On March 8, 1900, the Seattle City Council grants a 35-year consolidated street-railway franchise to the Seattle Electric Company. This combines the city's tangle of separate streetcar and cable-car lines into one privately owned company, under the umbrella of a national utility giant. The franchise proposal has been the subject of controversy for nearly a year, with many of the city's progressives pushing for municipal rather than private ownership of the street railways. The progressives win some concessions, but the Seattle City Council eventually votes nine to three to grant the franchise. The Seattle Electric Company will evolve into Puget Sound Traction, Light & Power and eventually sell the entire system to the city in 1919 -- long before the 35-year franchise expires.

Two Options

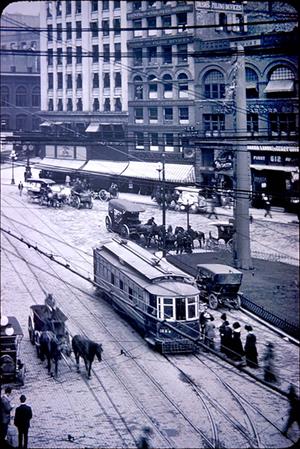

In Seattle's early transit days, streetcar and cable-car lines were owned by a confusing jumble of private companies. A passenger transferring from one line to another needed a new timetable, a new fare, and a new ticket. By 1899, the situation had come to a head. The choice, in the words of Seattle streetcar historian Leslie Blanchard, was "between consolidation and chaos" (Blanchard, 25). The city chose consolidation.

Two consolidation options were available. Seattle could consolidate the system under municipal ownership, the choice of the era's progressives. Or it could consolidate the system under the ownership of the Stone & Webster Management Company, a national utility giant that owned streetcar monopolies in many other cities. The local Stone & Webster agent, Seattle banker and streetcar entrepreneur Jacob Furth (1840-1914), offered to buy up the city's streetcar lines and create a single Stone & Webster streetcar system called the Seattle Electric Company, on the condition that the city grant Stone & Webster a 40-year franchise.

The Seattle City Council leaned toward the Stone & Webster option, partly because of Furth's proven track record of competence, and the Seattle Electric Company quickly bought up six of the city's 10 streetcar lines in anticipation of winning the franchise. A powerful backlash developed from the city's progressives, who were concerned about the dangers of a privately owned utility monopoly. A special council committee was appointed in 1899 to study the issue. Its chairman called the franchise "the biggest proposition ever handled by a special committee ... every member of the committee realizes that big interests are at stake" ("Consolidated Road").

Municipal-ownership advocates lobbied the committee furiously and, by the beginning of 1900, they had succeeded in getting several concessions. The length of the proposed franchise was reduced from 40 years to 35 years, and the company was required to allow free transfers and bulk discounted-ticket purchases. Stone & Webster promised to sink $1 million into badly needed maintenance and improvements, and to extend a number of lines.

Meeting and Vote

Nonetheless, progressives also sought a court injunction against the plan in early 1900, but were unsuccessful. The tussle over the franchise continued right up to the final vote. The council had received two bids for the franchise, one from Furth, representing Stone & Webster, and the other from a somewhat mysterious entity called Craven & Craven. At the city council meeting on March 8 at 8 p.m., the hour set for the appearance of the bidders, only Furth and his attorney were present. There was no sign of the highest bidder, Craven & Craven.

The council members duly questioned Furth about whether he had the will and financial resources to operate and maintain the city's street railways. Furth answered in the affirmative. They would have directed the same questions to Craven & Craven, if there had been anyone to direct them to.

Even though the Craven & Craven bid was highest, and seemingly more lucrative for the city, some council members declared their extreme skepticism of that bid. It had arrived in an envelope that bore the name of the law firm that had been fighting the franchise plan in the courts. One council member introduced a resolution that that called the Craven & Craven bid "not a bona fide bid, but a sham and fictitious bid" ("May Begin Work ..."). The resolution said that Craven & Craven did not have the financial backing to ever operate the franchise. It called for rejecting the Crave & Craven bid.

Several council members opposed the resolution on the grounds that the franchise should be awarded to the highest bidder. Most members of the council backed the resolution, however, which passed by a vote of nine to three. The actual franchise vote followed immediately, and it passed by the same margin.

Tumultuous Era

The vote marked the beginning of the tumultuous Stone & Webster era in Seattle. The Seattle Electric Company snapped up Seattle's remaining four lines by 1903, making the firm's Seattle streetcar monopoly complete. Almost all of Seattle's electric generating plants were included as well. The Seattle Electric Company soon evolved into the Puget Sound Traction, Light & Power Company, which would grow into a utility giant -- today's Puget Sound Energy.

Stone & Webster, however, did not hold the street railway franchise for the full 35 years that the council granted in 1900. The company did not make good on its promise to maintain and improve Seattle's street-railway system. The system deteriorated over the next two decades and an increasingly fed-up populace demanded change. In 1919, the City of Seattle bought the entire street-railway system from Puget Sound Traction, Light & Power, thus removing the word "traction" from its name. Almost two decades after the franchise-consolidation fight, municipal ownership won out after all and the Seattle Municipal Railway took over the entire streetcar system.