For a time the carvings of artist Donald Wells Keys loomed over the Seattle skyline and around the Pacific Northwest. A 22-foot-tall Hoonah Raven inspired by Northwest Coast Indian art stood in front of Louie's Restaurant at 4th Avenue S and S Lander. There were two-story-high Tiki-style carvings on the beams of the Polynesia, a restaurant on Pier 51 along the downtown waterfront. In Seattle's north end, a 25-foot-tall Thunderbird totem pole stood at the entrance to Northwest Hospital. At Snoqualmie Pass, Keys carved the newel posts and hand-hewn benches for St. Bernard's Chapel. On the Kitsap Peninsula, Keys created significant pieces for the Kiana Lodge in Poulsbo. Dozens of works were created for banks and private collectors throughout the Northwest. A griffin crest for the Beta Theta Pi fraternity house at the University of Washington and a group of doves in the chapel of the Parkshore Retirement Community in Seattle's Madison Park neighborhood were carved from teak salvaged from the battleship USS Oregon. Keys's work received international attention when he replaced the masthead for the replica of British mariner Sir Francis Drake's ship the Golden Hinde. But nearly all of his works eventually disappeared from public view.

Alaska Born

Donald Wells Keys was born on August 13, 1911, in Chatanika, a gold-mining community near Fairbanks, Alaska.

In 1896 Don's grandfather, Edward McClellan Keys Sr. (1861-1950), had been drawn to the Yukon gold fields. After living in Circle City, in 1897 he and his family moved north to Dawson. Edward Keys Sr. was one of thousands who made the crossing over the famed Chilkoot Trail to the Yukon. Keys went on to serve as an Alaska territorial representative from 1923 to 1925, as well as being a member of the Board of Regents for the University of Alaska. At the end of his life, he lived at the Sitka Pioneer Home. In June 1950, at age 89, he went on a final mining trip, from which he did not return. His remains were found in a cabin at Ester Creek that November.

Mining in Alaska fast became a family tradition. Don Keys's father, Edward McClellan Keys Jr., worked as a mining engineer at Bonanza Creek, Alaska, and over the years lived in several locations in Alaska and the Pacific Northwest. In 1908 Edward Keys Jr. married Louise "Lula" Wells while living in Montesano in Grays Harbor County, Washington. By 1910, they moved to Cleary Creek in Alaska. Don was born while his parents and older brother Phillip (1910-1953) were living in Chatanika.

The Lower 48

When Don was about two years old, the family left Alaska for the outskirts of Arkadelphia, in Clark County, Arkansas, to stay with his mother's parents, William A. F. Wells and Sallie Lenore Ross. A Confederate cavalry veteran, his grandfather raised cattle and farmed. Don's younger brother Edward was born in Arkadelphia in 1913. Newspaper accounts from that year indicate that their father returned to Chatanika, where he continued to work in mining. It is unclear whether Lula and the children rejoined him in Chatanika.

By 1918, the Keys family returned to Montesano in Grays Harbor County, possibly to be near Lula's sister and brother-in-law. However, within a short time they moved back to Caddo, Arkansas, presumably when William Wells's health began to fail. In early 1920, the Keys family was listed in the census as living in Arkadelphia. That year brought the death of his Don's grandfather and the birth of his sister Sylvia Jean.

The Keys family came back again to Washington by 1922, this time to put down roots in Tacoma. Don attended Stadium High School there and it was then that he began to take a serious interest in carving. He began carving lessons with Wilhelm Bakke, a noted Norwegian-born artist and educator who later taught at Stadium High. In 1990, Keys recalled that after three lessons, he felt he had learned what he needed and wanted to set out on his own.

Back to Alaska

After high school, Keys went to Alaska and, like his father and grandfather, worked in mining, as well as hunting and running trap lines. From 1935 to 1937, he stayed with a Native Alaskan family. He spent time observing and learning carving from indigenous artists who created works for trade and personal use. At this time, the carving of totem poles and house poles had to an extent gone underground. These carvings were linked to potlatch ceremonies, which had long been discouraged or prohibited by both church and government authorities.

Keys was able to see examples of original totem and house poles in villages and may have had the opportunity to see some of the early restoration work that was being done by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) starting in 1938. He may have also seen the works of master Kwakwaka'wakw artists like Mungo Martin and Willie Seaweed, who kept ceremonial carving traditions alive, first in secret and then, when the potlatch prohibition was lifted in 1951, in public.

Love and War

While in Alaska, Keys met Mildred Louise Lovett (1904-1979), a pianist who made a living performing onboard ships traveling between Seattle, Vancouver, and Alaska. They married in 1938 and relocated to Seattle, where Keys took on work as an engineer at Washington Iron Works. They had one daughter, artist Lenore Keys Kobayashi (1942-2014). The family lived in the Wallingford area with Mildred's parents until her father's death in 1940 and her mother's passing in 1944.

During World War II, Keys served as a Boatswain's Mate 2nd Class aboard the submarine USS Anthedon in 1944, then in 1945 on the submarine USS Blower with the Advanced Training Relief Crew and on the USS Brill; he also served on the USS Sea Robin. His family recounts that it was while he was stationed in the South Pacific that Don was exposed to Polynesian carvings and architecture. According to a 1965 article in The Spectator, the photographs he took of these traditional structures and carvings during the war served as an influence on many of his large-scale works in the 1960s and 1970s.

A New Career in an Old Town

The post-war decade saw Keys return to the Seattle area, where he continued working as a heavy-equipment and crane operator. He assisted in building many structures on the University of Washington campus including some dormitories, a library at Seattle University, and other buildings around the Seattle area. In early 1953 his marriage to Mildred ended, and later that spring Keys married his childhood friend Evelyn Clare Miller (1915-2004), an artist and community activist. This was a second marriage for both. Keys became stepfather to Evelyn's daughter, artist Lyn Hopkins Kartiganer, who later became the director of the Seattle Arts Commission's Art in Public Places Program, and son James Miller Hopkins (1943-2011).

Don and Evelyn Keys were both active artists -- his carvings were primarily based on traditional Northwest Coast designs and Evelyn worked primarily in clay. They took classes and annual trips to Mexico to study art. Keys had created several smaller-scale totem poles and masks on commission and was eager to take on more work. Evelyn encouraged him to pursue a full-time career as an artist. In a September 1990 North Coast News interview Keys recalled Evelyn saying, "You've got the inclination and you've got the talent so let's see what you can do" (Fisher).

Keys's first big commercial break came in 1959, when Evelyn saw a blueprint for the new Northwest Hospital being built at Northgate near her doctor's office and noticed that it included a totem pole as part of the design. Evelyn contacted the architects, showed them photos of Don's work, and a deal was made. Keys further recounted that Evelyn persevered and took small examples of his carvings to all the major architectural firms in the area and really sold them on his work.

Thunderbird and Whale, Raven and Tiki

Keys felt very strongly that a pole should always be carved according to traditional Native designs and stories. The 22-foot-tall pole he carved for Northwest Hospital was his interpretation of a Northwest Coast story about Thunderbird saving a village that was being threatened by a whale. In a 1960 article from the University District Herald, Keys told the story of a whale destroying the villagers' nets, eating all the fish, and killing some of the men. Thunderbird killed the whale by bouncing a lightning bolt off its snout and then carried its carcass to the villagers for a feast. Keys stated that initially he had intended the pole to be of heavily oiled natural wood but later decided to paint the pole.

Around the same time, Keys created the impressive Tlingit-inspired Hoonah Raven entrance to Louie's Restaurant at 4th and Lander, owned by Louis Seidenverg (1919-2011). At nearly 25 feet tall, this dramatic piece loomed over 4th Avenue S for several years. In his book Life as Art, master carver Duane Pasco (b. 1932) refers to this sign as a significant source of inspiration for him: "I used to drool as I passed by on the way to work and dream of the day I could do something that good" (Life as Art, 19).

In a 2017 interview, Pasco referred to Keys as a warm and generous artist who encouraged him to pursue his interest in carving traditional Native American totem poles. Pasco added that as he learned more and refined his own skills, he could see that, while inspired, Keys did not strictly follow the formline tradition used by Native Northwest Coast artists and researched by University of Washington professor Bill Holm (b. 1925). While Keys stated he was a strict adherent to traditional Northwest Coast subject matter in his carvings, technically he was more imitative and less accurate in his execution, applying his own interpretations in the expression of lines and design. In 1980, Keys invited Pasco to speak at the Ocean Shores Friends of the Library and Associated Arts Conference. During this visit, Pasco said, he and Keys had a friendly carving competition, with Pasco using a traditional hand adze and Keys using a hydraulic one. Pasco recalled that the result was a tie.

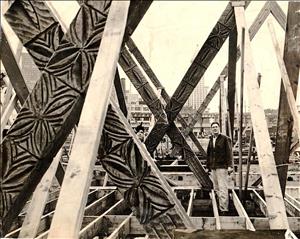

Also in the early 1960s, Keys was contracted to do structural carvings for the Polynesia, a new restaurant being built in downtown Seattle for owner David Cohn. Located on Pier 51, the restaurant was designed in 1961 by local architect Raymond H. Peck, who also designed such well-known Seattle structures as the Cinerama Theater and many Dick's Drive-In restaurants. Keys created Polynesian Tiki-style carvings for the external and internal two-story beams along with other decorative carvings for the restaurant on the pier. For more than 20 years the Polynesia presided over the waterfront, meeting its end in 1982 when the Washington State Ferries dock was expanded to encompass Pier 51. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported that the restaurant would be moved by barge to the Duwamish River.

Commissions Around the Region

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Don Keys created a wide variety of sculptures for clients ranging from Ivar's Acres of Clams, for which he carved two bears, one of which can still be seen at Ivar's Salmon House on Lake Union, to two Seattle Federal Savings and Loan branches, for which he created Thunderbird, bear, and beaver sculptures. A Seattle Times article from 1972 reported that after the bank's closure the Thunderbird was sold at auction to benefit the Seattle arts organization PONCHO. In 2017 a beaver pole could still be seen in front of the Wendy Amal Salon in Seattle's Madison Park.

Additional commissioned pieces included a sailboat prow carved in the image of Hawaii's King Kamehameha, twin seahorses carved for the Ocean Shores Inn in Grays Harbor County, and a carved laurel wreath to frame a "Winning Restaurant" plaque for Victor Rosellini's (1915-2003) renowned downtown Seattle restaurant. Keys created carvings for the Charles Island home of James Scripps, grandson of newspaper magnate Edward W. Scripps. Many of Keys's neighbors on Vashon Island and later in Ocean Shores commissioned pieces for their homes.

Keys collaborated with artist Mary Lou Patterson on a design for two newel posts at St. Bernard's Chapel at Snoqualmie Pass. Carved of yew wood, each post depicted an angel with head bowed and included a line from Scripture. One read, "O ye ice and snow bless ye the Lord," and other, "O ye frost and snow bless ye the Lord." (While the first disappeared at some point, the second remained inside the chapel as of 2017). Keys said in a 1990 interview that these carvings were completed around 1963 and were among his and his wife's favorites. He also carved the doors, pew ends, and lettering over the entrance at the chapel. All the pieces bear his distinctive deep adze marks. Other favorite pieces were those created using teak salvaged from the battleship USS Oregon. These include a six-foot-tall griffin crest for the Beta Theta Pi fraternity house at the University of Washington and a group of doves in flight in the chapel at the Parkshore Retirement Community in Madison Park.

Keys carved two pieces for the Kiana Lodge near Poulsbo on the Kitsap Peninsula -- a large bear executed in the same style as the surviving bear at Ivar's Salmon House and a Thunderbird pole. Kiana Lodge served as one of the Washington locations for the TV series Twin Peaks and both pieces make at least one appearance in the show. The bear is seen in the first episode of the first season alongside the character Audrey Horne, played by Sherilyn Fenn, and appears several times throughout the original series. The Thunderbird pole is shown in silhouette in the second season, episode 14. In 2017 Kiana Lodge manager Jay Mills (Suquamish) reported that the honey bear, as it was affectionately called by staff, was no longer in residence, but the Thunderbird remained on site.

Craft and Community

Teaching and demonstrating his craft was very important to Keys. He was a staple at arts fairs in Bellevue and Edmonds, demonstrating carving techniques to countless visitors, and a frequent speaker at numerous regional art talks and exhibitions. In the 1970s he worked with Vashon Island High School students in the Kiwanis-sponsored Key Club to build a totem pole for their campus.

Keys had the respect of many members of the Makah Tribe at the northwestern tip of the Olympic Peninsula. He carved a Naanee (the Kwakwaka'wakw/Waakashan word for grizzly bear) that was photographed at the home of Makah elder Mabel Robertson and her sister Helen Peterson. According to their niece, Melissa Renault (Makah), both were respected leaders, linguists, and tribal activists. Keys's personal papers indicate that two of his masks were on display at the Neah Bay Tribal Hall.

Keys also carved a Thunderbird totem pole and created a 13-foot mural for the Clearwater School in Queets on the Quinault Indian Reservation farther south on the Olympic Peninsula.

Kachina Lodge and Golden Hinde

Not all of Keys's work was done in the Pacific Northwest. In the spring of 1977, he was commissioned to finish a large sculpture at Kachina Lodge in Taos, New Mexico. The sculpture was the creation of Duane Van Vechten Lineberry, who was the adopted daughter of financier Ralph Van Vechten and niece of author and photographer Carl Van Vechten. The sculpture, Bird, Beast, Man and Infinity, was unfinished when Lineberry died in January 1977. Although completed according to Lineberry's design, Keys's style is evident in the treatment of the eyes and shaping of the coyote head in the center of the piece. According to W. Dean Koop, current owner of the Kachina Lodge Hotel, the carving is a major attraction for the lodge and still attracts a great deal of attention. The nine-foot-four-inch-tall pole is "a very unusual and distinctive piece" (Koop interview).

One of Keys's last major pieces was a departure from his established style. In 1987, the replica of the sixteenth-century ship commanded by British navigator and privateer Sir Francis Drake, The Golden Hinde II, was traveling around the world and lost its figurehead in a storm in the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Keys heard that the carving needed to be replaced and offered his services. Using a model deer head loaned to him from a taxidermy studio in Hoquiam and a small photograph of the ship, he recreated the figurehead using yellow cedar. For the eyes, Keys used polished walnut. The figurehead was installed while the ship was moored in Portland, Oregon. As of 2017 The Golden Hinde II was a tourist attraction at St. Mary Overie Dock on the Thames River in London.

Inspiration, Imitation, and Appropriation

Don Keys was a prime example of a skilled artist who was strongly influenced by and appreciative of an art style from a culture not his own. Although born in Alaska, Keys was not, nor did he ever claim to be, Native American or Alaskan Native. Looking at the body of his Native-inspired work, a strong case for cultural appropriation could be made. As a white artist, he enjoyed a level of privilege not afforded to Native American artists of his era and capitalized on art forms and traditions not from his own cultural background. While he studied style and technique, was very familiar with traditional stories, and often used traditional tools, Keys adapted both stories and techniques to create his own interpretation of traditional carvings. It is important to note that Keys also worked closely with Native communities on several projects and had a deep respect for Native culture and carving traditions.

His later years were difficult. His family noticed changes in his behavior that, while normally gregarious and boisterous, became more exaggerated. He was eventually diagnosed with Alzheimer's and ultimately lost his ability to create. Donald Keys passed away on January 21, 1995. His son-in-law Donald Kartiganer, a professor emeritus at the University of Mississippi, in his written eulogy, "For Don," captured the spirit of Donald Wells Keys:

"He was, as they said, a man's man -- which at times may have made him a little difficult for the women in his life but always a boon for the men. I had a vision of Don that could never be ... out of actual experience of him, but which framed him like a wall of old photos against which he moved. It was the vision of a past of Alaskan adventure, in which I imagined him as a tall, handsome, young roughneck whipping a sled-team of huskies across a barren snow-sunken world, hunting deer, moose and bear, out-drinking and out-fighting any man in the joint -- any man, that is, who refused to fall under the irresistible charm of his dazzling smile, his rollicking laughter, his generosity of spirit. This was the myth that accompanied him -- and by that I mean not that it wasn't true, but that it was the largest truth about him: larger than the life he actually lived, certainly larger than the life he would come to assume when his Alaskan days were done: it was the truth that held all the rest of his life in its legendary grip, like the empty shadows that give depth and dimension to the real objects of a painting" (Donald Kartiganer).

Fifty-seven years after it was installed, Don Keys's Thunderbird totem pole still stood at Northwest Hospital, one of only a few of his pieces still accessible to the public. By then it had been joined by works of such renowned artists as the late Canadian-born carver Dudley Carter and Susan Point (b. 1952) of the Musqueam Indian Band. In 2017, Eagle's Spirit, a new 27-foot-tall pole carved by nationally known artist David Boxley (Tsimshian) joined the collection. Boxley's pole commemorates the life of his sister-in-law Cindy Sue James. These newer carvings, images of welcoming, love, and gratitude, continue in the spirit of respect, strength, and pride that Don Keys sought to convey in all his work.