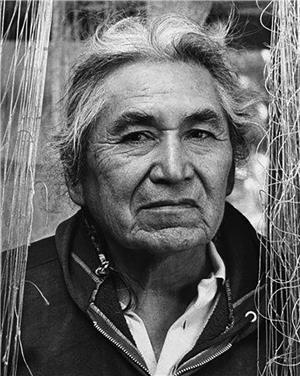

U.S. Army veteran David Sohappy Sr. (1925-1991) was a Wanapum fishing activist who became the center of a national controversy involving government regulators and tribal fishers in the Pacific Northwest. Raised by a community that relied on fishing for salmon and steelhead as a key component of its spiritual and economic livelihood, Sohappy defied fishing regulations enacted by the states of Washington and Oregon and brought public attention to the issue of treaty violations. His quiet heroism in resisting the law attracted the support of politicians and helped to clarify the treaty fishing rights of Native Americans that were being threatened both by state governments and non-Native fishing groups.

The livelihoods of Indian fishermen in Washington had been threatened long before Sohappy's story began. The rise of hydroelectric power in the first half of the twentieth century led to construction of dams that destroyed Native fishing sites and disrupted salmon migrations. And even before the dams were built, fisheries resources were being depleted by commercial fishing operations. Fish wheels containing buckets much like Ferris wheels were operated by non-Indians in the same spots where Native Americans had erected scaffolds and manipulated dip nets. Tribal fishermen, however, bore the brunt of blame for violating conservation laws. Tribal fishing rights were poorly defined, offering Indians little protection from mistreatment by the state.

Growing Up Wanapum

David Sohappy, whose surname is an anglicized form of "souihappie," meaning "shoving something under a ledge" in the Sahaptin language, was born on April 25, 1925 (Ulrich). His band, Wanapum, was never formally recognized by the U.S. government. Sohappy grew up fishing on the Columbia River in Central Washington. During his first six years, he spent spring, summer, and fall in a riverside farming town called White Bluffs. There his paternal grandmother had a salmon-curing shack. David learned his later occupation of fishing by riding in canoes with others, helping to paddle the pre-dam river, bracing as his father speared big salmon and towed them back to shore. White Bluffs is now a ghost town, its people evacuated when the Hanford Nuclear Reservation was constructed during World War II.

At 6 years old, David went to live on his maternal grandmother's farm in the Yakima Valley. He dug roots under her guidance and attended longhouse ceremonies. He started school at 7 and attended for only two years, completing the third grade. In his community he was taught the ancestral Washat (or Seven Drum) religion and the Sahaptin language. The Washat religion instilled within him the abiding belief that "the only thing the white man can teach you is how to read and write ... after that, they will try to change your mind to his way of thinking" (Conford and Zaccheo).

As a youth David met his future wife, Myra, at the longhouse ceremonies their families attended. Both families, uprooted from traditional Wanapum grounds on the Columbia River, chose to relocate to the Yakama Reservation. David and Myra married in 1945.

David Sohappy began working as a mechanic that same year, but he was drafted into the Army Air Corps in 1946. He served for 11 months and 10 days, stationed in California, Hawaii, Washington, and Virginia. He advanced to sergeant before being discharged. After returning to the farm where he had come of age, Sohappy worked variously as a farmer, carpenter, electrician, plumber, heavy-equipment driver, and sawmill operator. A fast learner, he picked up these skills on the job without the benefit of formal training.

Sustaining a Family

Sohappy lived up to his Sahaptin name, Tucknashut, meaning "provider," by fishing to sustain his family and community. When he was not working at the sawmill, Sohappy caught salmon for one or two months of every year during fishing season along the Columbia River. Salmon served many purposes for the Wanapum people. It fed their families, allowed them to barter, earned them money, and contributed to ceremonies.

The Wanapum way of life relied on fishing as a main source of sustenance, but the salmon runs on the Columbia River also intertwined with the Native religion. The arrival of the salmon each spring was celebrated with a sacred ceremony and a feast. The salmon served a function that could be seen as roughly equivalent to the Eucharist for Christians.

When Sohappy was laid off from his job at the sawmill in the mid 1960s, he decided to relocate his family so that he could rely wholly on salmon fishing to make a living. The Sohappys moved to a site in the Columbia River Gorge called Cook's Landing, in Skamania County at the mouth of the Little White Salmon River. Myra dried, smoked, and canned the fish that David and the family caught. David and Myra raised a family of eight children and many more grandchildren.

The Sohappys believed that as long as they took only as many fish as needed to support their family and community, the river would continue to provide enough salmon and steelhead for everyone. (Elsewhere in the Columbia ecosystem, "salmon chiefs" made sure fish were released as brood stock and divided the remainder equally between all tribal members gathered at traditional fishing sites.) Indifferent to the regulations set by state and tribal governments, the Sohappys followed the law of their faith, feeding family and supporting community from their modest wood-plank home at Cook's Landing for several years before David was first prosecuted for overfishing.

Police had been confiscating the fish and equipment of tribal fishermen in an effort to enforce state regulations for many years before the Sohappys arrived at Cook's Landing. As the courts would later conclude, such confiscations violated the treaties made in the 1850s between the United States and the Indian tribes of the Pacific Northwest, which protected the rights of the tribes to take "fish at usual and accustomed grounds and stations" (Harmon, 230). Even if Sohappy was not familiar with the precise language of the treaty, he followed sustainable harvest patterns his family had practiced for generations.

Challenging State Laws

In 1968, Oregon officials arrested Sohappy and his relative Richard Sohappy for gillnetting on the Columbia. That same year the Sohappys and 12 other Wanapum people, represented by University of Washington law professor Ralph Johnson and others, filed the case Sohappy v. Smith against the Oregon Fish Commission, challenging the state's violation of tribal fishing rights set by the 1855 Yakama Treaty between area tribes and the United States government. Richard Sohappy was the named plaintiff and the named defendant was Oregon fish commissioner McKee Smith. A major goal of the lawsuit was to clarify and solidify fair fishing seasons for tribal fishermen in accordance with the treaty.

David Sohappy was following in the footsteps of his direct ancestor, the prophet Smoholla (ca. 1815-1895), founder of the Washat or Seven Drum religion. Smoholla foretold the arrival of white colonizers who would destroy the traditional ways of the Indian tribes. Smoholla challenged regulations that forced Native peoples to abandon the hunting and gathering that were so integral to their traditional way of life, especially those laws that required them to take up agriculture on government-designated reservations.

Smoholla, flourishing in the mid nineteenth century, said in a famous statement, "You ask me to plow the ground. Shall I take a knife and tear my mother's bosom? Then when I die, she will not take me to her bosom to rest" (Wilkinson, Blood Struggle, 49). Smoholla taught his people that the way to protect themselves from the oppression that accompanied colonization was to follow their traditions and stand up for their way of life. That was one of the key objectives of Sohappy and the others in the Sohappy v. Smith lawsuit.

Although the Yakama Nation did not initially support Sohappy's case, due to the fact that he had been violating both state and tribal fishing regulations, key members of the Yakama Tribal Council viewed the case as a opportunity to set a precedent for the Native American fishing communities that so desperately needed their rights clarified. With the help of several other tribes, the Yakama Tribal Council lobbied to involve the U.S. government in the legal battle, hoping to strengthen the tribes' position and clarify their fishing rights and privileges once and for all. As a consequence, the U.S. government sided with the tribes and filed U.S. v. Oregon, which was consolidated with Sohappy v. Smith.

In 1969, U.S. District Court Judge Robert Belloni (1919-1999) ruled in the consolidated case that tribal fisherman should be allowed to continue catching fish along the Columbia River as they always had. Belloni also helped define the ways that states could control tribal fishing by ruling they could regulate only to an extent that might be proven to safeguard natural resources. His ruling mandated, moreover, that state governments must adjust regulations so that tribal fishers could receive a "fair and equitable share" of the salmon runs (322 F.Supp at 907-08). This meant that runs must not be obstructed or diminished before they reached tribal sites. Although the judge ruled in favor of the tribes, the fight between Native and non-Native fishermen was far from over.

Fighting at the Federal Level

By the 1970s, Native American fishers on both sides of the Cascades were being beaten, arrested, and jailed for flouting laws they perceived as violating treaty rights. At the same time, runs of salmon in the Columbia River were proving to be less bountiful than historically, thereby deepening antagonism. Restraining orders were being issued to halt all Indian fishing on the river until it could be regulated in a way that satisfied the states.

On February 12, 1974, U.S. District Court Judge George Boldt (1903-1984) shocked many and gratified Native Americans when he handed down his 203-page decision in United States v. Washington, which built upon and clarified Belloni's 1969 ruling. Boldt defined the "fair share" to which treaty-right fishers were entitled as half of the harvestable yearly fish catch (Harrison).

That ruling, known as the Boldt Decision, infuriated many non-tribal fishers, both commercial and sport. Shots were fired; Natives were beaten. In 1982, Sohappy and his son, David Sohappy Jr., were among an ultimate total of 75 people arrested for selling fish caught in violation of law. The arrests were part of a federally executed sting operation known as Salmon Scam conducted in response to dwindling salmon populations.

In 1983, the Sohappys were sentenced to five years in prison for illegal fishing. As David Sohappy Sr. was transferred to prisons in Oklahoma, Minnesota, and Washington state over the next three years, his health deteriorated and he suffered an incapacitating stroke. The head of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, Daniel Inouye of Hawaii (1924-2012), intervened in an attempt to put an end to what he saw as the Sohappys' unfair treatment. In March 1988 Inouye traveled from his home state to meet with the Sohappys in the Geiger Corrections Center in Spokane, gathered information, and subsequently pressured the federal government to release them. All four senators from Oregon and Washington likewise supported their release. Two months later, on May 18, the government granted the release of both father and son on parole. Even after David Sohappy Sr. was allowed to return to his family, however, his grievances against the U.S. government continued.

For several years before Sohappy's release, the Bureau of Indian Affairs had been trying to evict the residents of Cook's Landing. The government argued that Cook's Landing was an "in-lieu" fishing site established originally not as a place to live but instead as a river-access and boat-launch site. The Native American residents, the government said, were squatters. Truckloads of federal agents besieged the Sohappys and others at their home at Cook's Landing and portrayed them as criminals in the press.

Cementing a Legacy

The case was finally resolved in 1991 in favor of the Sohappys, their extended family, and their friends at Cook's Landing. David Sohappy Sr., however, did not live to see or celebrate the legal victory. Five months before the resolution was handed down, he died on May 6, 1991, at the Hood River Care Center, due to health problems brought on by his time in prison and his disabling stroke. He was 66 years old.

The concern fueling the Salmon Scam prosecution, that Native fishers were responsible for loss of returning salmon, turned out to have been based on exaggerated or false information. The decline in the salmon population at Cook's Landing, instead of being due directly to overfishing, was traceable in part to pollution from an aluminum plant that diverted migrating fish to tributaries away from their usual routes. Rather than addressing non-Indigenous causes of the shrinking salmon population, federal officials attempted to place sole responsibility on the Native people.

Considered a criminal in his time by officials in Oregon and Washington, and also by many members of the commercial and sport-fishing communities, David Sohappy is widely regarded today as a civil-rights activist who sacrificed his personal welfare for the greater good. His legacy has had a lasting impact both symbolically and legally. He brought renewed attention to Smoholla's warnings about the threats white colonialism posed.

The shift from traditional to commercial fishing practices, along with industrial development on and near the Columbia River, caused the various species of salmon to die back significantly. David Sohappy's confrontation of the injustice perpetrated on his people helped provide future generations of Native fishers the freedom to fish to the extent they need, very much as their ancestors did, now under the security of federal law.