Morris "Red" Badgro was a versatile athlete who grew up in the now-gone small town of Orillia in South King County, achieved multi-sport stardom at the University of Southern California (USC), briefly played major-league baseball, and became a standout end in the early days of the National Football League (NFL). Playing for the New York Giants in 1933, he scored the first touchdown in the first NFL championship game. He later became a college football coach at several schools, including the University of Washington where he spent eight years as an assistant. He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1981.

Raised in Orillia

Red Badgro was born December 1, 1902, the second of three sons of Walter H. and Cora M. Badgro. Walter Badgro was a farmer, as were most of his neighbors in the South Duwamish Valley. The community of Orillia, which was in southern Tukwila, no longer exists. But in the early 1900s, Orillia was "town" to the locals (Reinartz, 240), with two general stores, two blacksmiths, a tinsmith, a shoemaker, a butcher, a Grange Hall, a church shared by Lutherans and Episcopalians, and a two-teacher school for grades 1-10. Orillia and Renton Junction, little more than a mile to the north, were adjacent stops on the Interurban electric railway. They had a combined population of 440 in 1910 and shared Orillia's post office and school. When children from either community were ready for high school, they caught the Interurban to either north Renton or, in Badgro's case, south to Kent.

Growing up, Badgro didn't think much about the sport that would bring him the most fame. He favored baseball and basketball. At age 15, he was playing forward for the Orillia Athletic Club Grangers basketball team. He was twice captain of both the baseball and basketball teams at Kent High School. "I think I played maybe three games of football in the four years I was there" (Whittingham, 46).

Joining the Yankees

Badgro went to USC on a basketball scholarship, but talked his way onto the baseball and football teams and excelled at all three sports. One of his football teammates was a future actor -- fullback Marion Morrison, later known as John Wayne (1907-1979). In the 1926-1927 school year, Badgro made the All-Pacific-Coast football team as an end, the five-man All-Pacific-Coast basketball team as a guard, and the All-California baseball team as an outfielder after leading USC with a .352 batting average. He was due to be USC's basketball captain the following season, but was thinking about trying professional baseball instead when he ran into an unexpected opportunity in a different sport:

"I still had a couple of units to go at USC when one day I bumped into a fraternity brother of mine who had also been a starter on our football team. He was leaving the frat house with a suitcase and told me he was going out east to join Red Grange's New York Yankees. He asked me if I wanted to play pro football. I told him I hadn't really thought about it, baseball was what I had in mind. I also said I probably wouldn't mind playing it, however. Well, he said when he got to New York he would make a pitch for me ... and pretty soon I was on the train going from L.A. to New York" (Whittingham, 46).

His destination was the New York Yankees. Not to be confused with the baseball team of legendary figures Babe Ruth (1895-1948) and Lou Gehrig (1903-1941), the football Yankees were new to the NFL in 1927. They were formed one year earlier when they played in the American Football League, which folded after that single season. The football Yankees were overshadowed in New York by the more-established Giants of the NFL (who also shared a name with a major-league baseball team then still located in New York); as part of the deal allowing them in the NFL, the Yankees had to play most of their games on the road, instead of at Yankee Stadium, the field they shared with the baseball Yankees. Their main attraction was Red Grange (1903-1991), a future Hall of fame halfback nicknamed "The Galloping Ghost."

The football Yankees lasted only two seasons in the NFL. Badgro played 12 games for them in 1927 and one in 1928. By the time the team collapsed, he had moved on to professional baseball.

Reaching the Majors

A left-handed batter and right-handed outfielder, Badgro played for two minor-league teams in 1928 -- the Muskogee Chiefs of the Class C Western Association, where he posted a league-best batting average of .394, and the Tulsa Oilers of the Class A Western League, where he led the team with a .334 average. In 1929, he played 43 games for the Milwaukee Brewers of the Class AA American Association, batting .285 and earning a promotion to the American League's St. Louis Browns.

His big-league career was a short one. He hit .284 in 54 games with St. Louis in 1929, but only .239 in 89 games the following season, when his salary was $3,600. His last game with the Browns was September 18, 1930. He recalled:

"I felt if I could hit pretty well and really make it in baseball, well that would take care of it ... But I didn't hit the ball as well as I thought I would. I wasn't on the starting lineup. So after two years I decided I'd go back to football" (Whittingham, 47).

Badgro didn't quit playing pro baseball, however, toiling three more years in the minor leagues, including 1931 and 1932 with the Wichita Falls Spudders of the Texas League and a short stay in 1933 with the Seattle Indians of the Pacific Coast League. His role with the Indians had been reduced mostly to pinch-hitting, and the team cut him loose after 33 games in what was described as a cost-cutting move. Meanwhile, he was making a name for himself in the NFL.

"Murder on the Field"

In 1930, with the football Yankees gone and Badgro a free agent, the NFL Giants offered him the going rate of $150 a game to return to New York, this time to play in the Polo Grounds.

The NFL of the 1930s was a far cry from the 32-team, money-making juggernaut it became decades later. Franchises came and went, and attendance varied widely, with charity games against college stars among the biggest draws. Such exhibitions augmented the regular schedule, in extreme cases resulting in as many as four contests in an eight-day stretch. When Badgro joined the Giants, the league had 10 teams, each with only 20 to 25 players. The best ones never left the field. "Stamina played a great part in it, and the players had to pace themselves," said Wellington Mara (1916-2005), whose family owned the Giants. "They couldn't go all-out on every play, you just couldn't do that for sixty minutes of football playing time" (Whittingham, 135).

Helmets were optional, although nearly all players wore them -- tight-fitting leather ones that left their faces protruding and unprotected. Their shoulder and thigh pads were minimal, barely noticeable under their uniforms. Passes were less common than runs, which could be brutal.

"'You learned a lot about the pro game pretty quick in those days,' said center Mel Hein, [1909-1992] who joined the Giants in 1931. 'It was very rough in the line, a lot of punching and elbowing and forearms and that sort of stuff. You had to stand up for yourself or you would be walked all over'" (Whittingham, 59).

Listed as 6-feet-1 and 190 pounds, Badgro played end on both offense and defense. Steve Owen (1898-1964), a defensive lineman who also was the Giants coach, said he ''could block, tackle and catch passes equally well, and he could do each with the best of them'' (Litsky). Mara described Badgro as "a rugged, fierce competitor, and a 190-pound defensive end was pretty big in those days. He was a very mild-mannered guy, but murder on the field. ... You had to be because there were only three or four officials, and the other guy could get back at you without the officials catching on" (Litsky).

Glory Days

Badgro's Giants teammates included four other future Hall of Famers, including two from Washington -- Hein, who grew up in Bellingham and played at Washington State College, and end Ray Flaherty (1903-1994), who was born in the tiny Whitman County town of Lamont, played at Washington State and Gonzaga, and made the Hall as a coach. The others were halfback Ken Strong (1906-1979) and fullback Tuffy Leemans (1912-1979).) The Giants' chief rival was the Chicago Bears, who had their own share of football legends, including coach George Halas (1895-1983), fullback Bronko Nagurski (1908-1990), and Grange, Badgro's former teammate on the Yankees.

In 1930, Badgro's first season with the Giants, the team played for the league championship but lost to the Green Bay Packers. They did win a big victory from a league standpoint, however. In a charity game that benefitted New York's unemployed and gained credibility for the still young NFL, the Giants beat a team of former Notre Dame players coached by Knute Rockne (1888-1931) by score of 22-0 before a crowd of 55,000 at the Polo Grounds.

Badgro was named second-team All-Pro for that season, and first-team All-Pro in 1931, 1933, and 1934. His 1933 season was notable because for the first time the NFL would have an official championship game between the two division winners. Badgro caught a pass for a 15-yard gain that put the Giants in position to score the only points in a 3-0 victory over the Bears that clinched the East Division title. In the championship game, on December 17, 1933, in Chicago's Wrigley Field, Chicago was leading 6-0 when Badgro caught a pass from rookie quarterback Harry Newman (1909-2000) for a 29-yard touchdown. As the first TD in the first NFL official championship game it was an achievement that would earn Badgro a measure of fame, but the play he remembered more was the game's last one, when he was tackled by Grange just short of the goal line, preserving a 23-21 Bears victory.

Badgro's best season was 1934 when he caught a league-high 16 passes and helped the 8-5 Giants upset the undefeated Bears 30-13 in a championship game rematch. The Giants were trailing at halftime, but switched from football cleats to basketball shoes borrowed from a nearby college. With better traction on the frozen Polo Grounds turf, they dominated the rest of the way in what became known as the Sneakers Game.

In 1935, Badgro blocked a punt and returned it for the go-ahead touchdown in a victory over the Boston Redskins, but a leg injury ended his season after just five games. The Giants once again made it to the league championship game, losing to the Detroit Lions, 26-7.

Badgro left the Giants after that season to play and coach for the Syracuse Braves in a second, short-lived version of the American Football League. He played in two games and then quit because he wasn't being paid. He went back to New York City and the NFL, playing the 1936 season with the Brooklyn Dodgers, and then retired from professional football. He had played 94 games in nine NFL seasons. His totals from the five seasons for which statistics are available (1932-1936) read more like a single season's total for a receiver in the modern era: 35 catches for 560 yards and seven touchdowns.

Returning to College

His days as a professional athlete behind him, Badgro returned to USC to take courses he needed to graduate. While he was there, he coached freshmen football players. That led to coaching jobs in Ventura, California: A 1938 Associated Press story said he had signed to be head football coach at the high school there; Badgro said he coached football, baseball, and basketball at the junior college. In 1939, he accepted an offer from Columbia head coach Lou Little (1893-1979) to return to New York and coach the Lions' ends, a job he would hold for four years.

Badgro had played sports practically year-round for most of his life. Even when he was an NFL star, between seasons he played in Seattle's Commercial Basketball League. And even after the Seattle Indians released him in 1933, he didn't leave baseball, opting instead to play for Renton in the Northwest Semipro League. While at Columbia, he continued to use the time between football seasons to pursue other sports, playing in Seattle's Commercial Basketball League in the winter and working the mutuel windows at Longacres Race Track in the summer.

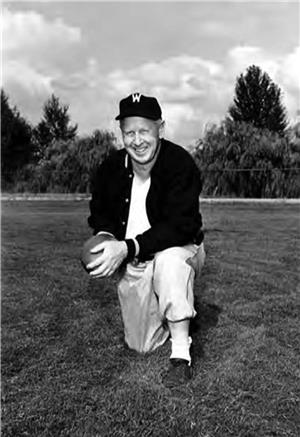

After leaving Columbia in 1942, Badgro was out of coaching until 1946 when he joined the football staff at the University of Washington. He was an assistant there for eight seasons, coaching ends and preparing scouting reports for a succession of head coaches -- Ralph Welch (1946-1947), Howie Odell (1948-1952), and Johnny Cherberg (1953). Being retained twice by incoming head coaches spoke well of his value to the team. After he died, his niece said he was recruited for head-coaching jobs, "but he wanted no part of that ... the sense of responsibility that would eliminate his individual relationships with the players" (Klass).

A Call from the Hall

Badgro retired from coaching in January 1954, leaving the Huskies to take a job as an inspector for the Department of Agriculture. He and his wife, Dorothea, lived in Kent, not far from where he was born.

Recognition of his achievements was slow to come. He was voted into the Washington Sports Hall of Fame in 1967, and was named to the All-Time Pacific Coast Conference team in 1968. As more years went by, he saw numerous former NFL teammates and opponents inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, but despite endorsements from Hein and others, he still hadn't received that honor. Not that he was one to call attention to his feats. In 1979, when a Seattle Times sports editor was preparing to write a column saying Hall of Fame recognition was due, he called the Badgro home for some career details:

"Mrs. Badgro answered. 'I never could get Badge to keep a scrapbook,' she replied, 'so I can't answer your question. And HE'S out on the golf course'" (O'Keefe, "Trojan Star ...").

Badgro was selected for the Hall of Fame in 1981 when he was 78, making him the oldest inductee up to that point and until the 2012 enshrinement of 83-year-old Jack Butler, a former cornerback for the Pittsburgh Steelers.

Badgro had been out of the NFL for 45 years when he learned he was finally deemed worthy. Asked if he thought he had been forgotten by the selection committee, he said, "I hadn't thought much about it ... All I knew was there were a lot of players who were in it who hadn't been All-Pro four times like I had. Being elected is the greatest thrill of my life. Every member of the Hall of Fame knows that thrill" (Litsky).

Enshrined at Last

The induction ceremony was held on August 1, 1981, in Canton, Ohio. Those honored along with Badgro were quarterback and placekicker George Blanda (1927-2010) of the Bears, Houston Oilers, and Oakland Raiders; center Jim Ringo (1931-2007) of the Packers; and defensive end Willie Davis (b. 1934) of the Packers and Cleveland Browns.

Hein, Badgro's former Giants teammate from Washington State, was his presenter. He described Badgro as "a very strong, 60-minute football player" ("Blanda, Davis, Ringo ...") and said, "Red built his body and his strength working on his family's farm ... He did a man's work when he was a very young boy" (Hanson). Knowing his former teammate's discomfort with public speaking, Hein added, "Now we will have Red Badgro, if he doesn't faint before he gets up here" (Hanson).

In his acceptance speech, Badgro called his induction "absolutely the greatest thrill in my life" ("Blanda, Davis, Ringo ..."), and put his NFL days in perspective:

"I received $150 a game. Now I thought that was great. I see a lot of people smiling here, but that was a lot of money -- I was glad to get it and I'm telling you it was a really great feeling because … if any of you remember the big Depression, we could buy a hot dog for five cents and a hamburger for 10 cents. I paid three dollars for a hamburger yesterday" (Hanson).

He returned home to a quiet life with Dorothea, enjoying fishing, hunting, and gardening. She died in 1993 after they had been married for 63 years. He died five years later, on July 13, 1998, after a fall at home. They are buried side by side at Hillcrest Burial Park in Kent.