes. In his announcement of the Centennial Accord, Governor Booth Gardner said, "The tribes are sovereign governments and should be treated as such. It is in our interests to improve the ability of both tribal and state governments to perform as governments. State government will no longer be an obstacle to tribal sovereignty" (Annual Report). Joe DeLaCruz (1937-2000), president of the Quinault Indian Nation, remarked, "The accord is designed to address issues through cooperation and negotiation rather than confrontation and litigation" (Annual Report).

The Centennial Accord

The accord called for recognition of tribal sovereignty and for state agencies to develop systems for communication with the tribes and for cooperation in decision making. These interactions between state agencies and their counterparts in tribal governments would make the government-to-government relationship more effective and more firmly established. At the executive level, the Governor's Office of Indian Affairs would facilitate implementation of the accord and foster the relationship between the state executive and tribal leaders.

Governor Gardner and tribal representatives gathered at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle on August 4, 1989, to sign the accord. In the years that followed, agency and tribal staff made progress in improving state-tribe relationships and communications. Agreements have been made on issues large and small, and tribal and state representatives meet annually to discuss additional issues and seek solutions. In a 2014 announcement of the Centennial Accord summit, Jamestown S'Klallam chair Ron Allen is quoted: "We have not accomplished all our goals, but this commitment has resulted in a solid progressive foundation to advance improvements in most areas of Tribal concerns, including natural resource management, education, health care, economic development and social/community affairs" ("State and Tribal Governments to Convene at Evergreen for 25th Accord").

The Centennial Accord put Washington at the forefront in addressing how states should recognize and honor the treaties the federal government made with tribal nations in the nineteenth century. A number of other states have signed similar accords with the tribes within their borders. Alaska's Native leaders signed the Millennium Agreement with that state's government in 2001. In the same year, Oregon's state legislature passed a bill requiring the state to work with tribes to improve communication and develop government-to-government relations. In 2003 and 2004, governors in Minnesota and Wisconsin signed executive orders related to tribal sovereignty.

Reaffirmation

On November 4, 1999, Governor Gary Locke, Attorney General Christine Gregoire, and tribal leaders gathered at Leavenworth and reaffirmed their continuing support for the Centennial Accord by signing the Millennium Agreement. This pact restated the goals of the original accord and recommitted the signatories to a number of goals:

- Strengthening the government-to-government relationship between the state and tribal governments;

- Cooperating and communicating more effectively;

- Developing a consultation process;

- Strengthening the Governor's Office of Indian Affairs and the Association of Washington Tribes;

- Encouraging the state legislature to codify a structure for addressing issues of mutual concern;

- Educating state residents about tribal history, treaty rights, and contemporary tribal governments to increase understanding of why the government-to-government relationship is important;

- Working to reduce discrimination and prejudice against Native people;

- Cooperating to resolve natural resource, economic development, and social and community service concerns.

The federal treaty makers of the nineteenth century, particularly Territorial Governor Isaac I. Stevens (1818-1862), did not anticipate the tenacity of Native people in Washington in surviving and thriving in the face of federal policies designed to undermine their cultures, governments, and economies. Nor could they foresee the dire environmental consequences of unfettered resource use and the changing legal landscape of the late twentieth century. State and tribal personnel tasked with forging a path forward face a difficult task, but they continue to work on collaborating effectively to solve disputes.