On March 6, 1918, Helen Agnes Naismith (1896-1981), a University of Washington graduate, boards the troopship Celtic bound for army service in France along with the 32 other women of Unit 1, Signal Corps Female Telephone Operators. Generally called "Hello Girls," the Army Signal Corps women will operate the American Expeditionary Forces telephone system during and after World War I combat. General John J. Pershing (1860-1948), commanding the American forces, has established an American telephone system to be operated by American women telephone operators who speak French. At home women jump at the opportunity to serve. Five hundred enlist and 223 will serve overseas. The women are enlisted in the army and subject to military rules and regulations, but will be denied veteran status after the war. Signal Corps Female Telephone Operators veteran Merle Egan Anderson (1889-1986) of Seattle will lead a 50-year effort for the women to obtain military recognition and finally, in 1979, surviving World War I telephone operators will receive official honorable discharges recognizing their military service.

Women Enlist as Army Telephone Operators

Upon his arrival in France following U.S. entry into World War I, American Expeditionary Forces commander General John J. Pershing learned that the French telephone system had been severely battle-damaged. Making matters even more difficult, the French women operators were viewed by American officers as undisciplined and lacking English-language skills. World War I was the first war in which the telephone played a major role in communications. Victory would require a viable and effective telephone system. This new technology could determine battlefield success versus failure. Pershing proposed to the United States War Department that the American Expeditionary Forces build and operate its own telephone network. The general further proposed that the switchboard operators be women, noting they would perform better than men at the task and free up men for combat. The women operators would enlist in the military, serving in the Army Signal Corps under military control and discipline.

In late November 1917 Pershing's plan was approved, with the women to be enlisted as U.S. Army Signal Corps Female Telephone Operators. They would become better known as "Hello Girls." The program became an opportunity for women to serve in the military during the war. High interest arose at the University of Washington (UW) among women French majors. The first of them to enlist was Helen Agnes Naismith. On March 6, 1918, she and 32 other women army telephone operators sailed for Europe aboard the United States Army Transport Celtic.

The operators were divided into three ranks: operator, supervisor, and chief operator. The first group, departing on the Celtic, was designated Unit 1, with Chief Operator Grace Banker (1892-1960) in command. Banker served as the senior chief operator and would achieve fame during the war. She was awarded the army's Distinguished Service Medal. The medal acknowledged her exceptional performance during the battles of St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne. She was the only woman in the Signal Corps, and one of only 18 out of 16,000 eligible officers, to be recognized with this high honor.

Another Washington woman in Unit 1 was Almeria Capistran (1893-1989) from Moxee City. She was an experienced telephone operator who was fluent in French. Word of the program spread and by the end of the war in November 1918, some 7,600 women across the country had applied, 500 were accepted, and 223 served overseas. The interest at the University of Washington was intense. In May 1918, UW graduated 12 women with French majors early so they could enlist. In this group was Adele Hoppock (1898-1967) of Seattle, who enlisted along with her sister Eleanor Hoppock (1889-1968). Fortunately for historians the Hoppock sisters wrote home frequently and their letters detailing Hello Girl experiences survived. In one of Adele's early letters she wrote that she and the other West Coast women enlistees were trained at San Francisco in telephone operations. She related that they were required to buy their uniforms and accessories. The total cost was about $300 or six months' pay. Once her operator training was finished she and several others traveled by train to an East Coast port and the voyage to France.

Serving Overseas

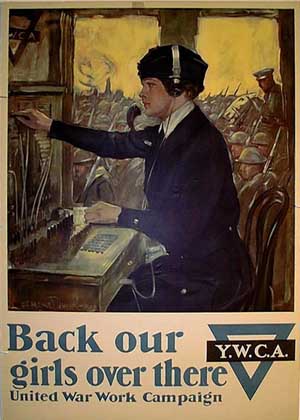

Adele Hoppock's initial duties in France were routine switchboard operations. Her overseas adventure got more exciting when she was moved to Souilly, near Verdun. Here seven operators took over an abandoned French Army barracks. The complex consisted of poorly constructed wood buildings built for the battle of Verdun. Hoppock arrived in late September 1918 as preparations for the Argonne push were underway. The Hello Girls found their building to be in deplorable condition. Old newspapers and maps were glued to the interior walls for insulation, but had little effect. Windows were oil-treated paper. However, the operators were able to improve their living conditions with the acquisition of a piano taken from an overrun German military outpost. Wherever the Hello Girls lived, they had assistance from the Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA), which helped provide curtains, furnishings, and recreational items.

At Souilly the operators were close enough to the front that they saw the glare of the shelling. When the big guns fired they could feel the ground shake. They had two switchboards, a local-and-long-distance unit and a battle switchboard called the "fighting line." When the Argonne drive was launched the "fighting lines" were busy connecting frontline units with the command center. Whenever General Pershing wished to make a call it took priority, even disconnecting other callers. The operators worked six-hour shifts, got some sleep, and then returned for another six-hour shift. Not all the operators lived in such primitive conditions as at Souilly. At rear-area locations they might live in a house or former hotel. In their limited off-duty hours they would be able to visit sights, bicycle, or hike the countryside. A number of the women chose to spend their leisure time doing volunteer work or visiting the men in American military hospitals.

Given the high ratio of men to women in the military, the telephone operators received a lot of attention. Romance was not unusual. Adele Hoppock noticed that a young first lieutenant from Seattle, Marmion Mills (1890-1964), found reason to be around the telephone compound with unexpected frequency. They would date and then marry in October 1919 upon their return to the United States. First Lieutenant Mills happened to be at the Souilly compound for one of the more memorable events there. On October 30, 1918, a fire broke out in one of the buildings. It quickly spread to the barracks building, so operators and soldiers rushed in and grabbed what they could. Moments after they pushed the piano out the door the barracks burst into flames. Then the flames threatened the switchboard building. As the fires raged the operators continued to maintain the switchboard and contact with the frontlines. Finally, they were ordered out of the building, threatened with court martial if they did not leave. Another romance found Helen Hill (1897-1982) from the Washington group dating Captain Mark W. Clark (1896-1984), although their relationship did not extend beyond the war. Mark Clark went on to to fame as a World War II general and after that war became an advocate for the operators' cause.

Adele Hoppock was in the select group of operators who served during the six-month 1919 Paris Peace conference. Her sister Eleanor also served there, as did two other Washington operators, Ellen Mildred Turner (1896-1960) and Doris Summers (1897-1981). They handled calls of the most important world leaders. Merle Egan (later Anderson) of Montana, who had arrived in Unit 5 after the Signal Corps had dropped the bilingual requirement, served as the conference chief operator. The bilingual requirement had ended in the summer of 1918, once few calls had to go through French switchboards.

At least three of the army telephone operators from UW did not go overseas. They were among the 111 waiting to ship out when the November 11, 1918, armistice ended the fighting. During the wait they had other duties. Enid Mack (1899-1979) did temporary duty in Philadelphia when a number of telephone operators fell victim to the influenza pandemic that swept the world during the war. Surprisingly, the influenza did not seriously strike the overseas Hello Girls. Marjorie McKillop (1896-1987) of Seattle was hit hard with influenza but recovered. When the war ended many overseas women telephone operators were held in Europe while other troops shipped out. The last operator left France in 1920.

Returning Home and Fighting for Justice

Of the returning wartime operators, few wanted to remain telephone operators; for most the position had been a method to serve their country during the war. Some pursued professional careers and others married and raised families. Alma Hawkins resumed teaching and had a career at Seattle's Roosevelt High School. In June 1919 Merle Egan returned to Montana and soon married Harold "Hal" R. Anderson (1877-1963). The next month Hal urged his wife to write the War Department for her Victory Medal, a medal given to all those who served in the U.S. military during World War I. She was against the idea so her husband wrote for her. The reply came back that she had not been in the army.

Several years later Merle Anderson's attitude changed. The Andersons had moved to Seattle, where Merle continued her community-service activities. In 1926, while volunteering at a hospital, she learned that the U.S. Navy had granted full benefits to female yeomen. The second-class treatment given Army Signal Corps women riled her. Merle Egan Anderson then took the lead in what became a 50-year-struggle to gain veteran status for the women who had served in the Signal Corps. Over that time period, and despite powerful advocates, more than 20 bills to do so would fail in Congress.

Adele Hoppock had returned to the United States and married Captain Marmion D. Mills on October 31, 1919, in New York City. Captain Mills remained in the army and was able to get assigned to Camp Lewis in Pierce County, near his and Adele's hometown of Seattle. He left the army in 1926 to become a transportation engineer, taking the family to Michigan. In 1938 the Mills family returned to Washington and Marmion became general manager of Seattle Transit. He led the city's conversion from streetcars to buses. In 1942, during World War II, Marmion Mills was recalled to active duty, taking command of the Mount Rainier Ordnance Depot. After he retired in 1946, the couple lived on Bainbridge Island. Both Adele and Marmion Mills wrote letters to Congress seeking recognition of the veteran status of the women who had served in the Army Signal Corps.

In 1975 Seattle attorney Mark M. Hough (b. 1945) read a Seattle Times article about Merle Anderson titled "1918 Operator Still Seeking Justice after 50 Years," and called her to offer pro bono his legal support. He recommended a new approach. Hough proposed political action followed by legal action if necessary. Hough believed that the Signal Corps telephone operators had a strong case both politically and legally. Hough and Patricia Leeper, coordinator of the National Organization of Women (NOW) task force for women in the military, put together a political presentation in support of the army telephone operators. It demonstrated that the women had been in uniform and under military discipline and control. Therefore they were members of the army and eligible for veteran status.

To support that claim, the advocates needed uniforms, paperwork, and army documents. World War I Signal Corps telephone operators provided a uniform, travel orders, and documents. These artifacts demonstrated that the Army Signal Corps treated them as members of the military just as if they were soldiers. It would require four more years to get the job done. An invitation to appear before the Senate Committee on Veterans Affairs came to Merle Egan Anderson in May 1977. Unable to attend due to health conditions, she and other veterans submitted sworn affidavits. Gertrude Hoppock (1894-1981), whose army telephone operator sisters Adele and Eleanor had both died, also provided a sworn statement. Hough and Leeper made public appearances speaking on behalf of the women World War I veterans. For the next six months pressure was maintained on the Senate committee. Success ultimately came in November 1978 when President Jimmy Carter (b. 1924) signed a veterans' bill containing provisions that made possible official discharge papers and Victory Medals for the women who had served in the Signal Corps during World War I.

Remembering the "Hello Girls"

Finally in 1979 at ceremonies across the nation the victory of achieving recognition as veterans was realized. Surviving women telephone operators in Washington were invited to Fort Lawton in Seattle to receive their official honorable discharges. On August 28, 1979, three smiling World War I telephone operators -- Merle Egan Anderson, Marjorie McKillop, and Alma Hawkins -- received their papers. Brigadier General Edward L. Trobaugh (b. 1932), assistant division commander, 9th Infantry Division, from Fort Lewis, presented the papers by which the army finally admitted the operators' legitimacy.

Several former Hello Girls donated their wartime uniforms to museums. The U.S. Army Signal Corps Museum in Augusta, Georgia, has a Hello Girls exhibit. Another military museum with an exhibit is the U.S. Army Women's Museum at Fort Lee, Virginia. Seattle attorney Mark M. Hough delivered the uniform used as evidence in the Senate hearing to the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Missouri. In the Lewis Army Museum collection at Joint Base Lewis-McChord in Pierce County is the uniform of Marie LeBlanc Drumm of Tacoma. With the belated congressional action these women could be buried with American flags on their coffins and have veterans' headstones. The headstone of Doris E. Summers Vaughan (1897-1981), a University of Washington graduate and Hello Girl, proudly records her army service as February 19, 1918, to June 30, 1919. This would have been illegal prior to 1979.