Naval Base Kitsap-Bangor on Hood Canal was a vital ammunition depot from late in World War II to the end of the Vietnam War, and the segregation area was one of its key components. The Bangor depot was built in 1944 and 1945 northwest of Bremerton in Kitsap County. A railroad line was carved through challenging terrain to connect the depot with the closest existing tracks, at Shelton in Mason County, about 45 miles south. The railroad and the depot were built on a frantic schedule so Bangor could contribute to the anticipated invasion of the Japanese mainland. The segregation area was a small collection of concrete buildings between two lines of railroad tracks, bordered by earthen barriers. Munitions were sorted there and directed to assembly, storage, or shipping areas. After World War II, transshipment of ammunition rose and fell depending on U.S. military missions. It peaked again during the Vietnam War, when Bangor was the closest U.S. ammunition depot to Southeast Asia. Later the depot became a submarine base and the segregation area was abandoned with 45 railroad boxcars still on its tracks. The buildings were razed in 2015, with the boxcars scheduled to be demolished in 2018.

Historically, navy ammunition depots have assembled, stored, and loaded ordnance -- weaponry such as bombs, mines, high explosives, un-fused projectiles, and small-arms ammunition. The depots are located near shipyards, because a ship must off-load its ordnance before it can enter the yard. The process is reversed when the ship is ready to return to sea. Similarly, when a new vessel is commissioned, it starts its voyage by heading to an ammunition depot to pick up ordnance.

War Creates a Need

Leading up to the U.S. entrance into World War II, the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard at Bremerton, across Puget Sound from Seattle, was the main navy yard on the West Coast and the only one capable of servicing aircraft carriers and battleships. There was one ammunition depot near it, Navy Ammunition Depot (NAD) Puget Sound on Ostrich Bay in Bremerton. With war already raging in Europe, that depot had more work than it could handle. Another depot, Naval Magazine Indian Island, was added at the north end of Puget Sound near Port Townsend in 1941. After the December 7th Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor plunged the United States into the war, the flow of ammunition ramped up dramatically. Puget Sound's two ammunition depots were swamped.

They also had drawbacks. Neither had a deepwater dock that could accommodate the largest naval vessels. And neither was connected to rail, meaning ordnance coming by rail from inland production plants had to go first to commercial docks in Seattle. There the boxcars were loaded onto barges to complete the trip to the depots. The one closest to the shipyard, NAD Puget Sound, was particularly problematic. Its rail system was narrow gauge, so standard-gauge rail cars could not use the depot's railroad system. Instead they had to be unloaded while still on the barge, a slow and cumbersome process, before munitions could enter storage areas.

By 1943, the U.S. Navy was looking for a site to build a new Puget Sound ammunition depot. Captain J. W. Rankin, commander for NAD Puget Sound, said it should be near existing rail lines and highways, and have a deepwater dock and enough standard-gauge track storage to handle the sorting of railroad cars.

Big Plans for Bangor

Bangor, a small Kitsap County community 16 miles northwest of Bremerton on the east shore of Hood Canal, was chosen for several reasons. Hood Canal offered a direct route to the Pacific Ocean, via the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and it was deep, with no obstructions and only light commercial and recreational traffic. The site was relatively undeveloped, which figured to make land acquisition easier than in more settled areas, and it was big enough to allow for expansion if needed. Getting it ready for service would require construction of a wharf along the shoreline. It also would require building a rail line connecting it to the closest commercial line, Northern Pacific Railway's tracks some 45 miles away at Shelton in Mason County.

The Secretary of the Navy approved plans on April 28, 1944, releasing $18.7 million (nearly $265 million in 2018 dollars) for the railroad, naval magazine, and transshipment project. Preliminary estimates pegged the cost of the depot at slightly more than half the total and the railroad costs at roughly a third. The project was quickly launched, as it was deemed critical to a final push to end the war in the Pacific.

The Bangor depot was officially established as a subordinate command of NAD Puget Sound in June 1944 and construction began that same month on its wharf. That structure had two piers, one of them 1,200 feet long. One pier was ready by November and the entire wharf project was finished by the following January, making it the first portion of the depot to be completed.

Acquiring the Land

Before construction on the railroad and depot started and while it was underway, the navy was negotiating to acquire privately owned property needed for the project -- an estimated 6,750 acres for the depot and 594 acres for the railroad right-of-way. It wasn't easy. The railroad route alone involved 400 separate parcels. Navy representatives dealt directly with the landowners, buying the land if an agreement could be reached or obtaining it by court order. The owners were allowed to remove their buildings if they chose to do so.

A 90-year-old man told the Kitsap Sun in November 2017 about his family being relocated from their property near Hood Canal in 1944. He was a teenager at the time. The first indication was the sudden appearance of a surveying crew on the property. Buz Whiteley recalled, "Nobody would say what it was for. They weren't allowed to tell anybody what they were doing" (Stanford). The navy later offered $17,000 for the property. The family "didn't quibble" about the price, Whitely said, but balked when initially given only 30 days to move (Stanford). They gained an extension, bought back the house, barn, and garage for $500 and moved -- buildings and all -- to Port Gamble.

Not all owners were as agreeable. There was enough resistance that the navy considered adjusting the depot's southwestern boundary to keep the project moving. Three hundred fifty families living on the Bangor site were given three months to vacate their land. Ultimately, about 1,100 people relocated and most structures on the annexed land were demolished.

Building the Railroad

A far bigger challenge was building the railroad. The total length was 85 miles, including branch lines to the shipyard in Bremerton, the ammunition depot at Ostrich Bay, and spurs within the Bangor depot. About 60 of those miles were essentially wilderness. Surveyors already had laid out a route through the narrow isthmus near Belfair. Much of the terrain was steep canyons, deep bogs, and nearly impenetrable forests packed with tall firs and hemlocks along with thousands of trees blown down by wind. The first task facing workers was to clear a path at least 100 feet wide along the entire route.

It was a rush job. The work was to be completed by December 1944. The two prime contractors were General Construction Company and Sound-Kiewit Company, both based in Seattle. They employed dozens of subcontractors and a staggering amount of heavy machinery.

Clearing and grubbing (removal of trees, shrubs, and stumps) began on May 11, 1944, on the Mason County section and on June 28, 1944, on the Kitsap County section. In the most challenging areas, workers and bulldozers cleared an average of one acre a day. The next step was grading, made more difficult by glacial gravel so tough and abrasive that heavy-duty rooters were needed to prepare the path for scrapers. Peat bogs were covered with a layer of felled trees and swamps were excavated to solid ground before fill material was added. Cuts up to 80 feet high and fills up to 60 feet deep reportedly were common. After grading, tracklaying commenced with ties being placed by hand, rails set by a crane mounted on a small, self-propelled rail car, and spikes set first by hand and then driven by pneumatic spikers. Tracklaying began in July 1944 and was completed by November. The final step was adding ballast, crushed stone that adds stability, drainage, and support for the tracks. That was accomplished by a steam locomotive pulling center-dump ballast cars. A bulldozer following those cars smoothed the ballast they had unloaded.

The Shelton-Bangor Railroad became operational on January 25, 1945, and in April, Northern Pacific took charge of its operation. The new line was officially commissioned on August 10, the same week the United States dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Depot and Segregation Area Take Shape

The emerging Bangor depot had three general areas spread over more than 7,000 acres: the two-trestle marginal wharf on the northwest end, administrative and industrial buildings near the southeast end, and ammunition-storage areas called magazines (concrete bunkers covered with earth) roughly in the middle. Linking them was some 60 miles of railroad. As originally developed, the depot had 41 five-car barricaded sidings, a 250-car classification yard, 39 magazines, nine storehouses, a transfer-and-segregation group of buildings, four permanent and one temporary barracks, and administration and shop buildings. Construction in 1945 added more magazines, raising the total to more than 100 by September.

The main rail line entered the depot from the south and traveled along its western edge to the wharf. A spur near the entrance headed to the classification yard where incoming boxcars were examined for the type of ammunition they carried and shunted to the appropriate next stop. Farther down the line, past some temporary storage areas were two separate lines leading to the segregation area.

Also called the sorting complex, the segregation area and its buildings were designed by the Chicago architectural firm of Shaw, Naess, and Murphy. Sound-Kiewit Company of Seattle was the contractor. The area was 365 feet long by 1,300 feet wide. It had two parallel lines of tracks. Between them was a string of three sorting buildings where ammunition was separated by type and sent to the appropriate destination. Those rectangular, one-story buildings were erected between late July 1944 and late February 1945. They were made of reinforced concrete and had corrugated transit hip roofs covered with asbestos material. The roofs were 30 feet long and 11.7 feet wide, overhanging the buildings by 12 feet. Linking the buildings and the tracks were concrete platforms much like the boarding platforms at civilian train stations.

Importantly, the outside borders of the segregation area were marked by earthen barricades built to meet standards prompted by deadly explosions at an ammunition depot at Lake Denmark, New Jersey, in 1926. That disaster, triggered by lightning, destroyed all buildings within a 2,700-foot radius, demonstrating the critical need to confine the effects of accidental explosions. Consequently, Bangor's segregation area was flanked by tapered earthen barricades that were 21 feet high and 52 feet wide at the base, and had 15-foot-high concrete blast barriers on both ends. Spaced evenly between light poles along each barricade were a dozen 58-foot lightning rods.

Even before the rail line was officially commissioned, the first ammunition train entered Bangor on April 14, 1945. In the remaining months of the war, the Shelton-Bangor Railroad transported some 6,000 loads, most of them munitions. Reports prepared for the navy on the history of the Bangor depot and its segregation area focus on the buildings and railroad; they do not mention who worked there during those months. Judging from staffing at the naval shipyard in Bremerton, the work force would have been mostly civilians, many of them recruited from other parts of the country, and a fair share of them women.

From Korea to Vietnam

After World War II, activity at Bangor ebbed in peacetime and surged during military conflicts. The Cold War against the Soviet Union caused a brief increase in ammunition handling, but in 1949 cutbacks reduced Bangor's status to backup depot, with personnel cut from 910 to 142 civilians and stores of ammunition allowed to diminish. That changed during the Korean War (1950-1953), when Bangor provided ordnance for the army and air force as well as the navy and gained $4 million worth of improvements.

While continuing to be a major ammunition depot, Bangor in 1962 was linked for the first time with nuclear weapons. It was selected to assemble and store Polaris missiles. About $44 million was spent on the assembly plant, which was expected to employ several hundred workers and was commissioned in 1964 as the Polaris Missile Facility, Pacific. The commissioning ceremony was attended by Secretary of the Navy Paul H. Nitze (1907-2004) and Vice Admiral Hyman Rickover (1900-1986), an early proponent of nuclear-powered ships and submarines. Protestors stood outside the main gate and three tried to block traffic, examples of peace demonstrations that grew as Bangor got more involved with nuclear weapons.

Bangor's handling of conventional weapons waned after the Korean War until 1965 when President Lyndon Johnson (1908-1973) began to significantly escalate the U.S. role in the Vietnam War. About half of all the weaponry sent to Southeast Asia during that conflict passed through the Bangor depot. Most of it came by rail. Seven thousand boxcars arrived via the Shelton-Bangor Railroad between March 1967 and March 1968. They were met by civil-service crews and moved to the depot's classification yard. Boxcars then went to the segregation area for sorting. Finally they were unloaded either at storage magazines or at the wharf, where munitions were loaded onto ships bound for the fighting. At times traffic was so great that waiting ammunition was temporarily stored on barges anchored in the harbor.

A New Mission

For its first 32 years, Bangor's chief mission was handling and storing conventional weapons. That changed after the Vietnam War. In 1977 Naval Ammunition Depot-Bangor was closed and the area was commissioned as Naval Submarine Base-Bangor -- intended to be home for half of the nation's fleet of Trident submarines. The first of those nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed subs arrived in August 1982 amid on-going protests by peace activists.

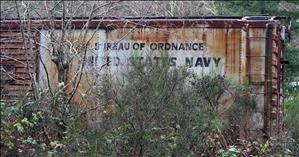

With the change of mission, the segregation area and other components of the ammunition-handling depot were abandoned, with 45 boxcars left standing on the segregation area tracks. In 2013, the navy announced plans to demolish the segregation area, saying that was necessary to eliminate excess buildings and the associated maintenance costs, energy use, and safety hazards. The buildings were demolished by navy contractors in 2015 and native vegetation was planted.

The boxcars, after more than 30 years on the site, were rusting hulks. The navy tried to find a home for some of them at several museums but was unsuccessful. Their demolition was planned for spring 2018. That would leave only empty tracks in what had been one of the ammunition depot's busiest areas.