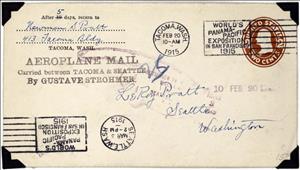

On February 20, 1915, at 10 a.m. on a chilly Saturday, a "hydroaeroplane" taxies along Tacoma's Middle Waterway. It carries its builder and pilot, Gustav Stromer; an actress named Jane O'Roark; and a bag containing several dozen letters canceled with the custom-made postmark "Aeroplane Mail." Twenty-seven minutes later, the plane and cargo land in Elliott Bay. O'Roark gets a ride to shore and another ride to the Seattle post office, where she completes the first airmail delivery between the two cities. She gets back to Tacoma, by car, in time for her matinée performance at Tacoma's Empress Theater. Both Stromer and O' Roark will leave town soon thereafter, and the promised regular airmail route will not materialize until the 1920s.

Flying for Fame

Gustav Stromer began building airplanes in Washington around 1912. (His given names also appear in the record as "Gustave" or "George W.," and the last name is sometimes spelled "Strohmer," including in the special cancelation mark on the airmail he carried, apparently a spelling error). By 1914 he had a workshop on Day Island, at the south end of the Tacoma Narrows in what is now the city of University Place. He barnstormed local events, took passengers for sightseeing spins, and promoted aviation any way he could think of. In early January 1915 Stromer met Jane O'Roark, who also had a collection of names including Emile Rorke, Emma Roark, Jane Gray, and "the Theda Bara of dramatic stock" ("Former Oakland Actress ..."). On morning of the 13th, he made her the first woman to see Tacoma from the air, an excursion undertaken to the well-publicized dismay of Charles Richards, the manager of the Empress Theater on Pacific Avenue, where O'Roark was starring that day. Despite the discomfort of an open cockpit in January with no more than a red sweater and a wool hat for warmth, she had a great time.

O'Roark and Stromer decided to fly to Seattle next, and got permission to carry the U.S. mail, including a letter from Mayor Angelo Fawcett (1846-1928) of Tacoma to his Seattle counterpart Hiram Gill (1866-1919). To increase the publicity value of the flight, they arranged for Jack Haswell, a Tacoma car dealer, to race them to Seattle in a red Maxwell speedster. On the appointed day, Saturday, February 20, 1915, the flight itself was uneventful:

"The hydroaeroplane rose through light fog, crossed Brown's Point and straightened out over East Passage, following the steamer route to Seattle. The plane caught and passed the steamer Indianapolis off Poverty Bay, skirted Three Tree Point and West Seattle in patchy fog, and prepared for a landing in Elliott Bay off Colman Dock about 10:24" (Morgan).

However, the landing was delayed by the chop kicked up by the SS Kennedy as it steamed out on the way to Victoria, B.C., and when Stromer did bring the plane down, the splash soaked him and O'Roark and killed the motor. Instead of an elegant disembarkation at Colman Dock, O'Roark and Stromer drifted for about 15 minutes before she got a ride from a passing rowboat and clambered out at Pier 1. She hitched a ride to the post office and got there just as Haswell pulled up in the Maxwell after a 46-minute sprint at close to 60 miles per hour.

A Dramatic Life

The Seattle Star described O'Roark on arrival as "blue lipped, shivering and wet to the skin, but not as peevish as one might expect of the artistic temperament" ("Actress Travels in Clouds"). After she made her delivery, Haswell drove her back to Tacoma in time for her double role in the Jack Lait (1883-1954) play Help Wanted at the Empress. She played both a stenographer who was lusted after by her wealthy employer and the roue's long-suffering wife.

O'Roark's real life had its own drama. She was in Tacoma in part to put distance between herself and a scandalous bankruptcy filing in Los Angeles. She had told the court that local businessmen had loaned her money, $30,000 in the case of one Mervin J. Monnette (1847-1931), to pay for her theater training. The loans were unsecured, and the dramatic academies evidently didn't provide receipts, so Monnette, who was at the time courting a much younger woman to be his second wife, found it expedient to not remember making any such payment. O'Roark started her Washington state sojourn at Seattle's New Washington Hotel, where she was evicted for nonpayment. (A pair of her silk pajamas were later seized as partial restitution.) She then rented a house in Tacoma, installed herself and her mother, and started driving around in the borrowed Maxwell.

Flights of Fancy

Stromer was also known for living on the edge. The previous year he had made two forced landings and then survived a crash, all while attempting to fly from Tacoma to Chehalis for a Fourth of July celebration. The Chehalis Nugget reported that several ribs were broken in the crash, not specifying whether they belonged to Stromer or his aircraft. When he did get to Chehalis on July 5, he arrived in dramatic fashion.

"[I]t appeared at first that he had wrecked his machine as when he landed in the oat field he struck some soft ground and the machine turned completely over. He was momentarily stunned, but not injured, and climbed out before anyone arrived. The injuries to his machine as a result were a broken stay and a smashed rudder. Those were repaired, however, and Stromer made his first flight Monday evening when he circled the city twice making two beautiful flights and attracting much attention" ("Gustav Stromer").

Ten days later, he wrecked his biplane on a flight from Centralia back to Tacoma, somersaulting the plane after its undercarriage caught on a wire.

"The small crowd that had turned out at the early morning hour to watch the flight ran to where the biplane lay, a mass of wreckage, expecting to find Stromer dead, but the aviator was on his feet before help arrived. After ascertaining that the machine could not be repaired on the spot, Stromer and his manager drove to Tacoma by automobile" ("Gustav Stromer").

A few weeks before the airmail flight, Stromer had announced plans to both fly and land his plane upside-down, using a second set of wheels he had installed on the top. He also petitioned to organize an aviation corps in the Washington state militia. Neither scheme is known to have been carried out.

By 1917, Stromer had moved his operation to Portland, Oregon, where he had a floating workshop on the Willamette River and began promoting a transcontinental flight. He and his flying partner T. H. Lipps were hoping to make the first coast-to-coast flight by a seaplane.

On Stage and in Court

O'Roark also left the area, returning to Southern California. She declared bankruptcy again in 1917, and was sued in 1920 for an unpaid loan of $981. She told the court the collateral she had offered for the loan from William M. Wantland was imaginary, put in the document to make the transaction look legitimate to his wife. He dropped the case, and she headed east to act in vaudeville under the name Jane Gray. In 1922 she was in the news and in court again, sued by a Philadelphia rug dealer for posing as a wealthy matron and defrauding him of $2,000 worth of rugs and by a New York apartment owner for stealing his furniture.

In 1932, by then a New York nightclub owner (or possibly a caterer), she switched sides and sued Jessie Woolworth Donahue (1886-1971), a socialite and heiress of the Woolworth dime-store fortune, for $100,000 for defamation. Donahue's husband, J. T. Donahue (1888-1931), had died by poison the previous year as his debts mounted, and O'Roark said a portion of that money had been spent on her. O'Roark's complaint stated that Jessie Donahue had said "I was a dangerous, vicious woman of unmoral and unchaste character and that no good person should speak to me" -- Donahue responded that she had said no such thing ("Mrs. Donahue Defendant ...").

Neither O'Roark nor Stromer showed up in the aviation or mail-delivery professions again. The first regular Washington-based airmail flights, between Seattle and Victoria, B.C., began in 1920 with Eddie Hubbard (1889-1928), Boeing's first test pilot, at the controls.