In February 1884, missing the cold snap that closed the Snohomish River to steam navigation, carpenter John S. White and his family arrived in Snohomish, a small settlement on the river a dozen miles upstream from where it empties into Puget Sound and then the county seat of Snohomish County. White completed his first commission in town, building the Methodist Church, by summer of the following year. As the commissions multiplied, White was soon considered the leading contractor in the city of Snohomish, building homes for community leaders and buildings on 1st Street for their businesses. White served on the city council for three terms, and for an unknown number of years served on the school board. In 1893 he completed his own two-story brick commercial building on 1st Street and Avenue A, only to lose it several years later to the bank. John White died in 1920, after a long illness, in the home he built for his family. As with many of his noteworthy structures, the home still stood in 2018, by then occupied for more than 130 years.

A Family Affair

Born in Tamworth, New Hampshire, where he picked up the carpenter trade, White landed work in Walnut, Kansas, where he met Delia Lamb (1852-1933). They married on New Year's Day, 1871. Six years later, White's name was found in a Topeka, Kansas, business directory in a listing for "White, Holcomb & Council" as carpenters and builders.

The birth of the Whites' first daughter, Linnie, is estimated to be around this time. Alice, the second daughter, was born around 1878, and Elise in 1882, when White's name no longer appears in the Topeka business directory.

By February 1884 the family had reached the town of Snohomish, whose first non-Indian settlers had arrived some three decades earlier and which had been the county seat since Snohomish County was created in 1861 (it would lose that honor to the newer but faster-growing port city of Everett in 1897). Eight months after the family's arrival, on October 13, 1884, Snohomish County Auditor J. H. Plaskett (1842-1921) registered White's payment in the "sum of two hundred and thirteen (213) dollars" for four lots in Block One of Clay's second addition. But it would take four years for the busy contractor to build a home for his family on this property (Auditor's General Index ..., 2410).

Home and Family

The Whites moved into their new home at 310 Avenue H in 1888, the same year that the Seattle, Lake Shore & Eastern Railway arrived in Snohomish on its way north. The modest home, located in the west end of Snohomish, is a one-and-a-half story structure with a symmetrical facade punctuated by a centered side-cross gable. Measuring only 26 feet across, the facade is divided in half by the front door, gracefully announced by a simple porch, five feet deep.

Fellow Methodist Church trustee Isaac Mudgett (d. 1893) who, like White, was born in Tamworth, New Hampshire, built his own home just up the block at number 303, with the same vernacular formal features, except for a larger porch. Comparing Mudgett's simple center gable with White's decorative treatment of the gable on his home makes clear the role in his work of architectural imagination working within the common vernacular expression of the Gothic Revival style.

Linnie White, the eldest daughter, was one of the four graduates of Snohomish High School in 1896. She worked as a bookkeeper at a grocery and lived in the family home until she married Charles Sprau (1865-1940) in 1906. The couple, who had no children, moved to a fruit farm in Eastern Washington. In the 1930 census, Linnie was back at the White family home, apparently ill and under the care of her mother; she died in May of that year.

Alice, the second daughter, died of unrecorded causes at the age of 19 in 1893.

In 1902, Elise, the youngest, was living in the family home and working as an operator for the Skagit Farmers Mutual Telephone Company. Elise married Charles Roe Hooten (b. 1877) and they had one daughter, in 1912, who they named Alice, presumably after Elise's deceased sister. By 1920, the young family of three was living in Seattle, where Elise died in 1928. Her daughter, Alice, married Orin Lewis on July 2, 1932, in Port Orchard on the Kitsap Peninsula. The couple apparently had no children, and no obituary has been found for White's granddaughter Alice, topping off his family tree.

Delia White outlived her husband and all three daughters. She remained in the family home on Avenue H until her death on March 6, 1933, one year short of 50 years in Snohomish. Still a member of the Methodist Church that her husband built, Delia belonged to the Rose Rebekah Lodge, which met in the Odd Fellows Hall, also built by her husband. She was laid to rest in the I.O.O.F (Odd Fellows) Cemetery west of town (later known as Woodlawn Cemetery). All four women in the White family are interred beside each other at the highest point of the cemetery overlooking the Snohomish River, their graves surrounded by a short, gated iron fence, which was rusty and barely standing as of 2018.

Architect, Builder, and Politician

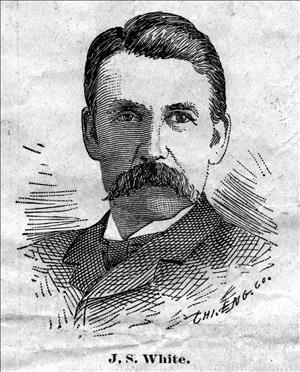

On January 1, 1891, the Weekly Sun, one of two weekly newspapers then published in Snohomish, put out a special feature of illustrated biographies titled "Our Business Men." White's 20-line bio is the most written about him during his lifetime. It includes a brief but immensely helpful list of his best-known clients at the time and vital confirmation of his role: "He is the architect and builder of nearly every building of note in the city." The biographical sketch -- accompanied by an engraved portrait that is the single rendition of his likeness known to us -- ends: "Mr. White is a fine architect, and all these buildings are after his own plans. He never charges for plans, however, where he does the building. His work is faultless, and speaks for itself" ("Our Business Men," 11).

In the summer of 1890, the settlement of Snohomish had become a city of the third class with an overwhelming vote in favor incorporation. In perhaps even bigger news, the town then also went Democratic. E. C. Ferguson (1883-1911), who had been mayor since he platted his claim in 1871, lost to businessman Hyrcanus Blackman (1847-1921), a Democrat. In fact, only two Republicans won council seats and one of them was White, who won with 222 votes, representing the west end of town. Turning 45 years old in 1890, White was having quite a year, riding a Snohomish building boom with the near completion of his three-story brick masterpiece, the Burns Block, at 1118 1st Street.

White was not re-elected to the city council in 1891 but served again in 1892, which was a troubled time for the city. The new City of Snohomish was broke due to large expenditures, including a $43,000 water system. City credit was so bad that the vendor would no longer feed the city's prisoners without cash payment. "Warrants would buy neither grub or coal," reported the city's other paper (The Eye, January 2, 1892).

It seemed to be a confusing time for White as well. His lawyer, appearing on White's behalf, made the claim in a city council meeting that the Palace Saloon encroached four inches onto his lot at 1st Street and Avenue A, and was "asking the city to remove the same," but the council was not convinced of the duty to do so, and instead instructed the city engineer to survey 1st Street from Avenues A to D and "fix the corners" (The Eye, May 4, 1892).

In August 1893 the architect's namesake White Building at 924 1st Street was occupied by "The City of Paris," a house of women's fashion, on the first floor. The oversized room on the second floor had been built out for a medical doctor. He changed his plans to open a hospital, as it was called in the press, and the room was occupied instead by the city council after its meeting place in the Bakeman Furniture Building was lost in a fire of suspicious origins that destroyed the two-year-old building.

White was again elected to the city council in 1895 and in 1896. As a city council member, he played a part in Snohomish's first reported gunfight: "Shot in Cold Blood" shouted The Eye's headline on October 31, 1895. The report went on for three columns about a midnight shooting outside the notorious Gold Leaf Saloon at the east end of town, where the owner, called "Omaha Bill," killed a patron known as "Texas Jack" ("Shot in ...").

White and his fellow council members became involved when 677 citizens petitioned them to revoke the license of the Gold Leaf Saloon. The matter was referred to a committee headed by White, which at the next meeting recommended to the full council to revoke the saloon's license. The recommendation was eventually rejected, to the vocal indignation of an active group of citizens led by the pastors in town. A rumored lawsuit did not come to pass, and an editorial in The Eye put it this way: "The council will probably not reconsider their action of 18th, and the matter will become a part of history" (The Eye, February 25, 1896).

Epilogue

On March 31, 1898, White and his wife signed a Warranty Deed selling the White Building to the First National Bank of Snohomish for one dollar. A bill of sale signed by John S. White enumerated the contents: "All of the counters, shelving and other store furniture and fixtures connected with and contain[ed] in what is known as the J. S. White Building," also for the amount of one dollar (Snohomish County Records, 391). A search of newspapers and court records revealed no further details.

J. S. White's name stopped appearing in the news by the turn of the century. ("John" was never used, and what name the "S" stands for is unknown.) Telling evidence is a five-page booster edition of the Snohomish County Tribune, published on October 21, 1898, praising the growth of the city of Snohomish, which had then reached about 3,200 in population. Page 2 features "Our Progressive People." White is not listed, nor is he mentioned in five pages of copy -- even in the list of the first councilmen elected when Snohomish approved incorporation only eight years earlier.

While White was referred to as an "architect" in the local press during his lifetime he continued to call himself a "carpenter" to the census takers. White's last will and testament, signed on March 28, 1917, three years before his death, left Delia, in addition to property and household goods, the family cow.

Structures Built by J. S. White

The following is a list of known structures built by White from 1885 through about 1910, all but the last listed in the city of Snohomish, with their status as of mid-2018.

Methodist Church, 1885: 221 Avenue B; currently occupied by a wedding-chapel business.

Odd Fellows Hall, 1866: 1205 2nd Street; White's winning bid was awarded by the members of the Snohomish Lodge 12, I.O.O.F. Sold in 1978 to a realty business, then to a private person, passed on to his heir, and currently leased to a dance school.

Getchell House, 1887: 1122 2nd Street; commissioned and occupied by Joe and Pherlissa Getchell until her passing in 1931; remained a family home until 1976 when it was divided; currently occupied as a rooming house.

Elwell House, 1888: 212 Avenue D; commissioned by lumberman Edgar Elwell, built on two lots on Avenue D near 2nd Street. Sold when Edgar and his wife, Emma, moved to the Yukon. In 1912 the new owners received an offer to purchase the southern lot from architect and builder Nels "Pete" Hansen, which included the summer kitchen of the structure built by White. Both homes are occupied as single-family residences.

Residence of Mary Low Sinclair, 1888: Featured in the August 1890 issue of The Northwest Magazine; located at 609 Pearl Street and occupied by Sinclair until her death in 1922; destroyed, date unknown.

A. M. Blackman Store, 1889: 913 1st Street; commissioned by Arthur M. Blackman, the largest grocery store in Snohomish doing both retail and wholesale, but the business failed with the 1893 national banking crash. Occupied as the Oxford Pool Hall in the early 1900s, then a tavern, and currently a saloon.

A. M. Blackman House, 1889: 330 Avenue D; features a unique design of the second floor faced with cedar shingles, a product of Blackman's cousins' mill; Arthur was living in the house when he died a widower in 1929; the unique structure continues as a single-family home.

Residence of E. C. Ferguson, 1889: Also featured in The Northwest Magazine, 1890; built so far out on the north side of town that the street had yet to be named. The large home was destroyed by fire in 1946; the Ferguson Farm next door was sold to the Snohomish School District for a junior high school; as of 2018 it is the location of the district's Snohomish Aquatic Center.

O. E. Crossman House, 1890: 329 Avenue B; Oscar Crossman's wife, Bertha, continued to live in the house following his death until 1934. The two-story home was a rooming house for many years before undergoing renovation to a single-family home by the current owners.

Burns Block, 1890: 1118 1st Street; White's, and Snohomish's, only three-story building; built of local brick as specified by the owner John Burns, a local eccentric, who built it on speculation. It has always been occupied, beginning with Horton Bros. Stationery, but is best known as the popular Schott's Meat Market of the 1940s.

Moehring House, 1891: 403 Avenue D; commissioned by Charles F. Moehring, owner of the first shoe factory and retail store of Snohomish; the business continues in Kent under a new name but still in the Moehring family, many of whom returned to Snohomish when the current owners opened the home for a 2008 Historic Home Tour featuring the structures of J. S. White.

White Building, 1893: 924 1st Street; White built his own two-story brick building on a lot he purchased from E. C. Ferguson in 1888 at the bargain price of $40 per 1st Street footage; the building features architectural brickwork unique to Snohomish; the first tenant was a women's fashion retail operation and today it is a fashionable restaurant with the original office spaces upstairs.

Bruhn & Henry Store, 1894: (unknown number on 1st Street) southeast corner of Avenue B and 1st Street, built on the site of the Bakeman Furniture Building (not built by White) destroyed by fire the previous year; Bruhn & Henry Store destroyed, date unknown.

Camp Illahee, ca. 1910: Campers Row, Clinton, Island County; White was commissioned by Ben and Nettie Morgan around 1910 to design and build a beach cabin on Whidbey Island. Thirty years later the cabin changed hands and the Chinook Jargon name "Illahee" was changed to "Drift Inn." When the extended family discussed remodeling the structure, family maternal leader Inez Bakeman reminded the three generations not to change the lines of the cabin, as it was "designed by the famous Snohomish architect, J. S. White" (Wood interview). The Drift Inn, along with other cabins on Campers Rows, was destroyed in a 2015 landslide.