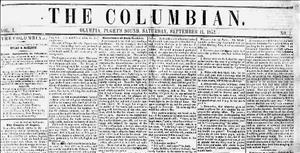

On September 11, 1852, The Columbian, Washington's first newspaper, is published in Olympia. Washington is not yet a territory, much less a state, and Olympia is identified in the paper's front-page banner as "Olympia, Puget's Sound." The scrappy little paper will champion the creation of a new territory north and west of the Columbia River, and will more than succeed when an even larger territory than it advocated for is established in 1853. Under several editors with varying personalities, the paper lasts for a little more than a year. But the already-old Ramage press it's printed on will serve several more preeminent pioneer papers, becoming an Energizer Bunny of printing with its own remarkable history.

Beginnings

Congress created Oregon Territory in 1848, which included what later became Washington Territory and eventually Washington state. Within a few short years the relative handful of non-Natives (nearly all of them men) living in the northern reaches were calling for a separate territory to be created north and west of the Columbia River. In August 1851 approximately two dozen men met at Cowlitz Landing (near present-day Toledo, Washington), drafted a proposal for a new territory, to be named Columbia, and sent it to Oregon Territory's Congressional representative, Joseph Lane (1801-1881). Lane filed it with the clerk of the committee on territories, but no further action was taken.

The northern settlers were frustrated by the distance between what was then called Northern Oregon and the territorial capital at Salem and were concerned that their interests were being ignored. Some continued to push for the creation of a new territory, but support was tepid. Part of the problem was that the territory north of the Columbia was still so sparsely populated by non-Natives. What few were there were more interested in surviving than politicking. Proponents for a new territory were worried that if they didn't keep pushing, the area would soon be accepted by all as Oregon Territory.

Thomas Dryer (1808-1879), editor of Portland's Weekly Oregonian and a supporter of the proposed territory, decided to keep up the pressure for the cause by establishing a newspaper in Olympia, an up-and-coming town north of the Columbia River. In 1852 he sent two of his employees, James Wiley (ca. 1820-1860) and Thornton McElroy (1825-1885), to the frontier community. It took the two men nearly seven months to set up shop in a one-story cabin at the corner of 2nd and Washington streets, in part because they had trouble finding the type fonts needed to print a paper.

Wiley and McElroy were total opposites, a journalistic odd couple who never clicked personally but managed to work together well enough to put together a good newspaper. Wiley, the editor, was a good writer but a party animal, a wild-looking, hard-drinking Irishman who enjoyed boasting that he "couldn't write until he got so drunk he couldn't walk" (Strong). McElroy, five years Wiley's junior, was quieter, neater looking, and a churchgoing man who pined for the wife he'd left behind in Illinois when he'd immigrated to the Oregon Territory in 1849. But he was no shrinking violet. Described as "two-fisted and strong-willed" (Strong), McElroy became the paper's publisher and business manager.

Vol. 1, No. 1

The first issue of The Columbian came out on Saturday, September 11, 1852, printed on a hand-cranked, wooden-frame Ramage press small enough to fit inside a grand piano box. At its best, the press could only print about 60 to 70 papers an hour, but this wasn't a problem: Olympia's population in 1852 was less than 300, while the population of the proposed territory itself numbered no more than a few thousand.

The paper was a four-page weekly, and a mostly legible copy of that first edition survives today. The front page reprints an essay from the National Intelligencer (Washington, D.C.) about the "Empire of Japan," and includes a few friendly tips, including one warning readers against "rush[ing] into matrimony totally unprepared for the awful change that awaits them" (The Columbian, September 11, 1852, p. 1). A similar cautionary clause appears on the second page, suggesting that marriage is no substitute for food. (One wonders what Wiley's issue with marriage was.) Page 2 also has national news, including a detailed obituary of Henry Clay (1777-1852), an influential U.S. senator who had died the preceding June. The editorial column is also on this page, and though not entirely legible, part of it sums up The Columbian's purpose:

"But little ever has, or ever can be affected toward the consemmation [sic] of any important enterprise, without organization, unanimity, and harmony; and aside from the press, in a country like this, what means of affecting organization can be availed of? how unite its people for a concentration of action? or how harmonize conflicting opinions or prejudices on subjects in which all may have an interest? We know of none. Through the press all, can be heard — matters of public policy discussed, and such measures adopted as the wants of the people may demand. How important, then, is the establishment of a press in this country — to be not only established, but adequately sustained" (The Columbian, September 11, 1852, p. 2).

Page 3 includes a brief introduction of The Columbian under the names of Wiley and McElroy, asserting that the paper is "neutral in politics" and "devoted to the interests of Oregon in general and the territory north of the Columbia River in particular" (The Columbian, September 11, 1852, p. 3). The page includes ads for steamer travel to London and China, local rooming houses, grocers, and other merchants. And though Olympia may have been tiny in 1852, there's even an ad for a local law firm, Bigelow & Brooks. The final page of the paper is largely devoted to a speech given by one of the lawyers, Daniel Bigelow (1824-1905), at Olympia's July 4th celebration more than two months earlier.

Success and Struggle

Within six months the paper had 350 subscribers scattered throughout the proposed territory, despite a then-princely sum of $5 for a year's subscription (nearly $150 in 2017 dollars). As it had promised, The Columbian devoted itself to enthusiastically calling for the creation of a new territory, and it was able to claim success on April 25, 1853, when word reached Olympia that a bill establishing the new territory -- named Washington instead of Columbia -- had been signed by President Millard Fillmore (1800-1874) on March 2. Not only that, but the territory approved was far larger than what the Columbia/Washington settlers had sought.

Depending on which version you read, Wiley was either fired or resigned from the paper in March 1853. By this time McElroy was eager to get on with his life and tried unsuccessfully to coax Dryer into replacing him too. Wiley was replaced by J. J. Beebe, who lasted only until July, leaving McElroy to run the paper solo for the next two months. In September Matthew Smith took over as publisher and editor. McElroy remained as printing foreman through the The Columbian's final issue, published on November 26, 1853, when Wiley and Alfred Berry bought the paper and renamed it the Washington Pioneer. Yet now that McElroy could leave, he didn't. He stayed on as foreman at the Pioneer and its successor, the Pioneer and Democrat, until 1860. And he again worked with Wiley, who likewise stayed on until 1860, when his chronic drinking finally killed him.

The Ramage Press

The Columbian was printed on a press that already had a rich history when it arrived in Olympia in 1852. It was built about 1820 by Adam Ramage (1772-1850), a noted Philadelphia pressmaker. (It wasn't much different than a model Benjamin Franklin had used nearly a century earlier.) The machine was shipped to Mexico, where it was reportedly used by the Spanish to issue government proclamations.

After Mexico's 1821 independence from Spain, the press was mostly ignored until 1834, when it was shipped by burro (so the story goes) to Monterey, California, then part of Mexico. It was used to print more government proclamations and the like for some years, then abandoned. Discovered by the Americans when they arrived in Monterey in 1846, the press published the first newspaper in California, aptly named the Californian. It was later in the offices of San Francisco's Alta California for about a year before being shipped to Portland in 1850. There it printed the first issue of the Weekly Oregonian before being sent to Olympia two years later.

The machine's historical ride continued after its Columbian days. The press briefly printed the Washington Pioneer, then languished in Olympia for nearly a decade before, in 1863, turning out the The Washington Gazette -- soon renamed The Seattle Gazette (Seattle's first newspaper). Between 1867 and 1874 it printed Seattle's Weekly Intelligencer, a precursor to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, a daily that would run in print from 1881 until 2009. (A website continues, but it's not the same.)

The venerable Ramage press didn't last quite that long. Retired from active duty in 1874, it was eventually donated to the University of Washington Museum and later to Seattle's Museum of History and Industry, where it remains today.