Puget Consumers Co-op (PCC), now called PCC Community Markets, started in 1953 as a food club in a Seattle basement. Since its early days, its primary focus has been on supplying consumers with natural and organic foods at competitive prices. Over an eventful 65 years, PCC has grown into a formidable retail presence, with stores in several Seattle neighborhoods and nearby communities. Through years of challenges and change, it has endeavored to stay true to the cooperative principles upon which it was founded. With 10 stores in operation in 2017, sales of more than $277 million, and plans for further expansion, PCC is a model of consumer-cooperative success and community involvement.

The Cooperative Movement

Rampant capitalism during the Industrial Revolution in England brought extreme wealth for a few and deep poverty for many. In response, a group of local tradespeople in Rochdale, near Manchester, formed the Rochdale Society of Pioneers and opened a cooperative store in 1844 on the delightfully named Toad Lane. The Rochdale Society is credited as the wellspring of the cooperative movement and of a set of ideals, called the Rochdale Principles, which in somewhat modified form still guide many cooperatives today.

The cooperative movement found fertile soil in America. The Grange, founded in 1867, was the first large one and is still active. The state's first recorded cooperative was the Skamokawa Farmers Creamery Association, a marketing co-op formed in 1898 by dairy farmers in Southwest Washington. Now, more than 100 years later, Washington has food cooperatives like PCC, electricity co-ops, outdoor-equipment co-ops, worker co-ops, housing co-ops, medical co-ops, cooperative banks and credit unions, artist co-ops, even funeral co-ops, among others.

Cooperatives are owned by their members, and the Rochdale Principles mandate democratic control by membership vote. The more complex a co-op's operations, the more difficult this becomes in practice. Strict adherence to broadly democratic decision making in all matters has led to deadlocks and failures. There appears to be no authoritative score sheet of successful and failed cooperatives, but a list of the latter would be substantially longer than a list of the former. PCC would rank near the top of any roster of vibrant, well-run cooperatives, but it has not achieved its success without challenges and compromise.

The Founder

John Affolter (1913-1997) emerged from the hardship of the Great Depression with a lifelong commitment to cooperative effort, utopian community, and pacifism. He moved from California to Minnesota to organize cooperatives shortly after World War II. There he met and married Ruth Waltonen (1918-2012). They moved in 1946 to Walla Walla, where a daughter, Jeanne was born in 1947. In 1949 the family moved to Seattle, where a son, Paul, was born that same year.

Affolter found Seattle to be "optimistic and idealistic" ("Mr. Co-op ..."), and before 1949 ended he had organized the Seattle Cooperative Housing Association (SCHA). For income, he sold policies for the newly established Group Health Cooperative and private insurance carriers, and he had the additional security of a moderate inheritance. In 1953 Affolter started a food club in his Seattle basement, and it is to this year that PCC dates its birth, if not its name. Affolter took orders from club members, then went directly to food producers to fill them, buying in bulk.

In 1955 Affolter and several other SCHA members purchased 37 acres east of Renton and formed the May Valley Co-op Community (MVC), a housing cooperative. MVC survived until 1977, when residents voted to eliminate all of its cooperative features and become just another neighborhood. But it had lasted for 22 years, almost a full generation and substantially longer than most other efforts at cooperative or communal living.

The Origins

Affolter kept the food club going in May Valley, and at a meeting on December 20, 1960, it was named Puget Consumers Co-op. In February 1961, 15 PCC members purchased the inventory and equipment from Affolter, who stayed on as manager. On August 29, 1961, the co-op was formally organized as a domestic corporation. Its bylaws specified that it would be run according to the Rochdale Principles. Eventually, this would prove much easier said than done.

The food club's inventory was quite limited, mostly bulk grains, dried beans, honey, and railroad-damaged canned goods. One of the original members, Elaine Stannard (1925-2011), recalled, "Either what we wanted was there or it wasn't there. Kids working in the Depot would let you know when something new came in" ("Celebrating 50 Years").

In 1967 the health department shut down Affolter's basement operation, and PCC, now with about 340 members, moved to its first storefront, in Seattle's Madrona neighborhood. With the exception of a paid manager, it was run by volunteers. Financing came from member dues, and goods were sold at cost. Affolter remained a member, but never again held an official position in the co-op's management.

John Affolter was idealistic and a purist, perhaps to a fault, with a strong belief in cooperatives and in the Rochdale Principles, including broad democratic control. Over the years, he accepted with somewhat grumpy good grace majority-vote decisions that increasingly did not reflect his strong beliefs. But he never gave up. Interviewed in 1988, he explained his persistence: "Well, setbacks really help. After all, idealism is self-liquidating. When you've achieved your ideals, what's left to do?" ("Mr. Co-op ...").

Finding Its Way

The Madrona location proved inconvenient for customers living north of downtown, and the co-op soon began a search for a location near Seattle's University District. A larger storefront was found, at 2261 N.E. 65th Street in Ravenna. In September 1969 the Ravenna PCC opened its doors, with a paid manager and a mix of paid workers and volunteers. Differences soon arose between those who believed PCC's emphasis should be on natural and organic foods and those who thought maintaining low prices was the highest priority. The natural-food advocates prevailed, and the store's product line increasingly reflected that preference.

The Ravenna store was an immediate success. By the summer of 1971, less than two years after it opened, membership had almost tripled, to nearly 1,000 households. PCC was doing well enough to help other cooperatives along, and in 1971 loaned seed money for an organization called Cooperating Community, a gathering of co-ops that did "everything from retailing produce and dry goods to providing day care and health care services" ("About PCC").

The move to Ravenna tapped into a deep pool of potential members, and if PCC was to attract and keep them it would have to offer more than just organic and natural foods. As Randy Lee, the manager of the Ravenna store who later became PCC's long-serving chief financial officer, explained at the time, "We're an in-between store. People who have always gone to supermarkets feel comfortable here because they see some familiar items. However, we have been trying to stock more organic foods and eliminate low-quality foods" ("What's Good About ...").

Some longtime members and staff soon thought the co-op had grown too large and were ready to move on. In late 1971 they turned in their PCC memberships and opened the Capitol Hill Co-op at 12th Avenue and Denny Way. To help them get started, PCC provided the names of its members for whom Capitol Hill would be more convenient than Ravenna.

Soon PCC was sharing more than just its expertise and customer list. In 1973 the Phinney Street Co-op opened, with financial help from PCC. In 1978 Central Co-op on Capitol Hill, a rebirth of the Capitol Hill Co-op, which had closed, received financial and technical assistance from PCC; it was still thriving 40 years later. But the competition did little to slow PCC's membership growth, and it continued to prosper.

Slow Growth: The 1970s

In 1972 staff at the Ravenna store succeeded in having the bylaws amended to allow up to four staff members on PCC's board of trustees and to adopt the same pay scale for all employees. PCC records these events as "the beginning of worker management of the co-op, which eventually develops into democratic management" ("About PCC"), the Rochdale Principle that would prove most difficult to adhere to in the coming years.

Membership and sales at the Ravenna PCC grew steadily through the 1970s. In 1975 PCC Mercantile was opened across the street to sell tools and other non-food items. It was not enough, and in 1976 PCC moved to a substantially larger space about two blocks away, at 6504 20th NE. The opening of that store marked a pivot point in the co-op's history. The new store attracted a slew of new members and sales soared.

In 1978 PCC leased the former site of Co-op East on NE 68th Street in Kirkland and opened its second store. Although small, it proved durable, and would eventually become the co-op's oldest location in continuous operation (but for a brief closure for remodeling). PCC's membership gains showed no evidence of slowing down.

In fact, growth was just getting started, and the co-op was being challenged by success. In 1961 total sales were $5,000; in 1975, they topped $2 million, and four years later, $6.2 million, with 12,500 member households. In 1979, the Ravenna PCC had to be closed to new members. The co-op commissioned its first demographic survey that year, and one common complaint was that many were "traveling long distances to shop at PCC because they can't find the quality and selection of products anywhere else" ("About PCC"). The co-op had a dilemma that most markets would envy -- how to meet an exploding demand for healthy foods at fair prices, a demand almost entirely of its own making.

Changing Times: The 1980s

In 1980 PCC opened its third store, near Green Lake at 6518 Fremont Avenue N and known as the Greenlake store. The ensuing decade brought three additional stores, at Seward Park (1985), View Ridge (1987), and West Seattle (1989). Growth brought both opportunities and problems. Democratic management at the Kirkland store was suspended for a year in 1981 after the store suffered dramatic losses. The next year saw the hiring of PCC's first general manager, a change from the "more passive Planning Coordinator structure" ("About PCC") that had until then sufficed. The business office was beefed up and the bylaws amended to limit staff to two seats on the board of trustees. Many did not like the changes, and in 1983 workers at the Kirkland and Greenlake stores, together with some office personnel, voted to be represented by the Retail Clerks Union, to be joined later by the staff of the Ravenna store. This was perhaps emblematic of changing times -- co-ops historically were seen as providing fairness and a participatory voice to employees, making union representation unnecessary.

During the 1980s PCC gradually departed from the Rochdale Principle of direct democracy, moving toward a system of strong, centralized management. This was unwelcome for many, but seen by most as necessary and inevitable. In 1985 Arthur Rasch, who taught cooperative organization in Chicago, opined that "the laissez-faire management attitude that was so attractive to co-ops in the '60s and '70s simply doesn't work today" ("Natural Evolution ..."). On PCC's labor side, Ken Rose, union steward at the Greenlake store, agreed: "The co-op can't go back to the democratic management of the '60s. We're talking a $13 million-a-year business. We've got 100 employees. Those days are gone'' ("Natural Evolution ..."). Michael Cohen, president of the PCC board of trustees, spoke for management: "You have to be successful as a business in order to be successful as a co-op. If business is not successful, a co-op will not survive, as we have seen elsewhere around the country'' ("Natural Evolution ..."). And The Seattle Times, reporting on the philosophical debate, commented, "today, the bottom line is ... well ... the bottom line, much the same as at Safeway or Albertson's" ("Natural Evolution ...").

John Affolter, who could be forgiven some paternal feelings toward PCC, did not agree. In 1988 he circulated a petition calling for more, not less, direct democracy. He cited as a cautionary example the failure that year of the Consumers' Cooperative of Berkeley, once the largest in the nation, with 12 outlets and $83 million in annual sales. Its demise in the 1980s was much analyzed, and many blamed it on the abandonment of the principle of broad democratic governance.

Affolter was respected by all but followed by few. Lyle Whiteman, the co-op's general manager at the time, said, "We all know and love John very much. But he's in a minority. I'm pleased to say the PCC is a very healthy, viable organization. We are very successful and extremely financially sound" ("Mr. Co-op ...). Whiteman proved correct on both points -- Affolter's effort failed, and PCC's growth continued unabated. But the board was not deaf to the voices of its staff and membership. During the late 1980s PCC held public forums and conducted surveys to gauge sentiment about further expansion. The board clearly was trying to strike a balance between too much democracy and not enough, a difficult task.

Growing Pains: The 1990s

Much happened with PCC in the 1990s, in both growth and governance, most easily understood with a straight chronology:

1991 -- PCC purchased the Meat Shop, Inc., a failed butchers' cooperative that had been selling organically raised meats through PCC. Its workers become PCC staff, represented by UFCW Local 81.

1992 -- PCC made one of its few major missteps, opening a seventh store, in South Everett, that did poorly and closed three years later.

1994 -- PCC opened its first outlet in Fremont and added a full-service deli to the Ravenna store. In that same year, it contracted with a small farm in Eastern Washington for organic eggs, becoming the first in Puget Sound to offer them. PCC also initiated the local market for organic milk, partnering with two Washington dairies. Other initiatives included a pledge to not knowingly sell food that had been irradiated, and eliminating bovine growth hormone (rBGH) from all dairy products.

1995 -- PCC's board of trustees decided to close the South Everett store without consulting the membership. After protests, a vote by that store's members was held. By a large margin they voted to keep the store open, but the board overruled them and closed it anyway. This appears to have been the first time that the board disregarded a membership vote on such an important issue. A PCC spokesperson, Theresa Steig, told The Seattle Times, "We are large enough that not everyone is involved with every decision and they haven't been for years and years. It's been over 20 years in this organization since we've had all members involved in all decisions" ("Members Upset ...").

That may well have been true, but the South Everett kerfuffle illuminated the fact that PCC's governance had fallen between two stools: Forced by size and circumstances to move away from the ideal of direct democracy, it had not adopted a cohesive and consistent alternative. Clear guidelines were needed, ones that would allow the board of trustees to make critical business decisions while honoring to the extent possible the democratic traditions of member-owned cooperatives. The board started looking for a solution.

1996 -- The original Greenlake store moved to a larger site, at 7504 Aurora Avenue N., a building that formerly housed the Greenlake Market. A new price structure that eliminated an additional markup for nonmembers was introduced.

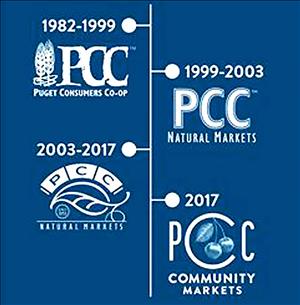

1998 -- PCC Consumers Co-op changed its name to PCC Natural Markets, to make clear that it was a food store, one that emphasized natural and organic products. This was also the year that the board of trustees, three years after the closure at South Everett, adopted the "Carver Policy Governance® Model," a comprehensive and widely used template for the conduct of directors or trustees, whether serving for-profit or nonprofit corporations. A basic Carver premise for nonprofit consumer co-ops is that a board's duty is to the organization's members, not to staff or management. A full description is far beyond the scope of this essay (entire books have been written about it). It must suffice to say that the Carver model prescribes what is expected of a board of trustees, assigns to it responsibility for determining organizational ends and defining acceptable means for achieving those ends, clarifies the relationship between the board and the person to whom it has delegated authority (i.e. the CEO), and requires that the board regularly monitor top management's performance to ensure that its clearly defined ends are being achieved. Dry stuff to most, but for PCC the Carver model brought greater clarity and consistency. It is not without its critics, both within the cooperative community and in academe, but it is probably not a coincidence that two decades of great growth and financial success followed PCC's adoption of the Carver model.

1999 -- PCC opened its largest store to date, 24,000 square feet, in Issaquah.

A New Century

The first decade of the twenty-first century saw steadily increasing sales and slow but methodical expansion. PCC's flagship Ravenna store was closed in 2001, largely due to tough competition, including Whole Foods, which in 1999 had opened the largest natural-foods supermarket in the country less than two-thirds of a mile away. The Ravenna property was sold to Third Place Books, a community-oriented seller of new and used books. Despite this setback, PCC's sales in 2002 topped $75 million.

In 2003 a new and larger Fremont store was opened, at 600 N 34th Street, and the entire PCC chain obtained organic certification from the Washington State Department of Agriculture. In 2006 the Redmond PCC opened, followed in 2008 by a store in Edmonds.

Between 2003 and 2013 PCC's total sales doubled, from $100 million to $200 million. In 2014 a new store was opened at Greenlake Village. The Seward Park store was relocated to Columbia City in 2015, with the old location again being sold to Third Place Books. The following year, WholeFood Magazine recognized PCC as retailer of the year for "successfully [striking] that balance between running a business and representing the values of its 56,000 co-op members" ("About PCC").

In the second half of the second decade of the twenty-first century, PCC's expansion accelerated. A new store opened in Bothell in 2016. In 2017 the co-op's name was changed to PCC Community Markets "to better reflect its community ownership and commitment to the Pacific Northwest" ("About PCC"). Among new stores then planned or underway was one in Madison Valley, as the anchor tenant in a mixed-use development, and one in Burien, both to be opened in 2018. The West Seattle store was closed in 2017 for a reconstruction doubling its size, to be reopened in 2019.

The pace did not slow in 2018. In January PCC announced plans to open a new store in Ballard at 1451 NW 46th Street in the spring of 2019. And on March 9, 2018, came the announcement that PCC would be the anchor retail tenant on the ground floor of the Rainier Square project in downtown Seattle. Ironically, all of the new building's office space was to be occupied by Amazon, owner of competitor Whole Foods. Completion of these projects will bring PCC's store count to 15.

Doing Well and Doing Good

Even as growth and success led PCC to depart from strict adherence to the Rochdale Pioneers' requirement of democratic decision making, it worked very hard to live up to the full spirit of the other Rochdale Principles, one of which emphasizes education, training, and proselytizing for cooperative organizations. As noted above, PCC helped other cooperatives get started, giving both financial and technical assistance. Its newsletter, which started in the early 1960s as a mimeographed sheet, is now Sound Consumer, a full-color monthly publication covering a wide variety of topics. In addition, PCC over the years has offered classes and training on a range subjects, many traditional, some with a New Age slant. A random sampling from the first six months of 1983 included tips for shopping wisely, garden-planning workshops, healthy food for children, nutrition during pregnancy, and "visualization and well-being" ("Well-being Is Topic"). PCC also launched a nutrition-and-cooking-education program in 1983 called Foodworks! (later changed to PCC Cooks) that by 2017 was offering hundreds of cooking classes a year.

Another Rochdale Principle (as modified in 1996) requires that "cooperatives work for the sustainable development of their communities through policies approved by their members" ("The Rochdale Principles"). Even before it was added, PCC honored this principle in myriad ways. One example dates to 1973, when the city of Seattle acquired an abandoned three-acre truck farm at 25th Avenue NE and NE 82nd Street and turned it over to PCC for management. Working with the community, PCC helped develop the land into more than 250 separate gardening plots, which marked the start of Seattle's flourishing P-Patch program. Forty-five years later it still existed, as Picardo Farm, and there were 88 such community gardens all across the city where organic gardening produced food for local green thumbs and food banks.

Two other lasting accomplishments came in 1999. On the national level, PCC was a key player in the birth of National Co+op Grocers (NCG), a business-services cooperative that "helps unify food co-ops in order to optimize operational and marketing resources, strengthen purchasing power, and ultimately offer more value to food co-op shoppers everywhere" ("Putting It All Together ..."). By 2018 NCG had 147 member and associate co-ops that operated more than 200 stores in 37 states, with combined annual sales of more than $2.1 billion.

Of regional import, in October 1999 PCC launched the PCC Farmland Trust, an independent nonprofit organization that "secures, preserves, and stewards threatened farmland in the Northwest, to ensure that generations of local farmers productively farm it using sustainable, organic growing methods" ("2008 Annual Report"). Its first project, funded by PCC alone, preserved from development 100 acres of farmland in the Sequim-Dungeness Valley on the Olympic Peninsula; the land is now home to Nash's Organic Produce. By 2018 the Farmland Trust, with financial support from PCC, its members and suppliers, grants, and public contributions, had preserved 20 farm properties totaling 2,040 acres, ranging from Walla Walla to Whidbey Island. Many products from trust-protected properties are sold at PCC stores, but the farms are independent and do business with whomever they like.

PCC has also been a prominent voice in the national debates over organic food and in opposition to experiments in food modification. In a display of organizational muscle, PCC members in 1997 submitted more than 30,000 comments to the U.S. Department of Agriculture regarding proposed national standards for organic foodstuffs. These represented more than 10 percent of all comments received by the department on the issue. Three years later, 12,000 PCC members wrote Congress to urge full disclosure of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) in the nation's food supply.

In 2004 PCC became the nation's first food retailer to participate in Monterey Bay Aquarium's Seafood Watch Program, which helps consumers and businesses choose seafood that's fished or farmed in ways that support a healthy ocean. In 2009 Greenpeace awarded PCC the number-one ranking among all U.S. retailers for selling sustainable seafood, both fresh and canned.

PCC Community Markets is an uncommon, perhaps unique, success story in the history of consumer food co-ops, with growth and profitability that would be the envy of any for-profit grocery chain. In 2017, membership numbered more than 60,000 households, sales exceeded $277 million, and net profit was $7.6 million, nearly 40 percent above 2015. That PCC has accomplished all this while maintaining a high degree of fidelity to traditional cooperative principles is remarkable and admirable, and the end is nowhere in sight.