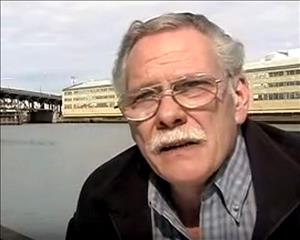

This People's History, written by Stephen Miller, tells of the life of John Beal, a U.S. Marine Corps veteran who suffered physical injuries and severe psychological harm while serving in Vietnam, but later found a purpose in life restoring pollution-damaged Hamm Creek and fighting for the restoration of the Duwamish River, both located in South Seattle. In the year before his death, Beal's testimony was instrumental in the 2007 creation of the Veterans Conservation Corps by the state legislature. He was widely honored for his efforts, and each year the Duwamish Alive Coalition presents the John Beal Environmental Stewardship Award to honor the spirit he exhibited.

A Formidable Advocate

John Beal used to say that he and the Green-Duwamish River were one. Indeed, his life seemed intrinsically tied to it and, in particular, to a forgotten creek that followed a degraded course through his neighborhood in South Seattle. Soon after returning home from the war in Vietnam -- a young man with deep physical and emotional wounds -- Beal suffered a series of heart attacks and was given only months to live. Devastated, he went to sit in a wooded grove beside Hamm Creek, a tributary of the Duwamish River that was so polluted it no longer resembled a natural watercourse. Something in him snapped that day, and he committed himself to spending what time he had left restoring the creek. Sustained by this purpose, Beal spent the next 27 years rehabilitating Hamm Creek and, eventually, the Duwamish, a river that had lost its natural identity and was largely viewed as a commercial waterway and dumping ground. His work led to one of the most substantial environmental restoration efforts in Seattle's history.

The grit and dogged determination that earned Beal the nickname "Johnny the Terror" in Vietnam made him a formidably unshakable advocate for the river and creek's wetlands during near-constant battles with commercial interests and uninterested government officials. Despite an often irascible personality, his passion for the river was a beacon for enthusiastic volunteers, an inspiration to curious school children, and sparked a movement of restoration that rehabilitated acres of wetland and won Superfund protection status with the Environmental Protection Agency. Although his life ended with a bitter defeat in a final battle to protect the source of the creek, his legacy of environmental stewardship still remains a powerful force in the region.

Early Life

John Charles Beal was born on January 22, 1950 in Butte, Montana to Harold Chauncey Beal and Jean Elizabeth Powers. Harold, an orthodontist, died suddenly of a heart attack just a month after Beal was born. Jean remarried, to Robert Whitney, who moved the family to the Spokane valley in Washington in 1953.

Due to complications at birth, Beal was color blind and severely nearsighted. He was also dyslexic, which, coupled with his sight problems made school particularly difficult. He attended North Pines Junior High school, where he met his future wife, Lana Jesse Stout (b. 1950), and Central Valley High School, where he played guitar and sang in an Elvis-inspired band. From an early age, Beal was more comfortable with the natural world than the classroom. He explored the open lands around Spokane and raised a golden horse he named Honey.

By 1967 the behavioral issues he had developed in school caught up with him. At age 17, a run-in with the law prompted a judge to give him the unenviable choice of jail or the military. He chose the marines, and could hardly have picked a more inopportune time.

Vietnam

While Beal was training for combat with the 27th Marine Division at Camp Pendleton in San Diego, the People's Army of the Republic in Vietnam was planning the massive Tet Offensive, which it launched on January 29, 1968. Beal, an 18-year-old rifleman, married Lana, then was dropped into the Vietnamese jungles in early February. His tour began at Da Nang on the South China Sea. He immediately saw intense fighting. In letters home, he described the constant bombardment of rockets and mortars, the ever-present threat of mines and hidden booby traps.

Beal was first wounded in March at Khe Sanh and suffered shrapnel wounds to both thighs, his back, right shoulder, and both hands over the coming months. These injuries would stay with him for years to come. "The doc seems to feel that I might need some mental care," he wrote in a letter. "When I was hit, we were under mortar attack. He seems to think it might have done a little something to my mind."

In July, Beal was sent to the island of Go Noi as part of Operation Allen Brook. His regiment was instructed to level a jungle lowland that became isolated when rains flooded two surrounding rivers. Artillery, air strikes, and Agent Orange devastated the landscape for days. Here he earned his nickname, "Johnny the Terror," for his hand-to-hand combat. This is also where, in August, he was taken captive, beaten, and held for 13 days in a bamboo tiger cage. He escaped with the help of a local woman and was sent to a hospital on Guam before finally returning home in September of 1968.

Returning Home

Like so many of the soldiers he served alongside, Beal struggled to acclimate to life back home. He returned to a country in which public sentiment was in full revolt against the war. He underwent surgery at a military hospital in Bremerton, then finished his contract with the marines in La Jolla, California, where his son, Robert, was born in December 1969.

During the years following his service, Beal drove trucks, repaired televisions, and installed home-security systems to support his growing family, which by 1972 had added daughter Michelle. After moving around Montana, Idaho, and Washington, they settled in Seattle in 1976. Money was tight, and the family struggled at times. Beal was never the same after the war; the horrific images, the sound of rockets, the constant fear of ambush stayed with him, bubbling to the surface as disorienting flashbacks and fits of anger.

Then, in 1979, like the father he never knew, Beal suffered a massive heart attack while combing his hair in the bathroom of his small rambler in Seattle's South Park neighborhood. He was just 29. He suffered two more heart attacks in the space of seven months, prompting two doctors to diagnose him with heart disease. "You have about four months to live," one told him, "and it's going to be a very painful death. I recommend you get a hobby."

Devastated, Beal went to a wooded area not far from home to sit and contemplate the life he had left. "It was a place no one else wanted to be and that's why I went there. I went to that place to die," he later told the Seattle P-I. A creek ran through the woods, and looking more closely he noticed the water was putrid with garbage and chemicals bleeding off an abandoned sewage-treatment plant. A half-submerged washing machine caught his eye. He dug in his heels and wrenched it from the water. With images of pock-holed Go Noi clear in his mind, Beal decided to spend his remaining days returning Hamm Creek to its natural state. "If I'm going to check out, I'm going to leave this place a little cleaner than it is now," he told The Seattle Times.

Discovering Hamm Creek

The Green-Duwamish River begins in the Cascade Mountains and winds northwest for 65 miles before draining into Elliott Bay just south of present day Seattle. The people of the Duwamish Tribe relied on the river as a transportation corridor and lived on its bounty for thousands of years. When non-Native settlers established a town on the hills between Lake Washington and Puget Sound, the river served as an important line of commercial transport for lumber and other goods. By the time Beal moved to the neighborhood of South Park, the Duwamish had largely lost its identity as a natural river, and was instead referred to as a waterway on official maps. It had become an industrial dumping ground for the paint, asphalt, boat-building, and other businesses along its degraded banks.

Hamm Creek feeds the Duwamish from the west and just happened to be a short walk from Beal's house. His work began simply and alone. He pulled old tires, cans, bags of garbage, clothing, abandoned pickup trucks, anything and everything that had been tossed away there. The more he pulled, the more emotionally invested he became. His intent grew to not only clean the creek of the garbage floating in it, but to fully restore it to the natural habitat it had once been.

Beal, who didn't finish high school and never attended college, had no formal ecological training whatsoever, but recognized that natural processes supported healthy habitats. He planted watercress, duck weed, and other native plants to restore the stream's balance, and began rehabilitating injured animals in a backyard sanctuary. He displayed his ingenuity with the Bio-Check Boom, a long boom used for oil spills that he topped with grasses and weeds to absorb toxins from the water's surface.

Building Partnerships

All this work would be in vain, though, if the hidden creek continued to serve as a dumping ground. "Industries, when they can get away with it, are going to pollute," he would say, and he turned his attention to the businesses that had to this point considered Hamm Creek or the Duwamish their private dump sites.

By most accounts, Beal was a piece of work. "With my dad, you're going to have people who love him and people who hate him," recounted his oldest child, Liana. Stubborn and bullish, he didn't care how he was received or who he irked, and his first confrontations with polluting business owners resulted in slammed doors and threats. Without an official capacity, Beal was often seen as an aggravating, if easily ignored, do-gooder. But he was not easily ignored. He persistently called out businesses that mishandled their waste and threatened legal action when they refused to stop. He reported offenders to King County and the Department of Ecology, where officials were perhaps less surprised by the ongoing pollution than they were that anyone cared enough to call. Over time, Beal recognized the need for collaboration among stakeholders and learned to establish common ground with local businesses, environmental organizations, and the Duwamish Tribe. It helped tremendously that Beal was a local -- a neighbor concerned about his neighborhood, rather than a career environmentalist only dropping in.

In 1994 he formed the nonprofit Environmental Coalition of South Seattle (now called ECOSS), capitalizing on his success helping local businesses find ways of improving their operations while protecting the watershed. The luxury-yacht builder Delta Marine, whose shipyard sits beside Hamm Creek, was one of his first successful partnerships.

I'M A PAL

The more he learned about Hamm Creek, the more problems he saw. The creek's four forks, which bleed eastward into the Duwamish, had been straightened, rerouted, and funneled through underground pipes to make way for development. Numerous studies found the entire system held unhealthy amounts of metals, including zinc, copper, and lead, and high concentrations of PCBs -- polychlorinated biphenyls -- cancer-causing chemicals once used as coolants and lubricants.

During the 1980s and 1990s, what began as a one-man cleanup project grew into a wide-scale effort, which often included his youngest son, John David, born in 1983. Beal became a beacon for other volunteers and a catalyst for the greater river-rehabilitation movement. To give himself credibility when arguing with city or county officials, and to help secure funding for projects, Beal established the I'M A PAL (International Marine Association Protecting Aquatic Life) Foundation.

Beal began work on Hamm Creek's South Fork at a spot he termed "Point Rediscovery," because it was where he initially discovered the creek's forgotten potential. He planted trees and smaller vegetation, reintroduced salmon, and cleaned up the chemical refuse of an abandoned treatment facility. After years of effort, he reestablished a small salmon population.

At the headwaters of the North Fork, rainwater pools into a soggy wetland before spilling downhill. Recognizing the ecological importance of ponds and slow-moving streams, Beal hand-placed nurse logs to create habitat -- something that occurs naturally in healthy wetlands. This restored habitat became his Outdoor Environmental Classroom, where students and at-risk youth came to learn about wetland ecosystems. Despite his prickly nature, Beal was popular with local children. He led field trips from nearby Concord Elementary School at his cleanup sites, teaching students from his pragmatic understanding of riparian ecology. The students raised salmon fry in class and brought them to the creek for release. It would not be uncommon, walking past Hamm Creek on a morning, to see Beal standing at the center of a circle of attentive school kids, pointing out salmon with one hand and chain smoking with the other.

Farther north, Hamm Creek's Lost Fork runs through Marra Farms, one of only two historically preserved farms remaining in Seattle. Beal began cleaning it up in 1997, and estimated that he cleared more than 12 tons of garbage from the site. With the help of volunteers, he also brought a section of the creek out of the ground in a process called daylighting, and helped a group of Ethiopian farmers restore the land to a productive organic farm.

Perhaps Beal's proudest achievement along the creek was the restoration of a site sandwiched between Delta Marine and an energy substation. Here, the creek's forks join and empty into the river. Seattle City Light, which owns the land, had plans to build on the site, but Beal convinced it to allow him to route the creek along its perimeter. Before the rehabilitation began in 1997, the creek crossed West Marginal Way, traveled through a small channel beside the road, and then disappeared into a pipe. By the end of 1999, Beal had daylighted the creek and established trees along its banks. The formerly piped outlet to the river was returned to a natural meander. Today, the site is vibrant with returning salmon, gliding heron, diving osprey, as well as beaver and river otter.

A Christian who believed whole-heartedly in a spiritual connection to the land, Beal instructed volunteers to name each tree they planted. A tree with a name had a better chance of growing strong, he said, and volunteers who returned years later to a restoration site could often recall their contributions by name.

Duwamish River Superfund Cleanup

Beal was introduced to the famous ocean explorer Jacques Cousteau in 1995, and the meeting left an indelible impression on him. "I learned from Jacque Cousteau that the Duwamish is part of the Ocean that we call the World," he said later. "The environment starts at your feet. You're involved in an environment every time you take a step." Beal's world following his first heart attack centered on the environment of Hamm Creek. It went to the Duwamish, and so did he.

By the mid-1990s Beal routinely patrolled the Duwamish by boat, calling in complaints to local officials, including the City of Seattle, King County, the EPA, and the Army Corps of Engineers. Most went unheeded. Government agents viewed him as a crank, and the Duwamish was still considered an industrial waterway. Local environmental organizations, however, saw his value. One of those was the Puget Soundkeeper Alliance and its executive director, BJ Cummings, who received almost weekly calls from Beal about violations.

Between 1995 and 1999, Cummings and Beal developed an effective partnership. He was her eyes and ears on the river, and she provided a legal background and trusted relationships with officials who otherwise wouldn't listen to Beal. At first he called Cummings with violations that he witnessed from his boat, which he named the Duwamish River Patrol. He and James Rasmussen, a Duwamish tribal leader and current (2018) Duwamish River Cleanup Coalition director, led volunteer kayaking clean-up crews along the river, filed complaints against polluters, and collected water samples for independent testing. Their goal was to pressure local governments to acknowledge the Duwamish as a natural river and plan for its rehabilitation. By the end of the decade, with volunteers and organizations restoring pockets of habitat along the river, there was finally enough support to push for a substantial cleanup effort. In 2001, the EPA designated the Lower Duwamish as a Superfund site, beginning a massive restoration project that was still underway in 2018.

While he was able, Beal involved himself in nearly every aspect of the cleanup, which the EPA tasked King County, the City and Port of Seattle, and the Boeing Company with managing. A group of organizations, including the Community Coalition for Environmental Justice, the Duwamish Tribe, I'M A PAL Foundation, ECOSS, Georgetown Community Council, People for Puget Sound, Puget Soundkeeper Alliance, South Park Neighborhood Association, Washington Toxics Coalition, and the Waste Action Project banded together as the Duwamish River Cleanup Coalition to serve as a watchdog overseeing the effort. As an active member of the coalition, Beal patrolled the river nearly every day. One morning in 2003 he and Cummings watched as King County's haphazard attempt to dredge the riverbed of soil contaminated with PCBs resulted only in further, and worse, contamination. That day Beal suffered another heart attack.

A Final Battle

Beal often said that his life was tied to the river. Restoring it had given him purpose through the days after his first heart attacks -- days that were supposed to be his last. Despite his diagnosis, he lived 27 more years before returning to where he had started for one final battle for the river.

In 2004 the city chose a piece of wetland at the headwaters of Hamm Creek and began illegally building an unpermitted training facility for its police officers and firefighters. Although Beal was monitoring the cleanup happening on the Duwamish, he still made weekly rounds of his restoration sites along the creek, and one day he discovered bulldozers at work. His complaints were ignored for months before the army's Corps of Engineers finally dispatched an inspector and issued a citation in 2005.

Beal lobbied exhaustively for the city to move the facility to a nearby gravel area, but Mayor Greg Nickels refused to budge. "That's what broke his heart in the end," said Rasmussen. Work continued at the site, and the facility was finished in 2007. A year after Beal's death, the city settled with the corps of engineers and agreed to $4 million of restoration work, but much of it was done along the Duwamish, not Hamm Creek. Neighbors' complaints pushed the city council to authorize more money for a study and eventual repair at the headwaters, but the study was never completed, and in 2009, amid the Great Recession, the mayor's office decided to spend the money elsewhere instead.

After battling to restore and protect the creek, Beal saw the city put a building at its source. In his final years, he suffered from diabetes, violent epileptic seizures, and other mounting health issues. His feet grew painful and he gradually lost the ability to walk. Following the defeat over the city's joint training facility, he went into a months-long depression.

Veterans Conservation Corps

Before he died, Beal had worked with State Senator Ken Jacobsen, D-Seattle, on establishing a conservation group for military veterans. Drawing from his own experience, he believed that by working to heal the environment, veterans could heal the wounds of their combat experiences. "When I came back from Vietnam, I was a wreck. I was completely broken and didn't know what to do or where to go," Beal testified before the state senate's resources committee in 2005. "I know that there are veterans right now who today have those same problems ... I think this is an opportunity for the state of Washington to start a project that will, I think, be a model for the United States."

The Veterans Conservation Corps was established by the Washington legislature in 2007. Today, across the country, corps modeled after the program Beal helped found in Washington aid thousands of veterans adapt to post-service life among their peers through hands-on involvement in natural resources. They monitor and restore streams and watersheds, plant native vegetation, restore forests, prairies, and native grasslands, and study environmental education.

Awards and Honors

By rediscovering a river that had been lost, Beal exposed the simple yet profoundly important truth that the river could be saved. This was perhaps his greatest contribution to Seattle's environmental community. His story proves that one person could undo years of harm, and he was not shy about making the fact known. Beal was a popular subject for newspapers, magazines, and books. Over the years, he was honored by mayors, congress members, environmentalists, and school children. He received numerous awards, including the United States/United Nations Environmental Programs Award, Seattle Audubon Society Environmentalist Award, King County Parks System Certificate of Appreciation, Green-Duwamish Watershed Alliance Hero Award, King County Earth Legacy Award, Environmental Law Institute National Wetlands Award, and others. He was a Reader's Digest Hero for Today, appears in the International Who's Who of Entrepreneurs, and was recognized in the John Beal Memorial Garden at Concord Elementary School. Each year, the Duwamish Alive Coalition presents the John Beal Environmental Stewardship Award in the spirit of what he exhibited.

John Beal died on June 23, 2006, at the age of 56.