Smallpox struck New Tacoma, a recently platted town encompassing much of what later became downtown Tacoma, in October 1881. The outbreak sickened an official count of 80 people and killed 14 by the time it ended that December. It also divided the local medical community, inspired the creation of the city's board of health, and provided a new role for the veteran Mosquito Fleet steamer Alida.

A Fearsome Disease

The disease came just as business prospects were looking up for New Tacoma. Platted in 1875 to provide a town at the chosen site of the Northern Pacific Railroad terminus, it had been in competition with the original Tacoma settlement, located three miles to the northwest in what is now the Old Town neighborhood, ever since. In 1880 Pierce County voters named New Tacoma the county seat, replacing Steilacoom and further salting the wounds of the original Tacoma City, afterward inevitably referred to as Old Tacoma. (The two separate towns were merged in 1884 into the single city of Tacoma.)

At first, New Tacoma's position as the railroad terminus had provided little actual benefit, since the Panic of 1873 stalled railroad construction. But on October 4, 1881, the thousand New Tacomans had hosted the Northern Pacific's new owner, Henry Villard (1835-1900), and were hoping to see tracks laid across the Cascades soon. Dr. Henry Clay Bostwick (1828-1916) had co-founded the city's first bank in October 1880 and was busy making real estate loans. Then it all came to a halt.

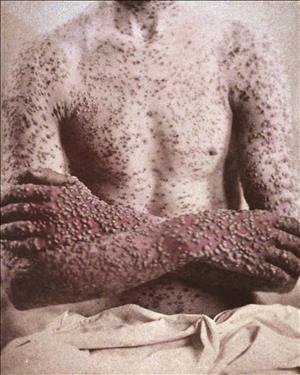

Smallpox (Variola major) was the most feared disease of the nineteenth century due, to its extremely contagious nature and high fatality rate in its severe forms. The viral particles that cause the disease can be launched into the air by "a single breath, cough, laugh, sigh, or spoken word" (Willrich, 26). Survivors were likely to be disfigured and sometimes blinded by scars. An incubation period of up to two weeks meant that a traveler from an affected area could show up in town seemingly in perfect health, only to fall ill and become contagious after arrival.

A Reluctant Diagnosis

The first official smallpox case in New Tacoma that fall was John Thanen, a waiter at the Halstead House on Pacific Avenue. He fell sick in the first week of October, soon after serving the midnight supper at the installation ceremony for the first Tacoma chapter of the Knights of Pythias. His father-in-law and his four children also were infected, and the father-in-law died. Other suspected cases had already been noted, but an official diagnosis was delayed. As happened in many communities, residents were reluctant, for both business and personal reasons, to admit the presence of the disease. Smallpox in its milder form could be mistaken for chickenpox, and many were eager to do so.

Dr. Bostwick, along with Drs. E. F. Miles and A. M. Ballard (d. 1916), all diagnosed the early patients as having severe cases of chickenpox. Dr. Francis Bond Head Wing (1838-1882), the newest medical arrival and Bostwick's partner in practice, said they had smallpox. He was ridiculed by the more established physicians, and on October 28, the Tacoma Ledger printed a letter signed by Bostwick and Ballard announcing that they, "for the purpose of placing the public at ease, and correcting false reports, desire to say that there is not nor has there been any smallpox in this town this season" (Radebaugh).

Not long thereafter, Wing and Bostwick announced the dissolution of their joint practice. As cases and deaths accumulated, the city began to face reality. Recently elected Mayor David Lister (d. 1894) asked Seattle's health officer, Dr. E. L. Smith, to come to town and settle the disagreement. He saw 15 patients and diagnosed them all as having smallpox. He billed the city $120 for the bad news.

A Civic Response

Once Smith made the epidemic official, New Tacoma's common council moved quickly to set up the legal apparatus for providing and paying for its management. On November 2, the board appointed Wing as New Tacoma's first health officer. His powers included the right to require and administer vaccinations, to flag houses and buildings sheltering patients, to bill the city for supplies and services, and to establish quarantines. Anyone thought to have an infectious disease or who was nursing a contagious person was forbidden to "appear on any street or alley of the town, nor shall they approach or mix with other persons" without a certificate from the health officer or attending physician (New Tacoma Ordinance No. 40). Penalties ranged from $5 to $50.

The supervisors' actions were authorized by legislation passed just that year by the territorial legislature. The Miller Bill gave municipalities power "to isolate disabled patients, to force the ambulatory sick to leave town, to quarantine ships, to confiscate infectious articles and baggage, and to inspect incoming travelers" (Saddlebags and Scanners, 59).

Although a vaccine for smallpox had been available in the United States since 1802, vaccination was not mandatory in Washington Territory at the time. Even in places where it was required, public (and sometimes political) resistance to vaccination mandates was fierce. And indeed, the vaccines of the time had side effects ranging from an arm that was sore enough to keep a working person off the job for weeks to infections and sometimes death. Thousands of soldiers during the Civil War were rendered unfit for duty not because of smallpox itself but because of other diseases, including syphilis, contracted from contaminated vaccines. Especially if they had not experienced the terror of an outbreak, many people were willing to take their chances that they would only get the milder form or would escape the disease entirely. Wing was given the power to order vaccinations, and people who refused could be found guilty of a misdemeanor. The city agreed to pay if a person could not afford the shot.

A Confusion of Cause

There was little understanding of the cause of smallpox. People blamed miasma (bad air) or dirty living conditions. William P. Bonney (1856-1945) converted a room in his Pacific Avenue drugstore to fumigate worried Tacomans. For 25 cents, customers would sit in the room as it filled with smoke from burning sulfur, breathing through a hole Bonney had cut in the door. Bonney also sold tin boxes filled with carbolic crystals, which the buyers carried in their pockets.

Given the prevailing "bad air" theory, Wing inspected the "privy vaults" (open cesspools) in the business district and delivered a scathing report, saying that they were "in a vile condition and extremely dangerous to health," and asking the supervisors to force business owners to remove the excrement and replace the privies with "earth closets" designed to add a layer of soil after each use ("Minutes").

Wing used his authority to acquire the mothballed Mosquito Fleet steamer Alida as a floating hospital. It was anchored in Commencement Bay and staffed by nurses. Wing made the two-mile trip by rowboat to treat patients quarantined there, including an entire indigent family of seven, only two of whom were actually sick.

In addition to his Tacoma patients, Wing traveled to the nearby Puyallup Reservation and as far as Orting some 20 miles southeast of Tacoma to see the sick. He monitored the quarantines, ordered and invoiced supplies, kept records of diagnosed cases and deaths, and reported regularly to the common council.

A Closed City

Commerce and much of daily life came to a halt in New Tacoma. Schools and churches closed. Trains passed through without stopping, their windows boarded up. The literary society interrupted its schedule of debates; district court was suspended; the post office stopped taking mail north from New Tacoma. Families caring for smallpox victims were confined to their homes and could not shop for groceries. They had to wait for deliveries, and the couriers were not allowed inside. Supplies were left on nearby stumps in the November rains, or else in the mud of the unpaved streets.

Rival communities were both frightened and gloating. On November 9, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer printed an item estimating 50 cases in Tacoma. The Ledger struck back against that "smug little item" [Radebaugh], countering that there were only five. The actual number at the time was probably closer to 20.

Old Tacoma's council, still smarting over New Tacoma's recent ascendency, held a public meeting on November 7. After "a few remarks of appropriate welcome and regret that such a serious matter as a discussion of quarantine on account of small pox should call them together," a Mr. Walters said that smallpox was "the only thing that New Tacoma ever had that it was willing to share with us" ("Journal of the Proceedings ..."). Speeches ensued by Howard Carr, Judge Botsford, and others, resulting in a call for a quarantine between the two towns. Carr was named sentry to guard the entrances to town. Puyallup and Steilacoom both posted armed guards on the roads to Tacoma, and train passengers from Tacoma were not permitted to get off in Puyallup. Seattle and Olympia established quarantines.

Without school, church, travel, or much ordinary commerce, the citizens of New Tacoma who were not sick or nursing patients had plenty of time to look for scapegoats. One was Dr. Ballard, who was blamed first for his initial denialism and then for his casual style. The supervisors sent him a letter:

"Complaint has been made by numerous citizens that you have not been sufficiently cautious to guard against and prevent the spreading of small pox in this community ... First, that you have been negligent in fumigating and cleaning and changing your clothing after visiting your patients, and that you are specially careless in permitting your dog to accompany you in your professional visits and then permitting him to run at large unrestricted " ("Minutes").

Tacoma's Chinese residents also got particular scrutiny. Smallpox was often blamed on whatever ethnic minority had a presence in a community, whether Chinese, Mexican, or African American. When a man died in a Chinese house near the railroad wharf, the owner was fined $25 for keeping the illness secret. The supervisors asked Wing to examine all Chinese houses daily, not a requirement for houses of whites, and fumigate as needed. In fact, Chinese workers took on some of the most dangerous jobs during the crisis, such as doing the laundry from hospitals and quarantined houses.

A Return to Normalcy

Vaccination and isolation did their work. Within a month, the outbreak had subsided. Seattle lifted its quarantine on December 10, Olympia and Tacoma City followed suit December 14, and Puyallup shortly thereafter. On December 21, Wing reported to the supervisors that he had discharged the last case from the Alida and had no one in the hospitals, "and I hope within ten days to remove the last yellow flag" (Radebaugh). He tallied a total of 80 cases, 23 of them occurring before the quarantine was enforced, and 14 deaths. Wing subsequently reported one new case on December 23.

The supervisors also considered invoices for goods and services pertaining to the outbreak -- including for the watchman, boatmen, and nurses from the Alida and for two Chinese washmen and wood for their washhouse boilers, along with $1 for yellow flags, 50 cents for kerosene, and 72 cents for apples for the hospital. They turned down a $240 invoice from Dr. Ballard, on the grounds that he was not employed by the city.

By December 23, the Ledger reported "a great revival in business in New Tacoma. The streets have been daily crowded with people, attracted thither to make purchases for the coming holidays, and the faces of merchants in consequence have been wreathed with smiles" (Murray Morgan notes). New Tacoma's last smallpox patient, Marshall Lowe, was released from the hospital on January 2, 1882.

A Tale of Four Doctors

Wing was widely praised for diagnosing smallpox in the first place and for his nonstop efforts combatting the disease. He had worked himself to exhaustion, aggravating a previously known heart condition, and his friends urged him to travel and rest. Planning a trip to San Francisco, he bought train tickets for January 15. He died in his bed the night before his scheduled departure. He was 43.

Ballard left Tacoma soon after the epidemic ended and moved to Asheville, North Carolina, where his fondness for dogs continued to cause comment. In 1914, a delegation of his neighbors went to the board of aldermen to complain about the incessant howling of his pets. When he died two years later, however, all seemed forgiven. His obituary lauded him as "the friend of dumb animals," who was "constantly surrounded by an assortment of crippled dogs, seeming to have a special preference for these pets and always being ready to take up the care of any stray cur. He also was noted for his charitable work among the poor people of the city. The night was never too dark nor the way too long for Doctor Ballard to answer a call, and he never presented a bill" ("Friend of Dumb Animals").

E. F. Miles, who was an Episcopal minister as well as a doctor, became the first resident physician and chaplain of Tacoma's Fannie Paddock Memorial Hospital, founded in 1882. In 1883 he moved to New York City, where he went to work at the Sunday school of St. George's Episcopal Church.

Bostwick, unlike Ballard, was not held back in Tacoma by his initial resistance to the smallpox diagnosis. He prospered as a banker until the Panic of 1893 and was a founder of the New Tacoma Board of Trade, which later became the Tacoma Chamber of Commerce. In 1888, he became president of the newly founded Pierce County Medical Society. He left town after the 1893 economic collapse and lived in Vancouver, Washington, until his death in 1916. His best-remembered legacy in Tacoma now is the triangular Bostwick Building on Broadway and St. Helens Street.

Smallpox itself was not done with the Puget Sound region. Seattle had an outbreak in 1892 that killed 19 people and was fought with 10,000 compulsory vaccinations. The last incidence of smallpox in Washington was in 1946. A serviceman returned from Japan incubating a case of Purpura variolosa, the highly fatal hemorrhagic variant of the disease. The infection spread from Seattle to the Olympic Peninsula, affecting 68 people and killing 22.