The Lynden Tribune was first published in 1908, but its real beginning dates to 1914, when Sol Lewis (1888-1953) published his first edition of the paper he had just purchased. Lewis, a down-home writer who loved his job as a self-described country editor, built the paper into a well-respected weekly that eventually became known throughout much of Washington and, to some extent, the country. In 1953 he was succeeded by his sons Bill (1920-2011) and Julian (1926-2005), who successfully managed the Tribune for much of the remaining twentieth century. The brothers also established the Lewis Publishing Company, which has since published a number of Whatcom County newspapers, historical books about Lynden, and more. Sol's grandson Michael Lewis (b. 1957) became publisher of the Tribune in 1992. He has continued to expand its footprint in the quarter-century since, including adding the Lynden Print Company in 2011 to better handle the Tribune's publishing operations.

Early Incarnations

Although the Lynden Tribune's first issue was published on July 9, 1908, the city's newspaper roots date two decades back, to October 16, 1888, when the Lynden Pioneer Press debuted. The paper, produced in a wooden building on the south side of Front Street at 4th Street, was owned by Wesley H. Dobbs. L. D. Pangborn was the editor, and much to his delight the little paper grew along with Lynden, which had only begun to coalesce into a village in the preceding few years. He wasted no time bragging of the paper's success, crowing in a January 1889 editorial, "It has succeeded thus far beyond the most sanguine expectations of its proprietor and friends" (Koert, 30).

The Pioneer Press remained in operation until 1900, and a brief paperless hiatus followed in Lynden. The Pacific Pilot, published by W. H. Towner, was established in August 1901 and published for nearly three years. The Pilot was a well-written and informative paper and makes interesting reading about the happenings of the day, both major and minor, in early twentieth-century Lynden. In 1904 the Lynden Sun followed as Lynden's third newspaper, but it lasted little more than a year before it was replaced by the Lynden Sun-Pilot. Three years later, the Sun-Pilot was sold.

The new owners named the paper the Lynden Tribune, and its first issue appeared on July 9, 1908. The paper's masthead shows Charles D. Jones as editor and H. E. Stuart as business manager. In 1909 Dan Cloud (a former editor of the Tacoma Daily News) bought the paper, but he sold it in 1911 to Herman Rosenzweig, who ran it for three years before selling it to a young journalist named Sol Lewis.

Sage of the Crossroads

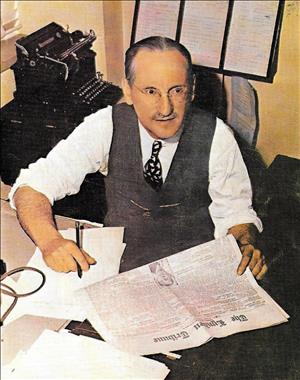

Lewis was a 1912 journalism graduate of the University of Washington. In the two years since graduation he'd had a full plate, working as a reporter on the New York World and teaching at both the University of Kansas and the University of California at Berkeley before coming to Lynden in the autumn of 1914. His entry into the Lynden community with his first issue, on October 22, 1914, was as low key as could be. While Rosenzweig had written a goodbye a week earlier, Lewis wrote no greeting, and there was no announcement in the paper of his purchase. The only difference was on the masthead, where Rosenzweig's name was replaced by Lewis's. This soon changed, and the name Sol Lewis -- and two generations of the Lewis family after him -- went on to become synonymous with the Lynden Tribune.

Sol Lewis was a bright, articulate, witty writer who quickly fell in love with the little community that he nicknamed Parsnip Corners, and his affection shows in his writing. His folksy, Will Rogers-like style resonated with his readers. In 1917 he began his column, The Lynden Gimlet (named after a tool used to bore holes, not the drink), which featured comments and humor about life in Lynden. He wrote the popular column into the 1950s, though in his later years it was frequently substituted with Gimlet Gems, a highlight of columns from 10, 20, and 30 years earlier.

Here's a Gimlet example from 1922:

"Lynden now has four more citizens with jail records. The desperate characters are George Abbott, Lawrence Asam, Joseph Shoop and Carl Boice. They were incarcerated in the county calaboose for an hour, charged with holding a dip-net in the crystal waters of the Nooksack. The quartet pleaded 'not guilty' and intend to fight it out in the courts even if they have to appeal to the League of Nations" (The Lynden Gimlet, December 28, 1922).

National Notice

Lewis sang the praises of small-town life every chance he got. As he told American Magazine in 1920, "I wish to goodness I could persuade more newspaper men to drop their puny, scrambling jobs in feverish city offices and get double the pay and triple the happiness in the country field … do you know many city newspapermen who are absolutely independent, who write what they think, or do as they please? I do" ("About Us"). He received any number of offers for bigger jobs in bigger cities but turned nearly all of them down, even after he catapulted to national fame in a 1942 radio broadcast of America's Town Meeting of the Air, a popular weekly radio show that featured discussions of current events by noted newsmakers.

The broadcast, aired from Meany Hall at the University of Washington in Seattle on August 6, 1942, featured publishers of various newspapers, both large and small, discussing the role of the press during wartime in the midst of World War II. Lewis, representing the small weekly newspaper, knocked the ball out of the park with his simple, optimistic, damn-the-torpedoes philosophy. He became something of a national sensation overnight. Letters and telegrams poured into the Tribune office, some requesting subscriptions to the paper, others containing job offers. Lewis happily filled the subscriptions and just as happily turned down most of the job offers.

There were two offers he did take. He accepted an offer to write a column for The Seattle Times, a gig that lasted more than eight years and brought him even further renown. He also accepted an offer to host a weekly 15-minute radio show that was broadcast over most of the state, in which he provided a grassroots perspective of the happenings of the day. A review of radio listings from 1942 and 1943 indicates that the show was on the air for a little less than a year.

New Content, New Styles

Lewis's death from a heart attack on June 12, 1953, came as a shock, though those who knew him knew he'd also been battling diabetes. The community -- not to mention countless fellow writers and editors -- mourned the loss, but it was hardly the end of the Lynden Tribune. Writing and publishing run in the Lewis family. Sol Lewis's wife, Aimee (1896-1972), was a syndicated home-economics columnist in 14 West Coast weekly papers (including the Tribune), and his two sons, Bill and Julian, were both journalism graduates of the University of Washington. Bill joined the Tribune in 1945 and Julian in 1948, so they were not unprepared to take the reins. Bill handled more of the paper's writing and editing operations, while Julian took care of the publishing and business operations. But Julian -- known as Judge to his family and friends -- was also a writer, and he wrote a sports column for years titled Judge's Verdicts.

Julian Lewis also expanded the paper's commercial printing business. Incorporation papers for the Lewis Publishing Company were filed with the Secretary of State's office in 1959, and it grew from there. Within 25 years the company had become an integral part of the Tribune. By the 1980s it printed many of the area's school newspapers, and it also published two other area newspapers, the Point Roberts Ocean Star and the Skagit Farmer. Later this grew to include the Ferndale Record and Whatcom Extra. The company also published a number of historical books about Lynden penned by local writers.

The Tribune's content changed to meet the changing times. In addition to more sports coverage, more pictures began appearing in the paper. Stories became more in-depth, and more stories written by women began appearing in the paper. Bill Lewis's wife, Margaret (1923-2014), wrote columns on travel, food, and real estate for the Tribune (as well as at least one humorous article for a boating magazine, discussing the perils of boating with her husband). Their daughter Marilyn (b. 1948) worked at the Tribune as a reporter and photographer for three years in the late 1970s and early 1980s before moving on to work for larger papers, and during her years at the paper she was part of an award-winning, all-female staff that included Heidi Henken and Carolyn Price.

The Tribune's style also changed to some extent, although it remained the same small-town, conservative newspaper it had always been. Bill Lewis continued The Lynden Gimlet into the 1960s, but in 1961 he began his own editorial column, which he named At Deadline. (In it, he called himself the Deadline Breaker.) However, his style was entirely different from his father's. Sol Lewis was not one for confrontation, preferring instead to point out the issues of the day with humorous quips. Bill Lewis was more aggressive. Though equally as big a Lynden booster as his father had been, he had no problem calling out its leaders in ways his father would never have. "I enjoy controversy," he admitted when he was interviewed by the Bellingham Herald upon his 1984 retirement (… at Deadline, 128)

Lewis found controversy aplenty with his 1981 editorial, "The Holy City," when he wrote a scathing editorial slamming the city council's hasty passage of an ordinance banning dancing in the city's bars. The ordinance (still in effect in 2017, with little notice) attracted attention all over the country, with lots of snickering press coverage. Even The Wall Street Journal weighed in with a humorous article that included an interview with a local attorney who claimed that Lynden was the only town in the country with such a ban. But Lewis wasn't particularly concerned with the ban itself. "It's a moral issue for some people and I respect that," he explained in the Herald interview. "I differed with the way the ordinance banning dancing was drafted. The city attorney wouldn't release a copy of the ordinance before the city council meeting. I felt freedom of information was being stifled" (…at Deadline, 128).

Many shared Lewis's view. Nevertheless, Lynden, a deeply devout community, erupted when his editorial came out. Some readers dropped their subscriptions, and at least one advertiser withdrew his business. Letters both pro and con flowed into the Tribune's office. The brouhaha split the community, and tongues wagged for months. Lewis told The Wall Street Journal that it was the bitterest fight he'd seen in 60 years in Lynden. He stood his ground, though he later conceded he could have chosen some of his words better. The debate lingered as challenges to the ordinance dragged through the judicial process before an appeal was summarily dismissed by the Washington Supreme Court in 1984.

Bill Lewis retired in 1984 (though he kept writing his At Deadline column into the twenty-first century) and Julian Lewis retired in 1991, but by this time a third generation of Lewises was established at the Tribune. Julian's son, Michael, joined the Tribune in 1980 after he graduated from Washington State University, and became a co-publisher with his father when Bill Lewis retired. In January 1992 he became publisher of the Tribune, later joined by his wife, Mary Jo, as co-publisher.

The Lynden Tribune Today

Michael Lewis has had his own challenges since joining the Tribune. Between 1980 and 2017 Lynden's population more than tripled, with most of the growth taking place since he became publisher in 1992. A bigger population base expects more from its local paper, and the Tribune has responded by expanding its reporting to include special features. In 2017 these features included home and garden, a health-care guide, and the paper's annual tribute to the renowned Northwest Washington Fair. The Tribune completed a major upgrade to many of its computer systems in the mid-1990s, just in time to meet the Internet and the opportunities and challenges it presented when the Tribune began publishing online. Under Michael Lewis's management the paper's publishing operations have also continued to expand, and in 2011 the Lynden Print Company was incorporated to better handle these. The company offers a wide range of products and services, not only for writers and publishers, but also for the area's businesses and churches.

The Tribune was a Front Street fixture for much of the twentieth century -- hence the title of Bill Lewis's 1991 book ... at Deadline -- "70 Years on Front Street," in which he shares stories and columns from his life and times in Lynden and at the Tribune. Beginning in 1915 the Tribune was located in the Wood Building at 523 Front Street, an easy walk for Sol Lewis from the family home at 107 Front Street. The paper moved to a larger building at 610 Front Street in 1939, and in 1980 moved to its present location at 113 6th Street.

Throughout its history the Lynden Tribune has been a weekly, publishing on Thursdays until the 1970s, then switching to Wednesday. For more than a century it has been a consistent voice for northern Whatcom County, and both the paper and its writers have won numerous awards through the years. The Tribune has in turn given back to the community in a myriad of ways. Two civic activities that it sponsors every year are the Readers Care Fund, which since 2006 has raised more than $130,000 for two local food banks, and the Sol H. Lewis Award, a more well-known sponsorship established in 1981. The Sol Lewis Award -- actually two awards -- recognizes a local man and a woman who have gone the extra mile to improve their community. This includes not just Lynden but also the surrounding communities within the Tribune's primary circulation area, stretching south from the Canadian border almost to Bellingham, and east beyond Deming and Sumas. The paper's seemingly small circulation figure of 5,000 is deceiving, because its reach in Lynden and its environs, both historical and contemporary, extends considerably beyond that of any typical small-town paper.