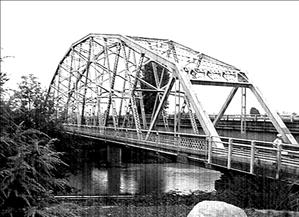

The Meridian Street Bridge over the Puyallup River in eastern Pierce County was built in 1925 to shorten the traveling distance between the Puyallup Valley and points north, particularly Tacoma to the northwest. A riveted, steel-frame span based on the popular Warren through-truss design, it was modified in a manner that made it perhaps unique. The bridge remained unchanged until 1951, when new approaches were constructed. In 1971 it became northbound only, and in 1991 the overhead structures at both portals were altered to accommodate larger commercial vehicles. By 2011 time and the elements had taken their toll, and the span's deteriorating condition required load restrictions. In late 2013 a contract was let for design and construction of a replacement, and in July 2014 the old bridge was moved east approximately 60 feet, where it continued to handle northbound traffic while the new span was built. In 2015 the Meridian Street Bridge was moved intact to storage in the hope that it could be donated and repurposed, perhaps for use on a pedestrian or bicycle trail at a different location. As of July 2017 there had been no takers, but the offer was to remain open until summer 2019.

Connecting the Valley

Southeast of Tacoma the Puyallup River flows through the Puyallup Valley, the ancestral home of the Puyallup Tribe of Indians, whose name in their aboriginal language means "generous and welcoming behavior to all people (friends and strangers) who enter our lands" ("Puyallup Tribal History"). This benevolent ethos proved of little benefit when the first non-Native settlers appeared in the valley in the early 1850s. Such newcomers were appropriating Indian land across Washington Territory to their own purposes, actions soon ratified by unfair treaties the tribes had little choice but to sign. Justifiable Native anger led to the Indian Wars of 1855-1856, and some members of the Puyallup Tribe joined in as combatants. Almost all non-Native settlers in the valley fled their homesteads in fear, and the first to return did not do so until 1859.

When the settlers did trickle back, the rich alluvial soil of the valley enabled many to prosper. Within a decade, subsistence farming was being replaced by huge harvests of hops, a flavoring ingredient of beer that was in demand everywhere beer was made, or just about everywhere on Earth. For the next 20 years and until an infestation of hop lice destroyed the crop in 1891, the valley was one of the world's foremost hop-growing areas, and several fortunes were made. When the hops fell victim to insect infestation, berries and eventually flowers became the valley's primary cash crops.

One of those who prospered greatly from hops was Ezra Meeker (1830-1928). In 1877 he platted 20 acres of his hop farm to create the town of Puyallup, and in 1890 Puyallup's 1,500 citizens voted to formally incorporate the town. By the turn of the century, poultry and dairy farms had appeared in the valley, along with sawmills and woodworking plants. But it was berries -- blackberries, raspberries, strawberries, loganberries, and gooseberries -- that remained the most lucrative cash crops.

Somewhat unexpectedly, Puyallup's next boom came not from agriculture but from automobiles. In 1912 the Pierce County Auto Company opened in the town to sell Ford automobiles. It was a roaring success, and Puyallup soon became known as the best place in the region to buy a car. What were now needed were better routes not only to get the valley's agricultural products out, but also to bring potential car buyers in. Part of the solution would be a new Puyallup arterial -- Meridian Street -- and a bridge to carry it across the Puyallup River.

The Engineer

In November 1924 Pierce County applied for federal aid to build a "steel highway bridge crossing Puyallup River" (Holstine, 4). The bridge was one component of a new route that would shorten the distance and time to travel from the town of Puyallup and surrounding rural areas to points north, particularly Tacoma, across the river and about five miles away to the northwest. The other component of the project was a new road, to be called Meridian Street, which would connect to the bridge on the north and south banks of the river. Meridian Street and the bridge would eventually become part of State Route 167.

Although unremarked at the time, the design of the Meridian Street Bridge was not only innovative but appears to have been unique among bridges in North America and perhaps worldwide. It combined elements of at least two existing truss-span designs, one very common and one very rare, but differed in varying degrees from both. While his name did not appear on the initial drawings submitted in support of the request for federal aid, the design of the bridge was clearly the work of Maury M. Caldwell (1875-1942), an independent consulting engineer with offices in Seattle's Central Building.

Caldwell had long experience in bridge design, having previously worked for the C. G. Huber Company, the Union Bridge Company, and the Strauss Bascule Bridge Company. He is believed to have arrived in Seattle in 1904 from Virginia and soon was working as a draftsman in Tacoma's City Engineering Department. In 1910 he became a named partner in an engineering firm, then returned to government employment and by 1914 was the chief deputy engineer for Pierce County, living in Tacoma. By 1916 he had married and returned to private practice.

Two bridges in Washington that Caldwell is believed to have designed before the Meridian Street Bridge were the steel, deck-truss Burnett Bridge, built in 1920 to cross South Prairie Creek in Pierce County and, in 1922, the Pasco-Kennewick Bridge, a 1,410-foot span that was the first of three cantilever bridges built across the Columbia River in the 1920s. In 1921 he supervised the construction of, and may have had a hand in designing, the James O'Farrell Bridge in eastern Pierce County on SR 165, a spectacular deck-arch span that crosses high over the Carbon River.

After the Meridian Street Bridge was completed, Caldwell designed or supervised the construction of at least two more bridges in Washington. He died in 1942 while at work developing a gold mine in British Columbia. Interestingly, there is no record of Caldwell ever being licensed as a professional engineer in Washington, but those were simpler times, and his expertise seems not to have been in question.

The Bridge's Basics

It is difficult to discuss the structural specifics of bridges without using the jargon of those who design and build them, and the illustrations accompanying this essay may be useful in understanding this terminology. At its most basic level, the Meridian Street Bridge is a modified (or subdivided) Warren through-truss span. The Warren truss design was first patented in England in the mid-nineteenth century and was one of the simplest and most common designs for bridges comprised of riveted or bolted steel members. A through-truss bridge is one in which the two vertical sides are connected at the top by a webbing of transverse steel cross-members, which strengthens the structure but limits vertical clearance for vehicles. Bridges without this cross bracing are known as pony trusses and have no such height limitations, but are less robust when subjected to heavy loads.

A standard Warren truss has parallel horizontal top and bottom chords (the longitudinal members that run the length of the bridge) and diagonal steel beams that connect them on either side. These form the vertical truss structure of the bridge and form a series of equilateral triangles in a zigzag pattern along the length of the span, bearing the forces of both compression (squeezing together) and tension (pulling apart). The Meridian Street Bridge was designed with 13 alternating triangular sections on either truss, although as explained below, not all were equilateral. Warren truss bridges are relatively light and strong, but without additional supporting structures are not suitable for longer spans.

A Unique Design

Caldwell's design for the Meridian Street Bridge differed from the pure Warren form in several respects, as described by the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT):

"Unlike the standard Warren truss, this bridge has parabolic top chords (allowing for a longer span length), alternating diagonal truss members, longitudinal braces between diagonals in alternating panels, and vertical struts adjacent to the portals. Its subdivided panels and the addition of longitudinal members at mid-panel heights in five truss panels achieved both strength and economy of steel" ("For Sale: ...").

The most visually obvious variation from the standard Warren truss was the use of parabolic top chords. Rather than being continuous horizontal members running parallel to the roadway, in the design for the the Meridian Street Bridge the top chords are made up of angled segments that rise gradually from either end and meet at the middle, forming a parabolic arch that adds considerable strength but little weight to the entire structure. Because the top chords are not parallel to the bottom chords, every second triangle (the ones for which the base is formed by the top chord) is not equilateral, unlike a standard Warren truss. In this respect, the profile of Caldwell's design resembled a Pennsylvania truss, named after its originator, the Pennsylvania Railroad.

The above mention of "alternating diagonal truss members" and "longitudinal braces between diagonals" is best understood through the drawings and photographs. Suffice it to say that the reference is to additional supporting members that are connected to and subdivide the basic Warren truss configuration, adding strength and rigidity.

A Possible Influence

Although there is no way to be certain, it appears that Caldwell's 1924 concept for the Meridian Street Bridge may have been influenced by a design patented one year earlier by Claude Allen Porter Turner (1869-1955), a structural engineer who worked out of Minneapolis. Turner's design was intended specifically for long bridges, a category that the Meridian Street Bridge did not really fit into. It seems that only one span, finished in 1922, a year before Turner applied for his patent, was ever built to this specific design. This was the Liberty Memorial Bridge that crossed the Missouri River and linked Burleigh and Morton counties in North Dakota. In January 1923, before filing his patent, Turner published the details of the bridge's design in an engineering journal, which was certainly accessible to Caldwell. Comprising three linked 479-foot spans, the Liberty Memorial Bridge was, so far as is known, one of a kind. Nonetheless it was demolished in 2008, much to the dismay of bridge historians.

The primary difference between the Turner and Caldwell designs is somewhat more subtle than their mutual departures from the standard Warren truss form. Turner's design included vertical supports at regular intervals along the entire length of the span. Caldwell's design for the Meridian Street Bridge, by contrast, only had "vertical struts adjacent to the portals" at either end of the bridge ("For Sale: ..."). In his patent application, Turner drew the additional vertical supports as dotted lines, indicating that they may have been considered optional, but on the completed Liberty Memorial Bridge they were all present. There are one or two other minor variations between the Turner and Caldwell designs that defy description in words and are best understood from the comparative drawings.

At the time of its decommissioning in 2015 the Meridian Street Bridge was "the longest ... riveted steel Warren through truss span built prior to 1940 remaining on the Washington State highway system" (Holstine, 2). It seems undisputed that its precise configuration is unique among bridges in North America, and to date no other bridge of identical design has been found anywhere in the world. For this reason WSDOT has taken rather extraordinary steps to preserve it, more fully described below, although as of 2017 its fate remained uncertain.

Building the Bridge

In February 1925 Pierce County awarded the construction contract for the Meridian Street Bridge to the Puget Sound Bridge & Dredging Company of Seattle, which had entered a bid of $77,200, the lowest of the 10 that were received. The promise of the project, which included the new Meridian Street as well as the bridge, was outlined in a local newspaper, later quoted by WSDOT: "The new road [Meridian Street] will considerably shorten by the northern route, the distance to Tacoma and will also bring the big [Puyallup Indian] Reservation district a mile closer to Puyallup" ("Project Overview").

Construction began in early March of 1925, and building the bridge proceeded more smoothly than that of the street that was to cross it. Information compiled by Craig Holstine of WSDOT for the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation (DAHP) tracked the progress through reports published at the time in the Puyallup Valley Tribune or contained in the Meridian Street Bridge file of the Pierce County Department of Public Works:

"Piling and falsework had been erected across the river by mid May when the same newspaper reported that construction was ahead of schedule on the bridge, but that Meridian Street 'is not in condition, nor have any definite steps been taken toward improvement or paving.' Concrete piers were 'virtually' complete when 380 tons of steel from the Virginia Bridge and Iron Company in Roanoke, Virginia, arrived on site the next month. On July 4th C. J. Flem, superintendent of construction for the Company, reported that riveters had started work on the steel in place across the river, and that the 5 ½-inch-thick concrete deck was 'virtually completed.' The bridge was finished in time for the opening of the Western Washington State Fair [known as the Puyallup Fair until 2012] on 21 September 1925, but Meridian Street remained unpaved, due to refusal by the City Council to fund improvements. Finally County Commissioner Henry Ball had the street 'put in shape' for Fair traffic, despite the Council's recalcitrance" (Holstine, 5, internal citations omitted).

The report also notes, "In October, work commenced near the bridge on the pyramidal concrete and stone marker with bronze plaque commemorating the first road or Indian trail across the river at the site, the first school in the Puyallup Valley housed in the Indian War blockhouse that stood 'Near the north approach,' and the first telegraph line to reach the community" (Holstine, 5). The bridge indeed was on historic ground.

The steel-truss span when completed was 371 feet long, with a roadway width of 21 feet, nine inches (adequate for its day) and an eight-foot-wide wooden sidewalk running along the length of the span's east, or upstream, side. In 1951 a 21-foot-long precast, prestressed girder span and two 19-foot-long timber trestles replaced the original timber approaches on the south end of the bridge, together with two new 19-foot-long timber trestles on the north side. The total length of the bridge and its approaches was then 468 feet.

The ends of the steel truss span rested on dumbbell-shaped, reinforced-concrete piers that rested on timber piles driven deep into the soil near the banks of the river. In addition to the 1951 replacement of the bridge's approaches, in 1991 the overhead structure of the portal at either end was modified to increase vehicle clearance by four feet. At some point, 21-inch-high metal thrie beams (guardrails) were attached to the inside (traffic side) of the trusses, reducing the roadway width to an even 21 feet.

In one of those happy occurrences that give perspective to the state's relatively short history, Ezra Meeker, who with his wife and infant child had traversed the Oregon Trail by oxcart in 1852, settled in the Puyallup Valley a decade later, and platted the town of Puyallup 15 years after that, lived long enough to cross the Meridian Street Bridge shortly after it was completed in 1925.

Worn Out

Caldwell's unique design for the Meridian Street Bridge proved durable, and the span served for nearly 90 years with only regular maintenance and the few modifications noted above. For its first 46 years, the bridge carried traffic across the Puyallup River in both directions; in 1971 a new concrete span was built immediately adjacent to the old bridge's west truss to carry southbound traffic, and both lanes of the old bridge were dedicated to use by northbound vehicles. The new bridge was a bit of a visual blight, as it loomed several feet above the roadway of the older span.

In January 1991 deterioration of the Meridian Street Bridge's floor beams led to the imposition of load limits requiring that vehicles heavier than five tons use the right lane only. A study in 2012 noted "the steel members are exhibiting severe corrosion and the concrete deck and piers are delaminating" and "the width of the bridge does not meet current standards for lane and shoulder widths, which is problematic due to the high volume of truck traffic that utilizes the bridge" ("Puyallup River Bridge Preservation Strategy," 2).

Although the Meridian Street Bridge was listed in the Historic American Engineering Record's inventory of Washington bridges, compiled in 1979, in 1980 it was deemed not eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places. Similar findings of non-eligibility were made in 2000, 2003, and 2006. But in 2011 the Washington State Department of Transportation took another look and determined that the bridge did indeed meet the criteria for listing. The Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation concurred, and the determination was reaffirmed in 2014.

However, the Meridian Street Bridge had by this time been found to be both functionally obsolete and structurally deficient. It could not be preserved in place and could not bear vehicle traffic for much longer, but it had not yet quite finished its service. After some deliberation, it was decided that the most efficient way to proceed with the least disruption to traffic would be to move the Meridian Street Bridge 60 feet to the east, where new temporary approaches were constructed. It could then continue to carry northbound traffic across the Puyallup River until a replacement span was completed at its former location.

Between July 11 and July 13, 2014, laboring night and day, workers demolished the old approaches, lifted the bridge onto dollies running on tracks, moved the entire structure intact 60 feet to the east, and connected it to the temporary approaches. The gap that was created between it and the 1971 span became the location of the new bridge, which was completed in late June 2015.

Moving the Bridge

When the new bridge opened in 2015, the original Meridian Street Bridge was no longer needed and was in fact in the way. But its historic nature and unique design had earlier persuaded WSDOT and DAHP that extraordinary measures to preserve it should be taken. Relocating and repurposing it in its original configuration was thought feasible, and one proposal that surfaced in 2012 was to use the span to carry pedestrians across the White River on the Foothills Trail between Enumclaw and Buckley. In the meantime, the Meridian Street Bridge, intact save for its pavement, would be moved to storage on an unused state-owned right-of-way not far from the original site.

Moving a 371-foot-long, 378-ton riveted-girder span 60 feel laterally was challenging enough, but moving it a quarter mile down a two-lane public highway was another matter altogether. Beginning on Friday, August 7, 2016, crews from Omega Morgan, a company specializing in complex moves, raised the old span 21 feet in the air using hydraulic jacks, then slid it sideways 60 feet to the west onto 24 dollies that were parked on the recently completed new bridge. Each dolly rode on eight heavy tires in two rows of four each.

Once the Meridian Street Bridge was safely set on the dollies, a huge Kenworth prime mover tractor unit, connected to a short trailer heavily ballasted with concrete blocks, was attached to a front transverse deck beam of the span. Ever so slowly, it pulled the entire bridge north down SR 167 (N Meridian Avenue), across the southbound lanes of SR 167, and onto a vacant WSDOT right-of-way to the west of the road. Videos of the move are available on YouTube, the links provided in the sources below.

An Uncertain Fate

Unfortunately, it proved financially unfeasible to repurpose the Meridian Street Bridge for use across the White River on the Foothills Trail, despite generous terms offered by WSDOT. Although the bridge is characterized as being "For Sale," it would actually be donated to a qualified governmental or private entity for repurposing, together with one million dollars, the amount the department estimates it would cost to demolish the structure ("For Sale: ..."). Any taker would have to agree to two primary conditions: to maintain the bridge and the features that give it its historic significance, and to assume all future legal and financial responsibility for the span, including providing an agreement to hold WSDOT harmless in any liability action.

Even with a million dollars of state money, disassembling, moving, refurbishing, and reassembling the bridge at another location would be a considerable logistic and financial undertaking. As of July 2017, the state had received no qualified proposals. WSDOT committed to keeping the Meridian Street Bridge intact at its present location until June 2019. If arrangements were not made by then for moving and repurposing the historic span, plans called for it to be demolished and the steel recycled, an undignified end to the long and useful life of a bridge that is in all likelihood one of a kind.