Peaceful Valley is a Spokane neighborhood known as a working-class, bohemian enclave located just west of downtown on the south bank of the Spokane River. It is separated from the rest of Spokane by steep hills and the wide river, giving it a character unlike any other Spokane neighborhood. The land was originally the site of the Spokane Tribe's most important fishing camps near the base of the Lower Falls of the Spokane River, but dams eventually cut off the salmon runs. As the city of Spokane grew, Peaceful Valley was slow to be developed because of the steep hills. It was first occupied by squatters and was known as Poverty Flats. Developers bought the land and renamed it Peaceful Valley after a stage play. Modest houses sprang up and it soon became the center of Spokane's Finnish community. In the 1960s and 1970s, Peaceful Valley became known as a counterculture haven. In recent decades, it has attracted new development, yet retains much of its historic character.

A Critical Resource

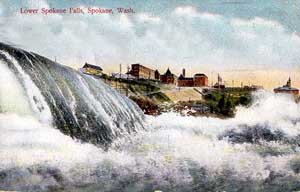

No site in present-day Spokane has ever matched Peaceful Valley in its importance to the Spokane Tribe. For millennia, the base of the Lower Falls of the Spokane River was the tribe's bustling -- and utterly crucial -- salmon-fishing camp. A second fish camp was just downstream, where Hangman Creek (also called Latah Creek) enters the Spokane River. These two sites now serve as bookends, east and west, for the neighborhood known as Peaceful Valley.

These fishing sites were crucial not only to the Spokanes, but to tribes from all over the region. They converged there to share in the incredible wealth of chinook salmon that spawned at the base of the Lower Falls. By some estimates, one million salmon made the run up the Spokane River every year. When Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809) and William Clark (1770-1838) first came down the Clearwater River far to the south in 1805, they wondered where all the Nez Perce had gone. They were told: They're up on the Spokane River, fishing. Other tribes came down from what is now Canada.

The fishing sites were not permanent camps. They were occupied only during the salmon season, from late July to September, when up to 5,000 people would gather to catch, smoke, and dry salmon for the long winter. The tribes trekked to these salmon camps even after the city of Spokane Falls was established in 1881. However, as the city grew and houses sprang up in Peaceful Valley, the gatherings dwindled.

Poverty Flats

A new identity for Peaceful Valley was slowly being forged -- one that would lead to one of its early names, Poverty Flat (or Flats). Peaceful Valley was right next to the burgeoning business district of Spokane Falls -- today's downtown Spokane -- yet it was separated by daunting physical barriers. A pedestrian walking west from downtown Spokane had to negotiate a switchback trail down a steep incline, or gully, to get to the pine-covered flat. This steep incline also separated Peaceful Valley from Browne's Addition, the swanky residential neighborhood just to the south. The way north was blocked by the broad, churning Spokane River, and the way west was obstructed by Hangman Creek and more steep hills. Peaceful Valley was, and remains, a small world of its own.

There were also legal obstacles to settling Peaceful Valley. Large portions were owned by the Northern Pacific Railroad as part of its land grant. The railroad held on to these parcels into the late 1880s. Other large tracts, including one known as Glover's Addition, was owned by James N. Glover (1837-1921), often called the father of Spokane, who then sold it to various other entities, including the Spokane and Inland Empire Railroad (Compau, 5). An 1884 aerial map of Spokane Falls showed no permanent structures in Peaceful Valley. Even after the railroads sold off their parcels, the steep approaches discouraged residential development. When streetcars arrived in Spokane in 1888, no tracks were built down those steep hills -- and never would be. An 1890 aerial map also showed nothing in Peaceful Valley except ponderosa pines. Another name for it at the time was Spring Flats, which suited its reputation as a serene place for Spokane residents to have a riverside picnic.

Poverty Flats became home to shacks and squatters, many of them. Despite the obstacles, the area was close to town and attractive to poor immigrants and itinerants. In 1891 the new owners of the Glover's Addition tract embarked on a campaign to clear out the shacks and lean-tos. That summer, the Spokane Falls Review ran this item, headlined "Clearing Poverty Flat":

"Poverty Flat, the district immediately below the falls upon the south bank of the river, which has been for some time inhabited by families in very humble circumstances, is being rapidly cleared of its former denizens and their families and restored to its primeval character. This work has been undertaken by ... the proprietors of the tract, and by the city board of health, who are soon to invoke the assistance of the scavenging department ... The families are scattering to all parts of the city in search of new homes" ("Clearing Poverty Flat").

From Poverty Flats to Peaceful Valley

Poverty Flat reverted to its so-called primeval character -- but not for long. In 1890 a large portion of the railroad land had been purchased by a pair of real-estate partners. One of them, C. F. Clough, platted the land into 25-foot-by-100-foot lots. By 1893 Clough had already sold a number of lots, but he needed to solve a serious marketing problem: the name Poverty Flats. On May 3, 1893, The Spokane Review (formerly the Spokane Falls Review) ran a story announcing "No More Poverty Flats." Clough "has rechristened the locality formerly known as Poverty Flats, Spring Flats, etc., to Peaceful Valley" ("No More Poverty Flats").

Clough borrowed the name from Peaceful Valley, an 1893 comedic play by Edward E. Kidder (1849-1927), set in the pastoral mountains of New Hampshire and starring actor Sol Smith Russell (1848-1902) as a young man working his way through college. It was enjoying a popular run in Chicago at the time, and Clough apparently believed it would create a more attractive image for his development. The new residents clearly did not want to be identified with the word poverty. "The new name is much more euphonious than the old, and will doubtless be readily accepted by those living in the locality, nearly all of whom own their homes and are an industrious, hard-working people," said The Spokane Review ("No More Poverty Flats").

However, the nationwide financial crisis known as the Panic of 1893 contributed to a Spokane real-estate slump, and only a few more homes were built in Peaceful Valley by 1900. But in the next decade development took off. Many of the homes were built by their owners and relatively modest. Nancy Gale Compau, in her definitive history of Peaceful Valley, wrote, "The houses were largely simple, wood frame workers' homes, one to two stories in height, built close together because of the narrow lots ... Decorative trim was often carved by the owners themselves ... Outbuildings included a shed and an outhouse; homeowners along the river frequently built their privies extending out over the water" (Compau, 9).

Even more modest were the "row cabins," which were "several small, one-room dwellings attached to each other, often under a single roof, which were rented to seasonal workers who came to winter in Spokane" (Compau, 10). By 1910 nearly every lot had a house, and there were even a few commercial buildings. The most significant was the Spokane Casket Company, which was built in 1901 at 1620 Water Street, near the eastern edge of Peaceful Valley. The owners brought in cedar from the Idaho panhandle and Canada to build simple wooden coffins and fancier upholstered caskets. It began with nine workers and later peaked at 45, and was an important economic engine for Peaceful Valley for almost 100 years.

Hard to Get To, Harder to Leave

Other local shops also sprang up, including a few grocery stores, butcher shops, barber shops, saloons, and laundries. These small neighborhood businesses were especially important, considering how difficult it was to climb the steep slopes out of Peaceful Valley into the commercial district of Spokane. The roads remained narrow, winding, and muddy. In 1897 residents had petitioned the city to build a road down the steep slope "wide enough for the passage of two teams" (Compau, 17), then raised money to match the city's share. The ensuing road, Main Avenue, passed under the south end of the old Monroe Street Bridge, but it remained steep and difficult. Eventually, when the modern, concrete Monroe Street Bridge was built in 1911, Main Avenue was given a more reasonable and gradual grade. Yet it was still a steep, two- or three-block slog up to Monroe Street and downtown.

Some of the "north-south streets were so steep they were labeled 'impassable for teams' and left in their natural state" (Compau, 18). In the original plat, the north-south streets were named after the Great Lakes (Huron, Michigan, and Ontario), but in 1909 were renamed Cedar, Maple, and Ash, to match the rest of the city's grid. In Bennett's Addition, the westernmost and more remote section of Peaceful Valley, many of the roads remained dirt trails until the 1930s.

Schoolchildren had to deal with a steep wooden stairway up to Washington School, which was in Browne's Addition. In 1915 one concerned mother told the Spokane School Board that this was "a hardship to small children" in Peaceful Valley ("School Addition ..."). She said one of her children had been "advised by the family physician not to climb the long flight of stairs" to Browne's Addition ("School Addition ..."). She and other mothers asked that Peaceful Valley be given its own school. The newspapers took up the cause, running photos of little children struggling uphill in the snow. In 1917 the school board finally built a two-room brick school at the corner of Clarke Avenue (the main east-west street) and Maple Street. It was called Cowley School, named after Spokane pioneer H. T. Cowley (1837-1917), who had recently died. The school opened in September 1917, housing only the first and second grades. Older children were still deemed hardy enough make the climb up to Washington School.

A Working-Class, Multi-Ethnic Enclave

Peaceful Valley was no longer Poverty Flats, but it was still one of the least affluent sections of town, and its character was decidedly working class. Occupations of Peaceful Valley men, as recorded in the 1910 city directory, leaned toward the construction trades, as well as millworkers, laborers, cooks, and teamsters. One early resident said that "a lot of loggers used to rent rooms all year around and come live here in the winter … you could get a room for five dollars … there was lots of bachelors" (Compau, 49) The women worked as seamstresses, laundresses, and domestic servants. A few made the trek up to Browne's Addition to work in the homes of Spokane's mining and logging magnates.

The ethnic makeup of Peaceful Valley reflected the burgeoning immigrant population of Spokane at the time: Germans, Swedes, Norwegians, Italians, and Irish. However, one ethnic community established a particular foothold in Peaceful Valley -- the Finns. From the beginning, Peaceful Valley attracted immigrants from Finland who had moved west for the region's logging and mining jobs. Many of these families found work in 1898 at a smelter in Northport, near the Canadian border, then moved to Peaceful Valley after those jobs vanished. A number of Finnish bachelors, mostly loggers, farmers, and miners, spent the off-season in small Peaceful Valley houses.

By 1910 the Finnish community was so robust that the Finnish Socialist Club of Spokane took up a collection to build the Finnish Social Hall in Peaceful Valley at 2022 West Clark Avenue. It was one of the largest structures in Peaceful Valley, a three-story frame building with a first-floor dance hall and stage, a basement kitchen facility, and a third-floor apartment for the caretaker. The hall hosted amateur plays, concerts, Christmas gatherings, athletic events, vaudeville acts, and community meetings.

The hall was the hub of the Finnish community, yet it also served as an informal community center for all of Peaceful Valley. It even was used as a political gathering place, sometimes for groups of a radical bent befitting its socialist roots. In 1917, when the Industrial Workers of the World (the Wobblies) called off a controversial wartime logging-camp strike, they did so at a mass meeting held at what the papers called "the Finlanders' hall" ("IWW Ends ..."). The Finnish Social Hall continued to be Peaceful Valley's main meeting place for decades.

Every Finnish community required steam baths, or saunas, and Peaceful Valley was no exception. Numerous wood-fired steam baths, usually rustic shacks made of wood, were built behind homes in Peaceful Valley. But there were also several commercial baths, including one in the basement of a home that included dressing rooms, showers, and separate steam rooms for men, women, and couples.

Glover Field

The most enduring public space in Peaceful Valley was Glover Field, also called Glover Stadium. In 1912 the Spokane Parks Board purchased a nearly three-acre site at Main Avenue and Wright Street for a stadium and athletic field. They built a football field, a six-lane running track, and bleachers seating 10,000 people. In 1917 it was formally dedicated as Glover Field in honor of James N. Glover ("Glover Field Is Dedicated ..."). This was particularly fitting since the land was part of his original Glover's Addition.

The field was heavily used by Lewis and Clark High School teams and those from other high schools, and also for grammar-school field days. One high-school track competitor recalled attending meets there and using the locker rooms under the bleachers. He said "they weren't very fancy and they leaked when it rained" (Compau, 23). In fact, the bleachers were condemned in 1925, although the field itself continued to be used heavily. The bleachers apparently survived, in dubious condition, until 1937, when the president of the annual Sportsman's Fair on the site said, "The old grandstands are too rotted to be of any use. They are now being dismantled" (Compau, 24).

Probably its most famous use was on October 30 and 31, 1925, when tribal members of the first Northwest Indian Congress pitched 88 tepees on Glover Field. This event was organized by Spokane civic leaders, partly as a way of creating a picturesque tourist draw. Nearly 1,000 Indians from 28 Northwest tribes attended. Glover Field was the main camping ground, mostly because of its proximity to the downtown meeting places, but also because of its history as the Indians' long-ago fishing site. The Spokane Daily Chronicle wrote that it evoked "pleasant memories of days long gone by as a gray dawn broke over the Indian tepee village" ("Indian Horde ..."). A second, even larger gathering, renamed the National Indian Congress, took place in 1926. But that was to be the final congress, as the tribes had come to the conclusion that the gatherings fulfilled no useful purpose.

A River Runs Through It

More than any other neighborhood in Spokane, Peaceful Valley's identity was shaped by the Spokane River. It was so close to the river that flooding became a problem during high-water years. Occasionally, homes had to be evacuated. In the early years, the river had a prominent rounded pool -- residents called it a bay -- at the westernmost end of Peaceful Valley. This was later filled in to ease the flooding problems.

For the most part, however, the Spokane River was the valley's playground. Some children growing up in Peaceful Valley thought nothing about swimming all the way across the rolling river to the north shore. "I swam that river a hundred times," said one resident. "I used to go over to see a girl over there. I'd have to go up quite a ways. There's quite a current" (Compau, 71). Most residents chose a somewhat drier option -- rowboats or canoes, which they tied up below their homes.

They also fished the river, with often spectacular results. "You haven't any idea the trout. I pulled 12-pounders under the Monroe Street bridge," said one old-timer (Compau, 58). However, the salmon that defined this spot for millennia were nowhere to be found. The salmon fishery ended forever after the big chinooks were blocked by the completion of three downstream Spokane River dams between 1908 and 1915: Nine Mile Dam, Little Falls Dam, and Long Lake Dam.

Depression and War

Peaceful Valley remained a quiet, working-class enclave throughout the 1930s and 1940s. During the Great Depression years, records showed "more widows, who were taking in boarders to make ends meet" (Compau, 34). Life -- and sanitation -- improved considerably in the 1930s when sewer lines were finally installed. No longer did Peaceful Valley rely on outhouses and privies built out over the river. Cowley School closed in 1930 due to a shortage of funds and a dwindling student population, so children resumed the long climb to Washington School. Glover Field enjoyed a resurgence as the location of a training camp for professional boxers, including a light-heavyweight champion with the colorful name Slapsie Maxie Rosenbloom (1906-1976).

The Finnish character of Peaceful Valley had become diluted, and in 1942, the Finnish Social Hall was torn down after sitting vacant for several years. "The club faded from the picture when many Finns enlisted in the First World War," noted The Spokesman-Review ("Finns' Old Hall ...").

The World War II years brought an increased demand for inexpensive housing as workers flocked to Spokane's military installations and aluminum plants. Many of the old houses were converted to apartments. Real-estate investors bought up other houses. According to Compau, this began the "cycle of absentee ownership which would plague the Valley for many years to come" (Compau, 35).

A Baleful Bridge

The most profound change in Peaceful Valley occurred in 1957, when the massive Maple Street Bridge was built high overhead and straight through the center of Peaceful Valley. Several blocks of homes were demolished to accommodate the bridge's massive piers. "Heartsick homeowners, who had lived most of their lives there, saw their homes torn down," wrote Compau. "The empty land left underneath the bridge became a barren, refuse-filled dust bowl. The shadow of the bridge obscured the sun and a steady rain of debris showered down on it, dirtying yards and killing plants and shrubs" (Compau, 36). The bitterness has lingered for decades. In 2014, one longtime resident wrote, "Put a bridge over us and hoped we'd leave ... We stayed in spite of the movers and shakers, we are still here" ("The Unique Character ...").

Peaceful Valley's community bonds continued to hold, helped in large part by the establishment of a recreation center at the east end of Glover Field, paid for by the Junior League of Spokane. It was a former barracks building, bought and moved from nearby Geiger Field in 1949. It opened in 1950 after the Junior League and the city parks department completely renovated the building and added a softball diamond and playground. It fulfilled the role of the old Finnish Social Hall and more, hosting art classes, cooking classes, gym classes, games, movies, and dances. When Peaceful Valley was designated a Community Development neighborhood in 1976, and thus eligible for federal urban renewal funds, the recreation center was expanded, renovated, and turned into the Peaceful Valley Community Center. Today, it remains Peaceful Valley's social and cultural hub.

A Bohemian Enclave

In the 1960s and 1970s, Peaceful Valley gained a reputation as a counterculture enclave, partly because of its low rents, but also because of its reputation as a haven for iconoclasts and political mavericks, which lingered from the old Wobbly days. In 1972 a group of young Spokane radicals formed a chapter of the Youth International Party -- famous as the Yippies -- and opened their ramshackle office in Peaceful Valley, across from the Spokane Casket Co. It "cost us $20 a month to rent," said one of the founders (Youngs, 298). They used the office to publish their newsletter and organize. Later they would hold their own "counter-fair" to Spokane's World's Fair, Expo '74, on the far western side of Peaceful Valley at a place they called People's Park.

Peaceful Valley developed a reputation as an inexpensive haven for artists and musicians. One longtime resident called it a "low-key, unpretentious atmosphere ... classical pianist next to a Clint Black [country music] fan" ("The Unique Character ..."). Peaceful Valley even enjoyed a brief fling of Hollywood fame in 1992 when many scenes in Benny & Joon, starring Johnny Depp (b. 1964), Mary Stuart Masterson (b. 1966), and Aidan Quinn (b. 1959), were filmed there. The home of the two title characters was on the corner of Water Avenue and Cedar Street, a house chosen partly because of its location right on the Spokane River, with the Maple Street bridge looming overhead. A review in The Washington Post said the movie was set in "a fairy-tale section of Spokane" ("Benny & Joon").

In recent decades a few luxurious homes have replaced some of the historic homes on the river. Some modern townhomes have sprung up. Directly across the river from Peaceful Valley looms one of Spokane's fastest-growing urban housing developments, Kendall Yards. However, the same circumstances that kept it a hidden enclave from the beginning -- the steep slopes and the broad river -- have allowed Peaceful Valley to retain a large part of its historic look and character. In 1984, it was designated as a National Register Historic District.

The salmon no longer run, the Finnish Social Hall is long gone, and the Spokane Casket Company ended its long run when the building was demolished in 2000. The Cowley School no longer holds classes, but the Cowley School building still exists and has been made into apartments. Glover Field still hosts softball games. Children still climb the stairs up to Riverside Avenue. Meanwhile, the Spokane River rolls quietly past houses built by Finnish carpenters.