On May 24, 1942, a U.S. Army Recreation Center opens on Seattle's Beacon Hill. Accommodating 1,000 military guests, the recreation center is located in a section of the city's Jefferson Park. The center is largely funded by local organizations that donate building materials and equipment, and built by army engineers and Civilian Conversation Corps (CCC) workers. A total of 84 structures are erected to provide lodging and recreation for service men and women. With the Seattle area bustling with military personnel during World War II, the Jefferson Park recreation center quickly becomes a popular attraction, its attendance exceeding 50,000 service members per month. In 1945, the city of Seattle will donate the southern part of the recreation-area site to the Veterans Administration for a hospital, which will open in 1951 and expand over the following decades. After the army closes the recreation center on February 28, 1946, the city will demolish the structures and eventually develop the Jefferson Park Playfield on the northern portion of the site.

Stepping Up to Build an Army Recreation Center

In late November 1941, shortly before the United States entered World War II, the Seattle Board of Park Commissioners approved a U.S. Army proposal for an Army Recreation Center to be developed on the west side of Jefferson Park, located on Beacon Hill south of downtown Seattle. The park had opened in 1908, with a municipal golf course added in 1915. Following the park board decision, the Seattle City Council voted to sign a lease agreement with the army for the park site. In March 1942 an army engineer group and and CCC workers started construction of the recreation center. In addition to the recreation center, Seattle allowed the army to install antiaircraft guns on the Jefferson Park Golf Course, providing protection for the Boeing airplane-construction plant to the south below Beacon Hill. The recreation center was built on 100 acres between the park's western boundary and 16th Avenue South. Although the army built it, the center served all military branches with accommodations for 1,000 guests for overnight and longer stays. Before the war ended it expanded to include a hotel for women service members and a women's recreation program.

Major Ralph J. Sitts (1898-1969), who grew up in the small Grant County town of Hartline in North Central Washington, arrived in March 1942 to oversee construction and then command the recreation center. Sitts had joined the army following his graduation from Hartline High School in June 1918. He served in a motor truck company in France during World War I and returned home in January 1919. Sitts resumed a civilian career as a salesman and later a state employee. He also served in the National Guard, reaching the rank of captain. On September 19, 1940, he returned to active service in the Quartermaster Corps. In 1941 Sitts was promoted to major.

The Jefferson Park recreation center was a test of his ability to complete projects with extremely limited funding. Employing army engineers and Civilian Conservation Corps workers and using surplus material, Major Sitts built the center at a fraction of what it would have cost to contract out the work. To make his life more difficult, the War Department cut funding just as the center opened. With no additional funds, sleeping quarters went uncompleted. This left soldiers to sleep on cots outside under the trees. Not a problem in the summer, but outdoor sleeping would not work well in the winter. An appeal went out to Seattle groups for help and they responded with contributions to finish the project. When the final building and equipment cost was calculated, local organizations had contributed 88 percent of the total. Contributions ranged from chairs and tables to pieces of broken concrete sidewalk donated by the city of Seattle. The concrete pieces were laid down as sidewalks. Local groups led fundraising efforts to supply the center. Mary Hoge Agnew (1896-1968), daughter of pioneer James D. Hoge (1872-1929) for whom Seattle's Hoge Building was named, led a Sunset Club campaign that raised enough to equip three day rooms. The Seattle Lions Club and other organizations helped fund a large roller rink.

Recreation and Entertainment for Service Members

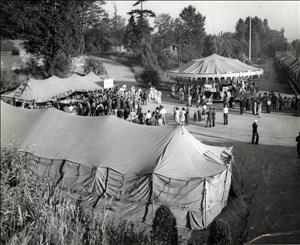

At its peak the center had 84 structures, mostly winterized tents on wood platforms, including a cafeteria, clubhouse, women's hotel, nursery, officer's hotel, and bathhouse. There was a Post Exchange, tailor shop, and barber shop. Most everything in the center was free except for food and cigarettes. One building housed a civilian clearing house where members of the community could come to provide rides and donate sports equipment, nursery items, and other essentials. Civilians called the center to invite service members to their homes for meals and then met their military guests at the civilian clearing house to take them home. The clearing house published in local newspapers a request for skis and equipment. More than 160 sets of skis and equipment were collected and made available for loan to service members. During the ski season two army buses took service members to Snoqualmie Pass. However, more than two busloads generally wanted to go skiing, so civilian skiers heading to the pass were asked to take along a service member if they had room as they caravanned by auto to the ski area. Soldiers were also treated to boat rides and salmon fishing. For many this would be their first time on skis or salmon fishing.

Entertainment at the recreation center included a midway with carnival activities. The most popular attractions were the merry-go-round and roller rink. Evenings featured movies and special events such as boxing matches, band concerts, and live shows. Prominent Seattle boxing promoter Nathan "Nate" Druxman (1892-1969) brought top boxers to the center for boxing matches. One activity enjoyed by participants and spectators was donkey baseball. A local owner of trained donkeys brought them to the center where service members played baseball while riding the animals. It made for a fun game. The center had a golf program that provided golf clubs. Service members could golf nine holes at the Jefferson Park course for 25 cents. Guests at the center could learn archery and practice at an archery course there. For those just relaxing there were had reading materials. Seattle residents donated thousands of magazines and books.

On May 8, 1943, a 43-room servicewomen's guesthouse opened. It offered guest rooms and spaces to relax. The women's guesthouse had comfortable rooms with fireplaces and tables for card playing and socializing. The building materials were donated by the Seattle Rotary Club and the furnishings by the local Fraternal Order of Eagles. By this time the Jefferson Park Army Recreation Center was one of the largest in the nation. Every month it grew in popularity. In October 1943 the monthly attendance was more than 50,000 service men and women. Not only did were men treated to fishing trips, but women had fishing parties. Servicewomen from all the branches would attend -- there would be Army WACs (Women's Army Corps), Coast Guard SPARS (from the Coast Guard motto "Semper Paratus," meaning "Always Ready"), Navy WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service), and U.S. Marine Corps Women's Reserve. Completion of the women's guesthouse brought the center's cost to $300,000. Seattle residents and businesses had donated all but $24,000 of this amount.

Closing and Reuse

By 1945, as large numbers of injured war veterans arrived in the Seattle area, it was clear that additional medical care facilities were required. The Veterans Administration (later the Department of Veterans Affairs) realized a veterans' hospital was needed. In July 1945 the Seattle City Council donated a 44-acre site in the southern portion of the Jefferson Park recreation area for a hospital. Construction of the $8-million hospital began in 1949. The Veterans Administration Primary Care Hospital with 325 beds was dedicated on May 15, 1951. Its first patients were admitted in late May. A research wing was added in 1967. A second medical-care facility opened on the site in 1985 and in 2017 a six-story mental health care facility opened.

In September 1945, a month after World War II ended, the army announced it would close the Jefferson Park recreation center that November 1. With the war over it was expected that demand would drop. However, many service men and women would still be passing through Seattle on their way home, and the crowded military hospitals in the area would be receiving patients whose recovery could benefit from recreation. Seattle Mayor William F. Devin (1898-1982) protested the planned closure, citing this ongoing need. The City Council and others joined in the call to keep the recreation center open. In response, army officials agreed to keep the center open until further notice. Finally, following a dramatic decline in use, it closed on February 28, 1946.

On March 31, 1946, the center was declared surplus and the process to return it to the city was initiated. That May disposal of the former recreation center's equipment began. Approximately 500 golf clubs were donated to Seattle for its junior golf program. Building disposition, however, did not go so smoothly. While Seattle organizations and citizens had donated much of the construction material, army officials argued that the buildings' total value belonged to the army. Negotiations led to an agreement that the value of the buildings approximately equaled the city's cost to restore the site, and on that basis Seattle acquired the 84 structures on its land. However, the structures were flimsy and most were removed or demolished.

Debate followed on what to do with four larger buildings. In 1947 possible reuse of the roller rink with its gym-sized floor was debated. Some in the community wanted the structure retained for use as a gymnasium. The Board of Park Commissioners favored demolition, on the grounds that the building was poorly constructed and a fire hazard, and did not meet city code. It also lacked adequate bathroom facilities. The final decision was demolition. No other buildings were retained; instead the structures were sold as lumber at discount rates to veterans. The Jefferson Park Playfield was eventually built over the northern portion of the former recreation center.