A common image of the Ku Klux Klan depicts robed and hooded white men in the post-Civil War South, nightriders on horseback, burning crosses and terrorizing freed black slaves and anyone who dared support them. Although mostly accurate, this is somewhat misleading. Those nineteenth-century vigilantes were merely the First Klan, and they did not burn crosses. By the mid-1870s their rampages had largely ceased, and by the beginning of the twentieth century that Klan barely existed, if at all. A half century after the Civil War a "Second Klan" came into being, and it would become the largest, most widespread, and politically powerful movement of racists, religious bigots, and nativists that the country had seen. The First Klan was confined to the Deep South, but the Second Klan penetrated all 48 states and beyond, reaching a membership of more than four million in the mid-1920s before dying out itself. Even Washington state, with a tradition of strong labor and Progressive movements, was not immune, although it proved less susceptible to Klan influence than much of the country, including Oregon.

The First Klan

The original Ku Klux Klan (KKK) was founded in 1865 in Pulaski, Tennessee. Its name was derived from the ancient Greek kyklos, or circle, and its first "Grand Wizard" was a former Confederate general and slave trader, Nathan Bedford Forrest (1821-1877). The Klan's purpose was to thwart the federal government's post-Civil War Reconstruction efforts to secure equality for more than three million freed slaves in the South. Its main tactic was terror; its hallmarks were beatings, arson, rape, and lynching.

By the early 1870s federal troops had largely suppressed the Klan, and Reconstruction continued until an unwritten political bargain, the Compromise of 1877, ended federal intervention. Southern states soon passed "Jim Crow" laws that codified segregation. In 1896 the U.S. Supreme Court upheld such laws in Plessy v. Ferguson, and it would not repudiate Plessy's "separate but equal" doctrine until the 1954 school-desegregation case Brown v. Board of Education.

The Second Klan

The Ku Klux Klan's true heyday began half a century after the Civil War, when William Joseph Simmons (1880-1945) founded what historians call the Second Klan. On Thanksgiving Day 1915 Simmons, a sometime-preacher who belonged to more than a dozen fraternal secret societies, gathered 15 like-minded brethren and chartered a bus to Stone Mountain, a huge mound of rock near Atlanta. There he put a torch to a pinewood cross "and the Ku Klux Klan of the 20th century was born" ("Ku Klux Klan: A History ...").

Simmons was inspired in large part by The Birth of a Nation, a film by D. W. Griffith (1875-1948) released the previous February. It depicts the period following the Civil War as "a time when vengeful former slaves, opportunistic white scalawags, and corrupt Yankee carpetbaggers plundered and oppressed the former Confederacy until respectable white Southerners rose up and restored order" (Mintz). The "respectable white Southerners" were the Klan, and the movie is inflammatory and shockingly racist. It is also considered a cinematic masterpiece, a three-hour, technically brilliant epic that greatly influenced the future of filmmaking. Upon release it was seen by millions of Americans, and it had a second successful theater run in 1921. The Birth of a Nation and the nostalgic passions it incited played a significant role in the spectacular growth of the Second Klan.

But that came later. Simmons, entranced by the arcana of secret societies, spent most of his time ornately embellishing the First Klan's ritualistic and linguistic bunkum. He titled himself Imperial Wizard of the Invisible Empire and wrote pamphlets for "Klankraft," including the organization's handbook, the Kloran. Local units, called "Klaverns," would be led by Grand Dragons and (invariably male) underlings -- "Hydras, Great Titans, Furies, Giant Kleagles, King Kleagles, Exalted Cyclops and Terrors" (Erickson, 1). Simmons paid little attention to recruiting, and after four years the Atlanta chapter he founded was still smaller than the local B'nai B'rith.

Selling Hate

Edward Young Clarke (1877-?) and Mary Elizabeth Tyler (1881-1924) were ahead-of-their-time hucksters whose Southern Publicity Association, a for-profit fundraising operation, had among its clients the Anti-Saloon League and the Red Cross. In June 1920 they signed up Simmons and morphed the company into a "Department of Propagation" for the Klan (Alexander, 351). They trained hundreds of recruiters -- Kleagles in Klan parlance -- and by September the most-talented were being sent off to other states.

It was, from the start, a pyramid scheme. Of each $10 membership fee, Simmons's share was $2 and Clarke and Tyler took $8, out of which the couple paid all the expenses of the campaign, including generous sales commissions. This left them with a net profit of approximately $2.50 per new member. By December 1921 more than 700,000 men had joined the Klan. While no accurate records exist, this theoretically would have enriched Clarke and Tyler by $1,750,000 -- considerably more than $20 million in 2019 dollars -- and Simmons by not much less. Additional profit came from the sale of necessary Klan regalia, including robes and hoods that cost $6 each.

With so much money at stake, internal battles were inevitable. At the "Imperial Klonvocation" in Atlanta in August 1922, founder Simmons was kicked upstairs, given the title of "Imperial Emperor," but stripped of operational control (Jackson, 360). Clarke and Tyler were forced out in 1923, but the train rolled on without them. By 1925 the Second Klan had more than four million members, and the true count was probably higher (it was, after all, a "secret" society). It had become very big business indeed, a fact that would before long contribute to its equally rapid decline.

A Klan for Its Time

There was more to the Second Klan's nationwide success than just good salesmanship. Between 1910 and 1930 nearly a million black Southerners moved north, with most settling in major industrial cities. Many white Northerners who supported equal rights in principle were less keen to find African Americans living in their cities and competing for jobs. Large numbers of immigrants from Europe, including many Catholics and Jews, were additional irritants to some.

The Klan skillfully played on the rising tensions, demonizing not only blacks and immigrants, but also Asian Americans, Mexican Americans, Catholics, Jews, the unemployed -- just about everyone and everything that wasn't white, native-born, God-fearing, Protestant, and hyper-patriotic. The Klan also railed against immorality in all its forms, and supported aggressive enforcement of Prohibition. Its recruiting pitch was sophisticated and chameleon-like -- "anti-Japanese in the Pacific states, anti-Semitic in the Atlantic states, and anti-Mexican in the Southwest. The Klan offered a target for every frustration" (Schaefer, 147).

Changing Times

When Washington Territory was created in 1853 it was slave-free. Four years later the federal law that mandated that status, the Missouri Compromise of 1820, was ruled unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in the odious Dred Scott decision. This had no practical effect in Washington, where the 1860 federal census counted only 30 "Coloreds." Unlike the intensively agricultural South, there was no economic excuse for slave labor in the Northwest, regardless of opinions about its morality. Washington Territory also remained largely untouched by the Civil War and was unsullied by the Reconstruction-era Klan.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century a number of reform groups coalesced in the state. The Progressive Movement united rural Washingtonians, represented by the Grange and the Farmers Union, with urban progressives and organized labor to form a potent political force. In 1910 voters passed a state constitutional amendment mandating woman suffrage, a decade before it became law nationwide. In 1911 the Public Ports Act ended private monopoly control of the state's urban harbors. In 1912 voters approved a constitutional amendment giving citizens the rights of initiative, referendum, and recall. In 1914, they exercised their right of initiative for the first time to enact a state ban on the manufacture and sale of alcohol, six years before Prohibition was imposed nationally. The successes and thrust of the Progressive Movement should have made Washington a hard sell for a hate group like the Klan.

That would change. By 1920 the state had fewer than 7,000 African Americans, but more than 17,000 Japanese residents. In the years leading up to the start of World War I in 1914, more than a million immigrants entered the country annually, many from southern and eastern Europe, ethnically diverse, impoverished, often illiterate and speaking little or no English. Immigration slowed during the war, but rebounded in its wake, boosted by refugees fleeing post-war tumult and economic collapse. By 1920 more than a quarter-million foreign-born people lived in the state, nearly 20 percent of the total. Among them were numbers of Catholics and Jews, favorite targets, along with blacks and Japanese, of the Second Klan. The war itself had stimulated anti-foreign sentiment, and this only increased as immigrants competed with native-born Americans for jobs. The Klan and other nativist groups skillfully played on public fear of "the Other."

The Bolshevist takeover in Russia in late 1917 triggered concerns about a Communist world revolution. Seattle's General Strike, which started on February 6, 1919, and was the first such coordinated labor action in the nation's history, exacerbated those fears. Widely seen as instigated by leftist radicals, the strike quickly failed, but it fractured the labor movement and drove a wedge between it and its former allies. Then, in 1921, the state legislature, with significant support from labor, passed the blatantly racist Alien Land Bill, which prohibited non-white immigrants from buying, owning, or leasing land in Washington.

Although the Klan's core belief in white supremacy, at least vis-a-vis black Americans, probably had relatively little resonance here, by 1921 there was a ready audience for much of its agenda -- antipathy to unions, liberals, leftists, and the unemployed; anti-immigrant xenophobia; hostility to perceived elites; dedication to conservative family values; fierce religious bigotry; and the embrace of a fundamentalist strain of Protestant Christianity. Washington's door was ajar, and the Second Klan's recruiters were ready to step in.

The Klan Moves North

One of the first reports in a Seattle newspaper of the resurgent Klan appeared in The Seattle Times on July 14, 1918, headlined "Ku Klux Klan Again Gets Busy in the South." In November 1920 the paper reported that the Klan was planning to open a branch in New York City, and the following month The Seattle Star carried a picture of Klan founder Simmons and reported his claim that "the organization is growing rapidly, and requests for local chapters are coming from all parts of the nation" ("Ku Klux Klan Growing"). Clarke and Tyler's Department of Propagation was in full swing, and an August 4, 1921, report in the Star claimed the Klan already had five groups "operating in the city of Tacoma and others in Kent, Auburn and adjacent communities" ("Ku Klux Klan Organizes ..."). Three weeks later, The Seattle Times ran an anti-Klan editorial, but without mentioning any local Klan activity.

Then, on September 6, 1921, the Times printed the first installment of a multi-part investigative exposé of the Klan compiled by The New York World. Two days later the Seattle paper gleefully announced that "The Seattle Times and The New York World, together with a number of other newspapers of the country, are honored by being threatened by the Ku Klux Klan" ("Times Threatened ..."). One week after that, on its front page, the paper identified G. L. Williams of Atlanta as the "King Kleagle" of "the Invisible Empire of the Ku Klux Klan" for the "Realm of Washington" -- he had arrived quietly the previous June to start recruiting, and claimed to have had "wonderful success" ("Seattle Ku Klux Klan!"). Far from invisible, Williams posed for a photograph that, remarkably for a newspaper of that time, was printed in color.

Ironically, the World's exposé seemed to have the opposite effect of what was intended: "Historians of the Klan of the 1920s agree, with remarkable unanimity across nearly a century's writing, that a cause-and-effect relationship exists between the World's exposé and the Klan's later prominence" (Kneebone, 1).

Luther Ivan Powell

Within a month of his public unveiling, Williams stepped down after threats from other Klan factions, probably having to do with money. He was replaced by L. M. McFarlin of Shreveport, Louisiana, who opened a temporary office in the St. Regis Hotel on Seattle's Stewart Street. McFarlin's tenure as top man ended with the arrival of "Major" Luther Ivan Powell (1878-1951), a bright star in the Klan's recruiting firmament.

Powell, also a native of Louisiana and an early graduate of the Klan's Department of Propagation, was first dispatched to California, where he polished his skills recruiting members up and down the state before crossing the border into Medford, Oregon, in the spring of 1921. That state proved unusually receptive to the Second Klan's appeal and to the spiel of a salesman of Powell's skill. Oregon (unlike Washington) had a legacy of anti-black legislation dating back to territorial days, but Powell studied his audience and calibrated his pitch to stress the Klan's support for Prohibition and opposition to Catholicism. Other secret societies, including the Odd Fellows, Knights of Columbus, and Freemasons, proved fertile fields for recruitment.

Powell soon was appointed King Kleagle for Oregon, and he established Klan chapters in Medford, Klamath Falls, and Roseburg before setting his sights on Portland in February 1922. Along the way he trained dozens of additional recruiters and sent them across the state, taking a cut from each new initiation fee. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center's Klanwatch Project, "Incredibly, within a year of the arrival of a single Klan salesman [Powell], Oregon was so firmly in the grasp of the hooded nightriders that the governor admitted they controlled the state" ("Ku Klux Klan: A History ...").

In the November 1922 elections, Klansmen won local, county, and state offices (including state legislative seats) in Oregon, and Democrat Walter M. Pierce (1861-1954) was elected governor with Klan support. Perhaps most startling was something unique to Oregon -- in that same election, voters approved a Klan-backed initiative measure that required all children 8 to 16 years of age to attend public schools. It was a direct attack on Catholic education, but broad enough to affect other private and parochial schools as well. Three years later the U.S. Supreme Court declared the law unconstitutional.

On to Washington

Another of the Second Klan's endless internal battles had forced Powell out of Oregon earlier in 1922, but he simply crossed the Columbia River into Washington. It is probable that he established Washington's official Klavern No. 1, called the Columbia River Klan, in Vancouver late that year. He then opened an office in Seattle's Eitel Building (later moving to the Securities Building) as "King Kleagle of the Pacific Northwest Domain," which he defined as "Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Alaska and the Hawaiian Islands" ("New Anti-Klan Bill ...").

Washington would prove less susceptible than Oregon to the Second Klan's dark allure, but was by no means immune. Even before Powell's arrival, the Klan was active in Seattle and other places. On April 2, 1922, Seattle's corporate counsel was forced to deny publicly that he was a Klansman, and that same day 50 robed and hooded Klan members showed up at the city's First Presbyterian Church to hear progressive minister Mark Matthews give a sermon on "The Crime Wave Producers" ("Ku Klux Klansmen Go ...").

Powell again targeted, and taught his subordinates to target, members of other fraternal secret societies in the hunt for likely recruits. In November 1922, shortly after his arrival in Seattle, he confirmed the Klan would start ladies' auxiliaries around the state. In June 1923 he issued the first edition of The Watcher on the Tower, a weekly Klan paper that spread the word and, at 10 cents a copy, brought him additional income.

Counting Klaverns and Klansmen

Most tallies of Klaverns and membership are by necessity based on Klan claims and highly suspect, and when the Klan imploded in the later 1920s most records were destroyed or simply disappeared. An interactive map created by Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU), using information from published sources, found that in Washington, Klaverns 2, 3, 4, and 5 existed in Buckley, Walla Walla, Seattle, and Colfax, respectively, by mid-1923. VCU could positively document only 17 Klaverns in the state, but acknowledged that the count was certainly incomplete. The Klan's system of giving each local group a number marking its place in the chronology of formation indicated that there were 59. Another source puts the total at 42 ("The Battle of Wapato"). At this point, even rough quantification seems impossible.

The group's paid-up membership is no easier to pin down, although estimates put the maximum in Washington at 40,000. Contemporary accounts are of little use -- the Klan exaggerated the number of attendees at its rallies, while its opponents did the opposite. Most newspapers were anti-Klan, and many refused to cover Klan rallies at all, but a few suggestive numbers can be gleaned.

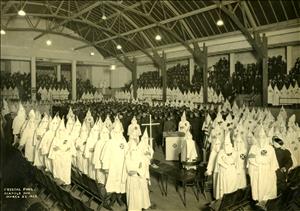

Controversy over Japanese Americans leasing land on the Yakama Indian Reservation (seen as an attempt to circumvent the Alien Land Bill) sparked four Klan rallies in the Yakima Valley in March 1923 -- at Wapato, Toppenish, Yakima, and Sunnyside -- that collectively drew several thousand people. The Klan claimed 50,000 attended its first "Konvention" in Washington, held on July 14, 1923, at Wilson's Stadium near Renton Junction south of Seattle; others counted closer to 20,000, and The Seattle Times didn't cover it at all. In Issaquah the following summer, a conservative estimate placed 13,000 participants and spectators at a Klan rally and initiation ceremony, and there were "at least a dozen smaller rallies and parades that drew hundreds and sometimes thousands of spectators around the state from 1923 to 1926" ("KKK Super Rallies ..."). And on August 9, 1924, "amidst three (electric) burning crosses and fireworks, Klan activity in Central Washington culminated ... in a field south of Yakima. Seven hundred initiates marched with 1,000 robed members before an estimated 40,000 spectators" ("The Battle of Wapato").

As those last numbers indicate, the great majority of attendees at these spectacles were not Klan members, or necessarily sympathizers. There was a dearth of public entertainment in the 1920s in small towns and rural areas. Klan rallies had "pageantry, fireworks, singing, 21 gun salutes, patriotic reenactments of events from American history, and religious sermons" ("KKK Super Rallies ..."). Nonetheless, "the massive attendance ... also demonstrated the everyday quality of white supremacy and Christian nationalism in the Pacific Northwest [and] showed that the politics of intolerance could be made remarkably palatable by simply dressing it up as a form of entertainment" ("KKK Super Rallies ...").

By Their Works Shall Ye Know Them

Some comfort may be taken from the Second Klan's inability to corrupt Washington's politics to the extent it had in several other northern states, notably Oregon and Indiana. Relatively few Klan members, or those strongly suspected of membership, were elected to public office -- one source identifies only the mayors of Kent and Blaine, Bellingham's city attorney, and Wapato's director of schools, but notes "it is likely that many other local elected officials in Washington state were Klan members" ("Citizen Klan"). The only Washington congressman seriously tainted by Klan connections and support (although membership was never established) was editor, eugenics advocate, and anti-immigration zealot Albert Johnson (1869-1957), a Republican who represented Southwest Washington's Third Congressional District from 1915 to 1933.

Nonetheless, the Klan did score some political wins. During the 1923 legislative session in Olympia, an anti-Klan bill that would have banned wearing hoods or masks in public did not make it to a final vote and was never revived. In 1924 the Klan-influenced Washington delegates to the Democratic Party's nominating convention (and those from Oregon and Idaho) unanimously opposed a plank in the platform condemning Klan violence. They also helped tear the party to shreds in a raucous and successful effort to prevent the presidential nomination of New York Governor Al Smith (1873-1944), a Roman Catholic who opposed Prohibition. This may have been the Klan's political high-water mark in the state; later that year came an election result that marked the beginning of its end.

Fade Out

In January 1924 a Klan-affiliated group announced its intent to place on the November ballot an initiative modeled on the anti-Catholic-school measure passed in Oregon in 1922. Sufficient signatures were gathered, and Initiative 49 went to Washington voters on November 4. It was soundly rejected, with more than 58 percent voting no.

To a remarkable degree, this loss took the wind out of the Klan's sails in the state, but there were other factors as well. Luther Powell had left Washington the previous fall, and his charisma and influence were sorely missed. His weekly, The Watcher on the Tower, started reprinting old articles, then stopped publishing entirely. And, as in almost every other state, the Klan's vaunted fraternal bonds were increasingly sundered by vicious internal battles.

The rapid demise of the Klan was a nationwide phenomenon, and a major cause was foretold years earlier. In August 1921 the head of its North Carolina domain, Grand Dragon Bruce Craven, disbanded his group, charging that the Klan was "nothing more than 'an organization engaged exclusively in collecting initiation fees under false pretenses' and was, in his opinion, 'a failure and a fraud'" ("Ku Klux Klan Head ...").

By 1925 many who had been drawn by the Klan's promises of brotherhood were dismayed by its hypocrisy. It was widely accepted that many Klan leaders had enriched themselves with organization funds, a situation deeply troubling to a membership attracted in large part by the vaunted moral superiority of the Klan. Another heavy blow came in October that year, when D. C. Stephenson (1891-1966), the Grand Dragon of the powerful Indiana Klan, was convicted of the rape and murder of a young woman.

The march of history also was not helpful. The Klan's apocalyptic vision of an America overtaken by racial minorities, Communists, immigrants, and immorality proved illusory. In the middle years of the 1920s the economy rebounded, labor activism ebbed, the Northern industrial cities absorbed the Great Migration with only rare unrest, laws were passed limiting immigration, and the relaxed morals of the Jazz Age did not lead to national collapse. White, native-born Protestants held on to their political and economic power. Much of the Klan's raison d'etre was simply overtaken and belied by reality.

By 1930 national Klan membership had dropped below 50,000. In Washington, Klaverns in Skagit and Whatcom counties held out until the 1930s, and one (perhaps not official) was active in Seattle as late as 1937. A number of former Washington Klansmen (including Luther Powell) joined the Silver Shirts, a white-supremacist, anti-Semitic, Christian millennialist organization founded in 1933. The national Klan organization ceased to exist in 1944 when it could no longer pay its taxes.

Nearly Forgotten, But Not Gone

In the 1960s a Third Klan arose in reaction to the civil rights movement, but did not spread widely beyond the South. The very name "Ku Klux Klan" today may seem anachronistic, a vestige of more credulous times. Nonetheless, in 2017 the Southern Poverty Law Center counted two active Klan groups in Washington, one in Spokane and one in Vancouver.

More troubling is the unavoidable fact that racism, nativism, and religious bigotry have proven seemingly ineradicable, and not only in America. In settled times these dark impulses may remain for the most part below the surface of daily life, for years, even decades. But history has shown, time and again, that when economic and demographic circumstances cause uncertainty and fear, there are those willing to play on the uncertainties and stoke the fears for political, ideological, and/or financial gain.